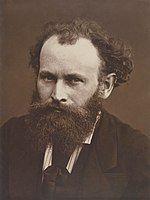

Edouard Manet

Edouard Manet was born in Paris, Île-de-France, France on January 23rd, 1832 and is the Painter. At the age of 51, Edouard Manet biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 51 years old, Edouard Manet physical status not available right now. We will update Edouard Manet's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Édouard Manet (UK: South : French: [edwa man]; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, as well as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Manet was born in a wealthy family with strong political ties; he turned down a naval career that had been envisioned for him; he became engrossed in painting. The Luncheon on the Grass, his early masterworks (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) and Olympia, both 1863, caused a lot of controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. These are the first paintings to date that mark the beginning of modern art. Manet's last 20 years of life aided him in creating friendships with other great artists of the time; he designed his own distinctive and precise style that would be heralded as influential and a major influence on young painters.

Early life

Édouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832, in the ancestral hôtel particulier (mansion) on the Rue des Petits Augustins (now Rue Bonaparte) to an upscale and well-connected family. Eugénie-Desirée Fournier's mother was the niece of Swedish crown prince Charles Bernadotte's daughter and heir, from whom the Swedish monarchs are descended. Édouard's father, Auguste Manet, was a French judge who wished that Édouard would pursue a career in law. Edmond Fournier, his uncle, encouraged him to learn painting and brought young Manet to the Louvre. He began attending secondary school, the Collège Rollin, in 1841. Manet began learning in 1845, on the advice of his uncle, where he encountered Antonin Proust, the future Minister of Fine Arts and subsequent lifelong friend.

In 1848, he sailed on a training ship to Rio de Janeiro at his father's request. After failing the aptitude test twice to join the Navy, his father resigned to his desire to pursue an art education. Manet under the instruction of academic painter Thomas Couture from 1850 to 1856. Manet copied the Old Masters in the Louvre in his spare time.

Manet lived in Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, where he was inspired by Dutch painter Frans Hals and Spanish artists Diego Velázquez and Francisco José de Goya from 1853 to 1856.

Career

Manet founded a studio in 1856. His style in this period was characterized by loosening forest strokes, simplifying of information, and the loss of transitional tones. He painted The Absinthe Drinker (1858-59) and other popular topics such as beggars, actors, Gypsies, people in cafes, and bullfights, adopting Gustave Courbet's new style of realism. He rarely painted religious, mythological, or historical subjects in his early life; in the Art Institute of Chicago, his Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers include his Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers and The Dead Christ with Angels, 1864. In 1861, Manet received two canvases at the Salon. Critics also dismissed a portrait of his mother and father, who at the time was A stroke was robbed of speech by a stroke. The other, The Spanish Singer, was adored by Théophile Gautier and moved in a more prominent position as a result of its fame among Salon-goers. Any young artists were fascinated by Manet's work, which seemed "slightly slapdash" when compared to so many other Salon exhibitions' rigorous style. "Strange new style[?] by the Spanish singer, whose eyes opened and jaws dropped," many painters' eyes opened and jaws dropped."

Manet's painterly style is shown by the Tuileries' music. It is a harbinger of his lifelong obsession with leisure, influenced by Hals and Velázquez.

Although the photograph was considered unfinished by some, the simulated atmosphere gives one a glimpse of what the Tuileries gardens looked like at the time; one could imagine the music and discussion.

Manet has depicted his acquaintances, writers, editors, and musicians who participate, as well as musicians, writers, poets, and writers, among other subjects.

The Luncheon on the Grass, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe), Le Bain's oldest work, is Le Bain's Le Bain. In 1863, the Paris Salon refused to show it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected), a related exhibition to the official Salon, in the Palais des Champs-Elysée. Emperor Napoleon III's Salon des Refusés was introduced as a solution to a difficult situation that had arisen during the Salon's selection Committee, which had rejected 2,783 paintings of the c. 5000. Each painter could choose whether or not they wanted to exhibit at the Salon des Refusés, but only about 500 of the rejected painters decided to do so.

Model Victorine Meurent, his wife Suzanne, Ferdinand Leenhoff, his future brother-in-law Ferdinand Leenhoff, and one of his brothers posed. Meurent was also responsible for several more of Manet's most important works, including Olympia; by the mid-70s, she was a professional painter in her own right.

