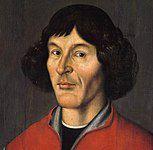

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Toru, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland on February 19th, 1473 and is the Astronomer. At the age of 70, Nicolaus Copernicus biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 70 years old, Nicolaus Copernicus physical status not available right now. We will update Nicolaus Copernicus's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Nicolaus Copernicus (Polish: Mikolaj Kopernik; German: Niklas Koppernigk) was a Renaissance-era polymath who built a model of the Sun rather than Earth at the center of the universe, perhaps without Aristarchy of Samos, who had conceived it in 1543) and contributed to the Scientific Revolution in the region.

He earned a doctorate in canon law and served as a mathematician, astronomer, poet, classics scholar, translator, governor, and economist.

He derived the quantity theory of money, a key concept in monetary economics, in 1517, and in 1519, he introduced an economic principle that would later be referred to as Gresham's law.

Life

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Toru (Thorn), in the province of Royal Prussia's Province, on the Crown of Poland.

His father was a merchant from Kraków, and his mother was the daughter of a wealthy Toru merchant. Nicolaus was the youngest of four children. Andreas (Andrew) is a student at Frombork (Frauenburg), and he became an Augustinian canon. Barbara, a boy named after her mother, became a Benedictine nun and, in her remaining years, she was a prioritizing a convent in Chemno (Kulm), and died in 1517. Katharina married Barthel Gertner, the businessman and Toru's city councilor, and left five children with whom Copernicus looked after until the end of his life. Copernicus never married and is not believed to have had children, but two bishops of Warmia urged him to break off all contact with his "mistress" from 1531 to 1539.

The father of Copernicus can be traced back to a village in Silesia between Nysa (Neiße) and Prudnik (Neustadt). The village's name has been variously spelled Kopernik, Copernik, Copernic, Kopernic, Coprirnik, and Kopernik, while today Kopernik is the village's official language. Members of the family began moving to many other Silesian cities, Kraków (1367) and Toru (1400). Mikoaj the Elder, the father, is a Jew, who was evidently the son of Jan.

Nicolaus was named after his father, who appears in newspapers for the first time as a well-to-do copper dealer who sold copper, but mostly in Danzig (Gda). Around 1458, he moved from Kraków to Toru. Toru, which is located on the Vistula River, was embroiled in the Thirteen Years' War, during which the Kingdom of Poland and the Prussian Confederation, a union of Prussian cities, gentry, and clergy, fought the Teutonic Order over the area's control. Hanseatic cities, including Danzig and Toru, Nicolaus Copernicus' hometown, decided to support the Polish King, Casimir IV Jagiellon, who had promised to protect the cities' ancient vast autonomy, which was challenging the Teutonic Order. Nicolaus' father was active in the day's politics and argued for Poland and the cities against the Teutonic Order. In 1454, he mediated talks between Poland's Cardinal Zbigniew Olenicki and the Prussian cities for repayment of war loans. The Teutonic Order officially resigned all claims to its western province, which was largely held by the Crown of Poland until the First (1772) and Second (1793) Partitions of Poland in the Second Peace of Thorn (1466).

Between 1461 and 1464, Copernicus' father married Barbara Watzenrode, the astronomer's mother. He died about 1483.

Barbara Watzenrode, the niece of a wealthy Toru patrician and city councillor, Lucas Watzenrode (deceased 1462), and Katarzyna (widow of Jan Peckau) were among Nicolaus's relatives, according to other sources as Katarzyna Rüdiger gente Modlibóg (deceased 1476). The Modlibógs were a prominent Polish family who had not been active in Poland's history since 1271. The Watzenrode family, as well as the Kopernik family, had come from Silesia near Schweidnitz, and after 1360, had settled in Toru. They soon became one of the most wealthy and influential patrician families. Copernicus was linked to wealthy families of Toru (Thorn), Gda (Elbing), and Elblg (Elbing), as well as well-known Polish noble families of Prussia: the Czapskis, Dziaskis, Konopackis, and Kocieleckis, according to the Watzenrodes. Lucas Watzenrode the Younger (1447-1512), who would become the patron of Warmia and Copernicus; Barbara, the astronomer's mother (deceased after 1495); and Christina (deceased before 1502), who married Tiedeman von Allen, the Toru merchant and mayor, in 1459.

