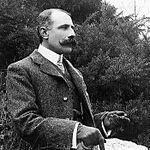

Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar was born in Broadheath, England, United Kingdom on June 2nd, 1857 and is the Composer. At the age of 76, Edward Elgar biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 76 years old, Edward Elgar has this physical status:

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (1857–1934), was an English composer whose works have appeared in the British and international classical concert repertoire.

Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works by Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, concertos for violin and cello, and two symphonies.

In addition, he composed The Dream of Gerontius, chamber music, and songs.

In 1924, he was appointed Master of the King's Musick. Although Elgar is often thought of as a traditional English composer, the bulk of his musical influences came from continental Europe, not England.

He felt himself to be an outsider, not just technically, but also socially.

He was a self-taught composer in academic circles, and in Protestant Britain, his Roman Catholicism was regarded with suspicion in some quarters; and in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, he was acutely aware of his humble roots long before he gained prominence.

Despite this, he married the daughter of a senior British army officer.

She inspired him both musically and socially, but he didn't succeed until his forties, when his Enigma Variations (1899) became extremely popular in Britain and elsewhere.

He continued the Variations with a choral work The Dream of Gerontius (1900), based on a Roman Catholic text that sparked some disquiet in the Anglican institution in the United Kingdom, but it has since been based on a Roman Catholic text that has inspired some fear in the Anglican establishment in Britain, but it has been and has remained a main repertory work in Britain and elsewhere.

His later full-length choral works were well-received, but no one has appeared in the regular repertory. Elgar wrote a symphony and a violin concerto that were highly popular in his fifties.

His second symphony and cello concerto did not immediately gain attention in the concert repertory of British orchestras, and it took many years for him to earn a regular place in British orchestras.

Elgar's music began in his later years to be seen as particularly appealing to British audiences.

His stock remained poor a decade after his death.

It began to recover strongly in the 1960s, aided by new recordings of his works.

Some of his works have been performed internationally in recent years, but the music continues to be more popular in Britain than elsewhere. Elgar has been dubbed the first composer to take the gramophone seriously.

He made a series of acoustic recordings of his works between 1914 and 1925.

The introduction of the moving-coil microphone in 1923 made a much more accurate sound reproduction possible, and Elgar released new recordings of the majority of his major orchestral works and excerpts from The Dream of Gerontius.

Early years

Edward Elgar was born in Lower Broadheath, just south of Worcester, England, on June 2nd, 1857. William Henry Elgar (1821–1906) was born in Dover and had been apprenticed to a London music publisher. William moved to Worcester, England, in 1841, where he worked as a piano tuner and opened a shop that sold sheet music and musical instruments. Ann Greening (1822-1902), the daughter of a farm labourer, married him in 1848. Edward was the fourth of their seven children. Ann Elgar had converted to Roman Catholicism shortly before Edward's birth, and he was baptized and brought up as a Roman Catholic to his father's disapproval. William Elgar, a violinist of a professional calibre, served as organist of St George's Roman Catholic Church, Worcester, Worcester, from 1846 to 1885. Masses by Cherubini and Hummel were first performed by the orchestra in which he appeared at the Three Choirs Festival at his instigation. All Elgar children were educated by a musical system. By the age of eight, Elgar was taking piano and violin lessons, and his father, who tuned the pianos at many grand houses in Worcestershire, would occasionally take him along, giving him the opportunity to showcase his talent to local celebrities.

Elgar's mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical growth. He inherited a keen eye for literature as well as a deep love of the countryside from her. Elgar's early influences, according to his friend and biographer W. H. "Billy" Reed, "permeated all his work and extended his life in a subtle but strong English manner." He began writing at an early age; when he was about ten, he wrote music and performed with the Elgar children; forty years later, he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites were titled The Wand of Youth.

Elgar did not have a general education at Littleton (now Lyttleton) House School, near Worcester, before he was fifteen years old. During brief visits to London in 1877–78, Adolf Pollitzer's only formal musical instruction outside of piano and violin lessons from local teachers consisted of more advanced violin studies. "My first music was learned in the Cathedral," Elgar said, "not as many as ten" in the time, whether I was eight, nine, or ten." He read every book he could find on the theory of music from manuals of organ playing and read every book on the theory of music. He later said that Hubert Parry's articles in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians had helped him greatly. Elgar began learning German in the hopes of furthering musical study at the Leipzig Conservatory, but his father could not afford to send him. "The budding composer had to escape the schools' dogmatism," a review in The Musical Times said years later. However, it was a disappointment to Elgar that after leaving school in 1872, he went not to Leipzig but to the office of a local solicitor as a clerk. He didn't find an office job that fulfilled, and for pleasure, he turned not only to music but also to literature, becoming a voracious reader. He made his first public appearances as a violinist and organist around this time.

