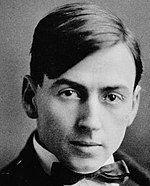

Tom Thomson

Tom Thomson was born in Claremont, Ontario, Canada on August 5th, 1877 and is the Painter. At the age of 39, Tom Thomson biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 39 years old, Tom Thomson physical status not available right now. We will update Tom Thomson's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Thomas John Thomson (August 5, 1877-July 8, 1917) was a Canadian artist active in the early 20th century.

He created approximately 400 oil sketches on small wood panels and more on canvas during his short career.

The majority of his landscapes depict trees, skies, lakes, and rivers.

His paintings portray the Ontario landscape's stunning and vivid colors with broad brush strokes and a liberal use of paint.

Thomson's accidental death at 39 by drowning occurred just weeks before the Group of Seven's founding and is regarded as a tragedy for Canadian art. Thomson, who was born in rural Ontario, was born into a large family of farmers but showed no immediate artistic ability.

He worked in various industries before attending a business college, eventually developing penmanship and copperplate writing skills.

He worked in Seattle and Toronto as a pen artist at several different photoengraving companies, including Grip Ltd. at the start of the twentieth century.

J. E. MacDonald, Lawren Harris, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael, and Arthur Lismer were among the many people who later formed the Group of Seven, including J. E. MacDonald, Lawren Harris, Frederick Varley, Arthur Lismer.

For the first time, he visited Algonquin Park, a major public park and forest reserve in Central Ontario, in May 1912.

He acquired his first sketching kit and began to photograph nature scenes on a budget.

He became enraptured with the area and returned regularly, spending his winters in Toronto and the remainder of the year in the Park.

His early paintings were not particularly impressive technically, but they did a good job of composition and color manipulation.

His later works are more diverse in style, with vibrant colors and thickly applied paint.

His later paintings have a huge influence on Canadian art—paintings like the Jack Pine and The West Wind have occupied a prominent role in Canadian history and are among the country's most popular works. Thomson made a name for himself as a reliable outdoorsman, skilled in both fishing and canoeing, but his canoeing abilities have been questioned.

He drowned on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, bringing his reputation as a master canoeist, resulting in unsubstantiated but persistent rumors that he was killed or committed suicide. Thomson, who died before the group of Seven's formal establishment, is often regarded as an unofficial participant.

His art is often seen in Canada, mainly at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Ottawa, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound.

Life

Thomas John "Tom" Thomson was born in Claremont, Ontario, on August 5, 1877, the sixth of John and Margaret Thomson's ten children. He was born in Leith, Ontario, near Owen Sound in Meaford's municipality. Both drawing and painting were enjoyable, but he did not have any established skills right away. He was eventually kicked out of school for a year due to poor health, including a respiratory condition that was more commonly described as "weak lungs" or "inflammatory rheumatism." He had free time to explore the woods near his house and learn an appreciation of nature.

The family was unsuccessful as farmers; both Thomson and his father frequently abandoned their chores to go hiking, hunting, and fishing. Dr. William Brodie (1831–1909), Thomson's grandmother's first cousin, went on walks in Toronto with his grandmother. Brodie, a well-known entomologist, ornithologist, and botanist, and Thomson's sister Margaret said they collected specimens on long walks together.

Thomson was also enthusiastic about sports, although he was losing his toe while playing football. He was an excellent swimmer and fisherman, passing on his father's obsession with the latter. He went to church on Sunday, like many in his neighborhood. According to several accounts, he sketched in the hymn books during services and entertained his sisters with caricatures of their neighbors. His sisters remarked later that they had fun "guessing who they were," implying that he wasn't necessarily good at capturing people's likeness.

Each of Thomson's nine siblings received an inheritance from their paternal grandfather. Thomson earned $2000 in 1898 but it appears that it was quickly spent. He started a machine shop apprenticeship at an iron foundry owned by William Kennedy, a close friend of his father's, but was fired only eight months later. He registered to fight in the Second Boer War in 1899, but was turned down due to a medical condition. He attempted to enlist for the Boer War three times in all, but was refused each time.