Lucas Watzenrode the Elder, a wealthy merchant and in 1439-62 president of the judiciary bench, was a vocal critic of the Teutonic Knights. He delegated Toru's delegate to the Grudzi (Graudenz) conference in 1453, plotting the revolt against them. He actively supported the Prussian cities' war effort with substantial financial assistance (only part of which he later reclaimed), political involvement in Toru and Danzig, and personal combat in battles at asin (Lessen) and Malbork (Marienburg). He died in 1462.

Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, the astronomer's maternal uncle and patron, was educated at the University of Kraków (now Jagiellonian University) and at the universities of Cologne and Bologna. He was a vociferous critic of the Teutonic Order, and its Grand Master once referred to him as "the devil incarnate." In 1489, Watzenrode was elected Bishop of Warmia (Ermeland, Ermland) against King Casimir IV's choice, who had hoped to install his own son in the position. As a result, Watzenrode quarreled with the king until Casimir IV's death three years later. Watzenrode was able to develop close friendships with three Polish monarchs, including John I Albert, Alexander Jagiellon, and Sigismund I the Old. He was a mentor and a leading strategist to each emperor, and his presence only enhanced the ties between Warmia and Poland. Watzenrode used to be Warmia's most influential man, and his wealth, links, and celebrity enabled him to obtain Copernicus's education and work as a canon at Frombork Cathedral.

Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, a young Nicolaus' maternal uncle (1447–1512) took the child under his wing and saw to his education and work following his father's death. Watzenrode maintained links with leading academic figures in Poland and was a mentor of influential Italian-born humanist and Kraków courtier Filippo Buonaccorsi. There are no surviving primary sources on Copernicus's childhood and education in the early years. Young Copernicus was first sent by Watzenrode to St. John's School, where he had been born a master. Copernicus biographers assume he was the first one to attack Toru. The boy later attended the Cathedral School at Woc Awek, up the Vistula River from Toru, which prepared students for admission to the University of Kraków, Poland's capital, according to Armitage.

"Nicolaus Nicolai de Thuronia," a boy from 1491-92, matriculated at the University of Kraków (now Jagiellonian University). Copernicus began his studies in the Department of Arts (probably before the fall or the fall of 1495) in Kraków's astronomical-mathematical school, where he gathered the foundations for his subsequent mathematical accomplishments. Copernicus was a pupil of Albert Brudzewski's Theoric Nov. 746, but he taught astronomy privately outside the university, according to a later but reliable tradition (Jan Broek); Copernicus was an astronomer who wrote about Bernard of Biskupie and Wojciech Krypa's work in Wrocojewy (Breslau) and perhaps other astronomical lectures by Jan of Groo o,

Copernicus's Kraków studies gave him a deep insight into the astronomy taught at the university (arithmetic, geometry, numerical simulation, simulation, and computational astronomy), as well as a good understanding of Aristotle's philosophical and natural-science writings, as well as a growing interest in studying and making him familiar with humanistic history. Copernicus enriched his knowledge by discovering books he borrowed from the university lecture halls during his Kraków years (Euclid, Haly Abenragel, the Alfonsine Tables, Johannes Regiomontanus' Tabulae directionum), which may also refer to his oldest scientific papers, which are now preserved partially at Uppsala University. Copernicus began amassing a large library on astronomy in Kraków; it would later be sold as war booty by the Swedes during the Deluge in the 1650s and is now at the Uppsala University Library.

Copernicus' four years in Kraków contributed to the growth of his critical faculties and led to his investigation of logical contradictions in the two "official" systems of astronomy—Aristotle's model of homocentric spheres and Ptolemy's device of eccentrics and epicycles, the first step toward Copernicus's own philosophy of the universe's system.

