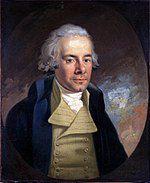

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce was born in Wilberforce House, England, United Kingdom on August 24th, 1759 and is the Politician. At the age of 73, William Wilberforce biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 73 years old, William Wilberforce physical status not available right now. We will update William Wilberforce's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1873), a British politician, philanthropist, and a pioneer of the movement to abolish the slave trade.

He began his political career in 1780, eventually becoming an independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Yorkshire (1784-1812).

He converted to Christianity in 1785, resulting in major changes in his lifestyle and a lifelong desire for reform. He met Thomas Clarkson and a group of anti-slave campaigners, including Granville Sharp, Hannah More, and Charles Middleton in 1787.

Wilberforce was eventually voted out of office for abolition, and he became one of England's top abolitionists.

He led the opposition against the British slave trade for 20 years before the Slave Trade Act of 1807 was passed. Wilberforce was persuaded of the value of faith, morality, and education.

He supported causes and campaigns such as the Society for the Suppression of Vice, British missionary work in India, the establishment of a free colony in Sierra Leone, the foundation of the Church Mission Society, and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

His deep conservatism led him to pass on socially and socioeconomic reforms, resulting in accusations that he was hiding injustices at home while campaigning for the enslaved abroad. Wilberforce, a cadet, voted for complete independence of slavery in later years, and he continued his activism in 1826, when he resigned from Parliament due to his poor health.

The drive resulted in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which abolished slavery in the majority of the British Empire.

Wilberforce died just three days after being told that the Act would be passed through Parliament.

He was buried in Westminster Abbey, near to his buddy William Pitt the Younger.

Early life and education

Wilberforce was born on the 24th of August 1759 in a merchant's house on the High Street of Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. (Wilberforce House is now a historic house museum). He was Robert Wilberforce (1728–1768), a wealthy merchant, and his wife, Elizabeth Bird (1730–1798). William (1690–1774), his grandfather, had made the family fortune in the Baltic maritime trade and sugar refining. He was a partner in a business that constructed the Old Sugar House on Lime Street, which imported raw sugar from plantations in the West Indies. He was twice elected mayor of Hull.

Wilberforce was a small, sickly, and delicate child with poor eyesight. He began attending Hull Grammar School, which at the time was led by Joseph Milner, a young, vivacious headmaster who was to become a lifelong friend. Wilberforce profited from the school's warm and welcoming climate until his father's death in 1768 caused shifts in his living arrangements. With his mother's inability, the nine-year-old Wilberforce was sent to a wealthy uncle and aunt with houses in both St James' Place and Wimbledon, and Wimbledon, at that time. For two years, he attended a "indifferent" boarding school in Putney. He spent his holidays in Wimbledon, England, where he grew fond of his relatives. Because of his relatives' influence, especially that of his aunt Hannah, the wealthy merchant John Thornton's sister, a philanthropist and a promoter of the leading Methodist preacher George Whitefield, he became interested in evangelical Christianity.

The 12-year-old boy was born in 1771 by Wilberforce's staunchly Church of England mother and grandfather, who was angered by these nonconformist influences and his leanings toward evangelicalism. Wilberforce was devastated to be estranged from his aunt and uncle. His family voted against returning to Hull Grammar School because the headmaster had become a Methodist, and Wilberforce continued his education at nearby Pocklington School from 1771 to 1776. He started rejecting Hull's vibrant social life, but as his religious fervour slowed, he took in theatre-going, attended balls, and played cards.

Wilberforce went up to St John's College, Cambridge, in October 1776 at the age of 17. Since his grandfather's death in 1774 and his uncle three years later, he had left him wealthy and as a result, he had no desire or desire to commit themselves to serious study. Instead, he embedded himself in the social cycle of student life and pursued a hedonistic lifestyle, enjoying cards, gaming, and late-night bingeing sessions, though he found some of his fellow students' excesses revolting. Wilberforce was a well-known figure, with wit, generosity, and a good communicator. William Pitt, the more conservative of the two, met many people, including the younger one. Despite his hectic lifestyle and a lack of interest in learning, he passed his examinations and was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1781 and a Master of Arts degree in 1788.

