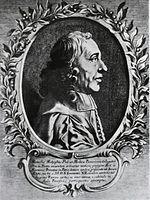

Marcello Malpighi

Marcello Malpighi was born in Crevalcore, Emilia-Romagna, Italy on March 10th, 1628 and is the Doctor. At the age of 66, Marcello Malpighi biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 66 years old, Marcello Malpighi physical status not available right now. We will update Marcello Malpighi's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Marcello Malpighi (10 March 1628 – 29 November 1694) was an Italian biologist and physician, who is referred to as the "Founder of microscopical anatomy, histology & Father of physiology and embryology".

Malpighi's name is born by several physiological features related to the biological excretory system, such as the Malpighian corpuscles and Malpighian pyramids of the kidneys and the Malpighian tubule system of insects.

The splenic lymphoid nodules are often called the "Malpighian bodies of the spleen" or Malpighian corpuscles.

The botanical family Malpighiaceae is also named after him.

He was the first person to see capillaries in animals, and he discovered the link between arteries and veins that had eluded William Harvey.

Malpighi was one of the earliest people to observe red blood cells under a microscope, after Jan Swammerdam.

His treatise De polypo cordis (1666) was important for understanding blood composition, as well as how blood clots.

In it, Malpighi described how the form of a blood clot differed in the right against the left sides of the heart.The use of the microscope enabled Malpighi to discover that invertebrates do not use lungs to breathe, but small holes in their skin called tracheae.

Malpighi also studied the anatomy of the brain and concluded this organ is a gland.

In terms of modern endocrinology, this deduction is correct because the hypothalamus of the brain has long been recognized for its hormone-secreting capacity.Because Malpighi had a wide knowledge of both plants and animals, he made contributions to the scientific study of both.

The Royal Society of London published two volumes of his botanical and zoological works in 1675 and 1679.

Another edition followed in 1687, and a supplementary volume in 1697.

In his autobiography, Malpighi speaks of his Anatome Plantarum, decorated with the engravings of Robert White, as "the most elegant format in the whole literate world."His study of plants led him to conclude that plants had tubules similar to those he saw in insects like the silk worm (using his microscope, he probably saw the stomata, through which plants exchange carbon dioxide with oxygen).

Malpighi observed that when a ring-like portion of bark was removed on a trunk a swelling occurred in the tissues above the ring, and he correctly interpreted this as growth stimulated by food coming down from the leaves, and being blocked above the ring.

Early years

Malpighi was born on 10 March 1628 at Crevalcore near Bologna, Italy. The son of well-to-do parents, Malpighi was educated in his native city, entering the University of Bologna at the age of 17. In a posthumous work delivered and dedicated to the Royal Society in London in 1697, Malpighi says he completed his grammatical studies in 1645, at which point he began to apply himself to the study of peripatetic philosophy. He completed these studies about 1649, where at the persuasion of his mother Frances Natalis, he began to study physics. When his parents and grandmother became ill, he returned to his family home near Bologna to care for them. Malpighi studied Aristotelian philosophy at the University of Bologna while he was very young. Despite opposition from the university authorities because he was non-Bolognese by birth, in 1653 he was granted doctorates in both medicine and philosophy. He later graduated as a medical doctor at the age of 25. Subsequently, he was appointed as a teacher, whereupon he immediately dedicated himself to further study in anatomy and medicine. For most of his career, Malpighi combined an intense interest in scientific research with a fond love of teaching. He was invited to correspond with the Royal Society in 1667 by Henry Oldenburg, and became a fellow of the society the next year.

In 1656, Ferdinand II of Tuscany invited him to the professorship of theoretical medicine at the University of Pisa. There Malpighi began his lifelong friendship with Giovanni Borelli, mathematician and naturalist, who was a prominent supporter of the Accademia del Cimento, one of the first scientific societies. Malpighi questioned the prevailing medical teachings at Pisa, tried experiments on colour changes in blood, and attempted to recast anatomical, physiological, and medical problems of the day. Family responsibilities and poor health prompted Malpighi's return in 1659 to the University of Bologna, where he continued to teach and do research with his microscopes. In 1661 he identified and described the pulmonary and capillary network connecting small arteries with small veins. Malpighi's views evoked increasing controversy and dissent, mainly from envy and lack of understanding on the part of his colleagues.