The painting's juxtaposition of fully dressed men and a nude woman was both contested and sketch-like execution, an innovation that distinguished Manet from Courbet. Manet's composition reveals his study of the old masters, as the figure's disposition is derived from Marcantonio Raimondi's engraving of the Judgement of Paris (c. 1515) based on a drawing by Raphael.

Two other works that have been cited as significant examples for Le déjeuner sur l'herbe are Pastoral Concert (c. 1510, The Louvre) and The Tempest (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice), both of which can be traced in various ways to Italian Renaissance masters Giorgione or Titian. In a rural setting, the Tempest is an enigmatic work starring a completely dressed man and a nude woman. The man is standing to the left and gazing to the side, apparently at the woman, who is seated and breastfeeding a baby; the two figures' relationship is uncertain. Two dressed men and a nude woman are seated on the grass, engaged in song making, while a second nude woman stands beside them.

Manet repeated his appreciation for a fine Renaissance artist's work in the painting Olympia (1863), a nude depicted in a style reminiscent of early studio photographs, but his pose was based on Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538). The painting is also reminiscent of Francisco Goya's painting The Nude Maja (1800).

After being asked to bring a nude painting to the Salon, a manet took the canvas. The Paris Salon in 1865, where it caused a scandal, accepted his open portrayal of a self-assured prostitute. "Only the precautions taken by the government prevented the painting from being punctured and torn" by offended viewers, according to Antonin Proust. The painting was partially controversial because the nude was wearing only modest clothing, such as an orchid, a necklace, a ribbon around her neck, and mule slippers, all of which emphasised her nakedness, sexuality, and a cosmopolitan lifestyle. The orchid, upswept hair, black cat, and a bouquet of flowers were all typical sexual symbols at the time. This modern Venus' body is thin, counter to current expectations; the painting's lack of insight rankled viewers. The painting's flatness, which was inspired by Japanese wood block art, makes the nude more human and less voluptuous. A fully dressed black servant is on display, promoting the then-current belief that black people were hypersexed. The fact that she is wearing the clothing of a servant to a courtesan contributes to the piece's sexual sensitivity.

Olympia's body as well as her gaze is unashamedly combative. As her servant gives flowers from one of her male suitors, she defiantly looks out. Though she has her hand rests on her leg, masking her pubic position, the inference of traditional female virtue is ironic; a notion of modesty is strangely absent in this work. A contemporary observer condemned Olympia's "shamelessly flexed" left hand, causing him to mock Titian's Venus's relaxed, shielding hand. In comparison to Titian's portrayal of the goddess in his Venus of Urbino, the alert black cat at the foot of the bed strikes a sexually rebellious note.

In the popular press, Olympia was depicted by caricatures, but the French avant-garde community embraced the painting's significance, and artists such as Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and later Paul Gauguin celebrated its significance, whose work was lauded.

The painting, as with Luncheon on the Grass, raised the question of prostitution in contemporary France and the roles of women in society.

Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff in 1863 at a Protestant church after his father's death in 1862. Leenhoff, a Dutch-born piano teacher, was a mentor for two years Manet's senior, who had been romantically involved for about ten years. Leenhoff was hired by Manet's father, Auguste, to instruct Manet and his younger brother piano. She may have been Auguste's mistress. Leenhoff gave birth to Leon Koella Leenhoff, a boy born out of wedlock in 1852.

The manet painted his wife in The Reading, among other works. Leon Leenhoff, her son, who may have been one of the Manets, posed often for Manet. He is most well-known as the subject of the Boy Carrying a Sword of 1861 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). In the background of The Balcony (1868-69), he appears as the boy holding a tray.

Manet met with Impressionists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro through Berthe Morisot, a member of the group who welcomed him into the group and lured him into their activities. They became popular as the Batignolles group later (Le groupe des Batignolles).

Morisot's ostensible grand-niece was unveiled in the Salon de Paris in 1864 and she continued to exhibit in the salon for the next ten years.

In 1868, Manet became Morisot's friend and colleague. She is credited with persuading Manet to attempt plein air painting, which she had been doing since she was introduced to it by a friend of hers, Camille Corot. Manet and her artist had a reciprocating friendship, and she's included some of her techniques into his artwork. When she married Eugène's brother, she became his sister-in-law in 1874.