Elgar left the solicitor after a few months to pursue a career in music, teaching piano and violin lessons and occasionally in his father's shop. He and his father, who accompanied musicians, performed the violin, composed and arranged performances, and performed for the first time. Elgar, according to Pollitzer, had the potential to be one of the country's best soloists, but Elgar himself, who had heard leading virtuosi, felt his own violin playing was lacking a full enough tone, and he abandoned his aspirations to be a soloist. He took up the post of conductor of the attendants' band at the Worcester and County Lunatic Asylum, three miles (five kilometers) from Worcester at twenty-two. The band consisted of piccolo, flute, clarinet, two corks, euphonium, three or four first violins, occasional viola, cello, and piano. Elgar coached the players and arranged their music, including quadrilles and polkas, for the unusual combination of instruments. "This practical knowledge proved to be of the greatest benefit to the young musician," the Musical Times said. ... He acquired a practical knowledge of these various devices. ... He's now got to know very well the tone color, the ins and outs of these and other devices. He wrote for five years, from 1879 to Powick once a week. Professor of the violin at the Worcester College for the Blind Sons of Gentlemen was another post he held in his youth.

Elgar flourished in Worcester's musical circles, although rather solitary and reflective by nature. He appeared in the violins at the Worcester and Birmingham Festivals, and one of his favorites was to perform Dvov's Symphony No. 61. Stabat Mater under the composer's baton. Elgar played the bassoon in a wind quintet, as well as his brother Frank, an oboist (and conductor) who performed his own wind band. Elgar arranged many works by Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, and others for the quintet, honed in his arrangement and compositional skills.

Elgar's first trips abroad, he visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Samans play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. "I got really dosed with Schumann in 1882 (my dream! ) So had no reason to be concerned, so Brahms, Rubinstein, & Wagner had no reason to complain." He visited Helen Weaver, a Conservatoire student, in Leipzig. They became involved in the summer of 1883, but the engagement was postponed the next year due to unknown reasons. Elgar was greatly distraught, and some of his later cryptic devotions of romantic music may have related to Helen and his feelings for her. Elgar was often inspired by close women friends,; Helen Weaver was followed by Mary Lygon, Dora Penny, Julia Worthington, Alice Stuart Wortley, and eventually Vera Hockman, who enlived his old age.

Elgar, a violinist in Birmingham, was hired as a violinist in William Stockley's Orchestra in 1882, for whom he appeared at every concert for the next seven years and where he later said he "learned all the music I knew." He appeared at Birmingham Town Hall on December 13, 1883, the first time one of his first works for full orchestra, the Sérénade mauresque, was performed by a professional orchestra for the first time. Stockley had invited him to conduct the piece but then discovered "he disdiyed" and, in the meantime, insisted on remaining in his place in the orchestra. The result was that he had to appear, fiddle in hand, to honor the audience's genuine and hearty applause." Elgar used to London to get his books published, but this time in his life saw him frequently dissatisfied and low on funds. "My prospects are about as hopeless as ever," he wrote to a friend in April 1884. I am not interested in energy, so sometimes I come to the conclusion that I have a 'tis want of what's lacking.' ... I have no money, not a single cent."

When Elgar was 29, he took on Alice Roberts, daughter of late Major-General Sir Henry Roberts, and published author of verse and prose fiction. Alice married Elgar three years later. Elgar was eight years older than Elgar. "Alice's family was horrified by her decision to marry an unknown artist who worked in a store and was a Roman Catholic," Elgar's biographer Michael Kennedy writes. She was "disinherited." They were married in Brompton Oratory on May 8th, 1889. She served as both his company chief and social secretary from then onwards, and she was a perceptive musician critic. She tried to get him the attention of a wealthy society, but it was met with little success. He'll grow to accept the awards he received in time, knowing that they were more to her and her social class than they were to her, and her social class, and acknowledging what she had sacrificed to advance his career. "The care of a genius is enough of a life work for any woman," she wrote in her diary. Elgar dedicated his short violin-and-piano piece Salut d'Amour to her as an engagement presenter. The Elgars moved to London to be closer to the center of British musical life with Alice's support, and Elgar started devoting his time to composition. Carice Irene, their sole child, was born in West Kensington on August 14th, 1890. Her name, which was revealed in Elgar's dedication to Salut d'Amour, was a diminution of her mother's names Caroline and Alice.

Elgar made the most of the opportunity to hear new music. It was not possible for young composers to get to know new music in the days before miniature scores and albums were released. Elgar had every chance to perform at the Crystal Palace concerts. He and Alice listened to music by a diverse range of composers the day after. Berlioz and Richard Wagner were among these masters of orchestration from whom he learned a great deal, including Berlioz and Richard Wagner. His own compositions had no effect on London's musical scene. The orchestral version of Salut d'amour and the Suite in D at the Crystal Palace in Washington was conducted by August Manns, and two publishers have accepted Elgar's violin works, organ voluntaries, and part songs. Any tantalizing opportunities appeared to be within reach, but then abruptly, they were gone. For example, an invitation from the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, to perform some of his pieces was refused at the last second when Sir Arthur Sullivan arrived unannounced to rehearse some of his own composition. When Elgar later told him what had happened, Sullivan was shocked. Elgar's only significant commission while in London came from his hometown: the Worcester Festival Committee invited him to create a short orchestral work for the 1890 Three Choirs Festival. "His first major work, the assured and uninhibited Froissart," Diana McVeagh of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians says. In September 1890, Elgar gave his first appearance in Worcester. He was forced to leave London in 1891 and return with his wife and child to Worcestershire, where he could make a living teaching local musical ensembles and teaching. They settled in Great Malvern, Alice's former home town.