Career

In 1653, his father, mother, and grandmother being dead, Malpighi left his family villa and returned to the University of Bologna to study anatomy. In 1656, he was made a reader at Bologna, and then a professor of physics at Pisa, where he began to abandon the disputative method of learning and apply himself to a more experimental method of research. Based on this research, he wrote some Dialogues against the Peripatetics and Galenists (those who followed the precepts of Galen and were spearheaded at the University Bologna by fellow physician but inveterate foe Giovanni Girolamo Sbaraglia), which were destroyed when his house burned down. Weary of philosophical disputation, in 1660, Malpighi returned to Bologna and dedicated himself to the study of anatomy. He subsequently discovered a new structure of the lungs which led him to several disputes with the learned medical men of the times. In 1662, he was made a professor of physics at the Academy of Messina.

Retiring from university life to his villa in the country near Bologna in 1663, he worked as a physician while continuing to conduct experiments on the plants and insects he found on his estate. There he made discoveries of the structure of plants which he published in his Observations. At the end of 1666, Malpighi was invited to return to the public academy at Messina, which he did in 1667. Although he accepted temporary chairs at the universities of Pisa and Messina, throughout his life he continuously returned to Bologna to practice medicine, a city that repaid him by erecting a monument in his memory after his death.

As a physician, Malpighi's medical consultations with his patients, which were mostly those belonging to social elite classes, proved useful in better understanding the links between the human anatomy, disease pathology, and treatments for said diseases. Furthermore, Malpighi conducted his consultations not only by bedside, but also by post, using letters to request and conduct them for various patients. These letters served as social connections for the medical practices he performed, allowing his ideas to reach the public even in the face of criticism. These connections that Malpighi created in his practice became even more widespread due to the fact that he practiced in various countries. However, long distances complicated consults for some of his patients. The manner in which Malpighi practiced medicine also reveals that it was customary in his time for Italian patients to have multiple attending physicians as well as consulting physicians. One of Malpighi's principles of medical practice was that he did not rely on anecdotes or experiences concerning remedies for various illnesses. Rather, he used his knowledge of human anatomy and disease pathology to practice what he denoted as "rational" medicine ("rational" medicine was in contrast to "empirics"). Malpighi did not abandon traditional substances or treatments, but he did not employ their use simply based on past experiences that did not draw from the nature of the underlying anatomy and disease process. Specifically in his treatments, Malpighi's goal was to reset fluid imbalances by coaxing the body to correct them on its own. For example, fluid imbalances should be fixed over time by urination and not by artificial methods such as purgatives and vesicants. In addition to Malpighi's "rational" approaches, he also believed in so-called "miraculous," or "supernatural" healing. For this to occur, though, he argued that the body could not have attempted to expel any malignant matter, such as vomit. Cases in which this did occur, when healing could not be considered miraculous, were known as "crises."

In 1668, Malpighi received a letter from Mr. Oldenburg of the Royal Society in London, inviting him to correspond. Malpighi wrote his history of the silkworm in 1668, and sent the manuscript to Mr. Oldenburg. As a result, Malpighi was made a member of the Royal Society in 1669. In 1671, Malpighi's Anatomy of Plants was published in London by the Royal Society, and he simultaneously wrote to Mr. Oldenburg, telling him of his recent discoveries regarding the lungs, fibers of the spleen and testicles, and several other discoveries involving the brain and sensory organs. He also shared more information regarding his research on plants. At that time, he related his disputes with some younger physicians who were strenuous supporters of the Galenic principles and opposed to all new discoveries. Following many other discoveries and publications, in 1691, Malpighi was invited to Rome by Pope Innocent XII to become papal physician and professor of medicine at the Papal Medical School. He remained in Rome until his death.

Marcello Malpighi is buried in the church of Santi Gregorio e Siro, in Bologna, where nowadays can be seen a marble monument to the scientist with an inscription in Latin remembering – among other things – his "SUMMUM INGENIUM / INTEGERRIMAM VITAM / FORTEM STRENUAMQUE MENTEM / AUDACEM SALUTARIS ARTIS AMOREM" (great genius, honest life, strong and tough mind, daring love for the medical art).