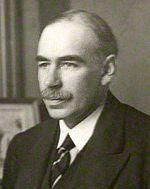

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes was born in Cambridge, England, United Kingdom on June 5th, 1883 and is the Economist. At the age of 62, John Maynard Keynes biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 62 years old, John Maynard Keynes physical status not available right now. We will update John Maynard Keynes's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

In October 1906 Keynes began his Civil Service career as a clerk in the India Office. He enjoyed his work at first, but by 1908 had become bored and resigned his position to return to Cambridge and work on probability theory, through a lectureship in economics at first funded personally by economists Alfred Marshall and Arthur Pigou; he became a fellow of King's College in 1909.

By 1909 Keynes had also published his first professional economics article in The Economic Journal, about the effect of a recent global economic downturn on India. He founded the Political Economy Club, a weekly discussion group. Keynes's earnings rose further as he began to take on pupils for private tuition.

In 1911 Keynes was made the editor of The Economic Journal. By 1913 he had published his first book, Indian Currency and Finance. He was then appointed to the Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance – the same topic as his book – where Keynes showed considerable talent at applying economic theory to practical problems. His written work was published under the name "J M Keynes", though to his family and friends he was known as Maynard. (His father, John Neville Keynes, was also always known by his middle name).

The British Government called on Keynes's expertise during the First World War. While he did not formally re-join the civil service in 1914, Keynes travelled to London at the government's request a few days before hostilities started. Bankers had been pushing for the suspension of specie payments – the gold equivalent of banknotes — but with Keynes's help the Chancellor of the Exchequer (then Lloyd George) was persuaded that this would be a bad idea, as it would hurt the future reputation of the city if payments were suspended before it was necessary.

In January 1915 Keynes took up an official government position at the Treasury. Among his responsibilities were the design of terms of credit between Britain and its continental allies during the war and the acquisition of scarce currencies. According to economist Robert Lekachman, Keynes's "nerve and mastery became legendary" because of his performance of these duties, as in the case where he managed to assemble – with difficulty – a small supply of Spanish pesetas.

The secretary of the Treasury was delighted to hear Keynes had amassed enough to provide a temporary solution for the British Government. But Keynes did not hand the pesetas over, choosing instead to sell them all to break the market: his boldness paid off, as pesetas then became much less scarce and expensive.

On the introduction of military conscription in 1916, he applied for exemption as a conscientious objector, which was effectively granted conditional upon continuing his government work.

In the 1917 King's Birthday Honours, Keynes was appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath for his wartime work, and his success led to the appointment that had a huge effect on Keynes's life and career; Keynes was appointed financial representative for the Treasury to the 1919 Versailles peace conference. He was also appointed Officer of the Belgian Order of Leopold.

Keynes's experience at Versailles was influential in shaping his future outlook, yet it was not a successful one. Keynes's main interest had been in trying to prevent Germany's compensation payments being set so high it would traumatize innocent German people, damage the nation's ability to pay and sharply limit its ability to buy exports from other countries – thus hurting not just Germany's economy but that of the wider world.

Unfortunately for Keynes, conservative powers in the coalition that emerged from the 1918 coupon election were able to ensure that both Keynes himself and the Treasury were largely excluded from formal high-level talks concerning reparations. Their place was taken by the Heavenly Twins – the judge Lord Sumner and the banker Lord Cunliffe whose nickname derived from the "astronomically" high war compensation they wanted to demand from Germany. Keynes was forced to try to exert influence mostly from behind the scenes.

The three principal players at Versailles were Britain's Lloyd George, France's Clemenceau and America's President Wilson. It was only Lloyd George to whom Keynes had much direct access; until the 1918 election he had some sympathy with Keynes's view but while campaigning had found his speeches were well received by the public only if he promised to harshly punish Germany, and had therefore committed his delegation to extracting high payments.

