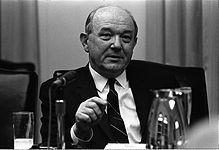

Dean Rusk

Dean Rusk was born in Cherokee County, Georgia, United States on February 9th, 1909 and is the Politician. At the age of 85, Dean Rusk biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 85 years old, Dean Rusk physical status not available right now. We will update Dean Rusk's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909 – December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Rusk is one of the longest serving U.S. Secretaries of State, behind only Cordell Hull. Born in Cherokee County, Georgia, Rusk taught at Mills College after graduating from Davidson College.

During World War II, Rusk served as a staff officer in the China Burma India Theater.

He was hired by the United States Department of State in 1945 and became Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs in 1950.

In 1952, Rusk became president of the Rockefeller Foundation. After winning the 1960 presidential election, Kennedy asked Rusk to serve as secretary of state.

He supported diplomatic efforts during the Cuban Missile Crisis and, though he initially expressed doubts about the escalation of the U.S. role in the Vietnam War, became known as one of its strongest supporters.

Rusk served for the duration of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations before retiring from public office in 1969.

After leaving office, he taught international relations at the University of Georgia School of Law.

Childhood and education

David Dean Rusk was born in a rural Cherokee County, Georgia. The Rusk ancestors had emigrated from Northern Ireland around 1795. His father Robert Hugh Rusk (1868–1944) had attended Davidson College and Louisville Theological Seminary. He left the ministry to become a cotton farmer and school teacher. Rusk's mother Elizabeth Frances Clotfelter was of German and Irish extraction. She had graduated from public school, and was a school teacher. When Rusk was four years old, the family moved to Atlanta where his father worked for the U.S. Post Office. Rusk came to embrace the stern Calvinist work ethic and morality.

Like most white Southerners, his family was Democratic; young Rusk's hero was President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southern president since the Civil War era. The experience of poverty made him sympathetic to black Americans. As a 9 year old, Rusk attended a rally in Atlanta where President Wilson called on the United States to join the League of Nations. Rusk grew up on the mythology and legends of the "Lost Cause" so common to the South, and he came to embrace the militarism of Southern culture as he wrote in a high school essay that "young men should prepare themselves for service in case our country ever got into trouble." At the age of 12, Rusk had joined the ROTC, whose training duties he took very seriously. Rusk had an intense reverence for the military and throughout his later career, he was inclined to accept the advice of generals.

He was educated in Atlanta's public schools, and graduated from Boys High School in 1925, spending two years working for an Atlanta lawyer before working his way through Davidson College, a Presbyterian school in North Carolina. He was active in the national military honor society Scabbard and Blade, becoming a cadet lieutenant colonel commanding the Reserve Officers' Training Corps battalion. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1931. While at Davidson, Rusk applied the Calvinist work ethic to his studies. He won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University. He studied international relations, taking an MA in PPE (Politics, Philosophy and Economics). He immersed himself in English history, politics, and popular culture, making lifelong friends among the British elite. Rusk's rise from poverty made him a passionate believer in the "American Dream", and a recurring theme throughout his life was his oft-expressed patriotism, a place in which he believed that anyone, no matter how modest their circumstances, could rise up to live the "American Dream".

Rusk married Virginia Foisie (October 5, 1915 – February 24, 1996) on June 9, 1937. They had three children: David, Richard, and Peggy Rusk.

Rusk taught at Mills College in Oakland, California, from 1934 to 1949 (except during his military service), and he earned an LL.B. degree at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law in 1940.

Career prior to 1961

He received the Cecil Peace Prize in 1933 while attending St. John's College in Oxford. In an interview with Rusk, his memories of the events of the early 1930s influenced his later views: he told Karnow in an interview:

Rusk spent his time in the Army reserves in the 1930s. In December 1940, he was called to active service as a captain. He served as a staff officer in the China Burma India Theater. Rusk had approved an air drop of arms to the Viet Minh guerrillas in Vietnam commanded by his former ally Ho Chi Minh during the conflict. He was a colonel with the Legion of Merit's Oak Leaf Cluster at the end of the war.

Rusk returned to America to work with the War Department in Washington for a short time. In February 1945, he joined the Department of State and worked in the office of United Nations Affairs. At the 38th parallel north, he suggested that Korea be divided into spheres of US and Soviet influence. According to Max Lowenthal, Rusk succeeded him after Alger Hiss left state in January 1947 (as director of the Office of Special Political Affairs).

Rusk was a promoter of the Marshall Plan and the United Nations Nations. He advised Truman against recognizing Israel fearing that it would jeopardize ties with oil-rich Arab countries like Saudi Arabia, but Truman's legal counsel, Clark Clifford, advised him not to recognize Israel in 1948. When Marshall was asked why he did not resign over Israel's recognition, he replied that the secretary of state did not resign over decisions made by the president, who had the ultimate responsibility of foreign policy. Rusk, who admired Marshall, supported his decision and quoted Truman's words: "The president makes the foreign policy." Under Dean Acheson, who had replaced Marshall as the state secretary of state in 1949, he was made deputy undercoverary of state undercoverary of state.

Rusk was appointed deputy secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs in 1950 at his own initiative, arguing that he knew Asia the best. He was instrumental in the US's decision to participate in the Korean War and in Japan's postwar compensation for victorious nations, as shown in the Rusk documents. Rusk was a skepticism diplomat who had always sought foreign recognition. Rusk favored Asian nationalist movements, arguing that European imperialism had been doomed in Asia, but Acheson, the Atlantic, forbaded European Union support for Asian nationalism. Rusk dutifully stated that it was his duty to help Acheson.

Rusk argued in favor of the French government when it came up that the US should support France in retaining control over Indochina against the Communist Viet Minh rebels, arguing that the Viet Minh were just the weapons of Soviet expansionism in Asia, and refusing to support the French would be appeasement. The French granted nominal autonomy to Vietnam under intense American pressure in February 1950 under Emperor Bao Dai's reign in February 1950, which the US recognized within days. However, it was widely reported that the State of Vietnam was still a French colony as French officials ruled all of the main ministries and the Emperor remarked to the public: "What they call a Bao Dai solution turns out to be just a French one." Rusk testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in June 1950: "This is a civil war that has been captured by the [Soviet] Politburo and, in addition, has been turned into a tool of the Politburo." So, it isn't really a civil war in the normal sense. We must investigate which front we are on in this particular war because Ho Chi Minh is tied to the Politburo, but we can't help Bao Dai and the French in Indochina until we have time to help them establish a going concern."

Truman fired General Douglas MacArthur as the commander of the American forces in Korea in April 1951 over a question over whether to carry the war to China. General Omar Bradley, the Joint Chiefs of Staff's chairman, declared the war against China "the wrong war, in the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy." Rusk delivered a speech at a diner sponsored by the China Institute in Washington in May 1951, where he said that the US should unify Korea under Syngman Rhee and overthrowrow Mao Zedong in China. Rusk's address attracted more attention than he expected, as columnist Walter Lippmann's column "Bradley vs. Rusk" accused Rusk of encouraging a policy of unconditional surrender in the Korean war. Rusk was forced to resign and enter the private sector as the head of the Rockefeller Foundation due to humiliating Acheson.

While Rusk and his family were living in Scarsdale, New York, he served as a Rockefeller Foundation trustee from 1950 to 1961. He succeeded Chester L. Barnard as president of the foundation in 1952.