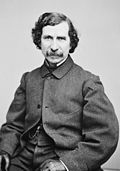

James K. Polk

James K. Polk was born in Pineville, North Carolina, United States on November 2nd, 1795 and is the US President. At the age of 53, James K. Polk biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 53 years old, James K. Polk physical status not available right now. We will update James K. Polk's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

By the time the legislature adjourned its session in September 1822, Polk was determined to be a candidate for the Tennessee House of Representatives. The election was in August 1823, almost a year away, allowing him ample time for campaigning. Already involved locally as a member of the Masons, he was commissioned in the Tennessee militia as a captain in the cavalry regiment of the 5th Brigade. He was later appointed a colonel on the staff of Governor William Carroll, and was afterwards often referred to as "Colonel". Although many of the voters were members of the Polk clan, the young politician campaigned energetically. People liked Polk's oratory, which earned him the nickname "Napoleon of the Stump." At the polls, where Polk provided alcoholic refreshments for his voters, he defeated incumbent William Yancey.

Beginning in early 1822, Polk courted Sarah Childress—they were engaged the following year and married on January 1, 1824, in Murfreesboro. Educated far better than most women of her time, especially in frontier Tennessee, Sarah Polk was from one of the state's most prominent families. During James's political career Sarah assisted her husband with his speeches, gave him advice on policy matters, and played an active role in his campaigns. Rawley noted that Sarah Polk's grace, intelligence and charming conversation helped compensate for her husband's often austere manner.

Polk's first mentor was Grundy, but in the legislature, Polk came increasingly to oppose him on such matters as land reform, and came to support the policies of Andrew Jackson, by then a military hero for his victory at the Battle of New Orleans (1815). Jackson was a family friend to both the Polks and the Childresses—there is evidence Sarah Polk and her siblings called him "Uncle Andrew"—and James Polk quickly came to support his presidential ambitions for 1824. When the Tennessee Legislature deadlocked on whom to elect as U.S. senator in 1823 (until 1913, legislators, not the people, elected senators), Jackson's name was placed in nomination. Polk broke from his usual allies, casting his vote for Jackson, who won. The Senatge seat boosted Jackson's presidential chances by giving him current political experience to match his military accomplishments. This began an alliance that would continue until Jackson's death early in Polk's presidency. Polk, through much of his political career, was known as "Young Hickory", based on the nickname for Jackson, "Old Hickory". Polk's political career was as dependent on Jackson as his nickname implied.

In the 1824 United States presidential election, Jackson got the most electoral votes (he also led in the popular vote) but as he did not receive a majority in the Electoral College, the election was thrown into the U.S. House of Representatives, which chose Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who had received the second-most of each. Polk, like other Jackson supporters, believed that Speaker of the House Henry Clay had traded his support as fourth-place finisher (the House may only choose from among the top three) to Adams in a Corrupt Bargain in exchange for being the new Secretary of State. Polk had in August 1824 declared his candidacy for the following year's election to the House of Representatives from Tennessee's 6th congressional district. The district stretched from Maury County south to the Alabama line, and extensive electioneering was expected of the five candidates. Polk campaigned so vigorously that Sarah began to worry about his health. During the campaign, Polk's opponents said that at the age of 29 Polk was too young for the responsibility of a seat in the House, but he won the election with 3,669 votes out of 10,440 and took his seat in Congress later that year.

When Polk arrived in Washington, D.C. for Congress's regular session in December 1825, he roomed in Benjamin Burch's boarding house with other Tennessee representatives, including Sam Houston. Polk made his first major speech on March 13, 1826, in which he said that the Electoral College should be abolished and that the president should be elected by popular vote. Remaining bitter at the alleged Corrupt Bargain between Adams and Clay, Polk became a vocal critic of the Adams administration, frequently voting against its policies. Sarah Polk remained at home in Columbia during her husband's first year in Congress, but accompanied him to Washington beginning in December 1826; she assisted him with his correspondence and came to hear James's speeches.