Lloyd George did, however, win some loyalty from Keynes with his actions at the Paris conference by intervening against the French to ensure the dispatch of much-needed food supplies to German civilians. Clemenceau also pushed for substantial reparations, though not as high as those proposed by the British, while on security grounds, France argued for an even more severe settlement than Britain.

Wilson initially favoured relatively lenient treatment of Germany – he feared too harsh conditions could foment the rise of extremism and wanted Germany to be left sufficient capital to pay for imports. To Keynes's dismay, Lloyd George and Clemenceau were able to pressure Wilson to agree to include pensions in the reparations bill.

Towards the end of the conference, Keynes came up with a plan that he argued would not only help Germany and other impoverished central European powers but also be good for the world economy as a whole. It involved the radical writing down of war debts, which would have had the possible effect of increasing international trade all round, but at the same time thrown over two-thirds of the cost of European reconstruction on the United States.

Lloyd George agreed it might be acceptable to the British electorate. However, America was against the plan; the US was then the largest creditor, and by this time Wilson had started to believe in the merits of a harsh peace and thought that his country had already made excessive sacrifices. Hence despite his best efforts, the result of the conference was a treaty which disgusted Keynes both on moral and economic grounds and led to his resignation from the Treasury.

In June 1919 he turned down an offer to become chairman of the British Bank of Northern Commerce, a job that promised a salary of £2000 in return for a morning per week of work.

Keynes's analysis on the predicted damaging effects of the treaty appeared in the highly influential book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, published in 1919. This work has been described as Keynes's best book, where he was able to bring all his gifts to bear – his passion as well as his skill as an economist. In addition to economic analysis, the book contained appeals to the reader's sense of compassion:

Also present was striking imagery such as "year by year Germany must be kept impoverished and her children starved and crippled" along with bold predictions which were later justified by events:

Keynes's followers assert that his predictions of disaster were borne out when the German economy suffered the hyperinflation of 1923, and again by the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the outbreak of the Second World War. However, historian Ruth Henig claims that "most historians of the Paris peace conference now take the view that, in economic terms, the treaty was not unduly harsh on Germany and that, while obligations and damages were inevitably much stressed in the debates at Paris to satisfy electors reading the daily newspapers, the intention was quietly to give Germany substantial help towards paying her bills, and to meet many of the German objections by amendments to the way the reparations schedule was in practice carried out".

Only a small fraction of reparations was ever paid. In fact, historian Stephen A. Schuker demonstrates in American 'Reparations' to Germany, 1919–33, that the capital inflow from American loans substantially exceeded German out payments so that, on a net basis, Germany received support equal to four times the amount of the post-Second World War Marshall Plan.

Schuker also shows that, in the years after Versailles, Keynes became an informal reparations adviser to the German government, wrote one of the major German reparation notes, and supported the hyperinflation on political grounds. Nevertheless, The Economic Consequences of the Peace gained Keynes international fame, even though it also caused him to be regarded as anti-establishment – it was not until after the outbreak of the Second World War that Keynes was offered a directorship of a major British Bank, or an acceptable offer to return to government with a formal job. However, Keynes was still able to influence government policy making through his network of contacts, his published works and by serving on government committees; this included attending high-level policy meetings as a consultant.

Keynes had completed his A Treatise on Probability before the war but published it in 1921. The work was a notable contribution to the philosophical and mathematical underpinnings of probability theory, championing the important view that probabilities were no more or less than truth values intermediate between simple truth and falsity. Keynes developed the first upper-lower probabilistic interval approach to probability in chapters 15 and 17 of this book, as well as having developed the first decision weight approach with his conventional coefficient of risk and weight, c, in chapter 26. In addition to his academic work, the 1920s saw Keynes active as a journalist selling his work internationally and working in London as a financial consultant. In 1924 Keynes wrote an obituary for his former tutor Alfred Marshall which Joseph Schumpeter called "the most brilliant life of a man of science I have ever read."Mary Paley Marshall was "entranced" by the memorial, while Lytton Strachey rated it as one of Keynes's "best works".

