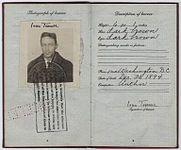

Jean Toomer

Jean Toomer was born in Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, United States on December 26th, 1894 and is the Novelist. At the age of 72, Jean Toomer biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 72 years old, Jean Toomer physical status not available right now. We will update Jean Toomer's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

After leaving college, Toomer returned to Washington, DC. He published some short stories and continued writing during the volatile social period following World War I. He worked for some months in a shipyard in 1919, then escaped to middle-class life. Labor strikes and race riots victimizing Black people occurred in numerous major industrial cities during the summer of 1919, which became known as Red Summer as a result. At the same time, it was a period of artistic ferment.

Toomer devoted eight months to the study of Eastern philosophies and continued to be interested in this subject. Some of his early writing was political, and he published three essays from 1919 to 1920 in the prominent socialist paper New York Call. His work drew from the socialist and "New Negro" movements of New York. He also read new American writing, such as Waldo Frank's Our America (1919). In 1919, he adopted "Jean Toomer" as his literary name, and it was the way he was known for most of his adult life.

By his early adult years, Toomer resisted racial classifications, wanting to be identified only as an American. He gained experience in both white and "colored" societies, and resisted being classified as a Negro writer. He grudgingly allowed his publisher of Cane to use that term to increase sales, as there was considerable interest in new Negro writers.

As Richard Eldridge has noted, Toomer "sought to transcend standard definitions of race. I think he never claimed that he was a white man. He always claimed that he was a representative of a new, emergent race that was a combination of various races. He averred this virtually throughout his life." William Andrews has noted he "was one of the first writers to move beyond the idea that any black ancestry makes you black."

In 1921 Toomer took a job for a few months as a principal at a new rural agricultural and manual labor college for Black people in Sparta, Georgia. Southern schools were continuing to recruit teachers from the North, although they had also trained generations of teachers since the Civil War. The school was in the center of Hancock County and the Black Belt 100 miles southeast of Atlanta, near where his father had lived. Exploring his father's roots in Hancock County, Toomer learned that he sometimes passed for white. Seeing the life of rural Blacks, racial segregation, and virtual labor peonage in the Deep South led Toomer to identify more strongly as African American and with his father's past.

Several lynchings of Black men took place in Georgia during 1921 and 1922, as whites continued to violently enforce white supremacy. In 1908 the state had ratified a constitution that disenfranchised most Black people and many poor whites by raising barriers to voter registration. Other former Confederate states had passed similar laws since 1890, led by Mississippi, and they maintained such disenfranchisement essentially into the late 1960s.

By Toomer's time, the state was suffering labor shortages due to thousands of rural Blacks leaving in the Great Migration to the North and Midwest. Planters feared losing their pool of cheap labor. Trying to control their movement, the legislature passed laws to prevent outmigration. It also established high license fees for Northern employers recruiting labor in the state. This was a formative period for Toomer; he started writing about it while still in Georgia and, while living in Hancock County, submitted the long story "Georgia Night" to the socialist magazine The Liberator in New York.

Toomer returned to New York, where he became friends with Waldo Frank. They had an intense friendship through 1923, and Frank served as his mentor and editor on his novel Cane. The two men came to have strong differences.

During Toomer's time as principal of Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute in Georgia, he wrote stories, sketches, and poems drawn from his experience there. These formed the basis for Cane, his High Modernist novel published in 1923. Cane was well received by both Black and white critics. Cane was celebrated by well-known African-American critics and artists, including Claude McKay, Nella Larsen, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Wallace Thurman.

Cane is structured in three parts. The first third of the book is devoted to the Black experience in the Southern farmland. The second part of Cane is more urban and concerned with Northern life. The conclusion of the work is a prose piece entitled "Kabnis." People would call Toomer's Cane a mysterious brand of Southern psychological realism that has been matched only in the best work of William Faulkner. Toomer was the first poet to unite folk culture and the elite culture of the white avant-garde.

The book was reissued in 1969, two years after Toomer's death. Cane has been assessed since the late 20th century as also an "analysis of class and caste", with "secrecy and miscegenation as major themes of the first section". He had conceived it as a short-story cycle, in which he explores the tragic intersection of female sexuality, Black manhood, and industrial modernization in the South. Toomer acknowledged the influence of Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio (1919) as his model, in addition to other influential works of that period. He also appeared to have absorbed The Waste Land of T. S. Eliot and considered him to be one of the American group of writers he wanted to join, "artists and intellectuals who were engaged in renewing American society at its multi-cultural core."

Many scholars have considered Cane to be Toomer's best work. Cane was hailed by critics and has been considered as an important work of both the Harlem Renaissance and Modernism. However, as previously stated, Toomer resisted racial classification and did not want to be marketed as a "Negro" writer. As he wrote to his publisher Horace Liveright, "My racial composition and my position in the world are realities that I alone may determine." Toomer found it more difficult to get published throughout the 1930s, the period of the Great Depression, as did many authors.

In the 1920s, Toomer and Frank were among many Americans who became deeply interested in the work of the spiritual leader George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff, from Russia, who had a lecture tour in the United States in 1924. That year, and in 1926 and 1927, Toomer went to France for periods of study with Gurdjieff, who had settled at Fontainebleau. He was a student of Gurdjieff until the mid-1930s. Much of his writing from this period on was related to his spiritual quest and featured allegories. He no longer explored African-American characters. Some scholars have attributed Toomer's artistic silence to his ambivalence about his identity in a culture insistent on forcing binary racial distinctions. Wallace Thurman, Dorothy Peterson, Aaron Douglas, and Nella Larsen, along with Zora Neale Hurston and George Schuyler, were among those known to have been Toomer's students in the Gurdjieff work during this period.

Toomer continued with his spiritual exploration by traveling to India in 1939. Later he studied the psychology developed by Carl Jung, the mystic Edgar Cayce, and the Church of Scientology, but reverted to Gurdjieff's philosophy.

Toomer wrote a small amount of fiction in this later period. Mostly he published essays in Quaker publications during these years. He devoted most of his time to serving on Quaker committees for community service and working with high school students.

His last literary work published during his lifetime was Blue Meridian, a long poem extolling, "the potential of the American race". He stopped writing for publication after 1950. He continued to write privately, however, including several autobiographies and a poetry volume titled, The Wayward and the Seeking. He died in 1967 after several years of poor health.