Early parliamentary action

For the first time since the Society for Influencing the Abolition of the Slave Trade, the first meeting of the Society brought together like-minded British Quakers and Anglicans. Rather than advocating for slavery as a natural result of slavery's abolishment, the committee decided to campaign against the slave trade rather than slavery itself. Despite being present informally, Wilberforce did not join the committee officially until 1791.

The society was extremely successful in raising public knowledge and support, and local chapters sprung up across the United Kingdom. Clarkson traveled around the country, collecting first-hand testimony and statistics, while the committee pushed for the campaign, pioneering methods such as lobbying, writing pamphlets, staging press conferences, gaining media attention, organizing protests, and even using a campaign logo: an illustration of a kneeling slave above the motto "Am I not a Man and a Brother?" "This was created by the well-known pottery-maker Josiah Wedgwood. The commission also sought to influence slave-trading nations such as France, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Holland, and the United States, which also worked with anti-slavery activists in other countries and helped with the translation of English-language books and pamphlets. They featured books by former slaves Ottobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano, who had published influential books on slavery and the slave trade in 1787 and 1789 respectively. They and other free blacks, collectively referred to as "Sons of Africa," debated societies and sent spirited letters to newspapers, periodicals, and influential figures, as well as public letters of support for campaign supporters. Hundreds of petitions against the slave trade were submitted in 1788 and the years, with hundreds of thousands of signatories in total. The campaign turned out to be the world's first grassroots human rights movement, in which both men and women from various social classes and backgrounds joined to seek to eliminate the injustices that others had suffered.

During the 1789 parliamentary session, Wilberforce had intended to introduce a motion announcing that he would bring a bill for the abolishment of the Slave Trade. However, he was hospitalized in January 1788 with a likely stress-related illness, which is now known as ulcerative colitis. It was many months before he could return to work, and he spent time convalescing at Bath and Cambridge. His regular bouts of digestive disease led to the use of modestly opium, which was helpful in easing his illness and which he continued to use for the remainder of his life.

Pitt, who had long advocated for abolition, initiated the preparation motion himself and ordered a Privy Council probe into the slave trade in Wilberforce's absence, followed by a House of Commons investigation.

Wilberforce's parliamentary campaign began in April 1789 with the unveiling of the Privy Council's study in April 1789 and the subsequent months of planning. In which he argued that the trade was morally repulsive and a matter of natural justice, he made his first major speech on the subject of abolition in the House of Commons on May 12th. Thomas Clarkson's extensive evidence characterized the appalling conditions in which slaves migrated from Africa in the middle of the nineteenth century, and argued that ending the trade would also bring a change to the living conditions of existing slaves in the West Indies. He proposed 12 resolutions condemning the slave trade, but made no mention of the abolishment of slavery itself, but concentrated on the likelihood of reproduction in the existing slave population if the trade were abolished. With the tide against them, the defenders of abolition postponed the vote by insisting that the House of Commons hear its own evidence, as well as Wilberforce, who has been chastised for prolonging the slave trade. The hearings were not finished by the end of the parliamentary session and were postponed until the following year. In the meantime, Wilberforce and Clarkson continued unsuccessfully to press for France's abolition of the trade, which was, in any case, to be banned in 1794 as a result of the bloody slave rebellion in St. Domingue, but later restored by Napoleon in 1802. Wilberforce succeeded in expediting the hearings by gaining permission for a smaller parliamentary select committee to review the massive amount of evidence that had been accumulated in January 1790. Wilberforce's home in Old Palace Yard became a nexus for the abolitionist movement and a point for several strategic meetings. According to Hannah More, petitioners for other causes thronged him, and his ante-room was thronged from an early hour, like "Noah's Ark, full of beasts, clean and unclean."

The committee was eventually finished receiving witnesses after a general election in June 1790, and Wilberforce introduced the first parliamentary bill to abolish the slave trade in April 1791, following a closely reasoned four-hour address. However, after two evenings of debate, the bill was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88, reflecting a more conservative approach in the aftermath of the French Revolution and a surge in radicalism and slave revolts in the French West Indies. Such was the public hysteria of a time when even Wilberforce himself was accused of being a Jacobin agitator.

