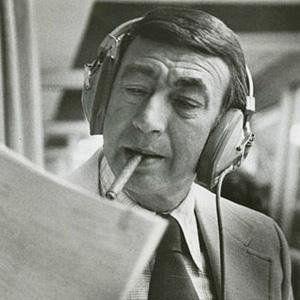

Howard Cosell

Howard Cosell was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States on March 25th, 1918 and is the Sportscaster. At the age of 77, Howard Cosell biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 77 years old, Howard Cosell has this physical status:

In the early 1950s, Cosell had a sports radio show which he would record early in the morning. Ned Garver recalled doing an interview with him in 1951. Cosell told Garver that the sponsor did not provide any gifts to the guests on the show, but Garver found out later that there were actually gifts, which Cosell kept for himself.

Cosell represented the Little League of New York, when in 1953, Hal Neal (president ABC Radio), then an ABC Radio manager, asked him to host a show on New York flagship WABC featuring Little League participants. The show marked the beginning of a relationship with WABC and ABC Radio that would last his entire broadcasting career.

Cosell hosted the Little League show for three years without pay, and then decided to leave the law to become a full-time broadcaster. He approached Robert Pauley, President of ABC Radio, with a proposal for a weekly show. Pauley told him the network could not afford to develop untried talent, but he would be put on the air if he would get a sponsor. To Pauley's surprise, Cosell came back with a relative's shirt company as a sponsor, and "Speaking of Sports" was born.

Cosell took his "tell it like it is" approach when he teamed with the ex–Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher "Big Numba Thirteen" Ralph Branca on WABC's pre- and post-game radio shows of the New York Mets in their nascent years beginning in 1962. He pulled no punches in taking members of the hapless expansion team to task.

Otherwise on radio, Cosell did his show, Speaking of Sports, as well as sports reports and updates for affiliated radio stations around the country; he continued his radio duties even after he became prominent on television. Cosell then became a sports anchor at WABC-TV in New York, where he served in that role from 1961 to 1974. He expanded his commentary beyond sports to a radio show entitled Speaking of Everything.

Cosell rose to prominence in the early-1960s, covering boxer Muhammad Ali, beginning from the time he fought under his birth name, Cassius Clay. The two seemed to have an affinity despite their different personalities, and complemented each other in broadcasts. Cosell was one of the first sportscasters to refer to the boxer as Muhammad Ali after he changed his name, and supported him when he refused to be inducted into the military. Cosell was also an outspoken supporter of Olympic sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith, after they raised their fists in a "black power" salute during their 1968 medal ceremony in Mexico City. In a time when many sports broadcasters avoided touching social, racial, or other controversial issues, and kept a certain level of collegiality towards the sports figures they commented on, Cosell did not, and indeed built a reputation around his catchphrase, "I'm just telling it like it is."

Cosell's style of reporting transformed sports broadcasting in the United States. Whereas previous sportscasters had mostly been known for color commentary and lively play-by-play, Cosell had an intellectual approach. His use of analysis and context brought television sports reporting closer to "hard" news reporting. However, his distinctive staccato voice, accent, syntax, and cadence were a form of color commentary all their own.

Cosell earned his greatest interest from the public when he backed Ali after the boxer's championship title was stripped from him for refusing military service during the Vietnam War. Cosell found vindication several years later when he was able to inform Ali that the United States Supreme Court had unanimously ruled in favor of Ali in Clay v. United States.

Cosell called most of Ali's fights immediately before and after the boxer returned from his three-year exile in October 1970. Those fights were broadcast on tape delay usually a week after they were transmitted on closed circuit. However, Cosell did not call two of Ali's biggest fights, the Rumble in the Jungle in October 1974 and the first Ali–Joe Frazier bout in March 1971. Promoter Jerry Perenchio selected actor Burt Lancaster, who had never provided color commentary for a fight, to work the bout with longtime announcer Don Dunphy and former light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore. Cosell attended that fight as a spectator only. He would do a voice-over of that bout, when it was shown on ABC a few days before the second Ali-Frazier bout in January 1974.

Perhaps his most famous call took place in the fight between Joe Frazier and George Foreman for the World Heavyweight Championship in Kingston, Jamaica in 1973. When Foreman knocked Frazier to the mat the first of six times, roughly two minutes into the first round, Cosell yelled out:

His call of Frazier's first trip to the mat became one of the most quoted phrases in American sports broadcasting history. Foreman beat Frazier by a TKO in the second round to win the World Heavyweight Championship.

Cosell provided blow-by-blow commentary for ABC of some of boxing's biggest matches during the 1970s and the early-1980s, including Ken Norton's upset win over Ali in 1973 and Ali's defeat of Leon Spinks in 1978 recapturing the heavyweight title for the third time. His signature toupee was unceremoniously knocked off in front of live ABC cameras when a scuffle broke out after a broadcast match between Scott LeDoux and Johnny Boudreaux. Cosell quickly retrieved his hairpiece and replaced it. During interviews in studio with Ali, the champion would tease and threaten to remove the hairpiece with Cosell playing along but never allowing it to be touched.