Elgar gradually established a reputation as a composer in the English Midlands, chiefly because of his appearances at the great choral festivals. The Black Knight (1892) and King Olaf (1896), both inspired by Longfellow's The Light of Life (1896) and Caractacus (1898), were modestly successful, and he acquired a long-serving publisher in Novello and Co. Elgar was of enough fame locally to recommend Samuel Coleridge-Taylor to the Three Choirs Festival for a concert piece that helped kickstart the younger man's career. Elgar was drobbing for the attention of renowned commentators, but their reviews were more polite than ardent. Despite being in demand as a festival conductor, he was only getting by financially and felt unappreciated. He was "very sick at heart about music" in 1898 and wanted to find a way to be successful with a larger audience. August Jaeger, his friend, continued to lift his spirits: "A day's assault of the blues would not drive away your desire, your desire, or your ability, which is to exercise your creative abilities that a kind providence has given you." It's time to be universal recognition."

That prediction came true in 1899. Elgar created the Enigma Variations, which premiered in London under the baton of eminent German conductor Hans Richter at the age of forty-two. "I have sketched a set of Variations on an original theme," Elgar's own words. The Variations have enthralled me because I've branded them with my specific friends' names — that is, to say, I've written the variations to reflect the personality of the party (the individual)... and I've written what I'd like to write if they were assessing enough to write. "To my family members pictured within," the photographer dedicated the job. The most well-known adaptation is probably "Nimrod," depicting Jaeger. Elgar chose not to eliminate variations depicting Arthur Sullivan and Hubert Parry, whose designs he tried but were unable to include in the variations because of pure musical considerations. The large-scale work was lauded for its ingenuity, charisma, and craftsmanship, and it established Elgar as the pre-eminent British composer of his time.

Variations on an Original Theme is a form of art; the word "Enigma" appears over the first six bars of music, which led to the familiar version of the term. Although there are fourteen variations on the "original theme," Elgar has introduced yet another overarching theme, "runs through and over the entire set," but is never seen. Although Elgar is now known as a uniquely English composer, his orchestral music and this work in particular share a lot with the Central European tradition typified at the time by Richard Strauss' work. The Enigma Variations were well-reced in Germany and Italy, and they are still a worldwide concert staple to this day.

"When Sir Arthur Sullivan died in 1900, it became clear to many that Elgar, although a composer of another builder, was his first musician of the land," Elgar's biographer Basil Maine wrote. Elgar's next big project was eagerly awaited. He performed Cardinal John Newman's poem The Dream of Gerontius for soloists, chorus, and orchestra at the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1900. Richter conducted the premiere, which was marred by a poorly prepared chorus that sang poorly. Despite the piece's shortcomings, critics acknowledged it. It was held in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 1901 and again in 1902, directed by Julius Buths, who also conducted the Enigma Variations' European premiere in 1901. The German press was raving. "In both directions we encounter beauties of imperishable value," the Cologne Gazette said. ... Elgar is based on Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt, who have all been influenced by their influences until he has risen to the point of being a crucial individuality. He is one of the modern times' finest composers. "A memorable and epoch-making debut," the Düsseldorfer Volksblatt wrote. Nothing has been produced in Liszt's oratorio since the days of Liszt, which has the same reverence and awe of this sacred cantata." Richard Strauss, then widely regarded as the best composer of his day, was so captivated that he suggested a toast to the success of "the first English progressive musician, Meister Elgar" in Elgar's presence. Performances in Vienna, Paris, and New York followed, and The Dream of Gerontius followed in Britain shortly. "It is unquestionably the finest British work in the oratorio style," Kennedy said, "it] opened a new chapter in the English choral tradition and freed it from its Handelian preoccupation." Elgar, a Roman Catholic, was greatly moved by Newman's essay about the death and remission of a sinner, but some influential members of the Anglican Church of Anglican disobeyed. Charles Villiers Stanford, his coworker, complained that the job "stinks of incense." Gerontius was banned from his cathedral in 1901, and the Dean of Worcester, a year later, insisted on expurgations before allowing a performance.

Elgar is most well known for the first of the five Pomp and Circumstance Marches, which were built between 1901 and 1930. Every year, millions of television viewers from around the world watch the Last Night of the Proms, where it is traditionally performed. "I've got a tune that'll knock 'em" as the theme of the first march's slower middle section (technically called the "trio") of the first marche came into his head, he told his friend Dora Penny, "I've got a tune that will knock 'em." When the first march was performed in 1901 at a London Promenade Concert, Henry Wood, who later reported that the audience "rose and yelled, the first and only time in Promenade concerts that an orchestral piece was given a double encore." Elgar was hired by Edward VII to set A. C. Benson's Coronation Ode for a gala concert at the Royal Opera House on June 30, 1902. The king's blessing was confirmed, and Elgar began to function. Clara Butt had persuaded him that the three members of the first Pomp and Circumstance march could have terms attached to it, and Elgar encouraged Benson to do so. The new vocal version of Elgar was integrated into the Ode. The score's developers recognized the merits of the vocal piece "Land of Hope and Glory," and asked Benson and Elgar to make a new revision for publication as a separate piece. It was extremely popular and is now considered an unofficial British national anthem. The trio, also known as "Pomp and Circumstance" or "The Graduation March," has been in use in the United States since 1905 for virtually all high school and university graduations.