Despite rage and hostility, this was the start of a long-running political campaign in which Wilberforce's ostensible commitment never wavered. He was supported in his work by fellow members of the so-called Clapham Sect, one of whom was his closest friend and cousin Henry Thornton. The group, which had evangelical Christian convictions and was later named "the Saints," lived in large houses around Clapham's common, then a village south-west of London. Wilberforce accepted an invitation to share a house with Henry Thornton in 1792, eventually relocating to his own home after Thornton's marriage in 1796. The "Saints" were a small community, characterized by a strong link to practical Christianity and an opposition to slavery. They developed a happier family environment, mingling freely in and out of each other's gardens, and gardens, as well as discussing the numerous religious, socioeconomic, and political topics that interested them.

Enslaved Africans, according to pro-slavery activists, were inferior human beings who profited from their unionship. The Clapham Sect and others were keen to demonstrate that Africans, particularly freed slaves, had human and economic capabilities beyond slavery trade, and that they were capable of sustaining a well-ordered society, trade, and cultivation. They became involved in the establishment of a free colony in Sierra Leone in 1792, inspired in part by Granville Sharp's utopian vision, as well as native Africans and some whites. They founded the Sierra Leone Company, with Wilberforce subscribing generously to the scheme in terms of money and time. The vision was of an ideal society in which races would mix on equal terms; in reality, crop failures, disease, war, and slave defections to the slave trade all heightened. In 1808, the British government assumed responsibility for the colony, which was initially a commercial venture. The colony, though tumultuous at times, was to become a symbol of anti-slavery in which residents, cultures, and African tribal chiefs banded together to prevent slave exchange at the source, which was aided by a British naval blockade to stem the region's slave trade.

Wilberforce introduced a bill calling for abolition on April 2nd, 1792. William Pitt the Younger and Charles Fox, as well as Wilberforce himself, participated in the memorable debate that followed. Over a number of years, Henry Dundas, Home Secretary, suggested a compromise solution of gradual abolition of the Slave Trade. This was defeated by 230 to 85 votes.

Another referendum to abolish the slave trade was barely defeated by eight votes on February 26, 1793. The outbreak of war with France in the same month prevented any further serious consideration of the subject, as politicians remained focused on the national crisis and the threat of invasion. Wilberforce failed to introduce a bill that would ban British ships from selling slaves to foreign colonies in the same year and again in 1794. He expressed his dissatisfaction with the war and urged Pitt and his administration to make further attempts to resolve hostilities. Wilberforce ordered that the government seek a negotiated settlement with France on December 31, 1794, a temporary breach in his long-term friendship with Pitt. Henry Dundas, Pitt's Secretary of State for War, ordered Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with the French colonists of Saint Domingue, which promised to restore the ancien regime, slavery, and discrimination against mixed-race colonists, which attracted criticism from abolitionists Wilberforce and Clarkson.

The French Revolution and British revolutionary parties boosted the loss of public support, leading to a decrease in public support. Clarkson retired in ill-health to the Lake District in 1795, and the Society for Abolition of the Slave Trade's ceased to meet. In 1795, the earliest attempt to bring a bill for abolition of the slave trade was refused in the commons by 78 to 61, and in 1796, although he succeeded in passing the same bill to a third reading, it was later rejected by 74 to 70. Henry Dundas, who secured the 1792 commons "gradual" abolition of slave trade, abstained abolition of slave trade in 1796, who died on January 1, 1796, who voted AYE. As Wilberforce says, enough of his followers must have attended a new comic opera. Despite reduced interest in abolition, Wilberforce continued to introduce abolition bills into the 1790s.

The 19th century's early years in the twentieth century saw a surge in national interest in abolition. Clarkson's career and the Society for Effecting the Slave Trade's Abolition began meeting again in 1804, with new members such as Zachary Macaulay, Henry Brougham, and James Stephen, among other notable new members. Wilberforce's bill to abolish the slave trade passed through the House of Commons in June 1804. However, it was also late in the parliamentary session for it to pass through the House of Lords. It was defeated on reintroduction during the 1805 session, despite the usually sympathetic Pitt's refusal to endorse it. On this occasion and throughout the campaign, abolition was held back by Wilberforce's confidence, also credulous, and his deferential treatment of those in power. He found it difficult to believe that men of rank would not do what he considered to be the right thing, and was reluctant to confront them if they did not.

