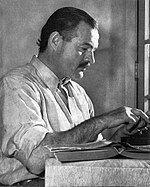

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Illinois, United States on July 21st, 1899 and is the Novelist. At the age of 61, Ernest Hemingway biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 61 years old, Ernest Hemingway has this physical status:

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American journalist, novelist, short-story writer, and sportsman.

His economical and understated style, which he dubbed the iceberg theory, had a major influence on twentieth-century fiction, but later generations, his travel habits and his public face won him adoration.

Hemingway earned the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, and he did the majority of his work between the 1920s and the mid-1950s.

He has written seven books, six short-story collections, and two nonfiction books.

Three of his books, four short-story collections, and three nonfiction books were published posthumously.

Many of his books are considered classics of American literature. Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Illinois.

He served as a journalist for a few months for The Kansas City Star before enlisting as an ambulance driver in World War I. He was seriously wounded in 1918 and returned home.

His wartime experiences influenced his book A Farewell to Arms (1929). Hemingway married Hadley Richardson, the first of four wives, in 1921.

They migrated to Paris, where he served as a foreign correspondent and fell under the influence of the 1920s' "Lost Generation" expatriate group.

In 1926, his debut novel The Sun Also Rises was published.

Richardson divorced Richardson in 1927 and married Pauline Pfeiffer; the pair divorced after he returned from the Spanish Civil War, where he had been a journalist.

He based For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) on his work there.

Martha Gellhorn married Mary Welsh in London in 1940; they divorced after he met Mary Welsh in London during World War II. He was aboard the Normandy landings and the liberation of Paris as a journalist. After the publication of The Old Man and the Sea (1952), Hemingway went on safari to Africa, where he was involved in two near-fatal plane crashes that left him in pain and poor health for the remainder of his life.

He bought a house in Ketchum, Idaho, where he died in mid-1961.

Life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Illinois, an upscale suburb just west of Chicago, to Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a physician, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a singer. His parents lived in Oak Park, a conservative neighborhood in which Frank Lloyd Wright wrote, "There are so many good churches for so many good people to go to." Clarence and Grace Hemingway married in 1896, marrying Ernest Miller Hall, Grace's father, after whom they named their first son, the second of their six children. Marcelline was his uncle before him in 1898, followed by Ursula in 1902, Madelaine in 1911, and Leicester in 1915. Grace followed the Victorian tradition of not categorizing children's clothing by gender. Ernest and Marcelline resembled one-another well into one year of separation between the two countries. Grace wanted them to be twins, so in Ernest's first three years she waited long hair and styled both boys in identical frilly feminine clothing.

Despite her son's inability to learn, Hemingway's mother, a well-known musician in the area, taught him how to play the cello; however, later in life, he admitted that the music lessons contributed to his writing style; as shown by example in the "contraditional system" of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Hemingway confessed to hating his mother, but biographer Michael S. Reynolds points out that he and Hemingway shared similar energies and enthusiasms. Each summer, the family travelled to Windemere, Michigan, near Petoskey, Michigan. Ernest Ernest, a boy from Northern Michigan, joined his dad and learned to hunt, fish, and camp in the woods and lakes of the woods and lakes.

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School in Oak Park from 1913 to 1917. He was a good student, played in a variety of sports, including boxing, track and field, water polo, and football; he and his sister Marcelline, played in the school orchestra for two years; and gained high marks in English classes. During his two years as high school, he edited the Trapeze and Tabula newspaper and yearbook, mimicing sportswriters' language and using the pen name Ring Lardner Jr., a nod to Chicago Tribune byline "Line O'Type." Hemingway, like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis, was a writer before becoming a novelist. After graduating high school, he began working with The Kansas City Star as a cub reporter. Although he only was there for six months, he relied on the Star's style guide as a basis for his writing: "Use short sentences." Use short first paragraphs. Use a lot of English. Be positive, not negative."