Elgar's works were on display in Covent Garden in March 1904, an award that never before had been given to an English composer. "If any one had predicted that the Opera-house would be full from floor to ceiling for the performance of an English composer's oratorio would be out of his mind," the Times said. The king and queen attended the first concert, during which Richter performed The Dream of Gerontius, and returned to The Apostles in London for the second time (first heard at the Birmingham Festival the previous year). The final concert of the festival, hosted by Elgar, was mainly orchestral, except for an excerpt from Caractacus and the complete Sea Pictures (sung by Clara Butt). Froissart, Enigma Variations, Cockaigne, the first two marches (at that time the only two) were marched, Circumstance marches, and the premiere of a new orchestral work In the South, inspired by a holiday in Italy.

On July 5, 1904, Elgar was knighted at Buckingham Palace. He and his family lived in Pl's Gwyn, a large house on the outskirts of Hereford, overlooking the River Wye, where they lived until 1911. Elgar was at the zenith of fame between 1902 and 1914, according to Kennedy. He made four visits to the United States, including one conducting a tour, and derived a lot of money from his music's appearance. He served as Peyton Professor of Music at the University of Birmingham from 1905 to 1908. He had reluctantly accepted the article, deciding that a composer should not lead a school of music. He was not at ease in the role, and his lectures caused controversies, particularly on the critics and English music in general: "Vulgarity in the course of time may be refined." The rise of creativity is often associated with ingenuity, but the commonplace mind can never be anything but routine. An Englishman will lead you into a large room, beautifully proportioned, and will tell you that it is white rather than white, and that 'What exquisite taste' will follow. You can tell in your own mind that it is not flavor at all, that it is not taste at all. It is simply evasion. "All English music is white, and it evades everything." He regretted the scandal but was eager to give the post to his friend Granville Bantock in 1908. His new life as a celebrity was a mixed blessing to the wealthy Elgar, as it invaded his privacy and he was often in danger of being in danger of sickness. In 1903, he told Jaeger, "My life is a continuous giving up of little things that I adore." In this decade, both W. S. Gilbert and Thomas Hardy wanted to collaborate with Elgar. Elgar turned down a job but if Shaw had been able to partner with Bernard Shaw, they would have collaborated.

Elgar went to the United States on three separate trips between 1905 and 1911. His first was to perform his music and to graduate with a doctorate from Yale University. The introduction and Allegro for Strings, Samuel Sanford's most popular composition in 1905, was his Introduction and Allegro for Strings. It was well received, but it didn't capture the public's attention, as The Dream of Gerontius had done and continues to do. However, among keen Elgars, the Kingdom was sometimes preferred to earlier work: "Compared to The Kingdom, Gerontius is the work of a raw amateur," Elgar's friend Frank Schuster told the young Adrian Boult. As Elgar's fiftieth birthday approached, he began working on his first symphony, a project that had been on his mind in various forms for nearly ten years. His First Symphony (1908) was a national and international triumph. It was performed in New York under Walter Damrosch, Vienna under Ferdinand Löwe, St Petersburg under Alexander Siloti, and Leipzig under Arthur Nikisch. In Rome, Chicago, Boston, Toronto, and Toronto, fifteen British towns and cities were showcased. It has sold over a hundred performances in Britain, America, and continental Europe in less than a year.

Fritz Kreisler, one of the leading international violinists of the time, commissioned the Violin Concerto (1910). Elgar wrote it during 1910's summer, with occasional assistance from W. H. Reed, the conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, who helped the composer with technical questions. Elgar and Reed developed a strong bond that lasted for the remainder of Elgar's life. Elgar As I Knew Him (1936), Reed's biography, contains numerous elements of Elgar's composition. The Royal Philharmonic Society, with Kreisler and the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer, accompanied the work. "The Concerto proved to be a complete triumph, and the performance was a memorable and memorable experience," Reed said. So much was the effect of the concerto that Kreisler's colleague Eugène Ysa'e spent so much time with Elgar going through the assembly. When Ysa's financial difficulties prevented them from playing it in London, there was a great deal.

The Violin Concerto was Elgar's last big success. He performed his Second Symphony in London the following year, but the audience was dissatisfied with the result. It's not like the First Symphony that it ends in a blaze of orchestral splendour but rather quietly and reflectively. "But I wasn't recalled to the podium multiple times to applaud the applause, and even an English audience, as it was after the Violin Concerto or the First Symphony," Reed, who appeared at the premiere, later said. "What is the deal with them, Billy?" Elgar asked Reed. They look like a lot of stuffed pigs." The performance was, by normal standards, a success, with twenty-seven performances within three years of its premiere, but it did not have the same international fervore as the First Symphony.

Elgar was appointed to the Order of Merit in June 1911 as part of King George V's coronation, an honour that was not restricted to twenty-four holders at any time. The Elgars returned to London in the following year to a large house in Netherhall Gardens, Hampstead, designed by Norman Shaw. Elgar's last two large-scale works of the prewar period, the choral ode, The Music Makers (for the Birmingham Festival, 1912), and the symphonic study Falstaff (for the Leeds Festival, 1913). Both were treated politely but not with enthusiasm. Also the dedicatee of Falstaff, conductor Landon Ronald, confessed openly that he could not "make head or tail of the piece," while music scholar Percy Scholes wrote of Falstaff that it was a "great achievement" but that "a comparative failure" was "as far as public recognition goes."