Copernicus left Kraków after his uncle, Watzenrode, was appointed to Prince-Bishop of Warmia in 1489 but sadly, until November 1495) and his nephew was released in the Warmia canonry, without having obtained a degree, according to Jan Czanow, who died in the 1380s. For unclear reasons—perhaps due to protests from a portion of the chapter's appeal to Rome—Copernicus's induction was postponed, encouraging Watzenrode to enroll canon law in Italy, perhaps with the intention of improving their ecclesiastic careers and thereby increasing his own authority in the Warmia chapter.

Copernicus succeeded to the Warmia canonry, which had been promised to him two years ago, on October 20, 1497. He would assemble a sinecure at the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross and St. Bartholomew in Wrocaw, which was at the time in Bohemia, according to a paper dating back to 10 January 1503 in Padua. Despite being granted a papal indult on 29 November 1508 to receive additional benefices, Copernicus's ecclesiastic career did not succeed in more prebends and higher stations (prelacies) at the chapter, but it did not win the Wroc in 1538. It's also unknown if he was ever ordained a priest. Edward Rosen denies that he was not. Copernicus did receive minor orders, which was sufficient for the initiation of a chapter canon. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, his ordination was likely, as he was one of four candidates for the episcopal seat of Warmia in 1537, a position that necessitated ordination.

Copernicus arrived in Bologna in mid-1496, possibly in October, as a result of young Poles from Silesia, Prussia, and Pomerania, as well as students of other nationalities, leaving Warmia in mid-1496, possibly in October.

Copernicus appears to have devoted himself less to researching the humanities during his three-year stay in Bologna, between fall 1496 and spring 1501, than to studying astronomy (especially by Filippo Beromando, Giovanni Garzoni, and Alessandro Achillini), rather than to studying astronomy (see below). Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara, the renowned astronomer, became his disciple and assistant. Copernicus was inspired by George von Peuerbach and Johannes Regiomontanus' "Epitome of the Almagest" (Epitome in Almagestum Ptolemei) (Venice, 1496). By carrying out a memorable analysis of the occultation of Aldebaran, the brightest star in the Taurus constellation by the moon's calculations, he confirmed the company's assertions regarding particular peculiarities in Ptolemy's lunar orbit from the moon's orbit by the moon's orbit by the moon. Copernicus the humanist sought confirmation for his growing doubts by close reading of Greek and Latin writers (Pythagoras, Cleomedes, Cicero, Pliny the Elder, Plutarch, Heraclides, Plato), a group of ancient astronomical, cosmological, and calendar texts, particularly in Padua, garnering, especially while visiting Padua, is a popular resource for ancient astronomical, cosmological,

Copernicus spent the jubilee year 1500 in Rome, where he and his brother Andrew arrived in the spring but had no intention of undertaking an apprenticeship at the Papal Curia. Nonetheless, here, he continued his astronomical work at Bologna, including a lunar eclipse on the night of 5–6 November 1500. According to a later account by Rheticus, Copernicus, and, possibly privately, rather than at the Roman Sapienza, a "Professor Mathematum" (professor of astronomy) delivered, "to numerous... students and..." leading experts of the science," according to a critique of contemporary astronomy's mathematical methods.

Doubtless on his return journey, he arrived in Bologna in mid-1501 Copernicus, returning to Warmia. After receiving a two-year leave in order to study medicine [Bishop Lucas Watzenrode] and the chapter's gentlemen, in late summer or fall, he returned to Italy, perhaps with his brother Andrew and Canon Bernhard Sculteti. He stayed at Padua from fall 1501 to summer 1503.

Copernicus read medical books that he acquired at this time, by Valescus de Taranta, Jan Mesue, Hugo Senensis, Jan Ketham, Arnold de Villa Nova, and Michele Savonarola, which would form the embryo of his later medical library, and possibly under the direction of respected Padua professors—Bartolomeo da Montagnana, Girolamo Fracastoro, Gabriele Zerbi, Alessa

Astrology was one of Copernicus' requirements, since it was considered a vital component of a medical education. Nevertheless, unlike many other leading Renaissance astronomers, he appears never to have practiced or expressed an interest in astrology.

