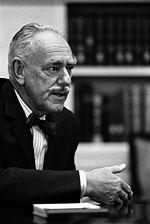

Dean Acheson

Dean Acheson was born in Middletown, Connecticut, United States on April 11th, 1893 and is the Politician. At the age of 78, Dean Acheson biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 78 years old, Dean Acheson physical status not available right now. We will update Dean Acheson's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Dean Gooderham Acheson (pronounced; April 11, 1893 to October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer.

He was a central figure in establishing American foreign policy during the Cold War as US Secretary of State in President Harry S. Truman's administration from 1949 to 1953.

Acheson was a pioneer in the creation of the Truman Doctrine and the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, one of Acheson's most prominent decisions was to convince President Truman to intervene in the Korean War in June 1950.

In 1968, he persuaded Truman to send assistance and consultants to French forces in Indochina, although he eventually advised President Lyndon B. Johnson to negotiate for peace with North Vietnam.

President John F. Kennedy called on Acheson for assistance during the Cuban Missile Crisis, inserting him into the executive committee (ExComm), a strategic consultancy firm. Acheson came under fire for his defense of State Department workers deposed during Senator Joseph McCarthy's and others' investigations into Truman's China policy in the late 1940s.

Early life and education

Dean Gooderham Acheson was born in Middletown, Connecticut, on April 11, 1893. Edward Campion Acheson, an English-born Canadian (immigrated to Canada in 1881) who became a Church of England priest after graduating from Wycliffe College. He immigrated to the United States, eventually becoming Bishop of Connecticut. Eleanor Gertrude (Gooderham), a descendent of William Gooderham, Sr. (1790–1881) and a promoter of Toronto's Gooderham and Words Distillery, was a male descendant of William Gooderham, Sr. (1790-1881). Acheson, like his father, was a stal Democrat and opponent of prohibition.

Acheson attended Groton School and Yale College (1912–1915), where he joined Scroll and Key Society, and was a brother of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Phi chapter). He had the reputation of a partygoer and prankster at Groton and Yale, but his classmates were also popular. Acheson's well-known, well-known arrogance—he disapproved the Yale curriculum because it concentrated on memorizing topics that were not yet known—was apparent early. He was swept away by professor Felix Frankfurter's intellect and placed fifth in his class from 1915 to 1918 at Harvard Law School, but not in 1915.

Personal life

Acheson married Alice Caroline Stanley on May 15, 1917 while serving in the National Guard on May 15, 1917 (August 12, 1895 – January 20, 1996). She loved painting and politics and served as a calming influence during their long marriage; they had three children, David Campion Acheson Brown, Jane Acheson Brown, and Mary Eleanor Acheson Bundy.

Later life and death

On January 20, 1953, the last day of the Truman administration, he and Senator Robert A. Taft, one of his sharpest critics, served on the Yale board of trustees. In 1955, he was named a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Acheson returned to his private law practice. Although his official service was concluded, his name was not established. He was ignored by the Eisenhower administration but he led the Eisenhower administration's Democratic reform groups in the late 1950s. The position papers drafted by this group made up a large part of President John F. Kennedy's flexible response plans.

Acheson's law firms were located a few blocks from the White House and did a good job out of office. He was an unofficial advisor to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. For example, he was sent by Kennedy to France to brief French President Charles de Gaulle and gain his help for the UN blockade. Acheson said he resigned from the executive committee because he so strongly opposed the final decision.

He was a key founder of the Wise Men, a bipartisan group of establishment elders who began to endorse the Vietnam War during the 1960s. Acheson, as secretary of state, had supported the French attempts to influence Indochina as the appropriate price for French assistance of NATO and against communism. However, his view had changed by 1968. President Johnson ordered Acheson to reassess American military strategy, but he concluded that no military victory would be successful. Johnson urged Johnson to get out as soon as possible to prevent a deep split within the Democratic Party from escalating. In terms of de-escalating the conflict and choosing not to run for reelection, Johnson took Acheson's advice and decided not to run for reelection. In 1968, Acheson mistrust Hubert Humphrey and voted for Richard Nixon for president. Through Henry Kissinger, he gave Nixon administration advice, mainly on NATO and African affairs. With the incursion into Cambodia in 1970, he broke with Nixon.

He was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction in 1964. He received the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1970 for his memoirs of his time in the State Department. Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department. The book debuted at #47 on its top 100 non-fiction books of the twentieth century by the Modern Library.

At 6:00 p.m., the New York Times announced that they had a 6:00 p.m. Acheson died of a massive stroke at his farm home in Sandy Spring, Maryland, at the age of 78. In his study, his body was discovered slumped over his desk. In Georgetown, Washington, D.C., Acheson was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery.

