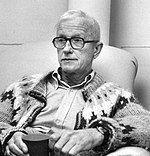

Max Delbruck

Max Delbruck was born in Berlin on September 4th, 1906 and is the Physicist. At the age of 74, Max Delbruck biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 74 years old, Max Delbruck physical status not available right now. We will update Max Delbruck's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück (September 4, 1906 – March 9, 1981), a German-American biophysicist who pioneered the molecular biology research program in the late 1930s, was a pioneer of the field of molecular biology research.

He ignited physical scientists' fascination with biology, particularly in relation to basic research to physically explain genes, which was still unclear at the time.

The Phage Group, founded in 1945 and headed by Delbrück, Salvador Luria, and Alfred Hershey, all made significant contributions to the investigation of genetics.

"For their studies into the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses," the three researchers received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969.

He was the first physicist to predict what is now known as Delbrück scattering.

Early and personal life

Delbrück was born in Berlin, Germany Empire. His mother, Justus von Liebig, a pioneer in the field of chemistry, was his grandmother, and his father, Hans Delbrück, was a history professor at the University of Berlin. Delbrück left Nazi Germany for America in 1937, first California, then Tennessee—becoming a US citizen in 1945. In 1941, he married Mary Bruce. They had four children.

Justus, a lawyer, as well as his sister Emmi Bonhoeffer, were involved in resistance to Nazism, as did his brothers-in-law Klaus Bonhoeffer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The People's Court found guilty of aiding in the assassination of Hitler, Dietrich, and Klaus by the RSHA in 1945. Justus died in Soviet detention the same year.

Education

At the University of Göttingen, Delbrück studied astrophysics, which was transforming to theoretical physics. He travelled through England, Denmark, and Switzerland after completing his Ph.D. there in 1930. He met Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr, who were interested in biology.

Later life and legacy

Physical scientists' interest in biology was sparked by Delbrück's work. In his 1954 book What Is Life?, physicist Erwin Schrödinger's contribution to mutation discovery in a "aperiodic crystal" storage codescript that inspired crystallographer Rosalind Franklin and biologists James D. Watson's 1953 identification of DNA as a double helix. He graduated from Caltech in 1977, remaining a Professor of Biology etus. In the 1960s, he became interested in the behavioral sciences and invested some unsuccessful attempts on mold behavior.

Max Delbrück died on Monday, March 9, 1981, at Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena, California, at the age of 74. Families and friends gathered at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on August 26 to 26, 2006, the year Delbrück would have turned 100. Although Delbrück held some anti-reductionist views, he speculated that a paradox, perhaps related to waveparticle duality of physics, would be revealed about life. His opinion, on the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA, was later refuted.

Career and research

Delbrück returned to Berlin in 1932 as an assistant to Lise Meitner, who was collaborating with Otto Hahn on the irradiation of uranium with neutrons. Delbrück published a few papers, one of which was published in 1933 on gamma rays' scattering by a Coulomb field's polarization of a vacuum. Though strictly tenable, his conclusion was misplaced, though Hans Bethe confirmed the event 20 years later and described it as "Delbrück scattering."

Delbrück published a major work, Über die Natur der Genmutation undistruktur, in 1935. Nikolay Timofeev-Ressovsky and Karl Zimmer collaborated. It was deemed a significant advancement in understanding gene mutation and gene structure. The research was a determining factor in the molecular genetics evolution. It was also a launching point for Erwin Schrödinger's thought, a series of lectures in 1943, and the eventual publication of the book What Is Life? The Living Cell's Physical Aspect.

In 1937, he received a fellowship from Rockefeller Foundation—which was establishing the molecular biology research program—to-test genetics of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, in the biology department of California Institute of Technology, where Delbrück could combine interests in biochemistry and genetics, where Delbrück could combine interests in biochemistry and genetics. Delbrück, a Caltech undergraduate, studied bacteria and their viruses (bacteriophages or phages). Emory L. Ellis coauthored "The growth of bacteriophage," a study that shows that the viruses reproduce in a single step rather than cellular organisms.

Despite the fact that Delbrück's Rockefeller Foundation fellowship ended in 1939, the Foundation matched him up with Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he taught physics from 1940 to 1947 but also had his laboratory in the biology department. Delbrück was visiting Vanderbilt in 1941 and met Salvador Luria of Indiana University. Delbrück and Luria published a study in 1942 on bacterial resistance to virus infection caused by random mutation. In 1943, Alfred Hershey of Washington University began visiting. Darwin's theory of natural selection based on random mutations was also applicable to bacteria and more complex organisms, as shown by the Luria–Delbrück experiment. Both scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contribution to this research in 1969. To put this work into a historical context, Lamarck's 1801 theory of Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics, which stated that if an organism changes during life in order to adapt to its environment (for example, it extends its neck to reach for tall trees), the same changes are passed on to its offspring. Evolution follows a predetermined schedule, according to him. Darwin's theory of evolution was challenged in his 1859 book On the Origins of Species, which had compelling evidence contradicting Lamarck. Darwin said that evolution is not controlled, but that all organisms have inherent variations, and that those that promote increased fitness are inherited by the environment and passed on to the offspring. Darwin talked about pre-existing evolution in Lamarck and Darwin, but Darwin explained that the cause of these changes was not understood and had to await the development of genetics by Gregor Mendel's experiments on pea plants, which were published in 1866. When Thomas Hunt Morgan discovered that a mutated white-eyed fruit fly among red-eyed flies was able to produce true white-eyed offspring, Darwin's theory was backed up by evidence. Darwin's theories, on the other hand, were backed up by the Luria-Delbruck experiment, which showed that mutations transferring T1-bacteriophage (virus) existed in the population long before T1 infection and that T1 bacteria were not induced by adding T1 bacteriophage (virus). In other words, mutations happen randomly, whether or not they are useful, while selection (for T1 resistance against T1 in this case) sets the direction in evolution by retaining those mutations that are beneficial, while discarding those that are detrimental (T1 sensitivity). This experiment put Lamarckian inheritance into question and set the tone for major advances in genetics and molecular biology, sparking a tsunami of research that eventually led to the discovery of DNA as the hereditary material and unlocking the genetic code. Of course, by then Avery and McCloud (and even earlier, McCarty) were well on the way to demonstrate DNA's genetic ability.

Delbrück, Luria, and Hershey established a course in bacteriophage genetics at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Long Island, New York, in 1945. The Phage Group in the United States sparked molecular biology's early development. Delbrück received the Nobel Physiology or Medicine Award in 1969, a prize that was shared with Luria and Hershey "for their findings regarding the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses." "The honor in the first place goes to Delbrück," the committee said, who transformed bacteriophage research from vague empiricism to an exact science." He analyzed and characterized the conditions for precise measurement of biological reactions. He developed the quantitative techniques and established the statistical criteria for analysis, making the subsequent penetrating studies possible together with Luria. Delbrück's and Luria's forte is, perhaps, purely theoretical research, but Hershey, above all, is an eminently gifted experimenter. In this regard, the three of them complement each other well." The Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize was also given to Delbrück and Luria this year. Delbrück had returned to Caltech as a biology professor and remained there for the remainder of his career in late 1947 as Vanderbilt ran out of funds to keep him. In the meantime, he established the University of Cologne's molecular genetics center.