Wilberforce began to collaborate with the Whigs, particularly the abolitionists, following Pitt's death in January 1806, particularly the abolitionists. In the House of Lords, he gave general support to the Grenville-Fox government, which brought more abolitionists into the cabinet; Wilberforce and Charles Fox led the campaign, while Lord Grenville advocated for the cause.

By maritime lawyer James Stephen, a dramatic change of tactics, which necessitated the introduction of a bill restricting British citizens from aiding or participating in the slave trade to the French colonies, was suggested. Since the bulk of British ships were now flying American flags and slaves to overseas colonies for whom Britain was at war, it was a shrewd move. A bill was introduced and approved by the cabinet, but Wilberforce and other abolitionists opted to avoid referring to the bill's effect. The scheme was fruitful, and the new Foreign Slave Trade Bill was quickly passed and was granted royal assent on May 23, 1806. Wilberforce and Clarkson had amassed a substantial body of evidence against the slave trade over the past two decades, and Wilberforce spent the latter part of 1806 writing A Letter on the Slave Trade, which was a comprehensive restatement of the abolitionist's story. The death of Fox in September 1806 was a tragedy, but a general election was followed shortly in the fall of 1806. Slavery became a political issue, bringing more abolitionist MPs into the House of Commons, including former military men who had lived through the horrors of slavery and slave revolts. Wilberforce was re-elected as an MP for Yorkshire after which he returned to finishing and publishing his Letter, which was in fact, a 400-page book that served as the basis for the campaign's final phase.

Rather than in the House of Lords, Prime Minister Lord Grenville, decided to introduce an Abolition Bill in the House of Lords rather than in the House of Commons, the Prime Minister's first attempt at the Lord Grenville. The bill was passed in the House of Lords by a large margin when a final vote was taken. On February 23, 1807, Sensing a long-awaited change, Charles Grey moved for a second reading in the Commons. The bill was carried by 283 votes to 16. Wilberforce, whose face streamed with tears, was supported by 283 votes to 16. Protesters hoped to abolish slavery itself, but Wilberforce made it clear that total liberation was not the intended aim: "They had to stop the carrying of men in British ships to be sold as slaves." On the 25th of March 1807, the Slave Trade Act received royal approval.

Personal life

William Wilberforce showed no interest in women in his youth, but when he was in his thirties, his friend Thomas Babington recommended Barbara Ann Spooner (1777–1847) as a prospective bride. Wilberforce married her two days later on April 1597 and was immediately smitten; after an eight-day romance, she proposed. Despite the friends' requests to relax, the couple married at the Church of St Swithin in Bath, Somerset, on May 30th 1797. Barbara and Wilberforce were both devoted to each other, and Barbara was extremely attentive and supportive of Wilberforce in his deteriorating illness, despite her lack of concern for his political careers. They had six children in fewer than ten years: William (born 1798), Barbara (born 1801), Elizabeth (born 1802), Robert (born 1802), and Henry (born 1807). Wilberforce, a decadent and adoring father who revelled in his time with his children both at home and at play.

Early parliamentary career

Wilberforce began considering a political career while at university in the winter of 1779–1780, while Pitt and Wilson avidly watched House of Commons debates from the gallery. Pitt, who was still planning on a political career, encouraged Wilberforce to join him in seeking a parliamentary seat. Wilberforce was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Kingston upon Hull in September 1780, at the age of twenty-one and while still a student, and spent over £8,000 to ensure he received the necessary votes. Wilberforce sat as an independent, deciding to be a "no party guy" without any financial pressures. Although chastised for inconsistency, he supported both Tory and Whig governments according to his conscience, served closely with the party in charge, and voted on specific items according to their merits.

Wilberforce went to Parliament regularly, but he also maintained a lively social life, becoming a member of gentlemen's gambling clubs such as Goostree's and Boodle's in Pall Mall, London, which became a part of Goostree's and Boodle's. Madame de Stal, a writer and socialite, referred to him as the "wittiest man in England" and, according to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, the Prince of Wales said he would go somewhere to hear Wilberforce perform.