Hemingway resigned from New York and arrived in Paris in December 1917, after being rejected by the US Army for bad eyesight, but he continued to be an ambulance driver in Italy. He appeared on the Italian Front in June. On his first day in Milan, he was sent to help rescuers retrieve the shredded remains of female employees's bodies. "I remember that after we searched for the complete dead we found fragments," he wrote in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon. He had been stationed in Fossalta di Piave a few days later.

He was seriously wounded by a mortar fire on July 8, after returning from the canteen, which was selling chocolate and cigarettes for the guys at the front line. Despite his wounds, Hemingway helped Italian soldiers return to health, for which he was honoured with the Italian War Merit Cross, the Croce al Merito di Guerra. At the time, he was only 18 years old. "You have a strong sense of immortality when you go to war as a child," Hemingway said about the incident later. Other people are killed, not you. Then, if you are seriously wounded, is the first time you lose that belief and you know it will happen to you." He suffered severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent immediate surgery at a distribution center, and spent five days in a field hospital before being transferred to a Red Cross hospital in Milan. He spent six months in the hospital, where he met and developed a lasting friendship with "Chick" Dorman-Smith that spanned decades and shared a room with future American foreign service officer, ambassador, and author Henry Serrano Villard.

Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse seven years old, fell in love while recuperating. When Hemingway returned to the United States in January 1919, he was hoping that Agnes would join him within months and the two would marry. Rather, he received a letter in March from her informing that she was engaged to an Italian officer. Agnes' defiance was tragic and frightening, according to biographer Jeffrey Meyers; in future relationships, Hemingway followed a pattern of abandoning a woman before abandoning him.

Hemingway returned home early in 1919 to a time of readjusting. He had gained a maturity from the war, but that was at odds with living at home without a job and with the need for recovery. "Hemingway could not really tell his parents what he thought when he saw his bloody knee," Reynolds explains. He was unable to tell them how afraid he had been "in another world with doctors who couldn't tell him whether his leg was coming off or not" in English."

In September, he joined high-school classmates to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan's back country. The trip inspired his short story "Big Two-Hearted River," in which Nick Adams, a semi-autobiographical character, takes to the country to find solitude after returning from war. A family friend suggested a Toronto job, but he turned down, because he had nothing else to do. He began as a freelancer and staff writer for the Toronto Star Weekly in late this year. He returned to Michigan in June and then migrated to Chicago in September 1920 to live with colleagues, while still writing about the Toronto Star. He spent time in Chicago as an associate editor of the monthly publication Cooperative Commonwealth, where he encountered novelist Sherwood Anderson.

Hemingway, a St. Louis native, became infatuated while visiting the sister of Hemingway's roommate, Hemingway. "I knew she was the one I was going to marry," he later confessed. Hadley, a red-haired boy with a "nurturing instinct," was eight years older than Hemingway. Despite the age gap, Hadley, who had grown up with an overprotective mother, appeared less mature than average for a young woman her age. Hadley was "evocative" of Agnes, according to Bernice Kert, author of The Hemingway Women, but Hadley had a childishness that Agnes lacked, but not Agnes. For a few months, the two couples lived in a few months before deciding to marry and fly to Europe. They had intended to visit Rome but Sherwood Anderson advised them to visit Paris instead, composing letters of introduction for the young couple. They were married on September 3, 1921; two months later Hemingway was hired as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, and the pair moved to Paris. Meyers writes about Hemingway's marriage to Hadley: "Hemingway achieved everything he hoped for with Agnes: the love of a beautiful woman, a secure salary, and a life in Europe."

Although Anderson suggested that Paris be a cheap place to live because "the monetary exchange rate" made it a good place to live, more importantly, it was where "the world's most interesting people" lived. Hemingway met with American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein, Irish novelist James Joyce, American poet Ezra Pound (who "may be able to help a young writer advance to the top of a career"), and other writers in Paris.

