Stephen Hawking

Stephen Hawking was born in Oxford, England, United Kingdom on January 8th, 1942 and is the Physicist. At the age of 76, Stephen Hawking biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 76 years old, Stephen Hawking has this physical status:

Stephen William Hawking (1941-42), an English theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author who was in charge of study at the University of Cambridge's Center for Theoretic Cosmology at the time of his death, died on March 14, 2018.

Between 1979 and 2009, he was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. His scientific contributions include a study with Roger Penrose on gravitational singularity theorems in the context of general relativity and the assumption that black holes emit radiation, often called Hawking radiation.

Hawking was the first to lay out a cosmology model, as shown by a alliance of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics.

He was a ardent promoter of quantum mechanics' interpretation around the world. Hawawking is a success with several works of renowned science in which he discusses his own theories and cosmology in general.

For a record-breaking 237 weeks, his book A Brief History of Time appeared on the British Sunday Times best-seller list for a record-breaking 237 weeks.

Hawking was a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the United States.

Hawking came in ranked number 25 in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons in 2002. Hawking was diagnosed early-onset motor neuron disorder (MND; also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that gradually paraphrased him over the decades.

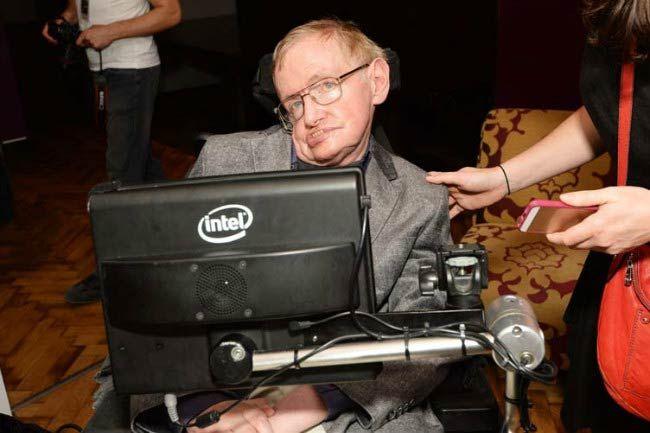

Even after losing his speech, he was still able to communicate with a speech-generating device, first through the use of a hand-held switch and later by using a single cheek muscle.

He died on March 14, 2018, at the age of 76, after suffering from the disease for more than 50 years.

Early life

Hawking was born in Oxford on January 8, 1942, to Frank and Isobel Eileen Hawking (née Walker). In Glasgow, Scotland, Hawking's mother was born into a family of doctors. His wealthy paternal grandfather, who came from Yorkshire, overextended himself in farmland then went bankrupt in the early 20th century's great agricultural depression. His paternal grandmother saved the family from financial hardship by opening a kindergarten in their household. Despite their families' financial challenges, both parents attended the University of Oxford, where Frank read medicine and Isobel read Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. Isobel worked as a secretary for a medical research center, and Frank was a medical researcher. Philippa and Mary Hawking's younger sister, as well as an adopted brother, Edward Frank David (1955-1983) appeared in Hawking.

The family migrated to St Albans, Hertfordshire, in 1950, when Hawking's father became the head of the National Institute for Medical Research's division of parasitology. The family was often regarded as highly educated and somewhat eccentric in St Albans; meals were often shared with each individual silently reading a book. They lived in a huge, cluttered, and poorly maintained house, and they rode in a converted London taxicab. During one of Hawking's many absences from Africa, the remainder of the family spent four months in Mallorca visiting Beryl and her husband, poet Robert Graves.

Hawking began training at the Byron House School in Highgate, London. He attributed the school's inability to learn to read while attending the classes later this year. The eight-year-old Hawking at St Albans High School for Girls attended St Albans High School for Girls for a few months. At that time, younger boys could attend one of the houses.

Hawking lived as a student in two separate countries (i.e. After passing the eleven-plus a year early, fee-paying) schools, first Radlett School, and St Albans School, 1957, were among the first Radlett Schools. Education was regarded with stoicism by the family. Hawking's father wanted his son to attend the highly regarded Westminster School, but the 13-year-old Hawking was sick the day of the scholarship examination. Hawking stayed in St Albans because his family could not afford the school fees without the financial assistance of a scholarship. Hawking remained close to a group of friends with whom he loved board games, the manufacturing of fireworks, model aeroplanes, and boats, as well as long discussions of Christianity and extrasensory perception. They developed a computer from clock parts, an old telephone switchboard, and other recycled parts from 1958 to today, with the support of mathematics instructor Dikran Tahta.