Elgar was terrified at the prospect of the carnage, but his patriotic feelings were nonetheless heightened. He wrote "A Song for Soldiers" in which he later drew. He began serving as a special constable in the local police and later joined the army's Hampstead Volunteer Reserve. Carillon, a recitation for speaker and orchestra in honor of Belgium, and Polonia, an orchestral work in honour of Poland, was commissioned by him. Land of Hope and Glory, which had been well-known, became more popular, and Elgar wished in vain to have new, less nationalistic, words sung to the tune.

Elgar's other works during the war included incidental music for a children's play, The Starlight Express (1915); a ballet, The Spirit of England (1915), and Laurence Binyon's poems. The Fringes of the Fleet, Rudyard Kipling's setting of verses, gained a lot of attention around the country until Kipling's unethical reasons objected to their performance in theatres. Elgar conducted a video of the Gramophone Company's activity.

Elgar was in poor health at the time of the war. His wife thought it best for him to move to the countryside, and she rented "Brinkwells," a house near Fittleworth, Sussex, from painter Rex Vicat Cole. There Elgar recovered his energy and created four large-scale works between 1918 and 1919. The first three of these were chamber works: the Violin Sonata in E minor, the Piano Quintet in A minor, and the String Quartet in E minor. "E. writing wonderful new music" as she observed the project at work, Alice Elgar wrote in her diary. Both three works were well received. "Elgar's sonata has much more than we've seen in other media," the Times said, "but we don't want him to change and be someone else." On May 21, 1919, the quartet and quintet were first introduced at the Wigmore Hall. "This quartet, with its elquent climaxes, mysterious dance-rhythms, and its seamless symmetry, as well as the magnificent oratorios were of their kind," the Manchester Guardian said.

In comparison, the Cello Concerto in E minor's first season, which was also a failure, at the opening concert of the London Symphony Orchestra's 1919-20 season in October 1919. Apart from the Elgar concert, which was performed by the composer, Albert Coates, who overran his rehearsal time at the expense of Elgar's, was the remainder of the program. "That brutal selfish ill-mannered bounder... that brute Coates kept rehearsing," Lady Elgar wrote. "There have been rumors about during the week of ineffective rehearsal," Ernest Newman, the observer. Whatever the reason, the sad truth is that no orchestra, in all likelihood, has so little orchestra orchestra made such gruesome an exhibition. ...... The work itself is lovely, very simple – the pregnant simplicity that has appeared on Elgar's music in the last two years – but it is veiled with a profound wisdom and beauty under its hood. Felix Salmond, the soloist who did the job for Elgar again later, bore no blame. The Cello Concerto did not have a second performance in London for more than a year, in comparison to the First Symphony and its hundred performances in less than a year.

Although Elgar's music was no longer in style in the 1920s, his followers continued to perform his works as often as possible. Reed selected "a young man almost unknown to the public" for bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to a larger audience in March 1920. Landon Ronald performed an all-Elgar concert at the Queen's Hall in 1920. Alice Elgar wrote ecstatic about the symphony's reception, but this was one of the last times she heard Elgar's music performed in public. She died of lung cancer after a short illness on April 7, 1920, at the age of seventy-two.

The death of his wife devastated Elgar. Alice allowed himself to be deterred from creation with no demand for new works and being deprived of Alice's constant support and inspiration. Elgar's daughter later recalled that he inherited a reluctance to "settle down to work on hand but that he could cheerfully invest hours on a seemingly insignificant and entirely unnecessary venture," a characteristic that grew on Alice's death. Elgar indulged himself in his varied pastimes for the majority of his life. He was an avid amateur chemist throughout his life, with occasional use of a microscope in his back garden. In 1908, he even invented the "Elgar Sulphuretted Hydrogen Apparatus." He loved football, especially Wolverham Wanderers F.C., for whom he composed "He Banged the Leather for Goal," and he continued to attend horse races in later years. Malcolm Sargent, the conductor, and violinist Yehudi Menuhin all recall rehearsals with Elgar, which ended with him expressing himself that all was fine and then moved on to the championships. In his youth, Elgar had been an avid bicycle, acquiring Royal Sunbeam bicycles for himself and his wife in 1903 (he referred to him as "Mr. Phoebus"). He loved being chauffeured around the countryside as an elderly widower. He travelled from Brazil, from the Amazon to Manaus, where the Teatro Amazonas impressed him in November and December 1923. Almost nothing is known about Elgar's life or the events that he lived during the trip, which gave the novelist James Hamilton-Paterson a great deal of authority when writing Gerontius, a fictional account of the journey.

Elgar sold the Hampstead house after Alice's death, and after living in a flat in St James' in the city's heart, he returned to Worcestershire, where he lived from 1923 to 1927. In those years, he did not abandon composition completely. For the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, he made large-scale symphonic arrangements of Bach and Handel's works, as well as wrote his Empire March and Eight songs. He was appointed Master of the King's Musick on May 1324, just short of these were published. Sir Walter Parratt's death was announced soon after.

