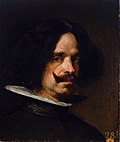

Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez was born in Seville, Andalusia, Spain on June 6th, 1599 and is the Painter. At the age of 61, Diego Velázquez biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 61 years old, Diego Velázquez physical status not available right now. We will update Diego Velázquez's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Diego Rodrón (baptized June 6, 1599 to August 6, 1660) was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in King Philip IV's court and one of the Spanish Golden Age's most important painters.

He was an individualist artist of the Baroque period.

He began to paint in a specific tenebrist style, but then developed a more expressive style characterized by bold foliage.

In addition to numerous interpretations of scenes of historical and cultural importance, he created scores of portraits of the Spanish royal family and commoners, culminating in his masterpiece Las Meninas (1656). Velázquez's artwork became a model for 19th-century realist and impressionist painters.

Since then, well-known modern artists, including Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalh, and Francis Bacon, have paid tribute to Velázquez by reviving several of his most popular works.

Early life

Velázquez was born in Seville, Spain, and Jerónima Velázquez, Juan Rodrs first child. On Sunday, June 6, 1599, he was baptized at the Cathedral of St. Peter in Seville. The baptism most likely occurred a few days or weeks after his birth. Diego da Silva and Mara Rodra Rodra Rodrón, both Portuguese, were relocated to Seville decades ago and are considered Portuguese by his paternal grandparents. Velázquez claimed descent from the lesser nobility in order to qualify in 1658, but his grandparents, possibly Jewish conversos, was in fact.

He was born in modest circumstances and was apprenticed to Francisco Pacheco, an artist and tutor in Seville. Velázquez studied for a brief period under Francisco de Herrera before starting his apprenticeship under Pacheco, but this is undocumented, according to Antonio Palomino, an early-18th-century biographer. Herrera completed a 6-year apprenticeship with Pacheco that dates back to December 1610, and it has been speculated that Herrera may have substituted for a traveling Pacheco between December 1610 and September 1611.

Pacheco was often described as a dull and dissatisfied painter, but his career remained essentially Mannerist. He was highly educated and encouraged his students' intellectual growth as a teacher. Velázquez, a professor at Pacheco's academy, was taught proportion and perspective, and he's followed the Seville literary and artistic fashions.

Juana Pacheco, the daughter of his teacher, was born on April 23, 1618. Velázquez married Juana Pacheco (June 1, 1602 – August 10, 1660). They had two children. On August 21, 1633, the elder, Francisca de Silva Velázquezquez (1619–1658), married painter Juan Bautista Martn del Mazo, 1619–1633, was in Madrid's Church of Santiago. Ignacia de Silva Velázquez y Pacheco, a 1621 girl, died in infancy.

Velázquez's earliest creations are bodegones (kitchen scenes with prominent still life). He was one of the first Spanish artists to paint such scenes, and his Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618) reveals the young artist's remarkable skill in realistic depiction. This work's realisticity and dramatic lighting may have been influenced by Caravaggio's art —which Velázquez may have seen secondhand, in photos — and the polychrome sculpture in Sevillian churches. Two of his bodegones, Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha (1618) and Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (c. 1618), feature religious scenes in the background, allowing confusion as to whether the religious scene is a painting on the wall, a representation of the kitchen maid's thoughts, or a real event seen through a window. The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1618–19) follows Pacheco's formula, but with the face of a local child and varied bushwork, his teacher's idealized facial form and smooth finished surfaces of his teacher are replaced. The Adoration of the Magi (1619) and Saint John the Evangelist on the Isle of Patmos (1618-19) are among his religious works, both of which begin to reflect his more concrete and careful realism.

The portrait of Sor Jerónima de la Fuente (1620) – Velázquez's first full-length portrait – as well as the subject The Water Seller of Seville (1618–1622) is another example from this period. The Water Seller of Seville has been described as "the height of Velázquez's bodegones" and is renowned for its virtuoso rendering of volumes and textures, as well as its enigmatic gravitas.