"Tall, handsome, muscular, broad-eyed, bloek, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man" in the early Paris years, Hemingway, was a "tall, beautiful, lanky-cheeked, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man." He and Hadley lived in a tiny walk-up at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter, and he worked in a rented room in a nearby building. Stein, the cultural crucible in Paris, was Hemingway's mentor and godmother to his son Jack, whom she introduced to the Montparnasse Quarter's expatriate artists and writers, who Hemingway referred to as the "Lost Generation"; a term she coined with the publication of The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway, a regular at Stein's salon, has worked with influential painters like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Juan Gris. He eventually departed from Stein's fame, and the couple's friendship deteriorated into a decades-long literary feud. Hemingway befriended artist Henry Strater, who painted two portraits of him while living in Paris in 1922.

In 1922, Ezra Pound discovered Hemingway by chance at Sylvia Beach's bookshop Shakespeare and Company. In 1923, the two visited Italy and died on the same street in 1924. They developed a strong friendship, and Pound recognized and nurtured a young talent in Hemingway. Hemingway introduced Hemingway to James Joyce, with whom Hemingway often embarked on "alcoholic binges."

Hemingway wrote 88 articles for the Toronto Star newspaper in his first 20 months in Paris. He covered the Greco-Turkish War, where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna, as well as travel articles such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain" and "Trout Fishing in Spain"; "Then Germany has the best, according to Robert Coveney.

Hemingway was stunned to discover that Hadley had lost a suitcase full of his manuscripts at the Gare de Lyon while traveling to Geneva to visit him in December 1922. The couple returned to Toronto in the fall of 1923, where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923. Hemingway's first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems, was published during their absence. Two of the stories were all that remained after the suitcase's disappearance, and the third had been published in Italy early this year. A second volume, this time without capitals, was released within months. Hemingway had written six vignettes and a dozen stories during his first visit to Spain, where he experienced the excitement of the corrida. He missed Paris, found Toronto boring, and decided to return to the life of a writer rather than live the life of a journalist.

In January 1924, Hemingway, Hadley, and their son (nicknamed Bumby) returned to Paris and moved to a new apartment on the rue Notre Dame des Champs. Hemingway edited Ford Madox Ford's The Transatlantic Review, which published Pound, John Dos Passos, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and Stein's works, as well as some of Hemingway's own early stories such as "Indian Camp." The dust jacket bore Ford comments when In Our Time was published in 1925. "Indian Camp" received a lot of attention; Ford saw it as a significant young writer's debut, and observers in the United States praised Hemingway for reviving the short story genre with his crisp style and use of declarative sentences. Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald six months before, and the pair began a friendship of "admiration and hostility" in the aftermath. Fitzgerald had published The Great Gatsby the same year as he discovered it, loved it, and decided that his next work had to be a novel.

Hemingway, with his wife Hadley, first attended the Festival of San Fermn in Pamplona, Spain, where he became fascinated by bullfighting. And by much older relatives, it is at this time that he began to be referred to as "Papa" at any time. Hadley would later recall that Hemingway had his own nicknames for everyone and that he did things for his friends; she said she liked to be looked up to. She didn't know how the nickname came to be, but it did happen; nevertheless, it stuck. Hemingway's Michigan boyhood friends Bill Smith, Donald Ogden Stewart, Lady Duff Twysden (recently divorced), her companion Pat Guthrie, and Harold Loeb all returned to Pamplona in 1924 and a third time in June 1925; Hemingway's Michigan boyhood friend Bill Smith, Hemingway's grandfather, Donald Ogden Stewart, Hemingway's grandmother, Harold Loeb; Heming Just days after the fiesta ended, he began writing the draft of what would become The Sun Also Rises, which would take place eight weeks later. A few months later, the Hemingways were forced to spend the winter in Schruns, Austria, where Hemingway began revising the manuscript extensively. Pauline Pfeiffer joined them in January and, against Hadley's advice, they urged Hemingway to sign a Scribner's contract. He left Austria for a short visit to New York to speak with the publishers, and on his return to Paris, he began an affair with Pfeiffer before returning to Schruns to finish the revisions in March. The manuscript arrived in New York in April; he revised the last proof in Paris in August 1926; Scribner's published the book in October.

