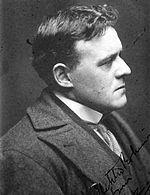

Hilaire Belloc

Hilaire Belloc was born in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, Île-de-France, France on July 27th, 1870 and is the Poet. At the age of 82, Hilaire Belloc biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 82 years old, Hilaire Belloc physical status not available right now. We will update Hilaire Belloc's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (27 July 1870 – 16 July 1953) was an Anglo-French writer and historian and one of the most prolific writers in England during the early twentieth century.

Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist.

His Catholic faith had a strong impact on his works.

He was President of the Oxford Union and later MP for Salford from 1906 to 1910.

He was a noted disputant, with a number of long-running feuds, but also widely regarded as a humane and sympathetic man.

Belloc became a naturalised British subject in 1902 while retaining his French citizenship. His writings encompassed religious poetry and comic verse for children.

His widely sold Cautionary Tales for Children included "Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion" and "Matilda, who told lies and was burnt to death".

He also collaborated with G. K. Chesterton on a number of works.

Family and career

Belloc was born in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, France, to Louis Belloc (1830-1872) and an English mother. Marie Adelaide Belloc Lowndes, his sister, became a writer.

Bessie Rayner Parkes (1829-1955), a writer, activist, and campaigner for women's rights, was a co-founder of the English Woman's Journal and the Langham Place Group, Belloc's mother. Belloc, a member of the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League, protested women's suffrage as an adult.

Joseph Parkes (1796-1865), Belloc's maternal grandfather, was Joseph Parkes (1796-1865). Elizabeth Rayner Priestley (1797–1877), Belloc's grandmother, was born in the United States, and she was a granddaughter of Joseph Priestley.

Bessie Rayner Parkes married Louis Belloc, son of Jean-Hilaire Belloc, in 1867. Louis died in 1872, five years after they wed, but not before being completely devastated by a stock market crash. The young widow brought her children back to England.

Belloc grew up in England; his boyhood was spent in Slindon, Sussex. In poems like "West Sussex Drinking Song," "The South Country," and "Ha'nacker Mill," he wrote about his house. After graduating from John Henry Newman's Oratory School in Edgbaston, Birmingham, Birmingham, Birmingham, Birmingham, Birmingham, England.

Belloc's sister Marie met Mrs. Ellen Hogan, a Catholic widow who was on a European tour in September 1889, with two of her children, Elizabeth and Elodie. Both travellers were devoutly Catholic and keen on literature, and Marie arranged a visit with her mother, Bessie, who in turn arranged visits with Cardinal Henry Manning and Mary Ann Evans, who were best known for her nom de plume of George Eliot. These acts of kindness forged a strong bond, which strengthened when Marie and Bessie accompanied the Hogans on their tour of France, sharing Paris with them. Despite being absent from traveling around France as a reporter for the Pall Mall Gazette, Belloc did not return to London for the first time this year, and was fully enthralled.

Ellen Hogan was called back to California a few weeks later to care for another of her children who was sick with illnesses. Bessie begged her own son to squire the Hogan children around London because she wanted to remain in London under the Belloc family's care. By the day, Belloc's fascination with Elodie had grown more fervid. This was the start of a long, intercontinental, and celebrity-crossed courtship, made all the more difficult by Elodie's mother's plea for Elodie to enter the convent and Hilaire's mother, who believed her son was too young to marry. Belloc pursued Elodie with letters, but he pursued her in person after her return to the United States in 1891.

Belloc, a poor man who is just 20 years old, sold almost every piece of equipment he needed to travel to New York, ostensibly to visit relatives in Philadelphia. After spending a few days in Philadelphia, Belloc's true motivation for the trip to America became apparent right away as he began to travel the African continent. Belloc used to travel by train, but when the money ran out, he walked. Belloc, an endurance man who hiked extensively in the United Kingdom and Europe, rode a stretch of the 2870 miles from Philadelphia to San Francisco on foot. On foot, he paid for lodging at remote farm houses and ranches by sketching the owners and reciting poetry.

Hilaire's first letter upon his arrival in San Francisco is ebullious, eager to see Elodie and full of hopes for their future, but his zealous courtship was to go unrewarded. The joy he felt at seeing Elodie faded quickly as the apparent insurgent resistance of her mother to her marriage revealed itself. The crestfallen Belloc returned to California after a fruitless journey of thousands of miles, but it was much shorter than the time he had spent in his journey to California. Joseph Pearce, his biographer, compared Napoleon's return to Moscow's long winter winter hibery. Belloc's journey to Montclair, New Jersey, on April 30, 1891, he received a letter from Elodie, specifically rejecting him in favour of a religious calling; the steamship ride home was marred with skepticism.

The gloomy Belloc threw himself into restless pursuit. Belloc served his term with an artillery regiment near Toul in 1891, determined to fulfill the obligation of military service while maintaining his French citizenship. When Elodie's mother Ellen died, she was put off by her mother's love for Hilaire and her desire to minister God in the religious life, but Elodie, who was still mourning her mother's death and refused to accept Belloc's advances, was determined to put a halt to Hilaire's aspirations.

