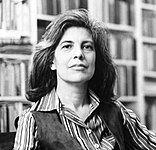

Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag was born in New York City, New York, United States on January 16th, 1933 and is the Novelist. At the age of 71, Susan Sontag biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 71 years old, Susan Sontag physical status not available right now. We will update Susan Sontag's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Susan Sontag (January 16, 1933-2004) was an American writer, filmmaker, philosopher, and political activist.

She mainly wrote essays, but also published books; in 1964, she released her first major work, "Notes on 'Camp'," an essay.

On Photography, Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, The Way We Live Now, Illness as Metaphor, Concerning the Pain of Others, The Volcano Lover, and In America are some of her best-known paintings. Sontag was involved in writing and visiting war zones, including during the Vietnam War and Sarajevo's Siege.

She wrote extensively on photography, culture, and television, HIV and AIDS, human rights, and communism and leftist ideology.

Despite the fact that her books and speeches occasionally drew criticism, she has been described as "one of the most influential critics of her generation."

Early life and education

Susan Rosenblatt was born in New York City, the daughter of Mildred (née Jacobson) and Jack Rosenblatt, both Jews of Lithuanian and Polish descent. When Susan was five years old, her father owned a fur trade company in China, where he died of tuberculosis in 1939. Sontag's mother married U.S. Army captain Nathan Sontag seven years later. Susan and her sister, Judith, adopted their stepfather's name, but he didn't adopt them formally. Sontag did not have a religious upbringing and said she had not entered a synagogue until her mid-twenties.

Sontag grew up in Long Island, New York, Arizona, then to Tucson, Arizona, and then in southern California, where she took refuge in books and graduated from North Hollywood High School at the age of 15. She began her undergraduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley, but she moved to the University of Chicago in honor of the University's renowned core curriculum. She undertook studies in philosophy, ancient history, and literature alongside her other academic interests at Chicago. Leo Strauss, Joseph Schwab, Christian Mackauer, Richard McKeon, Richard McKeon, Peter von Blanckenhagen, and Kenneth Burke were among her lecturers. She earned an A.B. at the age of 18. Phi Beta Kappa was granted to the university of Phi Beta Kappa. She made her best friends with fellow student Mike Nichols while in Chicago. For the first time in the Chicago Review's winter issue, her work appeared in print.

After a 10-day courtship, Sontag married writer Philip Rieff, a sociology professor at the University of Chicago, at 17 years old; their marriage lasted eight years. Sontag attended a summer school taught by sociologist Hans Heinrich Gerth who became a mentor and later inspired her study of German thinkers while studying in Chicago. Sontag taught freshman English at the University of Connecticut from 1952-53 academic year. She attended Harvard University for graduate school, first reading literature with Perry Miller and Harry Levin before embarking on philosophy and theology under Paul Tillich, Jacob Taubes, Raphael Demos, and Morton White. She began doctoral studies into metaphysics, ethics, Greek philosophy, and Continental philosophy and theology at Harvard after completing her Master of Arts degree in philosophy. Herbert Marcuse wrote for a year for Sontag and Rieff, a philosopher who was researching on his 1955 book Eros and Civilization. 38 Sontag researched for Freud: The Moralist's (1959) before their divorce in 1958, and contributed to the book to the extent that she has been designated as an unofficial co-author. David Rieff, the couple's son, was also a writer in his own right and also served as his mother's editor at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Sontag was given a fellowship from the American Association of University Women (1958-1958) in Oxford, where she travelled without her husband and son. When attending J. L. Austin's B. Phil seminars and Isaiah Berlin's lectures, she took classes with Iris Murdoch, Stuart Hampshire, A. J. Ayer, and H. L. A. Hart. Oxford did not appeal to her, but she did move to the University of Paris after Michaelmas' term (the Sorbonne). Allan Bloom, Jean Wahl, Alfred Chester, Harriet Sohmers, and Marene Fornés were among the expat artists and scholars in Paris, including Allan Bloom, Jean Wahl, Jean Wahl, Alfred Chester, Harriet Sohmers, and Mara Irene Fornés. Sontag said that her time in Paris was perhaps the most crucial period of her life. 51-52 It was certainly the basis of her long-term intellectual and artistic connection with France's culture. While her literary fame grew, she moved to New York in 1959 to live with Fornés for the next seven years, regaining custody of her son and teaching at universities.: 53–54

Personal life

In 1986, Sontag's mother died of lung cancer in Hawaii.

Sontag died in New York City on December 28, 2004, at the age of 71, from myelodysplastic syndrome, which had progressed to acute myelogenous leukemia. She is buried in Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris. David Rieff, her son, has chronicled her illness.

Sontag was aware of her bisexuality as early as her teens. "I think I have lesbian tendencies" in her journal at 15, she wrote: "I reluctantly write this." "Perhaps I was inebriated, after all, because it was so beautiful when H began to propose to me at 16" she had a sexual encounter with a woman. It had been 4:00 p.m. before we had gone to bed... I was fully aware that I wanted her, but she knew it too."

Sontag lived with the letters 'H,' writer and model Harriet Sohmers Zwerling, who appeared in Berkeley from 1958 to 1959. Sontag was the partner of Mara Irene Fornés, a Cuban-American avant garde playwright and producer, before. Eva Kollisch, a German academic, and an Italian aristocrat were among Fornés' divorcees. Sontag was entangled in the American artists Jasper Johns and Paul Thek. Sontag lived with Nicole Stéphane, a Rothschild banking actress turned film actress, and later, choreographer Lucinda Childs. Joseph Brodsky, a writer, also had a friendship with him. Sontag married Annie Leibovitz in a long line from the late 1980s to her recent years.