Polk won re-election in 1827 and continued to oppose the Adams administration. He remained in close touch with Jackson, and when Jackson ran for president in 1828, Polk was an advisor on his campaign. Following Jackson's victory over Adams, Polk became one of the new President's most prominent and loyal supporters. Working on Jackson's behalf, Polk successfully opposed federally-funded "internal improvements" such as a proposed Buffalo-to-New Orleans road, and he was pleased by Jackson's Maysville Road veto in May 1830, when Jackson blocked a bill to finance a road extension entirely within one state, Kentucky, deeming it unconstitutional. Jackson opponents alleged that the veto message, which strongly complained about Congress' penchant for passing pork barrel projects, was written by Polk, but he denied this, stating that the message was entirely the President's.

Polk served as Jackson's most prominent House ally in the "Bank War" that developed over Jackson's opposition to the re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States. The Second Bank, headed by Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia, not only held federal dollars but controlled much of the credit in the United States, as it could present currency issued by local banks for redemption in gold or silver. Some Westerners, including Jackson, opposed the Second Bank, deeming it a monopoly acting in the interest of Easterners. Polk, as a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, conducted investigations of the Second Bank, and though the committee voted for a bill to renew the bank's charter (scheduled to expire in 1836), Polk issued a strong minority report condemning the bank. The bill passed Congress in 1832, but Jackson vetoed it and Congress failed to override the veto. Jackson's action was highly controversial in Washington but had considerable public support, and he won easy re-election in 1832.

Like most Southerners, Polk favored low tariffs on imported goods, and initially sympathized with John C. Calhoun's opposition to the Tariff of Abominations during the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, but came over to Jackson's side as Calhoun moved towards advocating secession. Thereafter, Polk remained loyal to Jackson as the President sought to assert federal authority. Polk condemned secession and supported the Force Bill against South Carolina, which had claimed the authority to nullify federal tariffs. The matter was settled by Congress passing a compromise tariff.

In December 1833, after being elected to a fifth consecutive term, Polk, with Jackson's backing, became the chairman of Ways and Means, a powerful position in the House. In that position, Polk supported Jackson's withdrawal of federal funds from the Second Bank. Polk's committee issued a report questioning the Second Bank's finances and another supporting Jackson's actions against it. In April 1834, the Ways and Means Committee reported a bill to regulate state deposit banks, which, when passed, enabled Jackson to deposit funds in pet banks, and Polk got legislation passed to allow the sale of the government's stock in the Second Bank.

In June 1834, Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson resigned from Congress to become Minister to the United Kingdom. With Jackson's support, Polk ran for speaker against fellow Tennessean John Bell, Calhoun disciple Richard Henry Wilde, and Joel Barlow Sutherland of Pennsylvania. After ten ballots, Bell, who had the support of many opponents of the administration, defeated Polk. Jackson called in political debts to try to get Polk elected Speaker of the House at the start of the next Congress in December 1835, assuring Polk in a letter he meant him to burn that New England would support him for speaker. They were successful; Polk defeated Bell to take the speakership.

According to Thomas M. Leonard, "by 1836, while serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives, Polk approached the zenith of his congressional career. He was at the center of Jacksonian Democracy on the House floor, and, with the help of his wife, he ingratiated himself into Washington's social circles." The prestige of the speakership caused them to move from a boarding house to their own residence on Pennsylvania Avenue. In the 1836 presidential election, Vice President Martin Van Buren, Jackson's chosen successor, defeated multiple Whig candidates, including Tennessee Senator Hugh Lawson White. Greater Whig strength in Tennessee helped White carry his state, though Polk's home district went for Van Buren. Ninety percent of Tennessee voters had supported Jackson in 1832, but many in the state disliked the destruction of the Second Bank, or were unwilling to support Van Buren.

As Speaker of the House, Polk worked for the policies of Jackson and later Van Buren. Polk appointed committees with Democratic chairs and majorities, including the New York radical C. C. Cambreleng as the new Ways and Means chair, although he tried to maintain the speaker's traditional nonpartisan appearance. The two major issues during Polk's speakership were slavery and, after the Panic of 1837, the economy. Polk firmly enforced the "gag rule", by which the House of Representatives would not accept or debate citizen petitions regarding slavery. This ignited fierce protests from John Quincy Adams, who was by then a congressman from Massachusetts and an abolitionist. Instead of finding a way to silence Adams, Polk frequently engaged in useless shouting matches, leading Jackson to conclude that Polk should have shown better leadership. Van Buren and Polk faced pressure to rescind the Specie Circular, Jackson's 1836 order that payment for government lands be in gold and silver. Some believed this had led to the crash by causing a lack of confidence in paper currency issued by banks. Despite such arguments, with support from Polk and his cabinet, Van Buren chose to back the Specie Circular. Polk and Van Buren attempted to establish an Independent Treasury system that would allow the government to oversee its own deposits (rather than using pet banks), but the bill was defeated in the House. It eventually passed in 1840.