The Sun also Rises epitomized the postwar expatriate generation, has received good reviews, and is "recognized as Hemingway's best work." Hemingway himself wrote to his editor Max Perkins later that the "point of the book" was not about a decade's demise, but that "the earth abides forever"; the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been "battered" but that they were not lost;

Hemingway's marriage to Hadley deteriorated while he was on The Sun Also Rises. Hadley became aware of his affair with Pfeiffer in early 1926, and the two families returned to Pamplona in July. Hadley's parents requested a divorce on their return to Paris, but she officially requested a divorce in November. They separated their possessions, but Hadley accepted Hemingway's donation of the proceeds from The Sun Also Rises. The couple were divorced in January 1927, and Hemingway married Pfeiffer in May.

Pfeiffer, a wealthy Catholic Arkansas family, had migrated to Paris to work for Vogue magazine. Hemingway converted to Catholicism before his marriage. They honeymooned in Le Grau-du-Roi, where he contracted anthrax and planned his next collection of short stories, Men Without Women, which was released in October 1927 and included his boxing tale "Fifty Grand." "Fifty Grand" was one of the finest short stories to ever read, according to Cosmopolitan magazine editor Ray Long, "the greatest piece of realism" ever read.

Pauline, a pregnant woman, wanted to return to America at the end of the year. They left Paris in March 1928, and John Dos Passos suggested Key West. Hemingway sustained a serious head injury in his Paris bathroom when he pulled a skylight down on his head, thinking he was pulling on a toilet chain. This left him with a prominent forehead scar, which he carried for the remainder of his life. When Hemingway was asked about the scare, he was reluctant to answer. "Never again lived in a large city" after Hemingway's demise from Paris.

Hemingway and Pauline travelled to Kansas City, where their son Patrick Patrick was born on June 28, 1928. Pauline had a difficult job; Hemingway based a version of the event on A Farewell to Arms. Pauline and Hemingway travelled to Wyoming, Massachusetts, and New York after Patrick's birth. In the winter, he was in New York with Bumby, about to board a train to Florida, when he received a cable telling him that his father had killed himself. Hemingway was devastated after his father had written to him earlier and told him not to be concerned about financial difficulties; the letter arrived minutes after the suicide was posted. Hadley must have felt after her own father's death in 1903, and he wrote, "I'll probably go the same way."

Hemingway started working on the A Farewell to Arms draft on his return to Key West in December before heading to France in January. He had finished it in August but decided against it in December, but postponed it. Hemingway's Magazine had been scheduled to start in May but Hemingway was still writing on the end, which he may have rewritten as many as seventeen times. On September 27, the complete novel was published. According to biographer James Mellow, A Farewell to Arms established Hemingway's fame as a leading American writer and displayed a degree of ambiguity that was not present in The Sun Also Rises. (Laurence Stallings, a war veteran, whose story was turned into a drama starring Gary Cooper, was turned into a play). Hemingway, a Spanish writer, wrote his next book, Death in the Afternoon, in mid-1929. Because bullfighting was "of utmost importance, being literally of life and death," he wanted to write a comprehensive study on bullfighting.

Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found "the most picturesque country he had ever seen in the United States West" and hunted deer, elk, and grizzly bears. He was welcomed by Dos Passos in November 1930 and discovered Hemingway broke his arm when carrying Dos Passos to the train station in Billings, Montana, in November 1930. The surgeon tended to the compound's spiral fracture and tied the bone with kangaroo tendons. Hemingway was hospitalized for seven weeks with Pauline tending to him; his writing hand's nerves took as long as a year to recover, during which time he suffered from severe pain during this time.

Gloria Hemingway, his third child, was born in Kansas City on November 12, 1931, as "Gregory Hancock Hemingway." The couple's uncle, Pauline's uncle, bought a house in Key West with a carriage house, but the second floor of which was turned into a writing studio. When Hemingway was in Key West, Hemingway frequented Sloppy Joe's, the local bar. Waldo Peirce, Dos Passos, and Max Perkins were among his friends who joined him on fishing trips and an all-male expedition to the Dry Tortugas. In the meantime, he continued to travel to Europe and Cuba, and although he wrote of Key West in 1933, "We have a fine house here, and the children are all well"—Mellow says he was "clearly restless."