Wilberforce's speaking out in political speeches was tolerable; the diarist and author James Boswell observed Wilberforce's eloquence in the House of Commons and noted, "I saw what seemed to be a mere shrimp mount on the table; but as I listened, he increased and grew until the shrimp became a whale." Wilberforce's friend Pitt was included in parliamentary debates during the frequent government changes of 1781-1784.

Pitt, Wilberforce, and Edward Eliot (later to become Pitt's brother-in-law) travelled to France for a six-week holiday together in autumn 1783. They visited Paris after a rough start in Rheims, where their presence ignited police suspicion that they were English spies, and they joined the French court at Fontainebleau.

Pitt took power in December 1783, with Wilberforce as a key supporter of his minority government. Despite their close friendship, there is no evidence that Pitt offered Wilberforce a ministerial role in either of the current or future governments. Wilberforce's decision to remain an independent MP may have influenced this decision. On the other hand, Wilberforce's regular lateness and chaos, as well as his persistent vision problems that made reading impossible, may have convinced Pitt that his trusted friend was not ministerial content. Wilberforce never applied for office and was never given one. Wilberforce, a Democrat who was dissolved in the spring of 1784, ran for the county of Yorkshire. On the sixth of April, he was reinstated as an MP for Yorkshire at the age of twenty-four.

Wilberforce began in October 1784 on a tour of Europe that would eventually change his life and determine his future. He traveled with his mother and sister in the company of Isaac Milner, the son of his late former headmaster who had been Fellow of Queens' College, Cambridge, in the year Wilberforce first appeared. They toured the French Riviera and enjoyed the old pastimes of dinners, cards, and gaming. Wilberforce returned to London temporarily in February 1785 to support Pitt's calls for legislative reforms. From where they began their tour to Switzerland, he rejoined the team in Genoa, Italy. Milner accompanied Wilberforce to England, and the pair read The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul by Philip Doddridge, a leading 18th-century English nonconformist.

Wilberforce's faith seems to have started afresh at this moment, despite his earlier involvement in evangelical studies when he was young. He began to rise early to read the Bible and pray, as well as keeping a personal journal. He underwent an evangelical conversion, regretting his youth and deciding to dedicate his future life and work to the service of God. His conversion changed some of his habits, but not his nature: he was outwardly hopeful, curious, and generous, still encourage others to embrace his new faith. He began an agonizing struggle and became progressively self-critical, constantly questioning his faith, time, vanity, self-control, and friendships with others.

Religious indignation was generally viewed as a social regression and was stigmatized in polite society at the time. Evangelicals in the upper classes, including Sir Richard Hill, the Methodist MP for Shropshire, and Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon's, were exposed to contempt and ridicule, and Wilberforce's conversion led him to question whether he should remain in public life. He requested advice from John Newton, the day's most influential evangelical Anglican clergyman and Rector of St Mary Woolnoth in London's City of London. Both Newton and Pitt advised him not to remain in politics, and he did so "with more energy and conscientity." His political convictions were influenced by his faith and his desire to promote Christianity and Christian ethics in private and public life. His convictions were often deeply conservative, opposed to radical changes in a God-given political and economic order, and concentrated on topics such as the Sabbath and the eradication of immorality through education and reform. As a result, he was often mistook him by progressive voices, and some Conservatives who viewed evangelicals as fundamentalists, with some Conservatives viewing evangelicals as radicals.

Wilberforce rented a house in Old Palace Yard, Westminster, in order to be near Parliament in 1786. He began advocating change by introducing a Registration Bill, which contained limited changes to parliamentary election rules. He introduced a bill that extended the statute allowing for the dissection of prisoners after the execution of murders such as rapists, arsonists, and robbers. The bill also recommended the reduction of sentences for women convicted of treason, a felony that at the time also included a husband's murder. Both bills were passed by the House of Commons, but they were defeated in the House of Lords.

In the 16th century, the British became involved in the slave trade for the first time. Around 80% of Great Britain's foreign income by 1783, the triangular route that took British-made products to Africa, transported slaves to the West Indies, and then exported slave-grown sugar, nicotine, and cotton to the United Kingdom. In the harsh conditions of the middle passage, British ships ruled the slave trade, exporting French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonies, and in peak years, forty thousand enslaved men, women, and children across the Atlantic. Approximately 1.4 million Africans were killed during the crossing out of an estimated 11 million Africans enslaved.