Thomson first attended Chatham, Ontario, in 1901. The school offered training in stenography, bookkeeping, company communications, and "plain and ornamental penmanship." He learned penmanship and copperplate, both of which were necessary for a clerk. He travelled briefly to Winnipeg before heading to Seattle in January 1902, joining his older brother, George Thomson, after graduating at the end of 1901. The Acme Business School in Seattle, founded by George and cousin F. R. McLaren, is the 11th largest business school in the United States. At The Diller Hotel, Thomson worked briefly as an elevator operator. Ralph and Henry, two more of his brothers, had left West to attend the family's new school by 1902.

Thomson was hired by Maring & Laddd as a pen artist, draftsman, and etcher after attending the business school for six months. He made mostly business cards, brochures, and posters, as well as three-color printing. He specialized in lettering, drawing, and painting having previously learned calligraphy. He was known to be stubbornly independent while at Maring & Ladd, and his brother Fraser wrote that, rather than finishing his assignments in the direction suggested, he'd use his own design ideas, which angered his boss. Thomson may have worked as a freelance commercial designer, but there are no current examples of such work.

He later moved to a local engraving business. Despite a good salary, he left before 1904 at a young age. After his brief summer romance with Alice Elinor Lambert, he quickly returned to Leith, possibly owing to a rejected marriage proposal. Lambert, who never married, later became a writer; in one of her stories, she relates a teenage girl who refuses an artist's proposal and regrets later regrets her decision.

Thomson immigrated to Toronto in 1905. On his return to Canada, Legg Brothers, a photo engraving company, earned $11 a week. He spent his free time reading poetry and attending concerts, the theatre, and sporting events. "I love poetry best," he wrote in a letter to an aunt. During this period, friends characterized him as "periodically erratic and sensitive, with occasional bouts of excessive anxiety." He invested his money on luxury clothes, fine dining, and cigarettes, rather than buying art supplies. He may have briefly worked with William Cruikshank, a British artist who taught at the Ontario College of Art, at this time. Cruikshank was possibly Thomson's first formal art instructor.

Thomson joined Grip Ltd., a Toronto firm that specialized in typography and lettering. Grip was the country's top graphic design firm, and it brought Art Nouveau, metal engraving, and the four-color process to Canada. Albert Robson, now the art director of Grip, recalled that Thomson's early work at the company was mostly focused on lettering and decorative designs for booklets and labels. Thomson met new people slowly but later discovered common interests to his coworkers, according to him. Several of the Grip workers were members of the Toronto Art Students' League, a group of newspaper writers, illustrators, and commercial artists active between 1886 and 1904. The members sketched in parts of eastern Canada and released an annual calendar with illustrations depicting Canadian history and rural life.

To improve their skills, J. E. MacDonald, the senior artist at Grip, J. H. MacDonald, urged his workers to paint outside in their spare time. Many of the Group of Seven's potential members met in Grip. Artist William Smithson Broadhead was hired in December 1910 and joined by Arthur Lismer in February 1911. Frederick Varley was eventually hired by Robson, who then became Franklin Carmichael in April 1911. Despite Thomson was not a member of the Arts and Letters Club, MacDonald introduced Thomson to Lawren Harris at the Arts and Letters Club. The club was described as the "center of living culture in Toronto," providing an informal space for the artistic community. Any member of the original Group of Seven had now met. Since the Ontario government bought his canvas By the River (1911), MacDonald left Grip in November 1911 to do freelance work and spend more time painting.

Oliver Mowat and the Ontario Legislature established Algonquin Park in 1893. The Park was established in Central Ontario to provide a space dedicated to recreation, wildlife, and watershed protection, although log operations were still allowed. Thomson learned of the park from fellow artist Tom McLean. He first visited the Park in May 1912, aged 34, and he was raving through the area with his Grip colleague H. B. (Ben) Jackson – My Name Is Alive. They travelled from Toronto to Scotia Junction, then on to the Ottawa, Arnprior, and Parry Sound Railway, eventually arriving at Canoe Lake Station together. G. W. Barlett, McLean, introduced Thomson to the Park superintendent. When they camped nearby on Smoke Lake, Thomson and Jackson met ranger Harry (Bud) Callighen.

