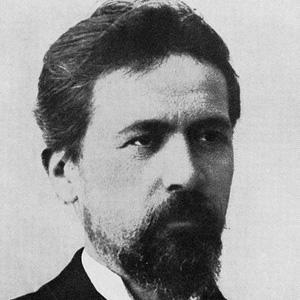

Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov was born in Taganrog, Russia on January 29th, 1860 and is the Playwright. At the age of 44, Anton Chekhov biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 44 years old, Anton Chekhov physical status not available right now. We will update Anton Chekhov's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Antón Pávlovic Céhov, 19 January 1860 – July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short story writer who is considered one of the best writers of short fiction in history.

Writers and commentators alike esteem his playwright's career, and his best short stories are highly regarded.

Chekhov is often referred to as one of the three seminal figures in the early modernism of the theatre, alongside Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg.

Chekhov devoted his time as a medical doctor: "Medicine is my lawful wife," he said once, "and literature is my mistress." "Chekhov renounced the theatre after the 1896 premiere of The Seagull, but Konstantin Stanislavski's Moscow Art Theatre, which then produced Chekhov's Uncle Vanya and premiered his last two plays, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard, revived the performance."

These four works pose a challenge both to the acting ensemble and the audience, since Chekhov's "theatre of mood" and a "submerged life in the text" replaces conventional action, but Chekhov's creation inspired the evolution of the modern short story.

He made no excuses for the reader's nefarious, insisting that the job of an artist was to ask questions rather than answering them.

Early writings

Chekhov took responsibility for the entire family. He wrote daily short, amusing sketches, and vignettes of contemporary Russian life, many under pseudonyms such as "Antosha Chekhonte" and "Man Without Spleen" (нтоек селеенки). His prolific output gradually owed him a reputation as a satirical chronicler of Russian street life, and by 1882, he was writing for Oskolki (Fragments), which was owned by Nikolai Leykin, one of the period's leading publishers. At this stage, Chekhov's tone was harsher than that of his mature fiction.

Chekhov enrolled as a physician, which he regarded as his primary occupation in 1884, although he earned no money from it and treated the homeless homeless free of charge.

Chekhov found himself coughing blood in 1884 and 1885, and the attacks in 1886 escalated, but he would not disclose his tuberculosis to his family or his acquaintances. "I am afraid to be sounded by my coworkers," Leykin said to Leykin. He continued to write for weekly newspapers, and he was able to relocate the family to more comfortable accommodations.

He was encouraged to write for one of St. Petersburg's most popular newspapers, Novoye Vremya (New Times), owned and edited by millionaire financier Alexey Suvorin, who paid a rate per line doubled Leykin's and allowed Chekhov to use three times the space three times the size. Suvorin intended to be a lifelong friend, perhaps Chekhov's closest.

Chekhov had drew literary as well as mainstream notice before long. After reading his short story "The Huntsman," Dmitry Grigorovich, a respected Russian writer of the day, told Chekhov, "You have real talent, a talent that places you in the top ranks among writers of the new generation." He continued to advise Chekhov to relax, write less, and concentrate on literary quality.

"I've written my stories the way journalists write up their fire stories," Chekhov confessed, "I have written my stories the way journalists write up their fire stories, with no concern about either the reader or themselves." Since early manuscripts reveal that he wrote with a great deal of care and was constantly revising, Chekhov may have done him a disservice. Grigorovich's recommendation sparked a more mature, artistic aspiration in the twenty-six-year-old. The short story collection At Dusk (V Sumerkakh), which had a little string-pulling by Grigorovich, received Chekhov's coveted Pushkin Prize "for the best literary achievement distinguished by high artistic value" in 1888.

Chekhov rediscovered Ukraine in 1887, after being exhausted by overwork and poor health, which brought him right back to the steppe's beauty. On his return to work, he began the novella-length short story "The Steppe," which he described as "something rather odd and much too original" and was later published in Severny Vestnik (The Northern Herald). Chekhov creates a chaise journey across the steppe through the eyes of a young boy and his companions, a priest, and a merchant in a story that varies with the characters' thought process. "The Steppe" has been dubbed a "dictionary of Chekhov's poetics," and it represented a major step forward for Chekhov, who appeared in many of his mature fiction and gained him publication in a literary journal rather than a newspaper.

