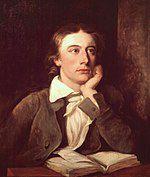

John Keats

John Keats was born in Moorgate, England, United Kingdom on October 31st, 1795 and is the Poet. At the age of 25, John Keats biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 25 years old, John Keats physical status not available right now. We will update John Keats's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

From 1814 Keats had two bequests, held in trust for him until his 21st birthday. £800 was willed by his grandfather John Jennings. Also Keats's mother left a legacy of £8000 to be equally divided among her living children. It seems he was not told of the £800 and probably knew nothing of it as he never applied for it. Historically, blame has often been laid on Abbey as legal guardian, but he may also have been unaware of it. William Walton, solicitor for Keats's mother and grandmother, definitely knew and had a duty of care to relay the information to Keats. It seems he did not, though it would have made a critical difference to the poet's expectations. Money was always a great concern and difficulty, as he struggled to stay out of debt and make his way in the world independently.

Having finished his apprenticeship with Hammond, Keats registered as a medical student at Guy's Hospital (now part of King's College London) and began studying there in October 1815. Within a month, he was accepted as a dresser at the hospital assisting surgeons during operations – the equivalent of a junior house surgeon today. It was a significant promotion, that marked a distinct aptitude for medicine; and it brought greater responsibility and a heavier workload. Keats's long and expensive medical training with Hammond and at Guy's Hospital led his family to assume he would pursue a lifelong career in medicine, assuring financial security, and it seems that, at this point, Keats had a genuine desire to become a doctor. He lodged near the hospital, at 28 St Thomas's Street in Southwark, with other medical students, including Henry Stephens who gained fame as an inventor and ink magnate.

Keats's training took up increasing amounts of his writing time and he became increasingly ambivalent about it. He felt he was facing a stark choice. He had written his first extant poem, "An Imitation of Spenser," in 1814, when he was 19. Now, strongly drawn by ambition, inspired by fellow poets such as Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron, and beleaguered by family financial crises, he suffered periods of depression. His brother George wrote that John "feared that he should never be a poet, & if he was not he would destroy himself." In 1816, Keats received his apothecary's licence, which made him eligible to practise as an apothecary, physician and surgeon, but before the end of the year he had informed his guardian that he resolved to be a poet, not a surgeon.

Although he continued his work and training at Guy's, Keats devoted more and more time to the study of literature, experimenting with verse forms, particularly the sonnet. In May 1816, Leigh Hunt agreed to publish the sonnet "O Solitude" in his magazine The Examiner, a leading liberal magazine of the day. This was the first appearance of Keats's poetry in print; Charles Cowden Clarke called it his friend's red letter day, first proof that Keats' ambitions were valid. Among his poems of 1816 was To My Brothers. That summer, Keats went with Clarke to the seaside town of Margate to write. There he began "Calidore" and initiated an era of great letter writing. On returning to London, he took lodgings at 8 Dean Street, Southwark, and braced himself to study further for membership of the Royal College of Surgeons.

In October 1816, Clarke introduced Keats to the influential Leigh Hunt, a close friend of Byron and Shelley. Five months later came the publication of Poems, the first volume of Keats's verse, which included "I stood tiptoe" and "Sleep and Poetry," both strongly influenced by Hunt. The book was a critical failure, arousing little interest, although Reynolds reviewed it favourably in The Champion. Clarke commented that the book "might have emerged in Timbuctoo." Keats's publishers, Charles and James Ollier, felt ashamed of it. Keats immediately changed publishers to Taylor and Hessey in Fleet Street. Unlike the Olliers, Keats's new publishers were enthusiastic about his work. Within a month of the publication of Poems they were planning a new Keats volume and had paid him an advance. Hessey became a steady friend to Keats and made the company's rooms available for young writers to meet. Their publishing lists came to include Coleridge, Hazlitt, Clare, Hogg, Carlyle and Charles Lamb.

Through Taylor and Hessey, Keats met their Eton-educated lawyer, Richard Woodhouse, who advised them on literary as well as legal matters and was deeply impressed by Poems. Although he noted that Keats could be "wayward, trembling, easily daunted," Woodhouse was convinced of Keats's genius, a poet to support as he became one of England's greatest writers. Soon after they met, the two became close friends, and Woodhouse started to collect Keatsiana, documenting as much as he could about the poetry. This archive survives as one of the main sources of information on Keats's work. Andrew Motion represents him as Boswell to Keats's Johnson, ceaselessly promoting his work, fighting his corner and spurring his poetry to greater heights. In later years, Woodhouse was one of the few to accompany Keats to Gravesend, Kent to embark on his final trip to Rome.