Thomson also acquired his first sketching equipment at this time. He didn't even take painting seriously. Thomson did not believe "his work would ever be taken seriously," according to Jackson; in fact, he used to chuckle over the prospect. Rather, the majority of their time was spent fishing, with "a few notes, skylines, and color effects."

Thomson read Izaak Walton's 1653 fishing book The Compleat Angler on the same trip. Primarily a fisherman's bible, the book included a roadmap of life in the woods, similar to Henry David Thoreau's 1854 book Walden, or Life in the Woods, a reflection on simple living in natural surroundings. Walton's "contemplative" life gave him an excellent opportunity to imitate Walton's "contemplative" life in Algonquin Park.Ben Jackson wrote:

Jackson published an article about him and Thomson's stay in the Park in the Toronto Sunday World, which included many illustrations. Thomson and another colleague, William Broadhead, embarked on a two-month journey, scaling the Spanish River and into the Mississagi Forest Reserve (today Mississagi Provincial Park). Around this time, Thomson's evolution from commercial art to his own unique style of painting became apparent. During two canoe spills, a lot of his artwork, mainly oil sketches and photographs, was lost; the first was on Green Lake in a rain squall and the second in a series of rapids.

Albert Robson, Grip's art director, joined Rous & Mann in fall 1912. Thomson followed Robson and left Grip to join Rous & Mann a month after returning to Toronto. Varley, Carmichael, and Lismer followed them soon. Robson praised Thomson's loyalty later in life, describing him as "the most diligent, trustworthy, and skilled craftsman" in the interview. Robson's success in recruiting top talent was well understood. Leonard Rossell said that the artist was involved with them personally and that they did everything he could to advance their development." Many who worked there were given time off to pursue their studies... Tom Thomson, who took no explicit lessons from anyone, yet he advanced faster than any of us. However, what he did was probably of greater benefit to him. In the summer, he took several months off and spent them in Algonquin Park."

MacDonald introduced Thomson to Dr. James MacCallum in October. MacCallum, a frequent visitor to the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) exhibitions, was admitted to the Arts and Letters Club in January 1912. He met artists such as John William Beatty, Arthur Heming, MacDonald, and Harris there. Thomson was eventually convinced by MacCallum to abandon Rous and Mann and begin a painting career. MacCallum introduced Thomson to A. Y. Jackson in October 1913, later a founder of the Group of Seven. Thomson and Jackson's talents were acknowledged by MacCallum, who promised to fund their costs for a year if they committed to painting full time. Both MacCallum and Jackson encouraged Thomson to "take up painting seriously; [but] he showed no enthusiasm. He did not appear promising that a career in it would be profitable. He was both sensitive and independent, and feared he'd be turned into a target of patronage." "I believe they had gripped Thomson as it had gripped me since I was eleven years old when I first sailed and paddled through its remote northland," MacCallum wrote when he first saw Thomson's drawings. Thomson's paintings were described as "dark, muddy in color, tight, and lacking in technical defects," Thomson's words were described. MacCallum was a servant and apologist for Thomson's work after his death.

Thomson accepted MacCallum's bid under the same terms as Jackson. He and his colleagues travelled around Ontario, especially to the wilderness of Ontario, which was to be a major source of inspiration. In a letter to MacCallum regarding Algonquin Park, he wrote: "The best I can do does not do the place much justice in terms of beauty." He ventured to rural areas near Toronto to capture the surrounding area. On the Mattagami reserve, he may have served as a fire ranger. He accompanied fishing tours, according to Addison and Little, although Hill finds this unlikely since Thomson had only spent a few weeks in the Park the previous year. Thomson painted them both with logging scenes as well as nature in the Park.