Sontag had a close friendship with photographer Annie Leibovitz. They met in 1989, when neither had already demonstrated notability in their careers. Leibovitz has suggested that Sontag aided her and constructively critiqued her work. Neither woman announced whether the relationship was a personal or romantic in nature during Sontag's lifetime. Leibovitz's decade-plus friendship with Sontag was highlighted in Newsweek in 2006, with Leibovitz stating, "The two first met in the late '80s, when Leibovitz photographed her for a book jacket." They never lived together, though they did share an apartment within sight of each other's. "With Susan, it was a love tale," Leibovitz, who was interviewed for her 2006 book A Photographer's Life: 1990-2005, said. While Leibovitz's "companion" and "partner" were not in our vocabulary, Leibovitz's "companion" and "companion" were not in our vocabulary, "words such as 'companion' and 'partner' were not in our vocabulary," Leibovitz wrote in A Photographer's Life in 2009. We were two people who supported each other through our lives. "Mate is the closest word," says the narrator.' The descriptor "lover" in Leibovitz's year was correct, according to Leibovitz. "Call us 'lovers,' she said later.' I like 'lovers.' You know, 'lovers' sounds romantic.' I'm trying to be absolutely clear. Susan is my favorite actress.

Sontag was very open about bisexuality in an interview with the Guardian in 2000: he was in fact open about it.

Many of Sontag's obituaries failed to mention her significant same-sex relationships, most notable with Annie Leibovitz. Despite attempts to do so, Daniel Okrent, the public editor of The New York Times, supported the newspaper's obituary, arguing that there could be no credible evidence of her intimate relations with Leibovitz at the time of Sontag's death. Newsweek published an article about Annie Leibovitz, which made explicit references to her decade-plus relationship with Sontag following Sontag's death.

"I grew up in a time when the modus operandi was the 'open secret,' he said in Editor-in-Chief Brendan Lemon of Out magazine.' I'm used to it and it's quite fine. I'm not sure why I haven't shared more about my sexuality, but I do wonder if I haven't repressed anything here to my discredit. I may have assisted some people more if I had discussed my private sexuality more, but it has never been my primary aim to provide support to anyone in dire need. I'd rather have fun than have to worry about it."

Career

While working on her stories, Sontag taught philosophy at Sarah Lawrence College and City University of New York and the Philosophy of Religion with Jacob Taubes, Susan Taubes, Theodor Gaster, and Hans Jonas, in the Religion Department at Columbia University from 1960 to 1964. She held a writing fellowship at Rutgers University for 1964 to 1965 before ending her relationship with academia in favor of full-time freelance writing.: 56–57

At age 30, she published an experimental novel called The Benefactor (1963), following it four years later with Death Kit (1967). Despite a relatively small output, Sontag thought of herself principally as a novelist and writer of fiction. Her short story "The Way We Live Now" was published to great acclaim on November 24, 1986 in The New Yorker. Written in an experimental narrative style, it remains a significant text on the AIDS epidemic. She achieved late popular success as a best-selling novelist with The Volcano Lover (1992). At age 67, Sontag published her final novel In America (2000). The last two novels were set in the past, which Sontag said gave her greater freedom to write in the polyphonic voice:

She wrote and directed four films and also wrote several plays, the most successful of which were Alice in Bed and Lady from the Sea.

It was through her essays that Sontag gained early fame and notoriety. Sontag wrote frequently about the intersection of high and low art and expanded the dichotomy concept of form and art in every medium. She elevated camp to the status of recognition with her widely read 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp,'" which accepted art as including common, absurd and burlesque themes.

In 1977, Sontag published the series of essays On Photography. These essays are an exploration of photographs as a collection of the world, mainly by travelers or tourists, and the way we experience it. In the essays, she outlined her theory of taking pictures as you travel:

Sontag writes that the convenience of modern photography has created an overabundance of visual material, and "just about everything has been photographed.": 3 This has altered our expectations of what we have the right to view, want to view or should view. "In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notion of what is worth looking at and what we have the right to observe" and has changed our "viewing ethics.": 3 Photographs have increased our access to knowledge and experiences of history and faraway places, but the images may replace direct experience and limit reality.: 10–24 She also states that photography desensitizes its audience to horrific human experiences, and children are exposed to experiences before they are ready for them.: 20

Sontag continued to theorize about the role of photography in real life in her essay "Looking at War: Photography's View of Devastation and Death," which appeared in the December 9, 2002 issue of The New Yorker. There she concludes that the problem of our reliance on images and especially photographic images is not that "people remember through photographs but that they remember only the photographs ... that the photographic image eclipses other forms of understanding—and remembering. ... To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture" (p. 94).

She became a role-model for many feminists and aspiring female writers during the 1960s and 1970s.

Awards and honors

- 1976: Arts and Letters Award in Literature

- 1977: National Book Critics Circle Award for On Photography

- 1979: Beca member of the American Arts

- 1990: MacArthur Fellowship

- 1992: Malaparte Prize, Italy

- 1999: Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres, France

- 2000: National Book Award for In America

- 2001: Jerusalem Prize, awarded every two years to a writer whose work explores the freedom of the individual in society.

- 2002: George Polk Award, for Cultural Criticism for "Looking at War," in The New Yorker

- 2003: Honorary Doctorate of Tübingen University

- 2003: Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels during the Frankfurt Book Fair

- 2003: Prince of Asturias Award on Literature.

- 2004: Two days after her death, Muhidin Hamamdzic, the mayor of Sarajevo announced the city would name a street after her, calling her an "author and a humanist who actively participated in the creation of the history of Sarajevo and Bosnia." Theatre Square outside the National Theatre was promptly proposed to be renamed Susan Sontag Theatre Square. It took 5 years, however, for that tribute to become official. On January 13, 2010, the city of Sarajevo posted a plate with a new street name for Theater Square: Theater Square of Susan Sontag.