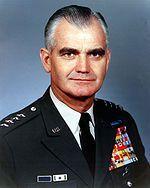

William Westmoreland

William Westmoreland was born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, United States on March 26th, 1914 and is the War Hero. At the age of 91, William Westmoreland biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 91 years old, William Westmoreland physical status not available right now. We will update William Westmoreland's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

William Childs Westmoreland (March 26, 1914 – July 18, 2005) was a United States Army general and the most notable commander of US forces during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1968.

From 1968 to 1972, he served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army. Westmoreland has devised an attrition scheme against the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, aiming to deplete them of manpower and supplies.

He also used artillery and air power, both in tactical combats and in continuous strategic bombardment of North Vietnam.

Many of the Vietnam wars were actually United States victories, with the US Army in command of the field afterward; holding territory gained this way was difficult, however.

Public support for the war has dwindled, particularly after the Battle of Khe Sanh and the Tet Offensive in 1968.

By the time he was recalled as Army Chief of Staff, US military forces in Vietnam had reached their highest level of 535,000 troops.

Westmoreland's program was ultimately ineffective politically.

The growing United States casualties and the draft undermined the United States' support for the war, while non-combatants' casualties weakened South Vietnamese support.

This did also hurt North Vietnam's resolve and the government of South Vietnam, which was largely out of Westmoreland's influence—never succeeded in establishing enough legitimacy to quell defections to the Viet Cong.

Early life

William Childs Westmoreland was born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on March 26, 1914, to Eugenia Talley Childs and James Ripley Westmoreland. His upper middle class family was active in the local banking and textile industries. William became an Eagle Scout in his Boy Scouts of America (BSA) local council Troop 1, and was the recipient of the BSA's Distinguished Eagle Scout Award and Silver Buffalo as a youth. On the nomination of Senator James F. Byrnes, a family friend, after spending a year at The Citadel in 1932, he was accepted to attend the United States Military Academy. "To see the world" was the reason for West Point's arrival. He was a member of a prestigious West Point class that also included Creighton Abrams and Benjamin O. Davis Jr., and the Pershing Sword was awarded, which is "presented to the cadet with the highest level of military skill." Westmoreland has also served as the superintendent of the Protestant Sunday School Teachers.

Personal life

Katherine (Kitsy) Stevens Van Deusen, the future wife of the postman, was born in Fort Sill at the time; she was nine years old at the time and the daughter of the post executive officer, Colonel Edwin R. Van Deusen. Westmoreland was back in North Carolina when she was nineteen and a student at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro. The couple married in May 1947 and had three children: Katherine Stevens, a daughter, James Ripley II; and Margaret Childs, both sons.

Just hours after Westmoreland was sworn in as Army Chief of Staff on July 7, 1968, his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Van Deusen (commander of the 2nd Battalion, 47th Infantry Regiment) was killed while his helicopter was shot down in Vietnam's Mekong Delta region.

Westmoreland died on July 18, 2005 at the age of 91 at the Bishop Gadsden retirement home in Charleston, South Carolina. During his remaining years of his life, he suffered from Alzheimer's disease. He was buried on July 23, 2005 at the West Point Cemetery, the United States Military Academy's West Point Cemetery.

In his honor, the General William C. Westmoreland Bridge in Charleston, South Carolina, has been named in his honor.

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) accepted the award in 1996. General William C. Westmoreland was a recipient of the award. Every year, the award is given to an outstanding SAR veteran volunteer.

William Westmoreland was inducted by the governor of Illinois as a Laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois in 1970 and given the Order of Lincoln (the state's highest award) in the field of Government.

Military career

Westmoreland earned his degree from West Point in 1936 and spent time in Fort Sill with the 18th Field Artillery. After being promoted to first lieutenant and battalion staff officer with the 8th Field Artillery at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, in 1939, he was promoted to first lieutenant.

Westmoreland fought with the 34th Field Artillery Battalion, 9th Infantry Division, in Tunisia, Sicily, France, and Germany; he commanded the 34th Battalion in Tunisia and Sicily during World War II; On October 13, 1944, he was appointed the head of staff of the 9th Infantry Division, earning him the temporary wartime rank of colonel.

Westmoreland completed paratrooper training at the Army's jump school in 1946, just after the war. He commanded the 543th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the 82nd Airborne Division. He served as the chief of staff for the 82nd Airborne Division from 1947 to 1950. He served at Command and General Staff College from August to October 1950, as an instructor at the newly formed Army War College from October 1950 to July 1952.

Westmoreland commanded the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team in Japan and Korea from July 1952 to October 1953. In November 1952, he was appointed to brigadier general at the age of 38, making him one of the youngest US Army generals to serve in the post-World War II period.