Thomson stopped in Huntsville while returning to Toronto in November 1912. On Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, a woman whose family owned a cottage was scheduled to speak with Winifred Trainor, a woman whose family owned a cottage. The trainor was later reported to have been engaged to Thomson for a wedding scheduled for the late 1917, but no information was given regarding their relationship.

Thomson first appeared with the OSA in March 1913, delivering his painting Northern Lake (1912–13) to the Ontario Government for $250 (equivalent to CAD$5,900 in 2021). Throughout 1913's summer and fall, he had time to paint and sketch.

Thomson had a tendency to experience self-doubt on a daily basis. A. Y. Jackson recalled that Thomson threw his sketch box into the woods out of envy in 1914, and that he was "too timid to show his sketches." Harris shared similar views, claiming that Thomson "had no opinion of his own work" and would even throw firet matches at his paintings. Several of the canvases he sent to exhibitions remained unsigned. If someone praised one of his sketches, he gave it to them as a gift. In 1914, the National Gallery of Canada, under the direction of Eric Brown, began to collect his works. Although the funds were insufficient to sustain a life, the recognition for an unidentified artist was unprecedented.

He shared a studio and living quarters with fellow artists during his time in the Studio Building with Jackson in January 1914. "The Studio Building is a lively hub for new ideas, experiments, debates, predictions about the future, and visions of an art inspired by the Canadian countryside," Jackson described it. Thomson, "after much self-precation, eventually committed to becoming a full-time artist," he wrote. While the majority of the building was complete, they split the rent—$22 a month—on the ground floor. Carmichael took his place after Jackson moved out in December to go to Montreal. A studio space was shared by Thomson and Carmichael during the winter. Thomson was nominated as a member of the OSA by Lismer and T. G. Greene on March 3, 1914. He was first elected on November 17th. He was not interested in any of their activities other than merely sending paintings for annual exhibitions. Harris recalled Thomson's strange working hours many years ago:

Thomson arrived in Algonquin Park in late April 1914, where he was welcomed by Lismer on May 9. They camped on Molly's Island in Smoke Lake, heading to Canoe, Smoke, Ragged, Crown, and Wolf Lakes. He spent his spring and summer in Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park, visiting James MacCallum by canoe. With such a large area of ground covered in such a short period of time, painting the French River, Byng Inlet, Parry Sound, and Go-Home Bay from May 24 to August 10 has been difficult to determine during this period. Thomson and Lismer left Algonquin Park on May 24, according to H. A. Callighen, a park ranger. Thomson was at Parry Sound by May 30, and MacCallum and MacCallum were camped at the French River on June 1st.

Thomson was in Go-Home Bay for the next two months, or at least until August 10, according to art historian Joan Murray, when he was seen by Callighan in Algonquin Park. According to Wadland, if this timeline is accurate, it would require "an extraordinary canoeist." The challenge is heightened by the fact that you can only sketch at intervals along the way." Thomson may have traveled by rail at some time and then steamship followed, according to Wadland. Instead, Addison and Harwood said Thomson had discovered much of the inland "monotonically flat" and the rapids, which were "normal." Wadland found this description unhelpful, pointing out that Thomson's rapids were not even "normal."

Two of Thomson's paintings, which were published on May 30 and June 1, respectively, were published; MacCallum provided concrete dates for two of Thomson's paintings: May 30 and June 1 for Parry Sound Harbour and Spring, French River. These are some of the few instances of concrete dating for his jobs. A rendering of MacCallum's cottage contrasted with the vast expanse of sky and water on a Rocky Shore. Evening, Pine Island is located on a nearby island, MacCallum brought Thomson Thomson to visit. He painted around the islands until he departed, presumably because MacCallum's cottage was too demanding socially, telling Varley that it was "too much like north Rosedale."