Manet, a founding member of Impressionism, argued that modern artists should exhibit at the Paris Salon rather than abandoning it in favor of independent shows rather than abandoning it in favour of independent exhibits. Nevertheless, when Manet was refused admission to the International Exhibition of 1867, he created his own exhibition. His mother was worried that he would waste all his inheritance on this venture, which was prohibitively costly. Though the exhibition received poor feedback from the major critics, it also introduced Degas to his first interactions with many future Impressionist painters.

Manet held off participation in Impressionist exhibitions partly because he did not want to be seen as the representative of a national identity and partially because he chose Salon exhibits. Eva Gonzalès, the niece of novelist Emmanuel Gonzalès, was his only formal student.

Monet and Morisot, for example, influenced him. Manet's use of lighter shades shows that he made less use of dark backgrounds in the early 1870s, but maintained his distinctive use of black, uncharacteristic of Impressionist painting. He created several outside (plein air) pieces, but the studio's serious work was still present.

Manet enjoyed a close friendship with composer Emmanuel Chabrier, who created two portraits of him; the musician owned 14 of Manet's paintings and dedicated his Impromptu to Manet's wife.

The "semimondaine" Méry Laurent, one of Manet's most popular models in the 1880s, posed for seven portraits in pastel. Many French (and even American) writers and painters of her time appeared in Laurent's salons; Manet had links and clout through such events;

Manet could have been one of his champions throughout his life, although art critics resisted him publicly in the press, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Charles Baudelaire, who challenged him to live as it was. Each of them was drew or painted by a manet in turn.

Manet's paintings of café scenes are glimpses of social life in 19th-century Paris. People are depicted as drinking beer, listening to music, flirting, reading, or waiting. Many of these paintings were based on sketches that were created on site. On boulevard de Rochechourt, manet frequented the Brasserie Reichshoffen, where he based At the Cafe in 1878. Several people are in the bar, and one woman confronts the viewer while others wait to be served. Such representations depict a flâneur's painted journal. These are painted in a loosening style, alluding to Hals and Velázquez, but they capture the atmosphere and feeling of Parisian night life. They are painted snapshots of bohemianism, urban workers, as well as some of the bourgeoisie.

A man smokes in the corner of a Café-Concert, while a waitress serves drinks. A woman enjoys her beer in the company of a friend in The Beer Drinkers. A sophisticated gentleman sits at a bar while a waitress stands resolutely in the background, sipping her drink in The Café-Concert, as shown at right. A serving woman pauses for a moment behind a seated customer smoking a pipe, while a ballet dancer with arms out as she prepares to turn is on stage in the background.

Pere Lathuille's restaurant on the Avenue de Clichy, which had a garden in addition to the dining room, was also seated by a manet. Chez le père Lathuille (At Pere Lathuille's) was one of his paintings that was on display at the gallery, in which a man displays an unrequited fascination in a woman dining near him.

A large, cheerful, bearded man sits with a pipe in one hand and a glass of beer in the other, staring straight at the viewer.

The upper class was depicted in more formal social gatherings, according to a manet. Manet catches a large audience of people attending a dance in Masked Ball at the Opera. When speaking to women with masks and costumes, men stand with top hats and long black suits. In this picture, he included portraits of his friends.

In the dining room of the Manet house, his 1868 painting The Luncheon was unveiled.

In his career, a manet portrayed other common interests. An unusual viewpoint is used in Longchamp's Races to highlight the racehorses' ferocious energy as they approach the viewer. Manet's Skating depicts a well-dressed woman in the foreground, while others skate behind her. Often there is the sense of vibrant urban life behind the subject, expanding outside the canvas's boundaries.

Soldiers are relaxed, seated, and standing at the International Exhibition, while wealthy couples are engaged. A gardener, a boy with a dog, and a lady on horseback are among the subjects and ages of Paris's inhabitants.

Manet's contribution to modern life featured works dedicated to war, as well as current interpretations of "history painting" as a result of recent interpretations of the genre. The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864), a sea skirmish that took place off the coast of France, may have been seen by the artist, was the artist's first such work.