To Madrid (early period)

By the early 1620s, Velázquez had a name in Seville. He returned to Madrid in April 1622, with letters of introduction to Don Juan de Fonseca, the King's chaplain. Velázquez was not allowed to paint Philip IV, the current king, but rather portrayed Luis de Góngora at Pacheco's request. The portrait depicted Góngora's laurel wreath, which Velázquez later painted over. In January 1623, he returned to Seville, where he stayed until August.

Rodrigo de Villandrando, the king's most popular court painter, died in December 1622. Velázquez was ordered to appear at the courthouse by Gaspar de Guzmán, the powerful minister of Philip IV. He was given 50 ducats (175 g of gold) to defray his expenses, and his father-in-law accompanied him. Fonseca brought the young painter to his house and waited for a portrait, which, when completed, was delivered to the royal palace. The king's portrait was commissioned, and on August 30, 1623, Philip IV sat for Velázquez. The portrait piqued the monarch, and Olivares begged Velázquez to leave Madrid, a promise that no other painter would ever paint Philip's portrait and all other portraits of the king will be banned from circulation. He received 300 ducats from the king in the next year, which became his home for the remainder of his life.

Velázquez gained admission to the royal service at a salary of 20 ducats per month, lodging, and compensation for the photographs he could paint. Philip's portrait was on display on San Felipe's steps and received with a lot of enthusiasm. It is now out of stock (as is Fonseca's portrait). The Museo del Prado, on the other hand, has two of Velázquez' portraits of the king (nos. In this period, the severity of the Seville period has diminished, and the tones are more delicate. 107. 1071). The modeling is solid, recalling Antonio Mor, the Dutch portrait painter of Philip II, who had a large influence on the Spanish academy. The golilla is depicted by Velázquez, who has a stiff linen collar protruding at right angles from the neck. During a period of economic hardship, the golilla reverted to simpler ruffed collars as part of Philip's clothing reform legislation.

In 1623, the Prince of Wales (afterwards Charles I) appeared in the court of Spain. According to accounts, he waited for Velázquez, but the photograph has since been lost.

Philip organized a competition for Spain's best painters in 1627, the object of which was supposed to be the removal of the Moors. Velázquez gained. According to recorded accounts of his painting (destroyed in a fire at the palace in 1734), Philip III pointed with his baton to a crowd of men and women led away by soldiers, while the female personification of Spain remains in sombre repose. Velázquez was named gentleman usher as a token. Later, he was given a daily allowance of 12 réis, the same amount allotted to the court barbers, and 90 ducats a year for dress.

Peter Paul Rubens was stationed in Madrid in September 1628 as an emissary from the Infanta Isabella, and Velázquez led him to visit the Titians at the Escorial. Rubens, who demonstrated his brilliance as a painter and courtier during the seven months of diplomatic service, had a favorable opinion of Velázquez but had no influence on his painting. Velázquez's desire to see Italy and the works of the great Italian masters was not deterred.

Velázquez was awarded 100 ducats for his photograph of Bacchus (The Triumph of Bacchus), also known as Los Borrachos (The Drunks), a portrait of a group of men dressed in modern costume seated on a wine barrel in 1629. Velázquez's first mythological painting has been interpreted in various ways as a recreation of a theatrical performance, as a parody, or as a symbolic representation of peasants begging for refuge from their aches. The style reflects Velázquez's early works, which were barely influenced by Titian and Rubens' influence.

Return to Spain and later career

Philip has been on the lookout for Velázquez's return to Spain as a child from February 1650. Velázquez returned to Spain via Barcelona in 1651, taking with him many photographs and 300 pieces of statuary that were later organized and catalogued for the king.

In 1644, Elisabeth of France had died, but the king had married Mariana of Austria, whom Velázquez now paints in various ways. He was specially chosen by the king to fill the octagon's high office, which meant he would spend the remainder of the court's quarters as a responsible position that was not equal or detrimental to his art. Nonetheless, his output from this period are among the finest examples of his style, rather than implying a decline.

