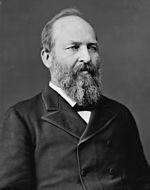

James A. Garfield

James A. Garfield was born in Moreland Hills, Ohio, United States on November 19th, 1831 and is the US President. At the age of 49, James A. Garfield biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 49 years old, James A. Garfield physical status not available right now. We will update James A. Garfield's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Garfield attended Geauga Seminary from 1848 to 1850 and learned academic subjects for which he had not previously had time. He excelled as a student and was especially interested in languages and elocution. He began to appreciate the power a speaker had over an audience, writing that the speaker's platform "creates some excitement. I love agitation and investigation and glory in defending unpopular truth against popular error." Geauga was coeducational, and Garfield was attracted to one of his classmates, Lucretia Rudolph, whom he later married. To support himself at Geauga, he worked as a carpenter's assistant and teacher. The need to go from town to town to find work as a teacher aggravated Garfield, and he developed a dislike of what he called "place-seeking", which became, he said, "the law of my life." In later years, he astounded his friends by disregarding positions that could have been his with little politicking. Garfield had attended church more to please his mother than to worship God, but in his late teens he underwent a religious awakening. He attended many camp meetings, which led to his being born again on March 4, 1850, when he was baptized into Christ by being submerged in the icy waters of the Chagrin River.

After he left Geauga, Garfield worked for a year at various jobs, including teaching jobs. Finding that some New Englanders worked their way through college, Garfield determined to do the same and sought a school that could prepare him for the entrance examinations. From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, a school run by the Disciples. While there, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin, but was inclined to learn about and discuss any new thing he encountered. Securing a position on entry as janitor, he obtained a teaching position while he was still a student there. Lucretia Rudolph also enrolled at the Institute and Garfield wooed her while teaching her Greek. He developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches and, in some cases, earned one gold dollar per service. By 1854, Garfield had learned all the Institute could teach him and was a full-time teacher. Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, as a third-year student; he received credit for two years' study at the Institute after passing a cursory examination. Garfield was also impressed with the college president, Mark Hopkins, who had responded warmly to Garfield's letter inquiring about admission. He said of Hopkins, "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other." Hopkins later said of Garfield in his student days, "There was a large general capacity applicable to any subject. There was no pretense of genius, or alternation of spasmodic effort, but a satisfactory accomplishment in all directions." After his first term, Garfield was hired to teach penmanship to the students of nearby Pownal, Vermont, a post Chester A. Arthur previously held.

Garfield graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Williams in August 1856, was named salutatorian, and spoke at the commencement. His biographer Ira Rutkow writes that Garfield's years at Williams gave him the opportunity to know and respect those of different social backgrounds, and that, despite his origin as an unsophisticated Westerner, socially conscious New Englanders liked and respected him. "In short," Rutkow writes, "Garfield had an extensive and positive first experience with the world outside the Western Reserve of Ohio."

Upon his return to Ohio, the degree from a prestigious Eastern college made Garfield a man of distinction. He returned to Hiram to teach at the Institute and in 1857 was made its principal, though he did not see education as a field that would realize his full potential. The abolitionist atmosphere at Williams had enlightened him politically, after which he began to consider politics as a career. He campaigned for Republican John C. Frémont in 1856. In 1858, he married Lucretia and they had seven children, five of whom survived infancy. Soon after the wedding, he registered to read law at the office of attorney Albert Gallatin Riddle in Cleveland, though he did his studying in Hiram. He was admitted to the bar in 1861.

Local Republican leaders invited Garfield to enter politics upon the death of Cyrus Prentiss, the presumptive nominee for the local state senate seat. He was nominated at the party convention on the sixth ballot and was elected, serving from 1860 to 1861. Garfield's major effort in the state senate was an unsuccessful bill providing for Ohio's first geological survey to measure its mineral resources.

Congressional career

While he served in the Army in early 1862, friends of Garfield approached him about running for Congress from Ohio's newly redrawn and heavily Republican 19th district. He worried that he and other state-appointed generals would receive obscure assignments and running for Congress would allow him to resume his political career. That the new Congress would not hold its first regular session until December 1863 allowed him to continue his war service for a time. Home on medical leave, he refused to campaign for the nomination, leaving that to political managers who secured it at the local convention in September 1862 on the eighth ballot. In the October general election, he defeated D.B. Woods by a two-to-one margin for a seat in the 38th Congress.