Using his thorough grasp of the House's rules, Polk attempted to bring greater order to its proceedings. Unlike many of his peers, he never challenged anyone to a duel no matter how much they insulted his honor. The economic downturn cost the Democrats seats, so that when he faced re-election as Speaker of the House in December 1837, he won by only 13 votes, and he foresaw defeat in 1839. Polk by then had presidential ambitions but was well aware that no Speaker of the House had ever become president (Polk is still the only one to have held both offices). After seven terms in the House, two as speaker, he announced that he would not seek re-election, choosing instead to run for Governor of Tennessee in the 1839 election.

In 1835, the Democrats had lost the governorship of Tennessee for the first time in their history, and Polk decided to return home to help the party. Tennessee was afire for White and Whiggism; the state had reversed its political loyalties since the days of Jacksonian domination. As head of the state Democratic Party, Polk undertook his first statewide campaign, He opposed Whig incumbent Newton Cannon, who sought a third two-year term as governor. The fact that Polk was the one called upon to "redeem" Tennessee from the Whigs tacitly acknowledged him as head of the state Democratic Party

Polk campaigned on national issues, whereas Cannon stressed state issues. After being bested by Polk in the early debates, the governor retreated to Nashville, the state capital, alleging important official business. Polk made speeches across the state, seeking to become known more widely than just in his native Middle Tennessee. When Cannon came back on the campaign trail in the final days, Polk pursued him, hastening the length of the state to be able to debate the governor again. On Election Day, August 1, 1839, Polk defeated Cannon, 54,102 to 51,396, as the Democrats recaptured the state legislature and won back three congressional seats.

Tennessee's governor had limited power—there was no gubernatorial veto, and the small size of the state government limited any political patronage. But Polk saw the office as a springboard for his national ambitions, seeking to be nominated as Van Buren's vice presidential running mate at the 1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in May. Polk hoped to be the replacement if Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson was dumped from the ticket; Johnson was disliked by many Southern whites for fathering two daughters by a biracial mistress and attempting to introduce them into white society. Johnson was from Kentucky, so Polk's Tennessee residence would keep the New Yorker Van Buren's ticket balanced. The convention chose to endorse no one for vice president, stating that a choice would be made once the popular vote was cast. Three weeks after the convention, recognizing that Johnson was too popular in the party to be ousted, Polk withdrew his name. The Whig presidential candidate, General William Henry Harrison, conducted a rollicking campaign with the motto "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", easily winning both the national vote and that in Tennessee. Polk campaigned in vain for Van Buren and was embarrassed by the outcome; Jackson, who had returned to his home, the Hermitage, near Nashville, was horrified at the prospect of a Whig administration. In the 1840 election, Polk received one vote from a faithless elector in the electoral college's vote for U.S. Vice President. Harrison's death after a month in office in 1841 left the presidency to Vice President John Tyler, who soon broke with the Whigs.

Polk's three major programs during his governorship; regulating state banks, implementing state internal improvements, and improving education all failed to win the approval of the legislature. His only major success as governor was his politicking to secure the replacement of Tennessee's two Whig U.S. senators with Democrats. Polk's tenure was hindered by the continuing nationwide economic crisis that had followed the Panic of 1837 and which had caused Van Buren to lose the 1840 election.

Encouraged by the success of Harrison's campaign, the Whigs ran a freshman legislator from frontier Wilson County, James C. Jones against Polk in 1841. "Lean Jimmy" had proven one of their most effective gadflies against Polk, and his lighthearted tone at campaign debates was very effective against the serious Polk. The two debated the length of Tennessee, and Jones's support of distribution to the states of surplus federal revenues, and of a national bank, struck a chord with Tennessee voters. On election day in August 1841, Polk was defeated by 3,000 votes, the first time he had been beaten at the polls. Polk returned to Columbia and the practice of law and prepared for a rematch against Jones in 1843, but though the new governor took less of a joking tone, it made little difference to the outcome, as Polk was beaten again, this time by 3,833 votes. In the wake of his second statewide defeat in three years, Polk faced an uncertain political future.