Despite the bad reviews of Poems, Hunt published the essay "Three Young Poets" (Shelley, Keats, and Reynolds) and the sonnet "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer," foreseeing great things to come. He introduced Keats to many prominent men in his circle, including the editor of The Times, Thomas Barnes; the writer Lamb]]; the conductor Vincent Novello; and the poet John Hamilton Reynolds, who would become a close friend. Keats also met regularly with William Hazlitt, a powerful literary figure of the day. It was a turning point for Keats, establishing him in the public eye as a figure in what Hunt termed "a new school of poetry". At this time Keats wrote to his friend Bailey, "I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Heart's affections and the truth of the imagination. What imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth." This passage would eventually be transmuted into the concluding lines of "Ode on a Grecian Urn": "'Beauty is truth, truth beauty' – that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know". In early December 1816, under the heady influence of his artistic friends, Keats told Abbey he had decided to give up medicine in favour of poetry, to Abbey's fury. Keats had spent a great deal on his medical training, and despite his state of financial hardship and indebtedness, made large loans to friends such as the painter Benjamin Haydon. Keats would go on to lend £700 to his brother George. By lending so much, Keats could no longer cover the interest of his own debts.

Having left his training at the hospital, suffering from a succession of colds, and unhappy with living in damp rooms in London, Keats moved with his brothers into rooms at 1 Well Walk in the village of Hampstead in April 1817. There John and George nursed their tubercular brother Tom. The house was close to Hunt and others of his circle in Hampstead, and to Coleridge, respected elder of the first wave of Romantic poets, then living in Highgate. On 11 April 1818, Keats reported that he and Coleridge had taken a long walk on Hampstead Heath. In a letter to his brother George, he wrote that they had talked about "a thousand things,... nightingales, poetry, poetical sensation, metaphysics." Around this time he was introduced to Charles Wentworth Dilke and James Rice.

In June 1818, Keats began a walking tour of Scotland, Ireland and the Lake District with Charles Armitage Brown. Keats's brother George and his wife Georgina accompanied them to Lancaster and then continued to Liverpool, from where they migrated to America, living in Ohio and Louisville, Kentucky until 1841, when George's investments failed. Like Keats's other brother, they both died penniless and racked by tuberculosis, for which there was no effective treatment until the next century. In July, while on the Isle of Mull, Keats caught a bad cold and "was too thin and fevered to proceed on the journey." After returning south in August, Keats continued to nurse Tom, so exposing himself to infection. Some have suggested this was when tuberculosis, his "family disease", took hold. "Consumption" was not identified as a disease with a single infectious origin until 1820. There was considerable stigma attached to it, as it was often tied with weakness, repressed sexual passion, or masturbation. Keats "refuses to give it a name" in his letters. Tom Keats died on 1 December 1818.

John Keats moved to the newly built Wentworth Place, owned by his friend Charles Armitage Brown. It was on the edge of Hampstead Heath, ten minutes' walk south of his old home in Well Walk. The winter of 1818–19, though a difficult period for the poet, marked the beginning of his annus mirabilis in which he wrote his most mature work. He had been inspired by a series of recent lectures by Hazlitt on English poets and poetic identity and had also met Wordsworth. Keats may have seemed to his friends to be living on comfortable means, but in reality he was borrowing regularly from Abbey and his friends.

He composed five of his six great odes at Wentworth Place in April and May and, although it is debated in which order they were written, "Ode to Psyche" opened the published series. According to Brown, "Ode to a Nightingale" was composed under a plum tree in the garden. Brown wrote, "In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. Keats felt a tranquil and continual joy in her song; and one morning he took his chair from the breakfast-table to the grass-plot under a plum-tree, where he sat for two or three hours. When he came into the house, I perceived he had some scraps of paper in his hand, and these he was quietly thrusting behind the books. On inquiry, I found those scraps, four or five in number, contained his poetic feelings on the song of our nightingale." Dilke, co-owner of the house, strenuously denied the story, printed in Richard Monckton Milnes' 1848 biography of Keats, dismissing it as 'pure delusion'.

"Ode on a Grecian Urn" and "Ode on Melancholy" were inspired by sonnet forms and probably written after "Ode to a Nightingale". Keats's new and progressive publishers Taylor and Hessey issued Endymion, which Keats dedicated to Thomas Chatterton, a work that he termed "a trial of my Powers of Imagination". It was damned by the critics, giving rise to Byron's quip that Keats was ultimately "snuffed out by an article", suggesting that he never truly got over it. A particularly harsh review by John Wilson Croker appeared in the April 1818 edition of the Quarterly Review. John Gibson Lockhart writing in Blackwood's Magazine, described Endymion as "imperturbable drivelling idiocy". With biting sarcasm, Lockhart advised, "It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop Mr John, back to plasters, pills, and ointment boxes." It was Lockhart at Blackwoods who coined the defamatory term "the Cockney School" for Hunt and his circle, which included both Hazlitt and Keats. The dismissal was as much political as literary, aimed at upstart young writers deemed uncouth for their lack of education, non-formal rhyming and "low diction". They had not attended Eton, Harrow or Oxbridge and they were not from the upper classes.

