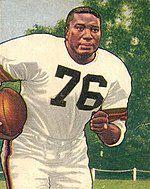

Marion Motley

Marion Motley was born in Georgia, United States on June 5th, 1920 and is the Football Player. At the age of 79, Marion Motley biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 79 years old, Marion Motley has this physical status:

Marion Motley (June 5, 1920 – June 27, 1999) was an American football fullback and linebacker for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL).

He was a leading pass-blocker and rusher in the late 1940s and early 1950s and ended his career with an average of 5.7 yards per carry, a record for running backs that still stands.

Motley, a versatile player with both quickness and size, was a force on both offense and defense.

In September 1946, Motley and teammate Bill Willis became the first two African-Americans to play professional football in the modern era, breaking the colour barrier along with teammate Bill Willis in Canton, Ohio.

In the 1930s, he played football through high school and college before enlisting in the service during World War II.

He served with a service team coached by Paul Brown while serving in the United States Navy in 1944.

Following the war, he returned to Canton before Brown asked him to try out for the Cleveland Browns, a team he was coaching in the newly formed AAFC.

Motley joined the team in 1946 and became a pillar of Cleveland's resurgent 1940s glory.

Before the league was disbanded, the team won four AAFC championships and the Browns were absorbed by the more established NFL.

In 1948 and 1950, Motley was the AAFC's top rusher and the NFL champion, as the Browns captured their second championship. Throughout their careers, Motley and a fellow black teammate Bill Willis battled bigotry.

Despite the fact that the color barrier was broken in all major American sports by 1950, the guys were yelled abuse on the track and racial discrimination out of it.

"They discovered out that while they were calling us niggers and alligator bait, Willis was running for touchdowns and Willis was knocking the shit out of them," Motley once said."

"They stopped calling us names and started trying to keep up with us." Brown did not tolerate bigotry within the team, and so it was solely focused on winning. Motley left the Browns in 1953 after being slowed by knee injuries.

In 1955 as a linebacker for the Pittsburgh Steelers, he attempted a comeback but was released before the year's end.

He began seeking a teaching career, but was refused by the Browns and other teams he encountered.

He attributed his struggles in finding a job in football to racial discrimination, saying that teams were hesitant to recruit a black coach.

In 1968, Motley was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Later life and death

Motley contacted Brown about a coaching role with the team after completing his playing career for good. Brown, on the other hand, dismissed his overtures, saying that Motley should look for jobs at a steel mill rather than wrestling a football team – the very sport footballer was born with. He served as a whisky salesman in the early 1960s, but was unable to find coaching opportunities in the NFL. He had occasional scouting assignments for the Browns, but as the Civil Rights Movement gained traction in 1965, he released a statement saying that he had been refused a permanent coaching position by the team's multiple times. He started to teach in 1964, but was told there were no open positions. Bob Nussbaumer was later hired as an assistant by the Browns, who then recruited him as an assistant. "I began to wonder if the primary reason, whether or not the time is ripe to recruit a Negro coach in Cleveland on the professional level," he wrote. The Browns' owner, Art Modell, responded by saying that the team filled its coaching positions based on skills and experience, not race. "We are represented by scouts at every major Negro school." We now have 12 Negroes signed to the 1965 season, according to he.

When Graham was head coach for the Washington Redskins in the late 1960s, Motley had requested Otto Graham for a job with the Washington Redskins, but he was turned away once more. In 1967, Motley was hired by the Cleveland Dare Devils, an all-girl professional football team. The Cleveland theatrical agent Syd Freedman's struggled to drum up excitement in a women's league by 1969, when the team had only appeared in a few exhibition games. Later in life, Motley served for the United States postal service in Cleveland, Harry Miller Excavating Suffield, Ohio, the Ohio Lottery, and the Ohio Department of Youth Services in Akron. He died in 1999, twenty-two days after his 79th birthday, of prostate cancer.

Early years and college career

Motley was born in Leesburg, Georgia, and raised in Canton, Ohio, where his family moved when he was three years old. Motley attended Canton McKinley High School, where he competed in both elementary and junior high schools in Canton. During his time as a football fullback, he was also an outstanding player, and the McKinley Bulldogs set a record of 25–3 wins-loss during his time in office. The team's three losses were all against Canton's key rivals, a Massillon Washington High School team led by coach Paul Brown.

Motley enrolled in 1939 at South Carolina State College, a historically black academy in Orangeburg, South Carolina, after he graduated. He came from Nevada before his sophomore year, where he spent time on the football team from 1941 to 1943. Motley was a punishing fullback for the Wolf Pack as a strong West Coast team, including USF, Santa Clara, and St. Mary's. Since dropping out of school, he suffered a knee injury in 1943 and returned to Canton to work.

Military and professional career

Motley joined the United States Navy in 1944 and was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station as the United States' involvement in World War II increased. He played for the Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets, a military team coached by Paul Brown, who was in the Navy during an extended leave from his service as the head coach of The Ohio State University's football team. At Great Lakes, Motley was both a fullback and linebacker, and he was a key figure in the team's offense and defense. In 1945, the highlight of his time at Great Lakes was a 39–7 win over Notre Dame. Before the game, Motley was eligible for discharge – it was the season's final match and the last military game of World War II – but he continued to play. Motley put up an impressive showing, thanks in part to Brown's attempt with a new tactic: a delayed handoff later called the draw play.

After the war, Motley returned to Canton and began working at a steel mill, aiming to return to Reno in 1946 to complete his degree. Paul Brown was assisting a team in the recent All-America Football Conference (AAFC) called the Cleveland Browns that summer. Motley wrote to Brown and asked for a try out, but Brown turned down, saying he already had all the fullbacks he needed. Brown, however, welcomed Bill Willis, another African-American actor, to try out for the team at its training camp in Bowling Green, Ohio, right away at the start of August. Brown invited Motley to visit us ten days later. Later, Motley said, "They [Willis] felt they needed a roommate." "I don't think they felt like I'd be a member of the team." I'm glad I was able to deceive them."