Ali would frequently refer to Cosell's hairpiece as a squirrel, rabbit or other wild animal. On one of these occasions, Ali quipped, "Cosell, you're a phony, and that thing on your head comes from the tail of a pony."

With typical headline generating drama, Cosell abruptly ended his broadcast association with the sport of boxing while providing coverage for ABC for the heavyweight championship bout between Larry Holmes and Randall "Tex" Cobb on November 26, 1982. Halfway through the bout and with Cobb absorbing a beating, Cosell stopped providing anything more than rudimentary comments about round number and the participants punctuated with occasional declarations of disgust during the 15 rounds. He declared shortly after the fight to a national television audience that he had broadcast his last professional boxing match.

Cosell also was an ABC commentator for the television broadcast of the second of the two famous 1973 "Battles of the Sexes" tennis matches, this one between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King.

During Cosell's tenure as a sportscaster, he frequently clashed with longtime New York Daily News sports columnist Dick Young, who rarely missed an opportunity to denigrate the broadcaster in print as an "ass", a "shill", or most often, "Howie the Fraud". Young would sometimes stand near Cosell and shout profanities so that the audio he was taping for his radio show would be unusable. Writing about Cosell, sportswriter Jimmy Cannon sniped, "This is a guy who changed his name, put on a toupee and tried to convince the world that he tells it like it is." He further added, "If Howard Cosell were a sport, he'd be roller derby."

Cosell, according to longtime ABC racecaster Chris Economaki, "had an enormous and monumental ego, and may have been the most pompous man I've ever met". Cosell ripped Economaki for a miscue in an interview with Cale Yarborough for ABC "(and he) never let me forget that". At an ABC Christmas party Economaki's wife asked to be introduced to Cosell and Chris said, "'Howard, for some inexplicable reason my wife wants to meet you...' and it (ticked) him off to no end. He really took it personally."

In 1970, ABC executive producer for sports Roone Arledge hired Cosell to be a commentator for Monday Night Football (MNF), the first time in 15 years that American football was broadcast weekly in prime time. Cosell was accompanied most of the time by ex-football players Frank Gifford and "Dandy" Don Meredith.

Cosell was openly contemptuous of ex-athletes appointed to prominent sportscasting roles solely on account of their playing fame. He regularly clashed on-air with Meredith, whose laid-back style was in sharp contrast to Cosell's more critical approach to the games.

The Cosell-Meredith-Gifford dynamic helped make Monday Night Football a success; it frequently was the number one rated program in the Nielsen ratings. The inimitable style of the group (mostly with Cosell, both loved and hated by the public) distinguished Monday Night Football as a distinct spectacle, and ushered in an era of more colorful broadcasters and 24/7 TV sports coverage.

It was during his MNF run that Cosell coined a phrase that came to be so identified with football that other announcers and spectators—notably Chris Berman—began to repeat it. An ordinary kickoff return began with Cosell giving commentary about a player's difficult life. It became extraordinary when he suddenly observed, in his trademark staccato rhythm, "He could ... go all ... the way!"

Cosell has been credited for popularizing the term "nachos" during his time in the MNF booth.

During the first half of the September 5, 1983 Monday Night Football game between the Dallas Cowboys and Washington Redskins, Cosell's commentary on wide receiver Alvin Garrett included "That little monkey gets loose doesn't he?" Cosell's references to Garrett as a "little monkey," ignited a racial controversy that laid the groundwork for Cosell's departure from MNF at the end of the 1983 season. The Rev. Joseph Lowery, then-president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, denounced Cosell's comment as racist and demanded a public apology. Despite supportive statements by Jesse Jackson, Muhammad Ali, and Alvin Garrett himself, the fallout contributed to Cosell's decision to leave Monday Night Football following the 1983 season.

"I liked Howard Cosell," Garrett said. "I didn't feel that it was a demeaning statement." Cosell explained that Garrett's small stature, and not his race, was the basis for his comment, citing the fact that he had used the term to describe his own grandchildren. Among other evidence to support Cosell's claim is video footage of a 1972 preseason game between the New York Giants and the Kansas City Chiefs that features Cosell referring to athlete Mike Adamle, a 5-foot, 8-inch, 195-pound Caucasian, as a "little monkey."

Along with Monday Night Football, Cosell worked the Olympics for ABC. He played a key role on ABC's coverage of the Palestinian terror group Black September's mass murder of Israeli athletes in Munich at the 1972 Summer Olympics; providing reports directly from the Olympic Village (his image can be seen and voice heard in Steven Spielberg's film about the terror attack).

In the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal, and the 1984 games in Los Angeles, Cosell was the main voice for boxing. Sugar Ray Leonard won the gold medal in his light welterweight class at Montreal, beginning his meteoric rise to a world professional title three years later. Cosell became close to Leonard, during this period, announcing many of his fights.