In 1819, Keats wrote "The Eve of St. Agnes", "La Belle Dame sans Merci", "Hyperion", "Lamia" and a play, Otho the Great (critically damned and not performed until 1950). The poems "Fancy" and "Bards of passion and of mirth" were inspired by the garden of Wentworth Place. In September, very short of money and in despair considering taking up journalism or a post as a ship's surgeon, he approached his publishers with a new book of poems. They were unimpressed with the collection, finding the presented versions of "Lamia" confusing, and describing "St Agnes" as having a "sense of pettish disgust" and "a 'Don Juan' style of mingling up sentiment and sneering" concluding it was "a poem unfit for ladies". The final volume Keats lived to see, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, was eventually published in July 1820. It received greater acclaim than had Endymion or Poems, finding favourable notices in both The Examiner and Edinburgh Review. It would come to be recognised as one of the most important poetic works ever published.

Wentworth Place now houses the Keats House museum.

Keats befriended Isabella Jones in May 1817, while on holiday in the village of Bo Peep, near Hastings. She is described as beautiful, talented and widely read, not of the top flight of society yet financially secure, an enigmatic figure who would become a part of Keats's circle. Throughout their friendship Keats never hesitated to own his sexual attraction to her, although they seemed to enjoy circling each other rather than offering commitment. He writes that he "frequented her rooms" in the winter of 1818–19, and in his letters to George says that he "warmed with her" and "kissed her". The trysts may have been a sexual initiation for Keats according to Bate and Robert Gittings. Jones inspired and was a steward of Keats's writing. The themes of "The Eve of St. Agnes" and "The Eve of St Mark" may well have been suggested by her, the lyric Hush, Hush! ["o sweet Isabel"] was about her, and that the first version of "Bright Star" may have originally been for her. In 1821, Jones was one of the first in England to be notified of Keats's death.

Letters and drafts of poems suggest that Keats first met Frances (Fanny) Brawne between September and November 1818. It is likely that the 18-year-old Brawne visited the Dilke family at Wentworth Place before she lived there. She was born in the hamlet of West End (now in the district of West Hampstead), on 9 August 1800. Like Keats's grandfather, her grandfather kept a London inn, and both lost several family members to tuberculosis. She shared her first name with both Keats's sister and mother, and had a talent for dress-making and languages as well as a natural theatrical bent. During November 1818 she developed an intimacy with Keats, but it was shadowed by the illness of Tom Keats, whom John was nursing through this period.

On 3 April 1819, Brawne and her widowed mother moved into the other half of Dilke's Wentworth Place, and Keats and Brawne were able to see each other every day. Keats began to lend Brawne books, such as Dante's Inferno, and they would read together. He gave her the love sonnet "Bright Star" (perhaps revised for her) as a declaration. It was a work in progress which he continued until the last months of his life, and the poem came to be associated with their relationship. "All his desires were concentrated on Fanny". From this point there is no further documented mention of Isabella Jones. Sometime before the end of June, he arrived at some sort of understanding with Brawne, far from a formal engagement as he still had too little to offer, with no prospects and financial stricture. Keats endured great conflict knowing his expectations as a struggling poet in increasingly hard straits would preclude marriage to Brawne. Their love remained unconsummated; jealousy for his 'star' began to gnaw at him. Darkness, disease and depression surrounded him, reflected in poems such as "The Eve of St. Agnes" and "La Belle Dame sans Merci" where love and death both stalk. "I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks;" he wrote to her, "...your loveliness, and the hour of my death".

In one of his many hundreds of notes and letters, Keats wrote to Brawne on 13 October 1819: "My love has made me selfish. I cannot exist without you – I am forgetful of every thing but seeing you again – my Life seems to stop there – I see no further. You have absorb'd me. I have a sensation at the present moment as though I was dissolving – I should be exquisitely miserable without the hope of soon seeing you ... I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion – I have shudder'd at it – I shudder no more – I could be martyr'd for my Religion – Love is my religion – I could die for that – I could die for you."

Tuberculosis took hold and he was advised by his doctors to move to a warmer climate. In September 1820 Keats left for Rome knowing he would probably never see Brawne again. After leaving he felt unable to write to her or read her letters, although he did correspond with her mother. He died there five months later. None of Brawne's letters to Keats survive.

It took a month for the news of his death to reach London, after which Brawne stayed in mourning for six years. In 1833, more than 12 years after his death, she married and went on to have three children; she outlived Keats by more than 40 years.