Margaret Theresa, the eldest daughter of the new king's, appears to be the subject of Las Meninas (1656, English: The Maids of Honour), Velázquez's magnum opus. It was created four years before his death and is regarded as one of the best examples of European baroque art. Luca Giordano, a contemporary Italian painter, referred to it as the "theology of painting," and Englishman Thomas Lawrence referred to it as the "philosophy of art" in the eighteenth century. However, it's also unknown as to who or what is the real subject of the photograph. Is it the queen's daughter or the artist himself? The king and queen are seen in a mirror on the back wall, but the source of the reflection is unknown: is the royal pair standing in the viewer's space, or does the mirror reflect the painting on which Velázquez is based? Velázquez may have conceived the faded photograph of the king and queen on the back wall as a precursor to the Spanish Empire's demise, according to Dale Brown.

Les Mots et Les Choses (The Order of Things), a 1966 book by Michel Foucault, devotes the opening chapter to a detailed study of Las Meninas. He explains how the painting debating representation by using mirrors, screens, and subsequent oscillations that occur between the image's interior, surface, and exterior demonstrate.

On the back of the painter's breast, the king is said to have painted the honourary Cross of Saint James of the Order of Santiago. However, Velázquez did not receive this award until three years after its execution of this painting. And the King of Spain could not make his favorite court painter a belted knight without the permission of the commission that had been asked to investigate the lineage of his lineage. The aim of these investigations would be to prevent the recruitment of a taint of Heresy in their lineage, implying a trace of Jewish or Moorish blood or contamination by trade or commerce in either direction of the family for many generations. The Commission's papers were discovered in the Order of Santiago's archives. Velázquez was given the award in 1659. His work as a painter and tradesman was justified because he was clearly not interested in the art of "selling" pictures.

In Spain, there were just two patrons of art: the cathedral and the art-loving king and court. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, a wealthy and powerful church, died without having enough money to pay for his burial, while Velázquez lived and died in the midst of a healthy salary and pension.

Las hilanderas (The Spinners), one of Ovid's last works, was painted circa 1657, a depiction of Ovid's Fable of Arachne. The tapestry in the background is based on Titian's The Rape of Europa, or, more accurately, the copy that Rubens painted in Madrid. It is brimming with light, air, and mobility, with vibrant colors and careful handling. This work seemed to have been created not by the hand, but by sheer force of will, according to Anton Raphael Mengs. The exhibition displays a synthesis of all of the art-knowledge Velázquez obtained during his lengthy artistic career of more than forty years. The scheme is straightforward: a slew of red, bluish-green, gray, and black; a mash-up.

The royal portraits by Velázquez are among his finest works, as well as in the Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress: The painter's personal style reached its high point: shimmering spots of color on broad painting surfaces give the illusion of complete, three-dimensional spatiality.

Prince Felipe Prospero's only living portrait is notable for its blending of the child prince's sweet features with his dog's subtle sense of gloom. The belief that was displayed at the time in the sole heir to the Spanish crown is reflected in the illustration: a new red and white stand in contrast to late fallal, morbid colors. A small dog with wide eyes looks at the viewer as if questioningly, and the largely pale background suggests a gloomy future: the prince was only four years old when he died. The colors used in all of the artist's late paintings are remarkably versatile and vibrant.

Maria Theresa's marriage with Louis XIV in 1660, brought a peace treaty between France and Spain, and the celebration took place on the Island of Pheasants, a small swampy island in the Bidassoa. Velázquez was charged with the decoration of the Spanish pavilion and with the entire scenic display. He attracted a lot of attention because of his nobility of his body and his costume's splendor. He returned to Madrid on June 26 and was stricken with fever on July 31. Feeling his death approaching, he signed his will, naming him as his sole executors his wife and his business colleague, Fuensalida, the royal treasurer. He died on August 6, 1660, according to his biography. He was buried in the Fuensalida vault of San Juan Bautista's cathedral, and within eight days, his wife Juana was buried alongside him. About 1809, this church was demolished by the French, so the site of burial is now unknown.

Adjusting the tangled accounts outstanding between Velázquez and the Treasury was difficult, and it wasn't until 1666, after King Philip's death, that they were finally settled.