Elgar began recording his own works in 1926. Robert Philip, a music writer, had already recorded much of his songs by the time of acoustic recording process for His Master's Voice (HMV), but the introduction of digital microphones in 1925 turned the gramophone from a novelty to a useful tool for reproducing orchestral and choral music. Elgar was the first composer to profit from this technological breakthrough. Fred Gaisberg, a producer of Elgar's albums, arranged a series of sessions to capture the composer's interpretations of his major orchestral works, including the Enigma Variations, Falstaff, the first and second symphonies, and the cello and violin concertos. For the most part, the orchestra was the LSO, but the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra performed Variations. Elgar performed two newly founded orchestras, Boult's BBC Symphony Orchestra, and Sir Thomas Beecham's London Philharmonic Orchestra, later in the series of recordings.

Both HMV and RCA Victor's recordings Elgar's songs were released on 78-rpm discs. The Violin Concerto with the teenage Menuhin as soloist on 78 and later on LP, but most of the other recordings were out of the catalogs for some years. Many conductors were taken aback by their fast tempi when they were reissued by EMI on LP in the 1970s, in comparison to the slower speeds adopted by some conductors in the years since Elgar's death. In the 1990s, the recordings were reissued on CD.

Elgar was filmed by Pathé in November 1931 as part of a news story about a recording session of Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 at the opening of EMI's Abbey Road Studios in London. It is said to be Elgar's only surviving sound film, and he makes a brief remark before conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, asking the players to "play this song as though you've never heard it before." On June 24, 1993, a memorial plaque to Elgar at Abbey Road was unveiled.

The Nursery Suite, Elgar's late piece, was the first example of a studio premiere: it was performed in the Abbey Road studios. Elgar drew on his youthful sketch-books for this project, which was dedicated to the Duke of York's wife and daughters.

Elgar's musical revival came in his last years. In 1932, the BBC held a festival of his art to commemorate his seventy-fifth birthday. He went to Paris in 1933 to conduct the Violin Concerto for Menuhin. He visited Frederick Delius, a French composer, at his house in Grez-sur-Loing. Adrian Boult, Malcolm Sargent, and John Barbirolli, who championed his music when it was out of style, were all keen to hear him. He began working on an opera, The Spanish Lady, and was given a grant by the BBC to conduct a Third Symphony. Their completion was delayed due to his illness. He was worried about the unfinished projects. Reed begged Reed to make sure no one "tinker" with the plans and try to get to the end of the symphony, but "If I can't finish the Third Symphony, someone will finish it – or write a better one." Percy M. Young, a BBC and Elgar's daughter Carice, created a version of The Spanish Lady, which was not released on CD after Elgar's death. In 1997, composer Anthony Payne developed the Third Symphony sketches into a complete score.

During an operation on October 8, 1933, an inoperable colorectal carcinoma was discovered. Arthur Thomson, his consulting doctor, told him he had no interest in an afterlife: "I believe there is nothing but complete oblivion." Elgar died on February 23, 1934 at the age of seventy-six, and his wife was buried next to him at St Wulstan's Roman Catholic Church in Little Malvern.

Influences, antecedents and early works

Elgar dismissed folk music and showed no interest in or admiration for the early English composers, instead referring to William Byrd and his contemporaries as "museum pieces." Purcell was regarded as the best in later English composers by the emperor, and he claimed that he learned a lot of his own technique from studying Hubert Parry's works. Handel, Dvok, and, in some degree, Brahms were among the continental composers who most inspired Elgar. Wagner's influence is evident in Elgar's chromaticism, but Elgar's unique style of orchestration adds to the clarity of nineteenth-century French composers, Berlioz, Massenet, Saint-Saens, and, in particular, Delibes, whose music Elgar performed and enjoyed at Worcester and much admired.

Elgar began writing as a child, and throughout his life, he relied on his early sketchbooks for themes and inspiration. He began making his compositions, even large ones, from scraps of themes that never emerged spontaneously throughout his life. His early adult works included violin and piano pieces, music for the wind quintet in which he and his brother performed between 1878 and 1881, as well as music for the Powick Asylum band. Some of the childhood sketches are included in Grove's Dictionary by Diana McVeagh, but only those pieces are played regularly, except Salut d'Amour and (as arranged decades later into the Wand of Youth Suites). During Elgar's first stay in London in 1889–91, the overture Froissart, was a romantic-bravura work with Mendelsohn and Wagner but also showing more Elgarian characteristics. The Serenade for Strings and Three Bavarian Dances were among orchestral works created in Worcestershire over the next two years. Elgar wrote songs and part songs during this period and later. W. H. Reed expressed reservations about these pieces, but praised The Snow, a collection of five songs for contralto and orchestra which is also in the repertory.

Elgar's most popular early works were for chorus and orchestra for the Three Choirs and other festivals. These were The Black Knight, King Olaf, The Light of Life, The Banner of St George, and Caractacus. He also wrote a Te Deum and Benedictus for the Hereford Festival. McVeagh praises his lavish orchestration and inventive use of leitmotifs, but less so on the content of his chosen texts and the patchiness of his inspiration. McVeagh argues that because these 1890s masterpieces were for many years unknown (and performances are still rare), the Enigma Variations' mastery of his first breakthrough, Enigma Variations, seemed to be a sudden shift from mediocrity to genius, but that orchestral skills had been improving throughout the decade.