A theatre manager named Korsh ordered Chekhov to write a play in autumn 1887, the result being Ivanov, written in a fortnight and published in November. Despite the fact that Chekhov found the event "sickening" and portrayed a comedic portrayal of the chaotic production in a letter to his brother Alexander, the play was lauded as a work of originality, thanks in large part to Chekhov's bemusement. Even though Chekhov did not fully understand it at the time, his plays, such as The Seagull (written in 1895), Uncle Vanya (written in 1897), and The Cherry Orchard (written in 1903), served as a backbone to what is now known as acting as a modern way to express how people act and communicate with each other. This realistic representation of the human condition may inspire audience discussion of what it means to be human.

This approach to acting has not only been steadfast, but also as the acting's defining feature from the twentieth century to the present day. Ivanov was a pivotal moment in Mikhail Chekhov's intellectual growth and literary career. An example of Chekhov's firearm has surfaced, a dramatic feature that demands that every part of a story be present and irreplaceable, and that everything else be deleted.

Nikolai of Chekhov's tuberculosis in 1889 inspired A Dreary Story, a man who comes to terms with a life in which he realizes he was unprepared. Mikhail Chekhov, who chronicled his brother's depression and hunger after Nikolai's death, as well as Anton Chekhov, who was writing about prisons at the time, and Anton Chekhov, who was looking for a purpose in his own life, became obsessed with prison reform.

Chekhov was transported by rail, horse-drawn carriage, and river steamer to the Russian Far East and the katorga, or penal colony, north of Japan, where he spent three months interviewing thousands of convicts and settlers for a census in 1890. Chekhov's letters on his two-and-a-half journey to Sakhalin are regarded as one of his best. Tomsk's words to his sister were to make him well-known.

Chekhov observed a lot on Sakhalin that shocked and angered him, including flogging, embezzlement of supplies, and forced prostitution of women. "I had times when I felt that I saw the extreme limits of man's decay before me," he wrote. He was particularly moved by the plight of the children who were living in the penal colony with their parents.For example:

Chekhov later found that charity was not the answer, but that the government owed a responsibility to ensure humane care of the prisoners. His papers were published in 1893 and 1894 as Ostrov Sakhalin (The Island of Sakhalin), a social science project rather than literature. Chekhov discovered literary expression for the "Hell of Sakhalin" in his long-short story "The Murder," the last section of which is set on Sakhalin, where the murderer Yakov loads coal in the night while longing for home. In Haruki Murakami's novel 1Q84, Chekhov's essay on Sakhalin, particularly the cultural and habits of the Gilyak people, is the subject of a continuing meditation and analysis. It's also the subject of a poem by Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney, "Chekhov on Sakhalin" (gathered in the volume Station Island). Rebecca Gould compared Chekhov's book on Sakhalin to Katherine Mansfield's Urewera Notebook (1907). The Wellcome Trust-funded play 'A Russian Doctor,' directed by Andrew Dawson and researched by Professor Jonathan Cole, delves into Chekhov's experiences on Sakhalin Island in 2013.

Mikhail Chekhov, a member of Melikhovo's family, detailed the severity of his brother's medical services:

Chekhov's spending on drugs was significant, but the greatest cost was making trips of many hours to visit the sick, which reduced his writing time. However, Chekhov's writing improved his writing by bringing him into close contact with all aspects of Russian society, as he explained in his short story "Peasants." Chekhov visited the upper classes as well as recording in his notebook: "Aristocrats?" The same disgusting bodies and physical uncleanliness, as well as market-women, were the same old age and disgusting death. He served in Zvenigorod, which hosts many sanatoriums and rest homes in 1893-1894. His name has been given to a local hospital.