In 1922 Keynes continued to advocate reduction of German reparations with A Revision of the Treaty. He attacked the post-World War I deflation policies with A Tract on Monetary Reform in 1923 – a trenchant argument that countries should target stability of domestic prices, avoiding deflation even at the cost of allowing their currency to depreciate. Britain suffered from high unemployment through most of the 1920s, leading Keynes to recommend the depreciation of sterling to boost jobs by making British exports more affordable. From 1924 he was also advocating a fiscal response, where the government could create jobs by spending on public works. During the 1920s Keynes's pro stimulus views had only limited effect on policy makers and mainstream academic opinion – according to Hyman Minsky one reason was that at this time his theoretical justification was "muddled". The Tract had also called for an end to the gold standard. Keynes advised it was no longer a net benefit for countries such as Britain to participate in the gold standard, as it ran counter to the need for domestic policy autonomy. It could force countries to pursue deflationary policies at exactly the time when expansionary measures were called for to address rising unemployment. The Treasury and Bank of England were still in favour of the gold standard and in 1925 they were able to convince the then Chancellor Winston Churchill to re-establish it, which had a depressing effect on British industry. Keynes responded by writing The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill and continued to argue against the gold standard until Britain finally abandoned it in 1931.

Keynes had begun a theoretical work to examine the relationship between unemployment, money, and prices back in the 1920s. The work, Treatise on Money, was published in 1930 in two volumes. A central idea of the work was that if the amount of money being saved exceeds the amount being invested – which can happen if interest rates are too high – then unemployment will rise. This is in part a result of people not wanting to spend too high a proportion of what employers pay out, making it difficult, in aggregate, for employers to make a profit. Another key theme of the book is the unreliability of financial indices for representing an accurate – or indeed meaningful – indication of general shifts in purchasing power of currencies over time. In particular, he criticised the justification of Britain's return to the gold standard in 1925 at pre-war valuation by reference to the wholesale price index. He argued that the index understated the effects of changes in the costs of services and labour.

Keynes was deeply critical of the British government's austerity measures during the Great Depression. He believed that budget deficits during recessions were a good thing and a natural product of an economic slump. He wrote, "For Government borrowing of one kind or another is nature's remedy, so to speak, for preventing business losses from being, in so severe a slump as the present one, so great as to bring production altogether to a standstill."

At the height of the Great Depression, in 1933, Keynes published The Means to Prosperity, which contained specific policy recommendations for tackling unemployment in a global recession, chiefly counter-cyclical public spending. The Means to Prosperity contains one of the first mentions of the multiplier effect. While it was addressed chiefly to the British Government, it also contained advice for other nations affected by the global recession. A copy was sent to the newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other world leaders. The work was taken seriously by both the American and British governments, and according to Robert Skidelsky, helped pave the way for the later acceptance of Keynesian ideas, though it had little immediate practical influence. In the 1933 London Economic Conference opinions remained too diverse for a unified course of action to be agreed upon.

Keynesian-like policies were adopted by Sweden and Germany, but Sweden was seen as too small to command much attention, and Keynes was deliberately silent about the successful efforts of Germany as he was dismayed by its imperialist ambitions and its treatment of Jews. Apart from Great Britain, Keynes's attention was primarily focused on the United States. In 1931, he received considerable support for his views on counter-cyclical public spending in Chicago, then America's foremost center for economic views alternative to the mainstream. However, orthodox economic opinion remained generally hostile regarding fiscal intervention to mitigate the depression, until just before the outbreak of war. In late 1933 Keynes was persuaded by Felix Frankfurter to address President Roosevelt directly, which he did by letters and face to face in 1934, after which the two men spoke highly of each other. However, according to Skidelsky, the consensus is that Keynes's efforts began to have a more than marginal influence on US economic policy only after 1939.

