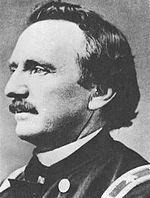

William F. Raynolds

William F. Raynolds was born in Canton, Ohio, United States on March 17th, 1820 and is the U.S. Army Surveyor And Topographer. At the age of 74, William F. Raynolds biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 74 years old, William F. Raynolds physical status not available right now. We will update William F. Raynolds's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Initially appointed a brevet second lieutenant in the 5th U.S. Infantry, within a few weeks Raynolds was transferred to the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. The Topographical Engineers performed surveys and developed maps for army use until their merger with the Corps of Engineers in 1863. Raynolds's first assignments from 1843 to 1844 were as an assistant topographical engineer involved in improving navigation on the Ohio River and surveying the northeastern boundary of the U.S. between 1844 and 1847.

When war with Mexico seemed imminent, topographic engineers were sent to the border to assist with the army's preparations. Raynolds served in Winfield Scott's Mexican–American War campaign that marched overland to Mexico City from the Gulf of Mexico seaport at Veracruz. After the war, the American army occupied Mexico City and the surrounding region. During the occupation, Raynolds and others set out to map and explore nearby mountains. Raynolds's party is credited with being the first confirmed to climb to the summit of Pico de Orizaba (19°01′48″N 97°16′12″W), which at 18,620 feet (5,680 m), is the tallest mountain in Mexico and third tallest in North America. Over a period of several months, Raynolds and other officers from both the army and navy mapped the best approach route to Pico de Orizaba. To assist them in their climb, the party planned on taking grapnels attached to long ropes and primitive crampons in the form of shoes with projecting points to help ensure they could safely climb up cliffs and across glaciers. Told by local villagers that any attempt to reach the summit would be fruitless because no one had ever done it before, the Americans became even more determined to show the Mexicans it could be climbed.

As the expedition left to ascend the mountain, a long pack train of nearly fifty officers, soldiers and native guides departed from the town of Orizaba in early May 1848. After several days of hiking through dense jungle, the expedition slowly gained altitude and established a base camp at 12,000 ft (3,700 m). Starting from base camp in the early morning of May 10 nearly two dozen climbers made the final push to the top of the mountain, but only Raynolds and a few others reached the summit. According to mountaineer and author Leigh N. Ortenburger, this feat may have inadvertently set the American mountaineering altitude record for the next fifty years. Raynolds estimated the summit of Pico de Orizaba to be 17,907 ft (5,458 m) above sea level, which was slightly greater than previous estimates but below the modern known altitude. As no higher peaks were known in North America at that time, Raynolds believed Pico de Orizaba was the tallest mountain on the continent. The summit crater was covered in snow but estimated to be between 400 to 650 yards (370 to 590 m) in diameter and 300 ft (91 m) deep. The American achievement was disputed by the Mexicans until an 1851 French expedition discovered an American flag on the summit with the year 1848 carved in the flagpole.

After returning from Mexico, Raynolds resumed mapping the U.S.–Canada border which he had been surveying before the war, then embarked on a project to develop water resources for the nation's growing capital of Washington, D.C. Raynolds traveled the Great Lakes for several years surveying and mapping shorelines while identifying potential lighthouse locations. After promotion to first lieutenant and then captain, in 1857 he was assigned to design and supervise the construction of lighthouses along the Jersey Shore and the Delmarva Peninsula regions. in the late 1850s Raynolds supervised construction of the Fenwick Island Light in Delaware and the Cape May Light in New Jersey. In 1859, Raynolds was working on finishing the Jupiter Inlet Light in Jupiter, Florida, when he was reassigned to lead the first U.S. Government-sponsored expedition to explore the Yellowstone region.

In early 1859, Raynolds was charged with leading an expedition into the Yellowstone region of Montana and Wyoming to determine, "as far as practicable, everything relating to ... the Indians of the country, its agricultural and mineralogical resources ... the navigability of its streams, its topographical features, and the facilities or obstacles which the latter present to the construction of rail or common roads ..." The expedition was carried out by a handful of technicians, including photographer and topographer James D. Hutton, artist and mapmaker Anton Schönborn, and geologist and naturalist Ferdinand V. Hayden, who led several later expeditions to the Yellowstone region. Raynolds's second-in-command was lieutenant Henry E. Maynadier. The expedition was supported by a small infantry detachment of 30 and was federally funded with $60,000. Experienced mountain man Jim Bridger was hired to guide the expedition.