Chekhov began writing his play The Seagull in 1894 in a lodge he had built in Melikhovo's orchard. In the two years since he had lived on the estate, he had repaired the house, started raising agriculture and horticulture, and planted many trees, some of whom, according to Mikhail, "looked after" as though they were his children. As he looked at them, he wondered what they would be like in three or four centuries years, like Colonel Vershinin in his Three Sisters.

The first night of The Seagull, at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, on October 17th, was a fiasco, with the audience booing Chekhov into renouncing the production. The performance so impressed theatre director Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko that he begged Konstantin Stanislavski to direct a new performance for the Moscow Art Theatre in 1898. Stanislavski's dedication to psychological realism and ensemble casting coaxed the text's buried subtleties and reignited Chekhov's interest in playwriting, as shown by his playwriting. More works by Chekhov were staged, and it was also the staging of Uncle Vanya, which Chekhov had performed in 1896. He became an atheist in the last ten years of his life.

Chekhov suffered a major pulmonary haemorrhage in March 1897 while on a visit to Moscow. With great difficulty, he was refused admission to a clinic where the doctors diagnosed tuberculosis on the upper part of his lungs and ordered a change in his lifestyle.

Chekhov bought a plot of land on the outskirts of Yalta in 1898 and built a house (The White Dacha), which he moved with his mother and sister the following year. Despite growing trees and flowers, kept dogs and tame cranes, and welcomed visitors like Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky, who were often eager to leave his "hot Siberia" for Moscow or relocates abroad. He vowed to move to Taganrog as soon as a water source was established there. He produced two more plays for the Art Theatre in Yalta, composing with greater difficulty than in the days when he "serenibly wrote, the way I eat pancakes now." He spent a year in prison with Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard.

Chekhov married Olga Knipper in a hussiness of weddings on May 25, 1901. She was a former protégée and sometime lover of Nemirovich-Danchenko, whom he first encountered at rehearsals for The Seagull. Up to this point, Chekhov, nicknamed "Russia's most elusive literary bachelor," preferred visiting liaisons and visits to brothels over commitment.He had once written to Suvorin:

Chekhov's marital ties with Olga were unveiled in this letter: she was primarily in Yalta, and she was in Moscow studying her acting career. Olga suffered a miscarriage in 1902; and Donald Rayfield has established that this belief was unfounded, although Russian scholars have denied it. A correspondence that saves theatre treasures, including rumors about Stanislavski's conducting skills and Chekhov's suggestion to Olga about appearing in his performances, is a part of his long-distance marriage.

Chekhov wrote "The Lady with the Dog" (also translated from Russian as "Lady with Lapdog), which describes what appears to be a casual friendship between a cynical married man and an unhappy married woman who met in Yalta while holidaying in Yalta. Neither of them expects anything more from the experience. They eventually fell deeply in love and ended up in danger of their families' lives, which was surprising. The romance depicts their feelings for each other, the inner transformation suffered by the disillusioned male protagonist, and their inability to solve the issue by either letting go of their families or of each other.

Chekhov visited Moscow in May 1903; the influential lawyer Vasily Maklakov visited him almost every day. Maklakov will have signed Chekhov's will. Chekhov was terminally ill with tuberculosis by May 1904. Mikhail Chekhov recalled that "everyone who knew him well thought the time was not far off, but the closer [he] was to the end, the less he seemed to realise it." He and his mother told Badenweiler, Germany's Black Forest, how he wrote outwardly jovial letters to his sister Masha, describing the food and surroundings, and insuring her and his mother that he was getting better. In his last letter, he protested the German women's clothing. Chekhov died on July 15, 1904, at the age of 44, following a long battle with tuberculosis, the same disease that killed his brother.

Chekhov's death has been one of "the great set pieces of literary history" retold, embroidered, and fictionalized many times since, particularly in Raymond Carver's 1987 short story "Errand." Olga's last days in 1908 wrote this story about her husband's last days:

Chekhov's body was moved to Moscow in a refrigerated railway car meant for oysters, which offended Gorky. Thousands of mourners listened to the accompaniment of a military band as a gyne. Chekhov was buried next to his father at the Novodevichy Cemetery.