The French involvement in Mexico came next; Manet created three versions of Emperor Maximilian's Execution, which sparked questions about French foreign and domestic policy. Manet's Execution's various interpretations are among the artist's most important works, meaning that the subject was one of the painter's most important. Its subject is the execution of a Habsburg emperor by a Mexican firing squad who had been installed by Napoleon III. In France, neither the paintings nor a lithograph of the subject were allowed to be displayed. The paintings depict Goya and Picasso's Guernica as an indictment of formalized slaughter.

Manet, a man from Oloron-Sainte-Marie in the Pyrenees, travelled in January 1871. In his absence, his colleagues added his name to the "Fédération des artistes" (see: Courbet) of the Paris Commune. Manet stayed away from Paris, perhaps until the week sanglante: "We came back to Paris a few days ago," says Berthe Morisot (10 June 1871) "The semaine sanglante came to an end."

Manet, The Barricade's prints and drawings collection contains a watercolour/gouache series based on a lithograph of Maximilian's execution. A private collector has acquired The Barricade (oil on plywood).

"I never imagined that you would be represented by such doddering old fools, not excepting the little twit Thiers of the Commune," he wrote to his (confederate) friend Félix Bracquemond in Paris on 18 March 1871. Lucien Henry, a communard, was known to have been a former painter's model and Millière, an insurance agent. "These bloodthirsty caperings are for the arts, and it's an inspiration!" However, there is at least one consolation in our misdeeds: we're not politicians and have no desire to be voted as deputies."

Manet admired the republican Léon Gambetta the most. Manet opened his atelier to a republican electoral meeting chaired by Gambetta's friend Eugène Spuller in the midst of the seize mai coup in 1877.

In his paintings, a manet depicted several scenes of Paris's streets. On either side of the street, the Rue Mosnier Decked with Flags depicts red, white, and blue pennants; another painting of the same name depicts a one-legged man walking with crutches. Rue Mosnier with Pavers, depicting the same street but in a different context, where people and horses are moving past.

In 1873, the Gare Saint-Lazare Railway, which is also known as The Gare Saint-Lazare, was painted. The setting is the late 19th century's urban landscape of Paris. Victorine Meurent, a fellow painter and Olympia and the Luncheon on the Grass, stands before an iron fence with a sleeping puppy and an open book in her lap, based on her favorite model in his last painting. A little girl with her back to the painter is next to her, watching a train pass beneath them.

Manet opts for the iron grating which "boldly stretches across the canvas" as the backdrop for an outdoor scene rather than selecting the natural scenery as a backdrop for an outdoor scene. The only hint of the train is its white cloud of steam. Modern apartment buildings can be seen in the distance. The foreground is brought into sharper focus by this arrangement. Deep space's old fashion is dismissed.

"Visitors and commentators found the reception this painting received at the official Paris Salon of 1874: "Visitors and commentators found it baffling, its design incoherent, and execution sketchy," historian Isabelle Dervaux wrote about it. Caricaturists mocked Manet's photograph, in which only a few people recognized the symbol of modernity that it has adopted today." The work is on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., at the National Gallery of Art.

In 1874, a manet painted several boating subjects. Boating, which is now on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, exemplifies in its conciseness, while the image's abrupt cropping by the boat's frame and sail contributes to the image's immediacy.

A book-length French translation of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven's 1875 featured lithographs by Manet and translation by Mallarmé.

Manet was honoured the Légion d'honneur in 1881, after being pressured by his buddy Antonin Proust.

Manet's health in his mid-forties deteriorated, and he suffered severe pain and partial paralysis in his legs. He started receiving hydrotherapy therapy at a spa near Meudon in 1879 to solve what he felt was a circulatory disease, but in truth, he was suffering from locomotor ataxia, a common side-effect of syphilis. He made a portrait of Émilie Ambre as Carmen in 1880. Ambre and her companion Gaston de Beauplane had an estate in Meudon and curated the first exhibition of Emperor Maximilian's Execution in New York in December 1879.

Manet has created several small-scale still lifes of fruits and vegetables, including A Bunch of Asparagus and The Lemon (both 1880). In 1882, he completed A Bar at the Follies-Bergère (Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère), his last major work, and it stayed in the Salon that year. He resigned from small formats after that. His last paintings were made with flowers in glass vases.