The expedition started in late May 1859 at St. Louis, Missouri, then was transported by two steamboats up the Missouri River to New Fort Pierre, South Dakota. In late June the expedition left New Fort Pierre and headed overland to Fort Sarpy where they encountered the Crow Indians. Raynolds said the Crow were a "small band compared to their neighbors, but are famous warriors, and, according to common report, seldom fail to hold their own with any of the tribes unless greatly outnumbered." Raynolds was impressed with Chief Red Bear and, after assuring him the expedition meant only to pass through their territory and not linger, traded with the Crow for seven horses.

Raynolds divided his expedition, sending a smaller detachment under Maynadier to explore the Tongue River, a major tributary of the Yellowstone River. Two of Maynadier's party, James D. Hutton and Zephyr Recontre, the expedition's Sioux interpreter, took a side trip to locate and investigate an isolated rock formation that had been seen from great distance by a previous expedition in 1857. Hutton was the first person of European descent to reach this rock formation in northeastern Wyoming, later known as Devils Tower; Raynolds never elaborated on this event, mentioning it only in passing. By September 2, 1859, Raynolds's detachment had followed the Yellowstone River to the confluence with the Bighorn River in south-central Montana. The two parties under Raynolds and Maynadier reunited on October 12, 1859 and wintered at Deer Creek Station, on the Platte River in central Wyoming.

The expedition recommenced its explorations in May 1860. Raynolds led a party north and west up the upstream portion of the Bighorn River, which is today called the Wind River, hoping to cross the mountains at Togwotee Pass in the Absaroka Range, a mountain pass known to expedition guide Jim Bridger. Meanwhile, Maynadier led his party back north to the Bighorn River to explore it and its associated tributary streams more thoroughly. The plan was for the two parties to reunite on June 30, 1860, at Three Forks, Montana, so they could make observations of a total solar eclipse forecast for July 18, 1860. Hampered by towering basaltic cliffs and deep snows, Raynolds attempted for over a week to reconnoiter to the top of Togwotee Pass, but was forced south due to the June 30 deadline for reaching Three Forks. Bridger then led the party south over another pass in the northern Wind River Range that Raynolds named Union Pass, to the west of which lay Jackson Hole and the Teton Range. From there the expedition went southwest, crossing the southern Teton Range at Teton Pass and entering Pierre's Hole in present-day Idaho. Though Raynolds and his party managed to get to Three Forks by the scheduled date, Maynadier's party was several days late, which prevented a detachment heading north to observe the solar eclipse. The reunited expedition then headed home, traveling from Fort Benton, Montana, to Fort Union near the Montana-North Dakota border via steamboat. It then journeyed overland to Omaha, Nebraska, where the expedition members were disbanded in October 1860.

Though the Raynolds Expedition was unsuccessful in exploring the region that later became Yellowstone National Park, it was the first federally funded party to enter Jackson Hole and observe the Teton Range. The expedition covered over 2,500 miles (4,000 km) and explored an area of nearly 250,000 square miles (650,000 km2). In a preliminary report sent east in 1859, Raynolds stated that the once-abundant bison were being killed for their hides at such an alarming rate they might soon become extinct. Raynolds's immediate participation in the Civil War, followed by a severe illness, delayed him from presenting his report on the expedition until 1868. Research data and botanical specimens, as well as fossils and geological items that had been collected during the expedition, were sent to the Smithsonian Institution but were not studied in detail until after the war. Much of the artwork created by Hutton and especially Schönborn was lost, though several of Schönborn's chromolithographs appeared in Ferdinand V. Hayden's 1883 report that was submitted after later expeditions.

Raynolds returned to Washington at the outbreak of the war, and was made chief topographic engineer of the Department of Virginia in July 1861. The army lacked adequate maps for military use, so Raynolds and his team of engineers began to survey and draw up maps of Virginia and the region of the western portion of that state that had remained loyal to the Union and would become the new state of West Virginia. In 1862, Raynolds was engaged with John C. Frémont's Mountain Department in chasing Stonewall Jackson up the Shenandoah Valley and participated in the Battle of Cross Keys.