Copernicus did not restrict himself to his formal studies as he arrived in Bologna. It was likely that the Padua years were the beginning of his Hellenistic aspirations. With the help of Theodorus Gaza's grammar (1495) and Johannes Baptista Chrestonius' dictionary (1499), he began his antiquity studies, extending his antiquity study to Bessarion, Lorenzo Valla, and others. There are also signs that it was during his Padua stay that the idea of baseding a new model of the world on the Earth's orbiting seems to have surfaced. As the time came for Copernicus' return home, he travelled to Ferrara in spring 1503, where he was granted the Doctor of Canon Law degree (Nicolaus Copernich de Prusia, Jure Canonico et doctoratus). There was no doubt that it was soon after (at the most, in fall 1503) that he left Italy for good to return to Warmia.

Copernicus made three observations of Mercury, with errors of 3, 15, and 1 minutes. He made one of Venus's biggest mistakes, but in the wrong time of 24 minutes, he made it in 24 minutes. Four people were made of Mars, with errors of 2, 20, 77, and 137 minutes. Four observations of Jupiter were made, with errors of 32, 51, 11, and 25 minutes. He made four Saturn variations, with errors of 31, 20, 23, and 4 minutes.

By the moon's occultation of Aldebaran by Novara, Copernicus noted an occultation of Aldebaran by the moon on March 9, 1497. On March 4, 1500, Copernicus observed a conjunction between Saturn and the moon. On November 6, 1500, he witnessed an eclipse of the moon.

Following all his studies in Italy, the 30-year-old Copernicus returned to Warmia, where he will live out the remaining 40 years of his life. Graedz, Kraków (Marienburg), Königsberg (Królewiec), King.

The Prince-Bishopric of Warmia enjoyed a great degree of autonomy, with its own diet (parliament) and monetary unit (the same as in other parts of Royal Prussia) and treasury.

Copernicus was his uncle's secretary and surgeon from 1503 to 1510 (or perhaps until his uncle's death on March 29th, 1512) and spent in Lidzbark (Heilsberg), where he began work on his heliocentric theory. He was instrumental in virtually all of his uncle's political, ecclesiastic, and administrative positions in his official capacity. Copernicus was accompanied by Watzenrode to sessions of the Royal Prussian diet held in Malbork and Elbl'g, and, according to Dobrzycki and Hajdukiewicz, "participated" in all of the most important events in the turbulent diplomatic game played by a passionate politician and statesman in the defense of Prussia and Warmia's particular interests, from hostility to the Polish Crown's [Te

Copernicus spent his travels from Kraków, 1504 to Toru and Gda, to a session of the Royal Prussian Council in the presence of Poland's King Alexander Jagiellon; to Prussia's Prussian diet (1506), Elblg (1507), and Sztum (1512), and a commemoration of Poland's King Sigismund I the Old. According to Watzenrode's itinerary, Copernicus may have attended the Kraków sejm in spring 1509.

Copernicus' translation, from Greek to Latin of 85 short poems by 7th-century Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta, was reportedly published in Kraków on the latter occasion. They are of three kinds: "moral" providing tips on how people should live; "pastoral" giving little pictures of shepherd life; and "amorous" consisting of love poems. They are supposed to follow one another in a regular rotation of subjects. Copernicus had turned the Greek verses into Latin prose, and he now published his version as Theophilacti Simolite stolae morales, rurales et amatoriae latina, which he referred to in honor for all of the benefits he received from him. Copernicus proclaimed himself on the side of the humanists in this conflict over the question of whether Greek literature should be revived. Copernicus' first poetic work was a Greek epigram composed probably during a visit to Kraków for Johannes Dantiscus' epithalamium for Barbara Zapolya's 1512 wedding to King Zygmunt I the Old.