Hemingway and Pauline went on safari to Kenya in 1933. Green Hills of Africa, as well as the short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber", were among the 10-week trips. The two visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya, before heading to Tanganyika, where they hunted in the Serengeti, Lake Manyara, and the west and southeast of today's Tarangire National Park. Their tour guide, Philip Perez, was a well-known "white hunter" who had led Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. Hemingway died on these journeys due to an amoebic dysentery that caused a prolapsed intestine, and he was evacuated by plane to Nairobi, which was an experience recounted in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro." Hemingway returned to Key West in early 1934 to work on the Green Hills of Africa, which he published in 1935 to mixed critiques.

Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, dubbed it the Pilar, and began sailing the Caribbean. He first arrived in Bimini in 1935, where he spent a considerable amount of time. During this time, he wrote To Have and Have Not, which was released in 1937 in Spain, the only book he wrote during the 1930s.

Despite Pauline's reluctance to see him working in a war zone, Hemingway escaped to Spain in 1937 to cover the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). For The Spanish Earth, he and Dos Passos have agreed to work with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens as screenwriters. After José Robles' execution, his companion and Spanish translator, which caused a divide between the two writers, Dos Passos left the project.

Hemingway was welcomed in Spain by journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn, who had met in Key West a year before. Martha was a St. Louis native and, like Pauline, she had worked for Vogue in Paris. "She never catered to him the way other women did," Kert says of Martha. He attended the Second International Writer' Congress in July 1937, the aim of which was to address intellectuals' connection to the war, was held in Valencia, Barcelona, and Madrid, and Pablo Neruda attended by many writers, including André Malraux, Stephen Spender, and Pablo Neruda. Hemingway wrote his only play, The Fifth Column, when the city was being bombarded by Francoist forces late in 1937, while Martha Hemingway was in Madrid with Martha. He returned to Key West for a few months, then back to Spain twice in 1938, where he was among the few British and American journalists not to leave the war when they crossed the river.

Hemingway went from Cuba in his boat to live in Havana's Hotel Ambos Mundos. This was the beginning of Pauline's slow and painful separation, which began when Hemingway met Martha Gellhorn. Martha and his partner, "Lookout Farm"), a 15-acre (61,000 m2) property 15 miles (24 km) from Havana, were soon joined in Cuba by Martha. After the family was reunited on a trip to Wyoming, Pauline and the children were married in Cheyenne, Wyoming, on November 20, 1940.

Hemingway migrated his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho, just outside the newly built resort of Sun Valley, and his winter home to Cuba. When a Parisian friend allowed his cats to eat from the table, he was disgusted, but he became enamored of cats in Cuba and kept hundreds of them on the farm. His cats' descendants live at his Key West home.

Gellhorn's inspiration, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he began in 1934 and ended in July 1940, inspired him to write his most popular book, For Whom the Bell Tolls. It was first published in October 1940. When working on a manuscript, he was supposed to move around, and he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Wyoming, and the Sun Valley. "Triumphantly re-established Hemingway's literary fame," it became a Book-of-the-Month Club pick, which sold half a million copies in less than a month.

Martha was sent by Collier's magazine in January 1941 to China on assignment. Hemingway went with her, sending in dispatches for the newspaper PM, but in general, he disliked China. According to a 2009 book, he may have been recruited to serve for Soviet intelligence agents under the name "Agent Argo." They returned to Cuba before the US declared war in December, when Castro persuaded the Cuban government to help him refit the Pilar, which he intended to use to ambush German submarines off the coast of Cuba.