Westmoreland was deputy chief of staff, G-1, for manpower control on Army employees until 1955, after returning to the United States in October 1953. Westmoreland began a three-month management course at Harvard Business School in 1954. "Westy was a company executive in uniform," Stanley Karnow said. He served as the US Army's Secretary of the General Staff from 1955 to 1958. He served the 101st Airborne Division from 1958 to 1960. He served as the head of the United States Military Academy from 1960 to 1963. Westmoreland was accepted as an honorary member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati in 1962. He was promoted to lieutenant general in July 1963 and was Commanding General of the XVIII Airborne Corps from 1963 to 1964.

Following World War II, the failed French re-colonization of Vietnam culminated in a decisive French victory at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Former emperor BI ruled Vietnam from April 26 to July 20, 1954. The Geneva Conference (April 26 – July 20, 1954) discussed the possibility of restoring peace in Indochina and briefly divided Vietnam into two zones, a northern zone to be governed by the Vietchinh, and a southern zone to be ruled by the State of Vietnam. The final declaration of a conference, drafted by the British chairman of the conference, required that a general election be held by July 1956 to establish a united Vietnamese republic. Despite being viewed as a consensus view, this paper was not accepted by the delegates of either the State of Vietnam or the United States. In addition, China, the Soviet Union, and other communist nations recognized the North, while the United States and other non-communist states recognized the South as the legitimate government. By the time Westmoreland became the army commander in South Vietnam, the option of a Korean-style settlement split north and south, which had been favored by military and diplomatic analysts, had been ruled out by the US government to win a decisive victory but not to use vastly more money. Regular North Vietnam forces' infiltration into the South could not be dealt with by aggressive measures against the northern state because China's involvement was something the US government was keen to prevent, but President Lyndon B. Johnson had pledged to uphold South Vietnam against communist North Vietnam.

Until defeating the Communists, Army Chief of Staff Harold Keith Johnson came to see U.S. targets as being increasingly incompatible, since defeating the Communists would necessitates a national emergency and effectively mobilizing the US resources. GM was critical of Westmoreland's defused corporate appearance, considering him overattentive to what government officials wanted to hear. Nonetheless, Westmoreland was operating within long-running army policies of subordinationing the military to civilian policymakers. The most significant constraint was being on the defensive as a result of fear of Chinese interference, but at the same time, President Lyndon B. Johnson had made it clear that a greater commitment to protecting Vietnam was present. A substantial portion of the defense discussion was conducted by academics and government consultants who concentrated on nuclear weapons, who were seen as making conventional war obsolete. The role of conventional warfare has also been denigrated by the movement for counter-insurgency thought. Despite the inconclusive conclusion of the Korean War, Americans hoped that their wars would come to an end with the enemy's unconditional surrender.

The Gulf of Tonkin event on August 2, 1964, which culminated in an increase in direct American involvement in the conflict, with nearly 200,000 troops deployed by the year's end. Westmoreland was facing a dual threat thanks to the successful Cong and PAVN's management, grouping, and organization. Regular North Vietnamese army units advancing across the rural border were reportedly concentrating on an assault, and Westmoreland viewed this as the threat that must be addressed right away. By the Viet Cong, there was also deep guerrilla subversion throughout the heavily populated coastal areas. Westmoreland continued to emphasize body count and cited the Battle of Ia Drang as proof that communists were losing, despite Robert McNamara's enthusiasm for statistics. However, the government wanted to win at low cost, and policymakers received McNamara's analysis hinting at significant American casualties in the future, prompting a reassessment of what could be achieved. In addition, the Battle of Ia Drang was the first battle in which US troops carried a large enemy army unit to combat. After speaking with junior officers, General Westmoreland became skeptical about localized targeted search and destroy sweeps of short durations because Communist forces controlled whether there were military involvements, giving the option to simply avoid conflict with US forces if the circumstances permitted it. Because it was politically ineffective, the alternative of sustained pacification operations, which would necessitated the use of a lot of US manpower, was never available to Westmoreland.

At least, he was curious about the progress made during his time in Vietnam, but loyal journalist James Reston said Westmoreland's portrayal of the conflict as attrition warfare painted his generalization in a misleading manner. According to Westmoreland's analysts, his replacement, GM Creighton Abrams, deliberately switched the focus away from what Westmoreland calls attrition. Revisionists point to Abrams' first major operation as a tactical success that disrupted North Vietnamese buildup, but it culminated in the Battle of Hamburger Hill, which effectively ended Abrams' ability to continue with such operations.