Keynes's magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money was published in 1936. It was researched and indexed by one of Keynes's favourite students, later the economist David Bensusan-Butt. The work served as a theoretical justification for the interventionist policies Keynes favoured for tackling a recession. Although Keynes stated in his preface that his General Theory was only secondarily concerned with the "applications of this theory to practice," the circumstances of its publication were such that his suggestions shaped the course of the 1930s. In addition, Keynes introduced the world to a new interpretation of taxation: since the legal tender is now defined by the state, inflation becomes "taxation by currency depreciation". This hidden tax meant a) that the standard of value should be governed by deliberate decision; and (b) that it was possible to maintain a middle course between deflation and inflation. This novel interpretation was inspired by the desperate search for control over the economy which permeated the academic world after the Depression. The General Theory challenged the earlier neoclassical economic paradigm, which had held that provided it was unfettered by government interference, the market would naturally establish full employment equilibrium. In doing so Keynes was partly setting himself against his former teachers Marshall and Pigou. Keynes believed the classical theory was a "special case" that applied only to the particular conditions present in the 19th century, his theory being the general one. Classical economists had believed in Say's law, which, simply put, states that "supply creates its demand", and that in a free market workers would always be willing to lower their wages to a level where employers could profitably offer them jobs.

An innovation from Keynes was the concept of price stickiness – the recognition that in reality workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue that it is rational for them to do so. Due in part to price stickiness, it was established that the interaction of "aggregate demand" and "aggregate supply" may lead to stable unemployment equilibria – and in those cases, it is on the state, not the market, that economies must depend for their salvation. In contrast, Keynes argued that demand is what creates supply and not the other way around. He questioned Say's Law by asking what would happen if the money that is being given to individuals is not finding its way back into the economy and is saved instead? He suggested the result would be a recession. To tackle the fear of a recession Say's Law suggests government intervention. This government intervention can be used to prevent any further increase in savings in the form of a decreased interest rate. Decreasing the interest rate will encourage people to start spending and investing again, or so it is stated by Say's Law. The reason behind this is that when there is little investing, savings start to accumulate and reach a stopping point in the flow of money. During the normal economic activity, it would be justified to have savings because they can be given out as loans but in this case, there is little demand for them, so they are doing no good for the economy. The supply of savings then exceeds the demand for loans and the result is lower prices or lower interest rates. Thus, the idea is that the money that was once saved is now re-invested or spent, assuming lower interest rates appeal to consumers. To Keynes, however, this was not always the case, and it couldn't be assumed that lower interest rates would automatically encourage investment and spending again since there is no proven link between the two.

The General Theory argues that demand, not supply, is the key variable governing the overall level of economic activity. Aggregate demand, which equals total un-hoarded income in a society, is defined by the sum of consumption and investment. In a state of unemployment and unused production capacity, one can enhance employment and total income only by first increasing expenditures for either consumption or investment. Without government intervention to increase expenditure, an economy can remain trapped in a low-employment equilibrium. The demonstration of this possibility has been described as the revolutionary formal achievement of the work. The book advocated activist economic policy by government to stimulate demand in times of high unemployment, for example by spending on public works. "Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth," he wrote in 1928. "With men and plants unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford these new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them."

The General Theory is often viewed as the foundation of modern macroeconomics. Few senior American economists agreed with Keynes through most of the 1930s. Yet his ideas were soon to achieve widespread acceptance, with eminent American professors such as Alvin Hansen agreeing with the General Theory before the outbreak of World War II.

Keynes himself had only limited participation in the theoretical debates that followed the publication of the General Theory as he suffered a heart attack in 1937, requiring him to take long periods of rest. Among others, Hyman Minsky and Post-Keynesian economists have argued that as result, Keynes's ideas were diluted by those keen to compromise with classical economists or to render his concepts with mathematical models like the IS–LM model (which, they argue, distort Keynes's ideas). Keynes began to recover in 1939, but for the rest of his life his professional energies were directed largely towards the practical side of economics: the problems of ensuring optimum allocation of resources for the war efforts, post-war negotiations with America, and the new international financial order that was presented at the Bretton Woods Conference.