Hemingway lived in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. As he arrived in London, he met Time magazine reporter Mary Welsh, with whom he became infatuated. Martha was forced to cross the Atlantic in a ship carrying explosives because Hemingway refused to help her obtain a press pass on a plane, and she landed in London with a concussion from a car accident. She was unimpressed by his brother's plight, accused him of bullying and told him that she was "completely finished" and was "fully finished." Martha was the last time Hemingway saw her in March 1945 while he was planning to return to Cuba, and the couple's divorce was finalized later this year. In the meantime, he had begged Mary Welsh to marry him on their third meeting.

According to Meyers, Hemingway led the troops to the Normandy Landings wearing a large head bandage, but not allowed to go ashore because of his "precious cargo" and not allowed to go ashore. The landing craft arrived within sight of Omaha Beach before being attacked by enemy fire and turning back. Hemingway wrote in Collier's that "the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth waves of [landing troops] lay where they had fallen, seeming to be so many heavily loaded bundles on the flat's pebbly stretch between the sea and first cover." Mellow explains that none of the correspondents were allowed to land on the first day, and Hemingway was returned to the Dorothea Dix.

Hemingway became de facto leader to a tiny group of village militia in Rambouillet outside of Paris late in July. Col. Charles "Buck" Lanham's commandment pushed toward Paris. "Hemingway ran into a lot of difficulty playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance activists," says Paul Fussell, "especially if he does it well." This was actually in breach of the Geneva Convention, and Hemingway was arrested on formal charges; he said he "beat the rap" by saying he only gave advice.

He was on August 25 as a journalist at the liberation of Paris as a journalist; but Hemingway's legend, he was not the first to enter the city nor did he liberate the Ritz. He visited Sylvia Beach and Pablo Picasso with Mary Welsh, who joined him; in a spirit of joy, he forgave Gertrude Stein. He experienced heavy combat in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest later this year. In spite of sickness, he had himself driven to Luxembourg on December 17, 1944, to cover The Battle of the Bulge. Lanham was admitted as soon as he arrived, but the majority of the fighting was over.

Hemingway was named a Bronze Star in 1947 for his brave service during World War II. He was commended for being "under fire in combat zones in order to get a realistic picture of the challenges and triumphs of the front-line soldier and his team's combat organization."

During his stay in Cuba from 1942 to 1945, Hemingway said he was "out of work as a writer." He married Mary, who had an ectopic pregnancy five months later, in 1946. In the years after the war, the Hemingway family suffered with a string of accidents and illnesses; "smashed his knee" and sustained another "deep wound on his forehead; Mary broke first her right ankle and then left in multiple skiing injuries; Patrick was seriously wounded in a 1947 car accident and died; in 1940, William Butler Yeats and James Joyce; in 1941, Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; and then Robert Carter, Hemingway's long-time Scribner's editor and friend, Thomas Joyce. During this time, he suffered from severe headaches, elevated blood pressure, obesity, and finally diabetes, many of which were the result of previous accidents and heavy drinking. Despite this, he began to work on The Garden of Eden in January 1946, eventually ending up to 800 pages by June. He started working on "The Land," "The Sea," and "The Air," which he wanted to include in one book titled The Sea Book during the war years. However, both schemes failed, and Mellow says Hemingway's inability to continue was "a symptom of his troubles" during those years.

Hemingway and Mary moved to Europe in 1948, spending several months in Venice. Hemingway fell in love with Adriana Ivancich, then 19 years old, while visiting school. The platonic love affair sparked the book Across the River and Into the Trees, which was written in Cuba during a time of strife with Mary and was released in 1950 to scathing reviews. He wrote The Old Man and the Sea in eight weeks, getting to the point of being furious at the critical reception of Across the River and Into the Trees, insisting that it was "the best I can write ever for any of my life." The Old Man and the Sea became a book-of-the-month pick, made Hemingway a worldwide celebrity, and he received the Pulitzer Prize in May 1953, a month before he set off for his second trip to Africa.