Thomson continued canoeing alone until he met A. Y. Jackson at Canoe Lake in mid-September. Despite World War II having ended last year, Jack and Margaret went on a canoe trip in October, as well as Varley and his wife Maud, as well as Lismer and his wife Esther, and daughter Marjorie. This was the first time three Group of Seven members painted together, and it was the first time they worked with Thomson. A. Y. Jackson's book A Painter's Country in 1958, A. A. Jackson said, "had it not been for the war, the group [of Seven] would have existed several years before, and it would have included Thomson."

It has been discussed why Thomson did not deploy in the war. Several attempts to enlist, likely due to his inability and age, but also likely because he had flat feet, according to Mark Robinson and Thomson's family. Thomson's artist friends tried to persuade him not to risk his life, but they decided to secretly volunteer anyway. Andrew Hunter has found this situation to be improbable, particularly because other artist friends served for the war, including A. Y. Jackson. Thomson's sister said that he was a pacifist and that "he disliked war" and that he "would never kill anyone" but that if accepted, he'd like to work in a hospital." Thomson "brooded a lot" during the war, according to William Colgate, and that "he himself did not enlist." According to rumors, he attempted to pass the doctor but failed to do so. This is doubtful. "We had several discussions on the war," Edward Godin, a companion. As I recall it, he did not believe that Canada should be concerned. He was outspoken in his opposition to government patronage. Particularly in the Militia. I don't think he'd be offering himself for hire. I know he hadn't tried to enlist until that time. There is only one verifiable example of Thomson's view on the war derived from a letter he wrote to J. E. MacDonald in 1915: he wrote to J. E. MacDonald in 1915.

Thomson's financial outlook became uncertain as a result of MacCallum's year of financial assistance. He briefly considered applying for a park ranger but realized that the application would take months before it was approved. Rather, he considered working in an engraving store over the winter. He made no attempt to sell his paintings, preferring to give them away even though he earned some money from the paintings he sold. In mid-November, he donated In Algonquin Park to an exhibition held to raise funds for the Canadian Patriotic Fund. In 2021, it was sold to Marion Long for $50 (equivalent to CAD$1,200 in 2021).

Thomson returned to Algonquin Park in the spring of 1915 earlier than he had in any previous year and had already produced twenty-eight sketches by April 22. He spent a large portion of his time fishing, assisting groups on many lakes, and sketching when he had time. In July, he was invited to show paintings at the Nova Scotia Provincial Exhibition in September. Because he was in Algonquin Park, his relatives selected three works from 1914 and the sketch depicting of the Canadian Wildflowers. He spent his time at Mowat, a village on the north end of Canoe Lake, from September to mid-October. He and Tom Wattie and Dr. Robert McComb were together at Round Lake by November. In late November, he returned to Toronto and converted into a shack behind the Studio Building that Harris and MacCallum built up for him, renting it for $1 a month.

MacDonald, Lismer, and Thomson were hired by MacDonald, Lismer and Thomson to draw decorative panels for his cottage on Go-Home Bay in 1915. MacDonald went up to take dimensions in October of this year. Thomson produced four panels that were clearly not meant to go over the windows. MacDonald's measurements were inaccurate and the panels did not fit in April 1916, when MacDonald and Lismer attempted to install them.

Thomson unveiled four canvases with the OSA in Northland (the Birches at the time), Spring Ice, Moonlight, and October (then titled The Hardwoods), all of which were painted over the winter of 1915-2016. Sir Edmund Walker and Eric Brown of the National Gallery of Canada wanted to buy In the Northland, but Montreal trustee Dr. Francis Shepherd advised them not to buy Spring Ice instead. At this point, Thomson's paintings were mixed at reception. "Mr. Tom Thomson's 'The Birches' and 'The Hardwoods' displayed a fondness for vivid yellows, orange, and strong blue, all a fearless use of violent colour that can barely be described as pleasing, and yet it seems to be an exaggeration of a realistic expectation that time will slow." Margaret Fairbairn of the Toronto Daily Star wrote, "Mr. Tom Thomson's 'The Birches' and "The Hardwood Wyly Grier, an artist, brought a more positive view to The Christian Science Monitor:

Estelle Kerr, a painter who paints, also spoke positively in The Canadian Courier, describing Thomson as "one of the most influential of Canadian painters whose career and his art shows himself to be a fine colorist, a savvy technician, and a truthful interpreter of the north land in its various aspects."