The British attempt to ban the slave trade is said to have started in the 1780s with the establishment of the Quakers' anti-slavery committees and the first slave trade petition in 1783, which was presented to Parliament in 1783. Wilberforce was dining with his old Cambridge buddy Gerard Edwards the same year. James Ramsay, a ship's surgeon who had been converted to a priest on the island of St Christopher (later St Kitts) in the Leeward Islands, as well as a medical director of the plantations. Ramsay had been horrified by the slaves' conditions both at sea and in the plantations. After fifteen years in England, he accepted the life of Teston, Kent, and among others Sir Charles Middleton, Lady Middleton, Thomas Clarkson, Hannah More and others, a group that later became the Testonites. Slave owners' stories, along with cruel punishment meted out to the slaves, and a lack of Christian instruction were all appalled by Ramsay's reports of depraved lifestyles, moral development in the United Kingdom and overseas. Ramsay spent three years writing An article on the care and conversion of African slaves in the British sugar colonies, which was highly critical of slavery in the West Indies, thanks to their encouragement and support. The book, which was released in 1784, was to have a major influence on public knowledge and concern, as well as the ire of West Indian planters who, in the coming years, reacted angrily to Ramsay's theories in a series of pro-slavery tracts.

Wilberforce reportedly did not follow up on his Ramsay interview. However, three years later, and inspired by his new faith, Wilberforce's interest in humanitarian reform was on the rise. In November 1786, he was sent a letter by Sir Charles Middleton, re-opening his trade in the slave trade. Sir Charles, at the behest of Lady Middleton, suggested that Wilberforce bring the slave trade to an end in Parliament. Wilberforce said he "felt the importance of the subject and considered himself unethical to the job delegated to him, but would not reject it." He began to read extensively and met with the Testonites at Middleton's home in Teston in the early winter of 1786-1787.

Thomas Clarkson, a fellow undergraduate of St John's, Cambridge, who had been convinced of the need to end the slave trade while writing a prize-winning essay while at Cambridge, called on Wilberforce at Old Palace Yard in early 1787. This was the first time the two guys met; their relationship would last almost 50 years. Clarkson began visiting Wilberforce on a weekly basis, bringing first-hand testimony that he learned about the slave trade. The Quakers, who were still working for abolition, understood the need for authority in Parliament and encouraged Clarkson to request a promise from Wilberforce to bring the case for abolition in the House of Commons.

Bennet Langton, a Lincolnshire landowner and mutual acquaintance of Wilberforce and Clarkson, had planned a dinner party in order to lobby Wilberforce officially to lead the parliamentary campaign, according to it. On March 13, 1787, the dinner was held in the town of Middleton; other guests included Charles Middleton, Sir Joshua Reynolds, William Windham MP, James Boswell, and Isaac Hawkins Browne MP. Wilberforce had decided in general terms that he would bring the slave trade into Parliament before the evening, "provided that no one more suitable could be identified."

On Pitt's estate in Kent, the still uncertain Wilberforce held a chat with William Pitt and future Prime Minister William Grenville on May 12th. Pitt asked his friend, "Wilberforce Oak" at Holwood House: "Why don't you notify me of a motion regarding the Slave Trade?" You've already gone to gather evidence and are therefore perfectly entitled to the credit, which will also guarantee you. Do not delay because otherwise the field will be occupied by another." Wilberforce's reaction is not recorded, but he later announced that he could "definitely recall the knoll on which I was sitting near Pitt and Grenville" where he had made his decision in old age.

Wilberforce's participation in the abolition movement was motivated by a desire to live his Christian values and to serve God in public life. He and other evangelicals were horrified by what they perceived as a depraved and unChristian trade, as well as the owners' and traders' avarice. "God Almighty has laid before me two marvelous things, the suppression of the Slave Trade, and the Reformation of Manners [moral values]," Wilberforce wrote in a journal entry in 1787. The conspicuous participation of evangelicals in the highly popular anti-slavery movement helped to raise the profile of a group traditionally associated with anti-violence and immorality.