In the General Theory and later, Keynes responded to the socialists who argued, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s, that capitalism caused war. He argued that if capitalism were managed domestically and internationally (with coordinated international Keynesian policies, an international monetary system that did not pit the interests of countries against one another, and a high degree of freedom of trade), then this system of managed capitalism could promote peace rather than conflict between countries. His plans during World War II for post-war international economic institutions and policies (which contributed to the creation at Bretton Woods of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and later to the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and eventually the World Trade Organization) were aimed to give effect to this vision.

Although Keynes has been widely criticised – especially by members of the Chicago school of economics – for advocating irresponsible government spending financed by borrowing, in fact he was a firm believer in balanced budgets and regarded the proposals for programs of public works during the Great Depression as an exceptional measure to meet the needs of exceptional circumstances.

During the Second World War, Keynes argued in How to Pay for the War, published in 1940, that the war effort should be largely financed by higher taxation and especially by compulsory saving (essentially workers lending money to the government), rather than deficit spending, to avoid inflation. Compulsory saving would act to dampen domestic demand, assist in channelling additional output towards the war efforts, would be fairer than punitive taxation and would have the advantage of helping to avoid a post-war slump by boosting demand once workers were allowed to withdraw their savings. In September 1941 he was proposed to fill a vacancy in the Court of Directors of the Bank of England, and subsequently carried out a full term from the following April. In June 1942, Keynes was rewarded for his service with a hereditary peerage in the King's Birthday Honours. On 7 July his title was gazetted as "Baron Keynes, of Tilton, in the County of Sussex" and he took his seat in the House of Lords on the Liberal Party benches.

By contrast, in his capacity as advisor on the Indian Financial and Monetary Affairs for the British Government, there is evidence that Keynes advocated "profit inflation" in order to finance war spending by the Allied forces in Bengal. This deliberate inflationary policy, which caused a sixfold increase in the price of rice, contributed to the 1943 Bengal famine.

As the Allied victory began to look certain, Keynes was heavily involved, as leader of the British delegation and chairman of the World Bank commission, in the mid-1944 negotiations that established the Bretton Woods system. The Keynes plan, concerning an international clearing-union, argued for a radical system for the management of currencies. He proposed the creation of a common world unit of currency, the bancor, and new global institutions – a world central bank and the International Clearing Union. Keynes envisaged these institutions managing an international trade and payments system with strong incentives for countries to avoid substantial trade deficits or surpluses. The USA's greater negotiating strength, however, meant that the outcomes accorded more closely to the more conservative plans of Harry Dexter White. According to US economist J. Bradford DeLong, on almost every point where he was overruled by the Americans, Keynes was later proven correct by events.

The two new institutions, later known as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), were founded as a compromise that primarily reflected the American vision. There would be no incentives for states to avoid a large trade surplus; instead, the burden for correcting a trade imbalance would continue to fall only on the deficit countries, which Keynes had argued were least able to address the problem without inflicting economic hardship on their populations. Yet, Keynes was still pleased when accepting the final agreement, saying that if the institutions stayed true to their founding principles, "the brotherhood of man will have become more than a phrase."

After the war, Keynes continued to represent the United Kingdom in international negotiations despite his deteriorating health. He succeeded in obtaining preferential terms from the United States for new and outstanding debts to facilitate the rebuilding of the British economy.

Just before his death in 1946, Keynes told Henry Clay, a professor of social economics and advisor to the Bank of England, of his hopes that Adam Smith's "invisible hand" could help Britain out of the economic hole it was in: "I find myself more and more relying for a solution of our problems on the invisible hand which I tried to eject from economic thinking twenty years ago."