Days before his Congressional term began, Garfield lost his eldest daughter, three-year-old Eliza, and became anxious and conflicted, saying his "desolation of heart" might require his return to "the wild life of the army." He also assumed that the war would end before his joining the House, but it had not, and he felt strongly that he belonged in the field, rather than in Congress. He also thought he could expect a favorable command, so he decided to see President Lincoln. During their meeting, Lincoln recommended he take his House seat, as there was an excess of generals and a shortage of administration congressmen, especially those with knowledge of military affairs. Garfield accepted this recommendation and resigned his military commission to do so.

Garfield met and befriended Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, who saw Garfield as a younger version of himself. The two agreed politically and both were part of the Radical wing of the Republican Party. Once he took his seat in December 1863, Garfield was frustrated at Lincoln's reluctance to press the South hard. Many radicals, led in the House by Pennsylvania's Thaddeus Stevens, wanted rebel-owned lands confiscated, but Lincoln threatened to veto any bill that proposed to do so on a widespread basis. In debate on the House floor, Garfield supported such legislation and, discussing England's Glorious Revolution, hinted that Lincoln might be thrown out of office for resisting it. Garfield had supported Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and marveled at the "strange phenomenon in the world's history, when a second-rate Illinois lawyer is the instrument to utter words which shall form an epoch memorable in all future ages."

Garfield not only favored the abolition of slavery, but also believed the leaders of the rebellion had forfeited their constitutional rights. He supported the confiscation of Southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders as a means to ensure a permanent end to slavery. Garfield felt Congress had an obligation "to determine what legislation is necessary to secure equal justice to all loyal persons, without regard to color." He was more supportive of Lincoln when he took action against slavery.

Garfield showed leadership early in his congressional career; he was initially the only Republican vote to terminate the use of bounties in military recruiting. Some financially able recruits had used the bounty system to buy their way out of service (called commutation), which Garfield considered reprehensible. He gave a speech pointing out the flaws in the existing conscription law: 300,000 recruits had been called upon to enlist, but barely 10,000 had done so, with the remainder claiming exemption, providing money, or recruiting a substitute. Lincoln appeared before the Military Affairs committee on which Garfield served, demanding a more effective bill; even if it cost him reelection, Lincoln was confident he could win the war before his term expired. After many false starts, Garfield, with Lincoln's support, procured the passage of a conscription bill that excluded commutation.

Under Chase's influence, Garfield became a staunch proponent of a dollar backed by a gold standard, and strongly opposed the "greenback". He also accepted the necessity of suspension of payment in gold or silver during the Civil War with strong reluctance. He voted with the Radical Republicans in passing the Wade–Davis Bill, designed to give Congress more authority over Reconstruction, but Lincoln defeated it with a pocket veto.

Garfield did not consider Lincoln very worthy of reelection, but there seemed to be no viable alternative. "He will probably be the man, though I think we could do better", he said. Garfield attended the party convention and promoted Rosecrans as Lincoln's running mate, but delegates chose Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson. Lincoln was reelected, as was Garfield. By then, Chase had left the Cabinet and been appointed Chief Justice, and his relations with Garfield became more distant.

Garfield took up the practice of law in 1865 to improve his personal finances. His efforts took him to Wall Street where, the day after Lincoln's assassination, a riotous crowd drew him into an impromptu speech to calm their passions: "Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!" The speech, with no mention or praise of Lincoln, was, according to Garfield biographer Robert G. Caldwell, "quite as significant for what it did not contain as for what it did." In the following years, Garfield had more praise for Lincoln; a year after Lincoln's death, Garfield said, "Greatest among all these developments were the character and fame of Abraham Lincoln," and in 1878 he called Lincoln "one of the few great rulers whose wisdom increased with his power".

Garfield supported black suffrage as firmly as he supported abolition. President Johnson sought the rapid restoration of the Southern states during the months between his accession and the meeting of Congress in December 1865; Garfield hesitantly supported this policy as an experiment. Johnson, an old friend, sought Garfield's backing and their conversations led Garfield to assume Johnson's differences with Congress were not large. When Congress assembled in December (to Johnson's chagrin, without the elected representatives of the Southern states, who were excluded), Garfield urged conciliation on his colleagues, although he feared that Johnson, a former Democrat, might join other Democrats to gain political control. Garfield foresaw conflict even before February 1866, when Johnson vetoed a bill to extend the life of the Freedmen's Bureau, charged with aiding the former slaves. By April, Garfield had concluded that Johnson was either "crazy or drunk with opium."