Hemingway was nearly killed in two separate plane crashes in January 1954, while in Africa. He arranged a sightseeing flight over the Belgian Congo as a Christmas gift to Mary. The plane was shot from the air and "crash landed in dense forest" as they were on their way to photograph Murchison Falls. Hemingway's head was scratched, while Mary had two broken ribs. Hemingway suffered burns and another concussion, and their next day, attempting to reach medical attention in Entebbe, they boarded a second plane that exploded at take-off, this one heavy enough to cause cerebral fluid leaks. They landed in Entebbe to find reporters covering Hemingway's death. He briefed the journalists and spent the next few weeks recovering and reading his erroneous obituaries. Hemingway joined Patrick and his wife on a planned fishing trip in February despite his injuries, but his illness caused him to be irascible and difficult to get along with. When a bushfire broke out, he was stabbed again, front torso, lips, left hand, and right forearm. Mary's mother, who died in Venice, told friends the full extent of Hemingway's fractures: two cracked discs, a kidney and liver injury, a dislocated shoulder, and a fractured skull. The accidents may have precipitated the physical degeneration that was supposed to follow. Hemingway, who had been "a thinly controlled alcoholic for a good deal of his life," drank more often than normal to ease the pain of his injuries after the plane crashes.

Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature in October 1954. Carl Sandburg, Isak Dinesen, and Bernard Berenson deserved the award, but he cheerfully accepted the prize. Hemingway "wanted the Nobel Prize," Mellow says, but "there must have been a persistent suspicion in Hemingway's mind that his obituary notices had played a role in the academy's decision," months after his plane crash and subsequent international media coverage." Since he was suffering from the African injuries, he decided against flying to Stockholm. Rather, he sent a speech defining the writer's life: he wrote a letter instead.

Hemingway was bedridden from the start of the year to early 1956. He was advised to stop drinking to reduce liver damage, but then disregarded. In October 1956, he returned to Europe and met Basque writer Pio Baroja, who was critically ill and died just weeks later. Hemingway became sick again on the trip and was hospitalized for "high blood pressure, liver disease, and arteriosclerosis."

He was reminded of trunks he had stored in the Ritz Hotel in 1928 and never recovered while staying in Paris in November 1956. Hemingway discovered notebooks and writing from his Paris years on reclaiming and opening the trunks. When he returned to Cuba in early 1957, he began to shape the recovered work into his book A Moveable Feast. He came to a point of intense activity by 1959: he finished A Moveable Feast (dueling to be out the following year); added chapters to The Garden of Eden; and worked on Islands in the Stream. As he concentrated on the finishing touches for A Moveable Feast, the three children were stored in a safe deposit box in Havana. According to author Michael Reynolds, Hemingway fell into depression at a time when he was unable to recover.

As Hemingway, who was still unhappy with life in Hemingway, considered a permanent move to Idaho, the Finca Viga grew crowded with visitors and tourists. He bought a house overlooking the Big Wood River outside Ketchum and left Cuba in 1959, but he later said he was "delighted" with Castro's overthrowrow of Batista, according to The New York Times. He was in Cuba in 1959, between returning from Pamplona and heading west to Idaho, and the following year for his 61st birthday; however, after learning that Castro intend to nationalize property owned by Americans and other foreign nationals, he and Mary decided not to leave. The Hemingways left Cuba for the last time on July 25, 1960, leaving works and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana. The Finca Viga was expropriated by the Cuban government after the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, complete with Hemingway's collection of "four to six thousand books." President Kennedy arranged for Mary Hemingway to fly to Cuba, where she met Fidel Castro and obtained her husband's papers and painting in exchange for donating Finca Viga to Cuba.

Hemingway continued to rework the information that was released as A Moveable Feast in the 1950s. In mid-1959, he travelled to Spain to study a number of bullfighting studies that had been commissioned by Life magazine. The manuscript was only 10,000 words, but it grew out of control. He was unable to write for the first time in his life, so he begged A. E. Hotchner to help him. Hotchner helped him trim the Life piece down to 40,000 words, and Scribner's permission for a full-length book version (The Dangerous Summer) of nearly 130,000 words. Hemingway was "unusually hesitant, disorganized, and disorganized," according to the Hotchner, who was suffering from poor eyesight.