Both Motley and Willis joined the team and became two of the first African-Americans to play professional football in the modern age. Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, the Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League, were among the few black players in pro football earlier this year: Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. A seven months before Jackie Robinson was promoted from the Class AAA Montreal Royals to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, the four men broke football's color barrier. Motley said the Browns would be his only chance to make a career out of football. "I knew this was the one big chance in my life to rise above the steel mill life, and I wanted to take it," he said.

Motley was signed to a $4,500 a year (2021 dollars) per year. With the Browns, he joined a potent offense led by quarterback Otto Graham, tackle and placekicker Lou Groza, and receivers Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie. He was a force to be reckoned with in the AAFC, and he helped the team win every championship in the league's four years from 1946 to 1949. He had a combination of quickness and strength, which helped him plow through tacklers. He was also a good pass blocker and played on defense as a linebacker. In his first season, Motley ran for an average of 8.2 yards per carry. His forte was the trap game, a scheme in which a defensive lineman was allowed to come across the line of scrimmage unblocked, opening up space for Motley to run. As the Browns posted a perfect 15-0 record in 1948, he led the league in rushing. After the 1949 season, he was the AAFC's all-time rush leader and the Browns were absorbed into the more established National Football League (NFL). With Motley rushing for a total of 3,024 yards, the Browns had a 47–4-3 overall regular-season victory-loss record during the AAFC years.

Motley, like other black players in the 1940s and 1950s, exhibited bigotry both on and off the track. Paul Brown will not tolerate misogyny within the team; he wanted to win and would not let anything get in his way. However, Motley and Willis were occasionally stepped on and called names during games. "Sometimes I wanted to just kill some of those guys, and the cops would just stand right there," Motley said many years later. "They'd see those guys stepping on us and heard them saying things and then turning their backs to us." For two to three years, they didn't know what kind of players they were." After receiving threatening letters, Motley and Willis did not attend one game against the Miami Seahawks in the Browns' early years. The team was not welcome at the hotel where they were staying in Miami. Motley and Willis were told again. Brown threatened to relocate the entire staff, but the hotel's leadership reacted angrily.

After the war, attitudes toward race in America began to shift, sparking political and political turmoil, and prompted people to think about the future with more enthusiasm and optimism. Despite the fact that change was slow and rhetorically motivated hostility lasted for many years, the color barrier in all major sports was busted by 1950. Many of Motley and Willis' teammates were used to playing with black players in college, where teams were integrated into most of the country. During several of the Browns' early games, the presence of Motley and Willis, meanwhile, resulted in good attendance at many of the Browns' early games, as large black audiences attended them. According to one, 10,000 black fans attended the Browns' first game.

The Browns won the NFL championship in 1950, their first season in the league, aided by Motley's quickness and size. Motley averaged over 17 yards per rush against the Pittsburgh Steelers in October 1950, a record that stood for more than five decades, with 188 yards on 11 attempts. Quarterback Michael Vick of the Atlanta Falcons rushed for 173 yards on ten attempts against the Minnesota Vikings in December 2002, eclipsing Motley's average. In the game, Motley had a 69-yard rushing and 33-yard receiving touchdowns. Although Motley did not participate in the Browns' championship game over the Los Angeles Rams, he led the league in rushing with 810 yards in 1950, despite averageveraging fewer than 12 carries per game. He was a unanimous first-team All-Pro pick.

Motley's hard-hitting, up-the-middle running style began to show physically by the 1951 season. He suffered a knee injury in training camp and was getting older; by the time the season was officially underway, he was 31. Motley's season began with 273 yards and one touchdown, an unusually poor number. Despite Motley's woes, the Browns won the American Conference for the second time after winning the American Conference with an 11–1 record. Cleveland, on the other hand, lost the title game to the Rams 24–17. Motley had only five runs and 23 yards.

In 1952, Motley's knees began to bother him. Although he showed occasional signs of his old form this season, it became abundantly evident to the Browns' coaching staff that he was no longer in his prime. Motley ended the year with 444 yards of rushing and 4.3 yards per carry, a career low. The Browns finished 8-0 on the year, but they still took the conference championship and a second spot in the NFL championship game. In the match against the Detroit Lions, Motley did well, rushing for 95 yards. The Browns, on the other hand, lost 17–7.

The 1953 season was no better for Motley, whose ability was limited due to sickness. Cleveland finished 11–1 record and defeated Detroit in the championship for the second year in a row. The Browns relied on Otto Graham's departure to Lavelli and receiver Ray Renfro, who also lined up as a running back, as Motley's production decreased. This year, Motley did not appear in the championship game, yet another loss to the Lions.

Motley thought he'd return to play a ninth season in 1954, but he didn't turn up to training camp to prove it. Paul Brown, on the other hand, believed otherwise. Motley, who suffered from injuries and 34 years old, was forced to leave before the season began, after Brown said he would not be cut from the team otherwise. Brown wrote at the time, "Marion knew that his knee was weak and did not believe it was coming back." "He was one of the finest fullbacks in his prime, the kind that comes along every other lifetime." I'll certainly never forget any of his plays, and I'd imagine Cleveland football fans feel the same."

Since the Browns, who still had rights to Motley under his contract, traded him to the Pittsburgh Steelers for Ed Modzelewski, Motley started a comeback in 1955. He appeared in seven games as a linebacker in Pittsburgh, but the Steelers cut him before the season ended. Motley had rushed for 4,720 yards and averaged 5.7 yards per carry in his eight years in the NFL and NFL. His running backs career average is still an all-time record.