The conflict between Congress and President Johnson was the major issue of the 1866 campaign, with Johnson taking to the campaign trail in a Swing Around the Circle and Garfield facing opposition within the Republican party in his home district. With the South still disenfranchised and Northern public opinion behind the Republicans, they gained a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress. Garfield, having overcome his challengers at the district nominating convention, won reelection easily.

Garfield opposed the proposed impeachment of Johnson initially when Congress convened in December 1866, but supported legislation to limit Johnson's powers, such as the Tenure of Office Act, which restricted Johnson's ability to remove presidential appointees. Distracted by committee duties, Garfield spoke about these bills rarely, but was a loyal Republican vote against Johnson.

On January 7, 1867, Garfield voted in support of the resolution that launched the first impeachment inquiry against Johnson (run by the House Committee on the Judiciary). On December 7, 1867, he voted against the unsuccessful resolution to impeach Johnson that the House Committee on the Judiciary had sent the full House. On January 27, 1868, he voted to pass the resolution that authorized the second impeachment inquiry against Johnson (run by the House Select Committee on Reconstruction). Due to a court case, he was absent on February 24, 1868, when the House impeached Johnson, but gave a speech aligning himself with Thaddeus Stevens and others who sought Johnson's removal shortly thereafter. Garfield was present on March 2 and 3, 1868, when the House voted on specific articles of impeachment, and voted in support of all 11 articles. During the March 2 debate on the articles, Garfield argued that what he characterized as Johnson's attempts to render Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and William H. Emory personal tools of his demonstrated Johnson's intent to disregard the law and override the Constitution, suggesting that Johnson's trial perhaps could be expedited to last only a day in order to hasten his removal. When Johnson was acquitted in his trial before the Senate, Garfield was shocked and blamed the outcome on the trial's presiding officer, Chief Justice Chase, his onetime mentor.

By the time Grant succeeded Johnson in 1869, Garfield had moved away from the remaining radicals (Stevens, their leader, had died in 1868). He hailed the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870 as a triumph and favored Georgia's readmission to the Union as a matter of right, not politics. In 1871, Congress took up the Ku Klux Klan Act, which was designed to combat attacks on African Americans' suffrage rights. Garfield opposed the act, saying, "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation." He was torn between his indignation at the Klan, whom he called "terrorists", and his concern for the power given the president to enforce the act through suspension of habeas corpus.

Throughout his political career, Garfield favored the gold standard and decried attempts to increase the money supply through the issuance of paper money not backed by gold, and later, through the free and unlimited coinage of silver. In 1865, he was placed on the House Ways and Means Committee, a long-awaited opportunity to focus on financial and economic issues. He reprised his opposition to the greenback, saying, "Any party which commits itself to paper money will go down amid the general disaster, covered with the curses of a ruined people." In 1868 Garfield gave a two-hour speech on currency in the House, which was widely applauded as his best oratory to that point; in it he advocated a gradual resumption of specie payments, that is, the government paying out silver and gold, rather than paper money that could not be redeemed.

Tariffs had been raised to high levels during the Civil War. Afterward, Garfield, who made a close study of financial affairs, advocated moving toward free trade, though the standard Republican position was a protective tariff that would allow American industries to grow. This break with his party likely cost him his place on the Ways and Means Committee in 1867, and though Republicans held the majority in the House until 1875, Garfield remained off that committee. Garfield came to chair the powerful House Appropriations Committee, but it was Ways and Means, with its influence over fiscal policy, that he really wanted to lead. One reason he was denied a place on Ways and Means was the opposition of the influential Republican editor Horace Greeley.

In September 1870, Garfield, then chairman of the House Banking Committee, led an investigation into the Black Friday Gold Panic scandal. The investigation was thorough, but found no indictable offenses. Garfield thought the scandal was enabled by the greenbacks that financed the speculation.

Garfield was not at all enthused about President Grant's reelection in 1872—until Greeley, who emerged as the candidate of the Democrats and Liberal Republicans, became the only serious alternative. Garfield said, "I would say Grant was not fit to be nominated and Greeley is not fit to be elected." Both Grant and Garfield were overwhelmingly reelected.

The Crédit Mobilier of America scandal involved corruption in the financing of the Union Pacific Railroad, part of the transcontinental railroad which was completed in 1869. Union Pacific officers and directors secretly purchased control of the Crédit Mobilier of America company, then contracted with it to undertake construction of the railroad. The railroad paid the company's grossly inflated invoices with federal funds appropriated to subsidize the project, and the company was allowed to purchase Union Pacific securities at par value, well below the market rate. Crédit Mobilier showed large profits and stock gains, and distributed substantial dividends. The high expenses meant Congress was called upon to appropriate more funds. One of the railroad officials who controlled Crédit Mobilier was also a congressman, Oakes Ames of Massachusetts. He offered some of his colleagues the opportunity to buy Crédit Mobilier stock at par value, well below what it sold for on the market, and the railroad got its additional appropriations.