He had a son, David C. Acheson (father of Eleanor D. Acheson) and two daughters, Jane Acheson Brown and Mary Acheson Bundy, William Bundy's wife.

Career

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis started a new tradition of brilliant law student clerks for the Supreme Court. From 1919 to 1921, Acheson clerks worked for him for two terms. Both Frankfurter and Brandeis were close friends, and future Supreme Court Justice Frankfurter suggested that Brandeis face Acheson.

Acheson was a natural performer throughout his career: "Acheson demonstrated:

Acheson, a lifelong Democrat, worked at a Washington, Covington, & Burling law firm, often dealing with international legal issues before Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him Undersecretary of the Treasury in March 1933. Acheson unexpectedly found himself acting secretary after Secretary William H. Woodin became sick. He was forced to resign in November 1933 due to his resistance to FDR's attempt to deflate the dollar by manipulating gold prices (thus raising inflation). He revived his court work.

On February 1, 1941, Acheson took over as assistant secretary of state, assisting the United Kingdom and damaging the Axis Powers. Acheson introduced the Lend-Lease program, which helped to re-arm Great Britain and the American/British/Dutch oil embargo, which cut off 95% of Japanese oil supply and exacerbated the crisis with Japan in 1941. Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets merely to surprise them. He did not intend the oil transport to Japan to stop. The president then departed Washington for Newfoundland to speak with Churchill. Although Acheson was gone, he used frozen funds to deny Japan oil. On the president's return, he decided that it would be weak and apprehension to reverse the de facto oil embargo.

Acheson was the head delegate from the State Department at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. The post-war international economic system was conceived at this conference. It was the beginning of the World Bank and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the last of which would evolve into the World Trade Organization.

Harry S. Truman appointed Acheson as the Undersecretary of the United States Department of State in 1945; he kept this post under Secretaries of State Edward Stettinius, Jr., and George Marshall. Acheson attempted to find peace with the Soviet Union as late as 1946. He wrote the Acheson–Lilienthal report in 1946, as chairman of a special commission commissioned to develop a strategy for international control of atomic energy. Acheson had been conciliatory to Joseph Stalin at first.

Acheson's perspective was shaken by the Soviet Union's attempts at regional hegemony in Eastern Europe, Turkey, and Iran. "Acheson was more than 'present at the commencement' of the Cold War,' according to one historian; he was a primary architect." Acheson served as acting secretary on several overseas trips, and during this period, he maintained a close friendship with President Truman. Acheson formulated the scheme and wrote Truman's 1947 request to Congress for assistance to Greece and Turkey, a speech that stressed the dangers of totalitarianism (but did not mention the Soviet Union) and signaled the fundamental change in American foreign policy, which was referred to as the Truman Doctrine.

President Truman awarded Acheson the Medal for Merit on June 30, 1947.

After the unexpected Democratic triumph in the 1948 elections that shocked no one, who lost China during the summer of 1949, it was unclear who lost China. "Acheson requested that the State Department conduct a report on recent Sino-American relations" from the State Department. The paper, which later became known as United States Relations with China, from 1944-1949, was published as the China White Paper, and it denied any misinterpretations of Chinese and American diplomacy toward each other. The 1,054-page paper, which appeared during Mao Zedong's re-election, argued that American involvement in China was doomed to fail. Although Acheson and Truman had hoped that the study would debunk myths and conjecture, many commentators were surprised to learn that the Chinese government had indeed failed to prevent communism from spreading.

Acheson's address on January 12, 1950, long before the National Press Club did not mention the Korea Peninsula and Formosa (Taiwan) as part of the US's all-important "defense perimeter." Since the war in Korea broke out on June 25, just a few months later, analysts, especially in South Korea, expected Acheson's words to imply that the US will not intervene if they invaded the South Koreans. When Soviet archives opened in the 1980s, however, research revealed that the speech had no effect on the Communist decision for war in Korea.

China went from a close friend of the United States to a brutal adversary during the Communist takeover of mainland China in 1949. Critics blamed Acheson for "loss of China" and began many years of organised resistance to Acheson's tenure; Acheson chastised his opponents and wrote "The Attack of the Primitives" during his outspoken memoirs. Despite maintaining his role as a committed anti-communist, a variety of anti-communists were chastised for not playing a more active role in fighting communism abroad and domestically, rather than referring to his communist expansion's containment policy. Both he and Secretary of Defense George Marshall came under fire from men like Joseph McCarthy; Acheson became a byword to some Americans who tried to compare containment with appeasement. Richard Nixon, a congressman who later as president, mocked "Acheson's College of Cowardly Communist Containment." Acheson refused to "turn his back on Alger Hiss" when the former was accused of being a Communist spy and found guilty of persuading him not to disclose that he was not a spy, prompting the outrage.