Raynolds spent two months recovering from illness after the Valley Campaign, then was assigned as chief engineer of Middle Department and VIII Corps in January 1863. Promoted to major in the Corps of Engineers, he found himself in charge of the defenses of vital Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in March 1863 during Robert E. Lee's second Confederate invasion of the north during the Gettysburg Campaign. On March 31, 1863, the Corps of Topographical Engineers ceased to be an independent branch of the army and was merged into the Corps of Engineers and Raynolds served in that branch of the army for the rest of his career. Officers from the two corps maintained their ranks based on the time at which they received their promotion.

As the end of war approached and hostilities with the Sioux Indians loomed, Raynolds's knowledge of and experiences in the Great Lakes region became more important to the army than his command of the fortifications of Harpers Ferry. As a result, he returned to the Great Lakes as superintending engineer of surveys and lighthouses in April 1864, and saw no further combat for the rest of his career. Before the war was over, on March 13, 1865, Raynolds was brevetted to brigadier general for meritorious service.

After the Civil War, the Corps of Engineers undertook a program of river and harbor improvements. Raynolds supervised the dredging and improvement of navigation on the Arkansas, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. He also helped supervise several harbor dredging and construction projects, involving the harbor in Buffalo, New York, the Harbor of Refuge in New Buffalo, Michigan, Erie Harbor in Erie, Pennsylvania, and the river harbors of St. Louis, Missouri and Alton, Illinois. Raynolds sited and oversaw the installation of dozens of lighthouses in the Great Lakes area, where he served as the superintending engineer from 1864 to 1870. Raynolds was promoted to permanent rank of lieutenant colonel in the Corps of Engineers on March 7, 1867. He then supervised lighthouse construction along the Gulf Coast and in New Jersey where he managed the construction of the Hereford Inlet Lighthouse in 1874.

In 1870, work on the harbors received a boost when the Office of Western River Improvements relocated from Cincinnati, Ohio, to St. Louis with the reassignment of Lt. Col. Raynolds as officer in charge. Since the 1830s, the work of the Office of Western River Improvements had been divided between the Ohio River on one hand and Mississippi, Arkansas, Red, and Missouri rivers on the other. In practice, engineer officers in the Corps of Topographical Engineers maintained temporary offices near each project to oversee work, including one in St. Louis or Alton. After the Civil War and the reunification of the Topographical Engineers and Corps of Engineers, there were separate offices overseeing work on the Ohio River and Western Rivers, each reporting separately to the Chief of Engineers. Most of this work remained snag removal, for which the Corps had built numerous snag-removal vessels. It was only logical to relocate the office closer to the projects being managed by moving the Office of Ohio River Improvements to Cincinnati and Western River Improvements to St. Louis. This was, in essence, the first step taken from a project-based Corps office in St. Louis to what became a district office overseeing regional projects. By 1872, Raynolds was reporting from the Engineer Office in St. Louis with responsibility from the Illinois to the Ohio River rather than from the Office of Western River Improvements, which had ceased to exist.

From May 5 to October 7, 1877, Raynolds led a procession of American engineers to an engineering conference in Europe. Promoted to the permanent rank of colonel on January 2, 1881, Raynolds continued serving with the Corps of Engineers supporting a variety of harbor and river navigational improvements until his retirement in 1884, after a military career spanning forty years. As he approached retirement, Raynolds was elected a trustee of the Presbyterian Church. According to West Point classmate Joseph Reynolds, who saw him at the West Point graduates' reunion in 1893, Raynolds maintained a vigorous and healthy appearance long after his retirement, his brown hair, "then but slightly sprinkled with gray". Raynolds died on October 18, 1894 in Detroit, Michigan, leaving his widow a substantial estate for the time, estimated at between US$50,000 ($1,628,600 today) and $100,000 ($3,257,200 today). After providing for his widow, his will directed that after her death, the entire estate would be donated to the Presbyterian Church. Raynolds was interred in West Lawn Cemetery in Canton, Ohio.