The story broke in July 1872, in the middle of the presidential campaign. Among those named were Vice President Schuyler Colfax, Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson (the Republican candidate for vice president), Speaker James G. Blaine of Maine, and Garfield. Greeley had little luck taking advantage of the scandal. When Congress reconvened after the election, Blaine, seeking to clear his name, demanded a House investigation. Evidence before the special committee exonerated Blaine. Garfield had said in September 1872 that Ames had offered him stock but he had repeatedly refused it. Testifying before the committee in January, Ames said he had offered Garfield ten shares of stock at par value, but that Garfield had never taken them or paid for them, though a year passed, from 1867 to 1868, before Garfield had finally refused. Appearing before the committee on January 14, 1873, Garfield confirmed much of this. Ames testified several weeks later that Garfield agreed to take the stock on credit, and that it was paid for by the company's huge dividends. The two men differed over $300 that Garfield received and later paid back, with Garfield deeming it a loan and Ames a dividend.

Garfield's biographers have been unwilling to exonerate him in the scandal. Allan Peskin writes, "Did Garfield lie? Not exactly. Did he tell the truth? Not completely. Was he corrupted? Not really. Even Garfield's enemies never claimed that his involvement in the affair influenced his behavior." Rutkow writes, "Garfield's real offense was that he knowingly denied to the House investigating committee that he had agreed to accept the stock and that he had also received a dividend of $329." Caldwell suggests Garfield "told the truth [before the committee, but] certainly failed to tell the whole truth, clearly evading an answer to certain vital questions and thus giving the impression of worse faults than those of which he was guilty." That Crédit Mobilier was a corrupt organization had been a badly kept secret, even mentioned on the floor of Congress, and editor Sam Bowles wrote at the time that Garfield, in his positions on committees dealing with finance, "had no more right to be ignorant in a matter of such grave importance as this, than the sentinel has to snore on his post."

Another issue that caused Garfield trouble in his 1874 reelection bid was the so-called "Salary Grab" of 1873, which increased the compensation for members of Congress by 50%, retroactive to 1871. As chairman of the Appropriations Committee, Garfield was responsible for shepherding the appropriations bill through the House; during the debate in February 1873, Massachusetts Representative Benjamin Butler offered the increase as an amendment, and despite Garfield's opposition, it passed the House and eventually became law. The law was very popular in the House, as almost half the members were lame ducks, but the public was outraged, and many of Garfield's constituents blamed him, though he personally refused to accept the increase. In a bad year for Republicans, who lost control of the House for the first time since the Civil War, Garfield had his closest congressional election, winning with only 57% of the vote.

The Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives in 1875 meant the loss of Garfield's chairmanship of the Appropriations Committee, though the Democrats did put him on the Ways and Means Committee. With many of his leadership rivals defeated in the 1874 Democratic landslide, and Blaine elected to the Senate, Garfield was seen as the Republican floor leader, and the likely Speaker, should the party regain control of the chamber.

Garfield thought the land grants given to expanding railroads was an unjust practice. He also opposed monopolistic practices by corporations, as well as the power sought by workers' unions. He supported the proposed establishment of the United States civil service as a means of ridding officials of the annoyance of aggressive office seekers. He especially wished to eliminate the practice of forcing government workers, in exchange for their positions, to kick back a percentage of their wages as political contributions.

As the 1876 presidential election approached, Garfield was loyal to the candidacy of Senator Blaine, and fought for the former Speaker's nomination at the 1876 Republican National Convention in Cincinnati. When it became clear, after six ballots, that Blaine could not prevail, the convention nominated Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes. Although Garfield had supported Blaine, he had kept good relations with Hayes, and wholeheartedly supported the governor. Garfield had hoped to retire from politics after his term expired to devote himself full-time to the practice of law, but to help his party, he sought re-election, and won it easily that October. Any celebration was short-lived, as Garfield's youngest son, Neddie, fell ill with whooping cough shortly after the congressional election, and soon died.