Elgar's best-known works were created between 1900 and 1920 within the 20-one years between 1899 and 1920. The bulk of them are orchestrated. "Elgar's genius soared to its highest point in his orchestral works," Reed said, "The orchestral part of the composer's odeographism is the most significant." Elgar's name was also recognized nationally by the Enigma Variations. At this stage of his career, the variation style was appropriate, despite his tendency to write his melodies in short, often rigid terms. The first two Pomp and Circumstance marches (1901), as well as the gentle Dream Children (1902), are short: Cockaigne, his newest orchestral work, is less than fifteen minutes. Despite being listed by Elgar as a concert-overture, Elgar's book The South (1903–1904) was actually a tone poem and the longest piece of strictly orchestral writing Elgar had written. He wrote it after abandoning an attempt to produce a symphony. The writing reveals his continuing improvement in writing sustained themes and orchestral lines, although some commentators, including Kennedy, claim that "Elgar's inspiration burns at a lower price than its highest." Elgar's introduction and Allegro for Strings were completed in 1905. This book is based on a collection of themes, but not on any of Elgar's earlier writings. Kennedy called it a "masterly composition, equalled among English works for strings only by Vaughan Williams' Tallis Fantasia."

Elgar produced three major concert pieces in the next four years, although shorter than those of his European contemporaries, and they are among the few English composers to produce such works. These were his First Symphony, Violin Concerto, and Second Symphony, which all took place between forty-five minutes and an hour. McVeagh explains that the symphonies were "not only in Elgar's output but also in English musical history." Both are long and robust, but without published plans, only hints and quotations to point at some inward drama from which they derive their vitality and eloquence. Both are based on classical form, but they differ from it to the extent that some commentators characterized them as prolix and sluggishly constructed. The invention is certainly rich,; each symphony will require several dozen musical examples to map its progress."

In the view of Kennedy, Elgar's Violin Concerto and Cello Concerto were not only among his finest creations but also among the finest of their kind." They are, however, quite different from each other. The Violin Concerto, which was created in 1909 as Elgar's fame rose and wrote about the instrument closest to his heart, is lyrical throughout and dazzling by turns. The Cello Concerto, which took place a decade after World War I, seems to be "to belong to another time, another world... the simplest of all Elgar's major works, though not necessarily the most opportune." Between the two concertos came Elgar's symphonic study Falstaff, which has split opinion even among Elgar's most ardent supporters. Donald Tovey described it as "one of the most gratifying things in music" with power "identical to Shakespeare's," while Kennedy chastised the work for "too frequent reliance on sequences" and an over-idealized interpretation of the female characters. Reed believed that the main themes show less variation than those of Elgar's earlier works. Falstaff was deemed by Elgar as the best example of his pure orchestral work.

Three major works for voices and orchestra of Elgar's middle period include three large-scale works for soloists, chorus, and orchestra: the Dream of Gerontius (1903), and The Kingdom (1906); and two shorter odes, Coronation Ode (1902) and The Music Makers (1912). The first of the odes, which was a pièce d'occasion, has rarely been revived after its initial success, with the climactic "Land of Hope and Glory" ending. The second book by Elgar is unusual in that it contains several quotations from his earlier work, as Richard Strauss quoted himself in Ein Heldenleben. Both choral performances were highly appreciated, but Gerontius, the first, was and remains the best-loved and most performed. "This is the best of me," Elgar wrote on the manuscript, quoting John Ruskin; for the rest, I ate, and drank, loved, and feared like another; My life was and is not vain; but this I saw and knew; if anything of mine is worth your time," I said. All three of the large-scale works follow the traditional model with sections for soloists, chorus, and mixed ensembles. Elgar's distinct orchestration, as well as his melodic inspiration, elevates them to a higher level than any of their British predecessors.

Elgar's other works from his middle period include incidental music for Grania and Diarmid, George Moore and W. B. Yeats (1901), and The Starlight Express, a play based on a story by Algernon Blackwood (1916). Yeats described Elgar's music as "wonderful in its heroic melancholy." During his peak period, Elgar wrote a number of songs, of which Reed acknowledges: "I cannot say that he enhanced the vocal repertory to the same degree as he did with the orchestra."

Elgar also created no more large-scale works after the Cello Concerto. He made arrangements for Bach, Handel, Chopin's work in a distinctly Elgarian order, and he turned his teenage notebooks to use for the Nursery Suite (1931). His other works from that period haven't been included in the regular repertory. Elgar's creative impulse slowed after his wife's death, according to the majority of the twentieth century. The transformation of Elgar's Third Symphony's sketches into a complete score by Anthony Payne resulted in a revision of this supposition. Elgar finished the symphony in complete score, and those pages, as well as others, reveal Elgar's orchestration has departed sharply from his pre-war career's richest. The Gramophone characterized the new work's opening as something "thrilling... unfortably gaunt." The BBC Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Davis performed in London on February 15, 1998, for the first public performance. Payne produced also a live version of the sketches for a sixth Pomp and Circumstance March, which premiered at the Proms in August 2006. Elgar's sketches for a piano concerto from 1913 were elaborated by composer Robert Walker, who first appeared in August 1997 by pianist David Owen Norris. The realisation has since been extensively redesigned.