Cosell was widely attributed with saying the famous phrase "the Bronx is burning". Cosell is credited with saying this during Game 2 of the 1977 World Series, which took place in Yankee Stadium on October 12, 1977. For a couple of years, fires had routinely erupted in the South Bronx, mostly due to owners of low-value properties burning their own real estate for insurance money. During the bottom of the first inning, an ABC aerial camera panned a few blocks from Yankee Stadium to a building on fire. The scene became a defining image of New York City in the 1970s. Cosell supposedly stated, "There it is, ladies and gentlemen. The Bronx is burning." This was later picked up by presidential candidate Ronald Reagan, who then made a special trip to the Bronx, to illustrate the failures of politicians to address the issues in that part of New York City.

In 2005, author Jonathan Mahler published Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bronx Is Burning, a book about New York in 1977, and credited Cosell with the title quote during the aerial coverage of the fire. ESPN produced a 2007 mini-series based on the book The Bronx Is Burning. Cosell's comment seemed to have captured the widespread view that New York City was in a state of decline.

The truth was discovered after Major League Baseball published a complete DVD set of all of the games of the 1977 World Series. Coverage of the fire began with Keith Jackson's comments regarding the enormity of the blaze, while Cosell added that President Jimmy Carter had visited that area just days before. At the top of the second inning, the fire was once again shown from a helicopter-mounted camera, and Cosell commented that the New York Fire Department had a hard job to do in the Bronx as there were always numerous fires. In the bottom of the second, Cosell informed the audience that it was an abandoned building that was burning and no lives were in danger. There was no further comment on the fire, and Cosell appears to have never said "The Bronx is Burning" (at least not on camera) during Game 2.

Mahler's confusion could have arisen from a 1974 documentary entitled The Bronx Is Burning; it is likely Mahler confused the documentary with his recollection of Cosell's comments when writing his book.

On the night of December 8, 1980, during a Monday Night Football game between the Miami Dolphins and the New England Patriots, Cosell shocked the television audience by interrupting his regular commentary duties to deliver a news bulletin on the murder of John Lennon in the midst of a live broadcast. Word had been passed to Cosell and Frank Gifford by Roone Arledge, who was president of ABC's news and sports divisions at the time, near the end of the game.

Cosell was initially apprehensive about announcing Lennon's death. Off the air, Cosell conferred with Gifford and others saying "Fellas, I just don't know, I'd like your opinion. I can't see this game situation allowing for that news flash, can you?" Gifford replied, "Absolutely. I can see it." Gifford later told Cosell, "Don't hang on it. It's a tragic moment and this is going to shake up the whole world."

On air, Gifford prefaced the announcement saying, "And I don't care what's on the line, Howard, you have got to say what we know in the booth." Cosell then replied:

Lennon had been shot four times and had not been pronounced dead on arrival, but the facts of the shooting were not clear at the time of the announcement. Lennon once appeared on Monday Night Football, during the December 9, 1974 telecast of a 23–17 Washington Redskins win over the Los Angeles Rams, and was interviewed for a short breakaway segment by Cosell.

ABC had obtained this scoop as a result of the coincidence of an ABC employee, Alan Weiss, being at the same emergency room where the critically wounded Lennon was brought that night. This unwittingly violated a request to the hospital by Lennon's wife, Yoko Ono, to delay reporting his death until she could tell their son, Sean, herself. Sean, age 5, was not watching television at the time as it was near midnight, and Ono was able to break the news to him. NBC beat ABC to the punch, however, interrupting The Tonight Show just minutes before Cosell's announcement with a "breaking news" segment.

In the fall of 1981, Cosell debuted a serious investigative 30-minute magazine show, ABC SportsBeat on ABC's weekend schedule. He made news and covered topics that were not part of general sports coverage - including the first story about drugs in professional sports (the story of former Minnesota Viking Carl Eller's cocaine use), an in-depth look at how NFL owners negotiated tax breaks and incentives for building new stadiums, and together with Arthur Ashe, an investigation into apartheid and sports. Though ratings were low, Cosell and his staff earned three Emmy Awards for excellence in reporting, and broke new ground in sports journalism. At the time, ABC SportsBeat was the first and only regularly scheduled network program devoted solely to sports journalism.

To produce this pioneering program, Cosell recruited a number of employees from outside the ranks of those that produced games, who he felt might be too invested in the success of the athletes and leagues to look at the hard news. He brought in Michael Marley, then a sportswriter for The Washington Post, Lawrie Mifflin, a writer for The New York Times, and a 20-year old researcher who quickly rose to an associate producer, Alexis Denny. As a sophomore at Yale, Ms. Denny had been a student in a seminar that Cosell taught on the "Business of Big-Time Sports in America", and was selected by the Director of Monday Night Football to join their production crew. She took her junior year off to join Cosell's staff at ABC Headquarters in New York City, and produced many segments, including in 1983 a half-hour special report previewing the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Despite the games being one of ABC's biggest investments, with a record-breaking $225 million rights fee at the time, the 30-minute documentary-style program produced by Denny showed many sides of the questions about the viability of the games themselves—from concerns about traffic, pollution and terrorism, to a look at how the sponsorship deals were structured.

In his 1985 autobiography, Cosell reflected on his highly diverse work, and concluded that the SportsBeat series had been his favorite.