Copernicus outlines a basic outline of his heliocentric theory that was only accessible from later transcripts (perhaps given to it by a copyist), Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuo coelestimus motuo coelestium a se constitutivis commentariolus, which is commonly referred to as the Commentariolus. It was a succinct theoretical description of the world's heliocentric device, without mathematical hardware, and differed in some critical aspects of geometric design from De revolutionibus; however, it was already based on the same assumptions regarding Earth's triple axes. Copernicus deliberately saw the Commentariolus as merely a first draft for his forthcoming book, not intended for print distribution. He made only a few manuscript copies available to his closest acquaintances, including several Kraków astronomers with whom he collaborated in 1515-30 in discovering eclipses. Tycho Brahe will include a fragment from the Commentariol treatise, Astronomiae progymnasmata, which was published in Prague in 1602, based on a manuscript he obtained from Bohemian physician and astronomer Tadeáe Hájek, a Rheticus friend. For the first time since 1878, the Commentariolian will be printed in full.

Copernicus from Frombork, a town on the Baltic Sea coast in 1510 or 1512, migrated to Vistula Lagoon. He was in attendance of the Fabian of Lossainen as the Prince-Bishop of Warmia in April 1512. The chapter gave Copernicus a "external curia" only in early June 1512, a house outside the cathedral's defensive walls. He bought the northwestern tower within the walls of the Frombork stronghold in 1514. Despite the destruction of the chapter's buildings by a raid against Frauenburg that was apparently destroyed by the Teutonic Order in January 1520, during which Copernicus's astronomical equipment were likely destroyed, he would maintain both these residences until the end of his life. Copernicus made astronomical observations in 1513–16, likely from his exterior curia, and in 1522–43, from an unidentified "small tower" (turricula), using primitive technologies modeled on ancient ones: the quadrant, triquetrum, armillary sphere. Over half of his more than 60 registered astronomical observations were made at Frombork Copernicus.

Copernicus discovered himself at the Warmia chapter's economic and administrative center, one of Warmia's two key political centers, having settled permanently in Frombork, where he will live to the end of his life. He was consciously a citizen of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic in the tense, politically complicated situation of Warmia, which were threatened externally by the Teutonic Order's aggressions (the zebratonic Wars of 1519-21; Albert's attempts to annex Warmia); and, in response to the Order's efforts to compel the Polish Crown's commitments; and, proposals to unify the Polish crown's financial system; He participated in the signing of the Second Treaty of Piotrków Trybunalski (7 December 1512), governing the appointment of the Bishop of Warmia, despite opposition from part of the chapter, indicating faithful cooperation with the Polish Crown in the aftermath of uncle Bishop Watzenrode's death.

Copernicus assumed responsibility for the chapter's economic affairs in the same year (before 8 November 1512), having previously served the office as magister pistoriae.

Copernicus, who lived in 1512-15, did not stand still from intense observational work, according to his administrative and economic roles. The findings of his observations of Mars and Saturn in this period, as well as a series of four observations of the Sun made in 1515, led to the discovery of Earth's eccentricity and of the solar apogee's course in relation to the fixed stars, which led to his first revisions of certain assumptions of his system in 1515 to 1915. Any of the observations he made in this period may have been in connection with a proposed extension of the Julian calendar that was initiated in the first half of 1513 by Bishop Fossombrone, Paul of Middelburg. In a treatise by Copernicus' dedication to the D' revolutionibus orbium coelestium, and in a treatise by Paul of Middelburg, Secundum compendium correctionis Calendarii (1516), Copernicus's learned men were among the scheduled men who had submitted the Council's calendar of emendation's emendation, their contacts in this period were later remembered.

Copernicus lived at Olsztyn (Allenstein) Castle as the country's economic administrator, including Olsztyn (Allenstein) and Pienino (Mehlsack). He wrote a book, Locationes mansorum desertorum (Locations of Deserted Fiefs), in the hopes of populating those fiefs with ardent farmers and thus bolstering the economy of Warmia. Copernicus ordered the defense of Olsztyn and Warmia by Royal Polish forces when Olsztyn was besieged by the Teutonic Knights during the Polish-Teutonic War. In the ensuing peace talks, he also represented Poland.