Elgar's stature has shifted in the decades since his music rose to prominence in the twentieth century. Richard Strauss praised Elgar as a progressive composer, while the nefarious reviewer in The Observer, who was dissatisfied with the First Symphony's thematic content, called the orchestration "magnificently modern." "The greatest modern composer" in any region, according to Hans Richter, and Richter's colleague Arthur Nikisch rated the First Symphony "a masterpiece of the first order" to be "justly ranked with the greatest symphonic styles – Beethoven and Brahms." In comparison, critic W. J. Turner, a mid-twentieth century scholar, wrote of Elgar's "Salvation Army symphonies," and Herbert von Karajan described the Enigma Variations as a "second-hand Brahms." Elgar's burgeoning success did not last long. After the success of his First Symphony and Violin Concerto, his Second Symphony and Cello Concerto were politely received, but not with the same ferocious enthusiasm as those of earlier years. His music was recognizable in the public eye during the Edwardian period, but he no longer seemed to be a modern or progressive composer after the First World War. Even the First Symphony of the 1920s had just one London appearance in more than three years. Wood and younger conductors, such as Boult, Sargent, and Barbirolli, championed Elgar's music, but his works were not well represented in recording catalogs and concert programs of the middle of the century.

Edward J. Dent, a music scholar, wrote an article for a German music journal in which he outlined four elements of Elgar's style that gave offence to a portion of English opinion (including Dent's scholarly and snobbish section): "too emotional," "not quite free of vulgarity," "pompous," and "too noble in expression); This essay was first published in 1930 and sparked controversy. At least there was a revival of concern in Elgar's music in the later decades of the century. The features that had offended austere taste in the interwar years were seen from a different angle. The records book The Record Guide, published in 1955, discussed the Edwardian roots during Elgar's career: "Undergar's career, 1956."

A less scathing picture of the Edwardian period was emerging by the 1960s. Elgar reflected the last blaze of opulence, dynamism, and full-blooded life before World War II swept so much away. Both the period and Elgar's music were marked by vulgarity, according to Howes' view, but "a composer is entitled to be rated by posterity for his best work." ... Elgar has been instrumental in giving English music a sense of the orchestra by describing what it was like to be alive in the Edwardian period and subsequently returning England to the comity of musical nations.

In 1967, critic and scholar David Cox raised the issue of Elgar's ostensibly Englishness. Elgar disliked folk-songs and never used them in his art, opting for a German idiom that was mainly French, leftned by a lightness derived from French composers such as Berlioz and Gounod. How can Elgar be "the most English of composers," Cox asked. "could use the alien idioms in such a way as to make them an essential form of expression that was neither his nor alone," Cox found in Elgar's own personality. "English is the word that comes through in the music, and it's also a personality." Elgar's transmuting his powers had already been discussed before. "Someone tried to show that Elgar's first symphony was based on the Grail theme in Parsifal," the Times reported in 1930. But the attempt fell flat because everyone else, including those who disliked the song, knew it as 'Elgarian,' though Wagner's Grail theme is more typical. "Englishness" by Elgar's fellow-composers understood it, and Sibelius called him "the personification of the authentic English character of music — a noble personality and a born aristocrat."

There is disagreement among Elgar's followers over which of his creations should be regarded as masterpieces. Enigma Variations are usually included in their rankings. Elgarians have lauded Gerontius's dream, and the Cello Concerto has been lauded. Many people rank the Violin Concerto as highly rated, but some do not. In The Record Guide, Sackville-West dropped it from the list of Elgar masterpieces, and Daniel Gregory Mason wrote a long analysis of the first movement of the concerto for a "kind of sing-songiness... as fatal to a noble rhythm in music as it is in poetry." Falstaff has also divided opinion. It has never been a big hit, and Kennedy and Reed point to its flaws in it. Many contributors support Eric Blom's assertion that Falstaff is the best of all Elgar's works in a Musical Times centennial symposium on Elgar led by Vaughan Williams.

The two symphonies are even more divided on opinion. Mason assigns a poor rating to the Second's "overtonic rhythmic scheme," but Wright praises the First "Elgar's masterpiece." ... It's impossible to imagine how any candid student would deny this symphony's splendor." However, several leading Elgar admirers have voiced reservations about one or both symphonies in the 1957 centennial symposium. "For some reason few people seem to like the two Elgar symphonies equally; each has its champions, and many of them are more interested in the rivalry than others." "There are no sadder pages in symphonic literature than at the start of the First Symphony's Adagio," John Warrack wrote, whereas Michael Kennedy's movement is notable for its lack of anthex and despair, despite its rather positive mood.

Despite the varying critical appraisal of the works over the years, Elgar's major works taken as a whole have recovered strongly from their neglect in the 1950s. Only one of the First Symphony's currently available recordings of the First Symphony, none of the Second, two of the Cello Concerto, two of Falstaff's Enigma Variations, none of which was The Dream of Gerontius, appeared in the Record Guide in 1955. Since then, there have been numerous recordings of all the major works. For example, more than thirty recordings of the First Symphony have been made, as well as more than a dozen of The Dream of Gerontius. Elgar's performances, as in the concert hall, are also highly anticipated. The Elgar Society's website lists performances of Elgar's works by orchestras, soloists, and conductors from around Europe, North America, and Australia.