When Hayes appeared to have lost the presidential election the following month to Democrat Samuel Tilden, the Republicans launched efforts to reverse the results in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, where they held the governorship. If Hayes won all three states, he would take the election by a single electoral vote. Grant asked Garfield to serve as a "neutral observer" of the recount in Louisiana. The observers soon recommended to the state electoral commissions that Hayes be declared the winner—Garfield recommended the entire vote of West Feliciana Parish, which had given Tilden a sizable majority, be thrown out. The Republican governors of the three states certified that Hayes had won their states, to the outrage of Democrats, who had the state legislatures submit rival returns, and threatened to prevent the counting of the electoral vote—under the Constitution, Congress is the final arbiter of the election. Congress then established an Electoral Commission, consisting of eight Republicans and seven Democrats, to determine the winner. Despite his objection to the Commission, Garfield was appointed to it. He felt Congress should count the vote and proclaim Hayes victorious. Hayes emerged the victor by a party line vote of 8–7. In exchange for recognizing Hayes as president, Southern Democrats secured the removal of federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction.

Although an Ohio Senate seat would be vacated by the resignation of John Sherman to become Treasury Secretary, Hayes needed Garfield's expertise to protect him from the agenda of a hostile Congress, and asked him not to seek it. Garfield agreed. As Hayes's key legislator in the House, he gained considerable prestige and respect for his role there. When Congress debated the Bland–Allison Act, to have the government purchase large quantities of silver and strike it into legal tender dollar coins, Garfield opposed it as a deviation from the gold standard; it was enacted over Hayes's veto in February 1878.

In 1876, Garfield purchased the property in Mentor that reporters later dubbed Lawnfield, where he conducted the first successful front porch campaign for the presidency. Hayes suggested that Garfield run for governor in 1879, seeing that as a road likely to take Garfield to the White House. Garfield preferred to seek election as a U.S. senator. Rivals were spoken of for the seat, such as Secretary Sherman, but he had presidential ambitions (for which he sought Garfield's support), and other candidates fell by the wayside. The General Assembly elected Garfield to the Senate in January 1880, though his term was not scheduled to commence until March 4, 1881. Garfield was never seated in the U.S. Senate.

In 1865, Garfield became a partner in the law firm of a fellow Disciple of Christ, Jeremiah Black. They had much in common, except politics: Black was an avid Democrat, having served in the cabinet of President James Buchanan. The next year, Black was retained by some pro-Confederate northern civilians who had been found guilty of treason in a military court and sentenced to death. Black saw an opportunity to strike a blow against military courts and the Republicans. He had heard Garfield's military speeches, and learned of not only his oratory skills but also his resistance to expansive powers of military commissions. Black assigned the case to Garfield one week before arguments were to be made before the U. S. Supreme Court. When Black warned him of the political peril, Garfield responded, "It don't make any difference. I believe in English liberty and English law." In this landmark case, Ex parte Milligan, Garfield successfully argued that civilians could not be tried before military tribunals, despite a declaration of martial law, as long as civil courts were still operating. In his very first court appearance, Garfield's oral argument lasted over two hours, and though his wealthy clients refused to pay him, he had established himself as a preeminent lawyer.

During Grant's first term, Garfield was discontented with public service and in 1872 again pursued opportunities in the law. But he declined a partnership offer from a Cleveland law firm when told his prospective partner was of "intemperate and licentious" reputation. In 1873, after Chase's death, Garfield appealed to Grant to appoint Justice Noah H. Swayne Chief Justice, but Grant appointed Morrison R. Waite.

In 1871, Garfield traveled to Montana Territory to negotiate the removal of the Bitterroot Salish tribe to the Flathead Indian Reservation. Having been told that the people would happily move, Garfield expected an easy task. Instead, he found the Salish determined to stay in their Bitterroot Valley homeland. His attempts to coerce Chief Charlo to sign the agreement nearly brought about a military clash. In the end, he convinced two subchiefs to sign and move to the reservation with a few of the Salish people. Garfield never convinced Charlo to sign, although the official treaty document voted on by Congress bore his forged mark.

In 1876, Garfield developed a trapezoid proof of the Pythagorean theorem, which was published in the New England Journal of Education. Mathematics historian William Dunham wrote that Garfield's trapezoid work was "really a very clever proof." According to the Journal, Garfield arrived at the proof "in mathematical amusements and discussions with other members of congress."

After his conversion experience in 1850, religious inquiry was a high priority for Garfield. He read widely and moved beyond the confines of his early experience as a member of the Disciples of Christ. His new, broader perspective was rooted in his devotion to freedom of inquiry and his study of history. The intensity of Garfield's religious thought was also influenced by his experience in combat and his interaction with voters.