On July 25, 1960, Hemingway and Mary left Cuba for the final time. He opened a tiny office in his New York City apartment and tried to work, but he departed soon after. He then travelled alone to Spain to be photographed for the front cover of Life magazine. A few days later, the news announced that he was seriously ill and on the verge of death, which terrified Mary until she got a cable from him, "Reports false." Enroute Madrid, Madrid. "Love Papa." He was actually sick, and he seemed to be on the brink of a breakdown. Despite having the first installments of The Dangerous Summer published in Life in September 1960 to good feedback, he went to bed for days and slumped into silence. He left Spain for New York in October, where he refused to leave Mary's apartment, presuming that he was being monitored. She rushed him to Idaho, where physician George Saviers met them on the train.

Hemingway was always worried about money and his wellbeing at this time. He was worried about his income and that he would never return to Cuba to retrieve the manuscripts that he had left in a bank vault. He became ill, suspecting that the FBI was diligently tracking his movements in Ketchum. During World War II, the FBI had opened a file on J. Edgar Hoover, who used the Pilar to patrol the waters off Cuba, and he had an agent in Havana to watch him during the 1950s. Mary had Saviers fly Hemingway to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota in November for hypertension therapy, as he told his patient. Hemingway was at the Mayo Clinic as an agent who was later identified in a letter published in January 1961 by the FBI.

To preserve anonymity, Hemingway was checked in under Savier's name. Meyers adds, "an aura of secrecy surrounds Hemingway's hospitalization at the Mayo" but confirms he was treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as many as 15 times in December 1960 and was "released in ruins" in January 1961. At the Mayo, which records ten ECT sessions, Reynolds gained access to Hemingway's files. The doctors in Rochester told Hemingway that the depressive state for which he was being treated may have been triggered by his long-term use of Reserpine and Ritalin. "What is the sense of destroying my head and erasing my memory, which is my wealth, and throwing me out of business?" Hemingway told Hotchner, "what is the fear of destroying my head and throwing my memory out of place, which is my wealth, and throwing me out of place? It was a miracle cure, but the patient was lost."

Hemingway was back in Ketchum in April 1961, three months after being released from the Mayo Clinic, when Mary "discovered Hemingway holding a rifle" in the kitchen one morning. And once the weather cleared Saviers and admitted him to the Sun Valley Hospital, they departed him; then the patient returned to Rochester. During that visit, Hemingway underwent three electroshock treatments. He was released at the end of June and was home in Ketchum on June 30. In the early morning hours of July 2, 1961, two days later, he "quite intentionally" shot himself with his favorite rifle. He had unlocked his gun rack, walked upstairs to the front door foyer, and fired himself with the "double-barreled shotgun" he had used so often that it must have been a friend," according to Abercrombie & Fitch.

Mary was sedated and admitted to the hospital on the next day, returning home the next day and seeing to the funeral and travel arrangements. When Bernice Kert told the world that his death had been accidental, she says it did not appear to her a conscious lie." Mary Conrad confessed to firing herself during a press interview five years later.

The family and friends of Ketchum were invited to the funeral, which was attended by the local Catholic priest, who believed that the death had been accidental. During the funeral, an altar boy fainted at the top of the casket, and Hemingway's brother Leicester said: "It seemed to me Ernest would have approved of it all." He is buried in the Ketchum cemetery.

Hemingway's behavior during his remaining years had been similar to that of his father before he died; his father may have suffered from hereditary hemochromatosis, characterized by the heavy buildup of iron in tissues, contributing to mental and physical deterioration. Hemingway had been diagnosed with hemochromatosis in early 1961, according to medical reports that were made available in 1991. Ursula and his brother Leicester also died. Heavy drinking made Hemingway's life more difficult.

On the base, a memorial to Hemingway is inscribed with an eulogy written by Hemingway many decades ago: a memorial to a friend.