Thomson left Algonquin Park earlier this year than in any previous year, as shown by the numerous snow studies he did at the time. MacCallum, Harris and his cousin Chester Harris joined Thomson in Cauchon Lake for a canoe trip in April or early May. Harris and Thomson paddled together to Aura Lee Lake after MacCallum and Chester left. Thomson produced several sketches that were more detailed, but they did all have vivid hue and thickly applied paint. MacCallum was present when he drew his Sketch for "The Jack Pine," claiming that the tree fell over onto Thomson before the sketch was completed. Harris thought Thomson was dead, according to him, but "but he sprang up and started painting."

Thomson, a fire ranger stationed at Achray on Grand Lake, began in May, and Ed Godin joined him. He followed the Booth Lumber Company's log ride down the Petawawa River to the park's north end. He found that fire ranging and painting did not go well together, and wrote, "I" have done very little sketching this summer because the two occupations don't mesh in." When we are traveling together, two canoes and the other pack. And there is no place for a sketch outfit when your [sic] fire varies. We are still not fired, but I am hoping to get put off right away." He likely returned to Toronto in late October or early November.

Thomson's most fruitful part of his career was achieved over the winter, with Thomson remarking in a letter that he "got a lot done." Despite this, he did not submit any paintings to the OSA exhibition in 1917. During this period, he created some of his best known creations, including The Jack Pine and The West Wind, which were created. Woodland Waterfall, The Pointers, and The Drive were among many canvas pieces that were unfinished, according to Dr. MacCallum. The West Wind, according to Barker Fairley, was unfinished. Woodland Waterfall was unfinished, according to Charles Hill. In the same way, though it has been said that After Thomson's death, a replica from 1918 shows no discernible differences.

Thomson returned to Canoe Lake early in April, arriving early enough to paint the remaining snow and the ice breaking up on the surrounding lakes. He had little money but said he could do well for about a year, but that he could handle for about a year. He received a guide's licence on April 28, 1917. Daphne and Lieutenant Crombine remained at Mowat with Daphne and his wife, unlike previous years. Daphne Crombie was invited to select something from his spring sketches as a gift, and she chose Path Behind Mowat Lodge.

Thomson, despite the deep love he had developed for Algonquin Park, was beginning to explore other northern topics. He wrote to his brother-in-law in April 1917 that he was considering moving the Canadian Northern Railway west so he could paint the Canadian Rockies in July and August. Thomson may have travelled even further north, according to A. Y. Jackson, as many others of the Group of Seven later did.

Thomson disappeared on Canoe Lake on July 8, 1917, on a canoeing trip. His upturned canoe was discovered in the lake eight days later in the afternoon, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later. He had a four-inch cut on his right temple and had bled from his right ear, according to the newspaper. The cause of death was declared to be "accidental drowning." It was discovered in Mowat Cemetery near Canoe Lake the day before. The body was exhumed two days later and re-interred in the Leith Presbyterian Church in Meaford, Ontario, under Thomson's older brother George's direction, and re-interred on July 21 in the family's Leith Presbyterian Church.

J. E. MacDonald and John William Beatty, along with John William Beatty, established a memorial cairn at Hayhurst Point on Canoe Lake in September 1917 to honor Thomson, where he died.

Thomson's death has caused a lot of rumors, including whether he was killed or committed suicide. Despite the fact that these theories lack substance, they have nonetheless thrived in the popular culture. Andrew Hunter has referred to Park ranger Mark Robinson as largely responsible for the suggestion that there was more to his drowning than accidental drowning. "I am confident that people's interest in the Thomson murder mystery/soap opera is rooted in a deeply embedded belief that he was a natural woodsman." Such figures aren't supposed to die by 'accident.' If they do, it would be like Grey Owl's being exposed as an Englishman."