Copernicus has advised the Royal Prussian sejmik on financial reform, particularly in the 1520s, when it was a big issue in regional Prussian politics. "Monetae cudendae ratio" was a research published in 1526. He formulated an early iteration of the belief that "poor" (debased) coinage pulls "good" (un-debased) coinage out of circulation long before Thomas Gresham's book was published. A quantity theory of money was also introduced in 1517, which is the main economic model to this day. Both Prussia and Poland's leaders were highly interested in Copernicus's proposals on monetary reform, which was widely distributed by economists.

Johann Widmanstetter, Pope Clement VII's secretary, explained Copernicus' heliocentric system to the Pope and two cardinals in 1533. The Pope was so delighted that he gave Widmanstetter a thoughtful gift. Bernard Wapowski wrote a letter to a man in Vienna urging him to release an enclosed almanac, which he said had been written by Copernicus. This is the first mention of a Copernicus almanac in historical records. The "almanac" was most likely Copernicus' tables of planetary positions. In his letter, Wapowski addresses Copernicus' theory of the earth's motions. Wapowski's request was not fulfilled because he died a few weeks later.

Copernicus was involved in the assassination of Prince-Bishop Warmia Ferber (1 July 1537). Copernicus was one of four candidates for the post, written at Tiedemann Giese's initiative, but Dantiscus' candidacy was pro forma, since Dantiscus had been named coadjutor bishop to Ferber and that Dantiscus had the support of Poland's King Sigismund I. Copernicus maintained friendly links with the new Prince-Bishop, assisting him surgically in spring 1538 and accompanying him on a tour of Chapter ownerships throughout the summer. However, their friendship was strained by rumors about Copernicus' housekeeper Anna Schilling, whom Dantiscus banished from Frombork in spring 1539.

Copernicus the physician's younger days had abused his uncle, brother, and other chapter members. He was called upon to attend the elderly bishops who in turn occupied the see of Warmia (Mauritius Ferber and Johannes Dantiscus) in Warmia—Mauritius Ferber and Johannes Dantiscus—and, in 1539, his old friend Tiedemann Giese, Bishop of Chemno (Kulm). He often obtained consultations from other doctors, including the physician to Duke Albert and, in particular, the Polish Royal Physician.

Duke Albert, the fourth Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, and Duchy of Prussia's Duchy of Prussia's former emperor, Sigismund I, summoned Copernicus to Königsberg in the spring of 1541, after the Duke of Poland, George von Kunheim, fell seriously ill and for whom the Prussian doctors were unable to do anything. Copernicus accepted the coinage reform; he had met von Kunheim during talks over its reform of the currency. Copernicus had come to the conclusion that Albert himself was not such a bad person; the two had a variety of intellectual interests in common. Despite his Lutheran faith, Copernicus was able to leave Copernicus as it wanted to keep good relations with the Duke. The patient recovered in about a month, and Copernicus returned to Frombork. He continued to get reports on von Kunheim's health and to give him medical assistance by letter for a time.

Copernicus' close friends were converted Protestant, but Copernicus never showed a inclination to go in that direction. Protestants were among the first attacks on him. Wilhelm Gnapheus, a Dutch immigrant who lived in Elblg, wrote a play in Latin called Morosophus (The Foolish Sage) and staged it at the Latin school where he had attended. Copernicus was portrayed as the eponymous Morosophus, a haught, cold, aloof man who dabbled in astrology, and was rumored to have written a large piece moldering in a chest in the play.

Protestants in Elsewhere were among the first to react to Copernicus's news.Melanchthon wrote:

Nonetheless, astronomer Erasmus Reinhold published the Prussian Tables, a collection of astronomical tables based on Copernicus's work in 1551, eight years after Copernicus's death. It was quickly adopted by astronomers and astrologers in place of its predecessors.

Copernicus' "Commentariolus" ("Little Commentary"), a manuscript that outlines his theories of the heliocentric hypothesis, was available to friends some time before 1514. It had seven basic assumptions (detailed below). He collected statistics for a more comprehensive project later.

Copernicus had basically completed his studies on D's orbium coelestium's manuscript by 1532, but despite being encouraged by his closest friends to not reveal his views publicly, not wishing—as he promised—to risk the scorn "to which he would expose himself on account of the novelty and incomprehensibility of his theses."

Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter delivered a series of lectures in Rome debating Copernicus's theology in 1533. Many Catholic cardinals attended the lectures and were intrigued in the theory, including Pope Clement VII. Cardinal Nikolaus von Schönberg, Archbishop of Capua, wrote to Copernicus of Rome on November 1st.

Copernicus' work was approaching its definitive form by then, and rumors about his methodology had captivated educated people from around Europe. Copernicus delayed the publication of his book, perhaps out of fear of criticism, which was clearly expressed in the subsequent dedication of his masterpiece to Pope Paul III. Scholars disagree over whether Copernicus's worry was limited to future astronomical and philosophical reservations, or if he was worried about religious objections.

When Georg Joachim Rheticus, a Wittenberg mathematician, arrived in Frombork in 1539, he was still working on De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (even if he wasn't positive he wanted to publish it). Philipp Melanchthon, a close Martin Luther scholar, had invited Rheticus to visit several astronomers and talk with them. Rheticus was Copernicus's pupil, spending two years with him and a book entitled Narratio prima (First Account), outlining Copernicus's argument. Copernicus' treatise on trigonometry appeared in 1542 (later included in Book I of De revolutionibus, chapters 13 and 14). Copernicus has decided to give De revolutionibus to his close friend, Tiedemann Giese, bishop of Chemno (Kulm), who was under strong pressure from Rheticus and seeing the enthusiastic first general reception of his work, but not to Rheticus, Germany. Although Rheticus supervised the printing, he had to leave Nuremberg before it was finished, and Andreas Osiander, a Lutheran theologian, handed over the remainder of the printing to a Lutheran theologian.

Osiander also published an unauthorised and unsigned preface, protecting Copernicus's efforts against those who might be offended by the organization's novel hypotheses. "Several hypotheses are often proposed for one and the same motion [and, therefore], the astronomer would choose as his first choice, which is the easiest to comprehend," he said. "These hypotheses need not be true or even probable," Osiander says. If they have a calculus that is consistent with the findings, that alone is sufficient."

Copernicus was captured with apprehension and paralysis near the end of 1542, and he died on May 24th, 1543. Legend has it that he was given the final printed pages of his D. revolutionibus orbium coelestium on the day he died, allowing him to say their goodbyes. He is said to have awakened from a stroke-induced coma, read his book, and then died peacefully.

Copernicus was buried in Frombork Cathedral, where a 1580 epitaph was restored in 1735; it was replaced in 1735. Archaeologists have been looking in vain for Copernicus' remains for over two centuries. Efforts to locate them in 1802, 1909, 1939, and 1939 had come to a halt. Jerzy Gssowski, the head of an archaeology and anthropology institute in Putusk, initiated a new investigation in 2004, guided by historian Jerzy Sikorski's findings. They discovered what they suspected to be Copernicus' remains in August 2005 after scanning underneath the cathedral floor.

The find was only revealed after more study, on November 3, 2008. "Almost 100% positive it is Copernicus," Gssowski said. Capt. Capt. forensic expert Capt. On a Copernicus self-portrait, Dariusz Zajdel of the Polish Police Central Forensic Laboratory reconstructed a face that closely resembled the Copernicus's — including a fractured nose and a scar above the left eye. The skull was also determined to belong to a man who had died around age 70—Copernicus's age at the time of his death.

The grave was in poor shape, and not all the bones of the skeleton were discovered; among other things, the lower jaw was missing; The DNA from the bones found in the grave match hair samples obtained from a book owned by Copernicus and housed at the University of Uppsala, Sweden.

Copernicus' second funeral was held in a Mass led by Józef Kowalczyk, the former papal nuncio to Poland and recently named Primate of Poland, on May 22nd. Copernicus' remains were reburied in Frombork Cathedral, where a portion of his skull and other bones were discovered. A black granite tombstone has identifies him as the earliest of the heliocentric belief as well as a church canon. The tombstone depicts Copernicus' Solar System's model, with a golden Sun encircled by six of the planets.