He took the entrance exam to Oxford and matriculated to Balliol College, Oxford, after his year of service, still pining for Elodie and still writing her.Belloc would later write in a poem

He was bestowed by his fellow students with a great deal of respect at Oxford: he was elected and served as President of the Oxford Union and served as the University debating society. Anthony Henley, a fellow undergraduate, and another student all made history by walking from Carfax Tower in Oxford to Marble Arch in London, a distance of 55 miles less than double that of a marathon in less than eight hours. In June of 1895, he graduated as a history scholar, obtaining a first-class honours degree.

Elodie, who took the plunge into religious life in the fall, became a member of the Sisters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland, as a postulant. She left Belloc a month later, stating that she had failed in her religious calling. Belloc took a steamship to New York in March 1896 and began traveling to Elodie, California, after obtaining funding as an Oxford Extension lecturer in Philadelphia, Germantown, Baltimore, and New Orleans. He had hoped to be sent letters from her on his travel but he didn't get any. When he finally arrived in California in May, Elodie was acutely ill, exhausting by the previous year's strain, to his surprise and dismay. Belloc's concetion was that after all their pain, he and his family would be denied one another by her death. Elodie recovered over the next few weeks, however, and Hilaire and Elodie were married at St. John the Baptist Catholic church in Napa, California, on June 15, 1896. The happy couple met in Oxford for the first time.

Belloc bought land and a house at Shipley, the United Kingdom, in 1906. The couple had five children before Hogan's death on the Feast of the Purification, most likely from cancer. Belloc, a 45-year-old woman, had more than 40 years of life ahead of him at the time. He wore mourning garb for the remainder of his life, and she preserved her bedroom as she had left it.

Louis was killed in 1918 while serving in the Royal Flying Corps in northern France five years later. Belloc erected a memorial tablet at the nearby Cambrai Cathedral. It is located in the same chapel as Our Lady of Cambray, as the icon.

Belloc's son Peter Gilbert Marie Belloc died of pneumonia at the age of 36 on April 2, 1941. He became sick while in active service with the 5th Battalion, Royal Marines in Scotland. In West Grinstead's Our Lady of Consolation and St. Francis churchyard, he is buried.

Belloc was invited by university president Robert Gannon to teach at Fordham University in New York City in 1937. Belloc gave a series of lectures at Fordham University, which he completed in May of this year. Although excited to accept the invitation, the experience made him physically ill and he considered stopping the lectures early.

Belloc had a stroke in 1941 and never recovered from the effects of the disease. He suffered from burns and shock after falling on his fireplace last year. He died in Guildford, Surrey, on July 16, 1953 at Mount Alvernia Nursing Home.

Belloc was buried at the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Consolation and St Francis in West Grinstead, where he had regularly attended Mass as a parishioner. His estate was valued at £7,451. "No man of his time worked so hard for the noble things" at his funeral Mass, homilist Monsignor Ronald Knox said. Boys from Worth Preparatory School's Choir and Sacristy sang and served at the Mass.

A. N. Wilson and Joseph Pearce's most recent Belloc biographies have been published. Remembering Belloc, a Jesuit political philosopher, was released by St. Augustine Press in September 2013. Henry Edward George Rope wrote Belloc's memoir.

Belloc, the President of the Oxford Union, served at Balliol College. After being a naturalized British subject, he went into politics. His inability to obtain a scholarship at All Souls College, Oxford, in 1895, was a major disappointment in his life. His failure may have been owing in part to the Virgin's small statue of the Virgin and placing it before him at the table during the fellowship interview.

Belloc, a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Salford South, served from 1906 to 1910. He was asked by a heckler if he was a "papist" during one campaign speech. He replied, retrieving his rosary from his pocket.

Despite Belloc's Catholic faith, the crowd booed him and the election was won.

Belloc's only period of stable employment after being in 1914 to 1920 as editor of Land and Water. If he didn't write, he was still struggling financially and was often homeless.

Belloc first came to public attention just after arriving at Balliol College, Oxford, as a new French army soldier. He saw that the affirmative position was wretchedly and half-heartedly defend his first debate of the Oxford Union Debating Society. As the discussion came to an end and the house's split was declared, he rose from his seat in the audience and delivered a spirited, impromptu defense of the plan. Belloc won the audience debate, as the house revealed the house's rift, and his reputation as a debater was established. He was elected president of the Union later this year. In talks with F. E. Smith and John Buchan, the former a friend, he held his own.

Belloc attacked H. G. Wells' book The Outline of History in the 1920s. Belloc criticized Wells' secular bias and his belief in evolution by means of natural selection, a belief that Belloc denied completely. "Debating Mr. Belloc is like arguing with a hail storm," Wells described. Wells' book, according to Belloc's review of Outline of History, was a "up until the appearance of Man," implying somewhere around page seven. Mr. Belloc Objects, a small book by Wells, responded. Belloc did not want to be outdoned, and "Mr. Belloc Objects" was followed by Belloc.

In a 1920 paper, G. G. Coulton wrote Mr. Belloc on Medieval History. Belloc published The Case of Dr. Coulton, a long-running feud, in 1938.

Belloc's style in later life matched the nickname he received in childhood, Old Thunder. In a preface to The Cruise of the Nona, Belloc's companion, Lord Sheffield, outlined his provocative personality.

Belloc will sail when he could afford to do so and became a well-known yachtsman during his later years. He has competed in many events and was on the French sailing team.

He was given a Jersey pilot cutter in the 1930s. He sailed around England for several years, with the help of younger men. Sailing with Mr Belloc, one sailor, wrote a book about it.