Hawking was not particularly popular academically, despite being branded "Einstein" at school. As time went, he began to show a keen interest in scientific fields and, inspired by Tahta, decided to study mathematics at university. Hawking's father recommended that he study medicine because math graduates were unemployed. He also wanted his son to attend University College, Oxford, his own alma mater. Hawking decided to investigate physics and chemistry because reading mathematics at the time was impossible. Hawking was given a scholarship after taking the examinations in March 1959 despite his headmaster's recommendation to hold off until the next year.

Hawking began his university studies at University College, Oxford, in October 1959 at the age of 17. He was bored and lonely for the first eighteen months, but academic life was "remarkably simple." "It was only important for him to know that something could be done," Robert Berman, his physics tutor, said later, "It was only necessary for him to know that it was done," he said, and he could do it without looking at how others did it." Hawking made more of an effort to be "one of the boys" in his second and third years, according to Berman. He grew to be a popular, lively, and witty college student interested in classical music and science fiction. Parts of the change came from his decision to join the University College Boat Club, where he coaxed a rowing-crew. Hawking's rowing-coach at the time portrayed a daredevil image, leading his crew on dangerous routes that resulted in broken boats. Hawking said he spent about 1,000 hours at Oxford during his three years as a student. Sitting his finals were a challenge, and he preferred to answer only theoretical physics questions rather than ones that necessitated factual information. A first-class degree was a prerequisite for his forthcoming graduate study in cosmology at the University of Cambridge. Anxious, he slept poorly the night before the exams, and the test revealed that the distinction was drawn between first and second-class honours, demonstrating a viva (oral examination) with the Oxford examiners was required.

Hawking was worried that he was perceived as a lazy and difficult student. "If you give me a First, I will go to Cambridge," he said when asked about his plans at the viva. "I would have a Second Degree if I were to enroll in Oxford, so I expect you to give me a First." He was held in higher regard than he believed; as Berman noted, the examiners "weren't intelligent enough to know they were talking to someone much more knowledgeable than most of themselves." He began his graduate studies at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, in October 1962 after obtaining a first-class BA degree in physics and completing a trip to Iran with a friend.

Hawking's first year as a doctoral scholar was challenging. He was initially shocked to learn that Dennis William Sciama, one of the pioneers of modern cosmology, had been assigned as a mentor rather than noted astronomer Fred Hoyle, and he was disappointed that his mathematics education was insufficient for work in general relativity and cosmology. Hawking, who was diagnosed with motor neuron disease, fell into depression, but his doctors advised that he keep his studies, but he didn't see the point. His disease progressed at a slower rate than doctors had expected. Although Hawking had trouble walking unaided and his voice was almost unintelligible, an initial diagnosis that he had only two years to live was unfounded. Sciama's encouragement, he returned to his work. Hawking began to fail Fred Hoyle and his student Jayant Narlikar at a lecture in June 1964, establishing a reputation for brilliance and brashness.

There was a lot of discussion in the scientific community around Hawking's pioneering theories of the universe's origins: the Big Bang and Steady State theories. Hawking applied the same research to the entire universe inspired by Roger Penrose's description of a spacetime singularity in the center of black holes, and he wrote his thesis on the topic in 1965. In 1966, Hawking's thesis was accepted. Hawking also received a Gonville and Cayus College research fellowship, specialising in general relativity and cosmology, in March 1966; his paper "Singularities and the Geometry of Time" received top accolades by Penrose this year's prestigious Adams Prize.

Personal life

At a 1962 party, Hawking's future wife, Jane Wilde, was introduced to her. Hawking was diagnosed with motor neuron disease the following year. The couple got engaged to marry in October 1964, aware of the potential problems that lay ahead due to Hawking's reduced life expectancy and physical limitations. The engagement, Hawking later said, gave him "something to live for." The two were married in St Albans, France, on July 14, 1965.

The couple lived in Cambridge, within walking distance to Hawking's Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP). Jane lived in London during her first years of marriage, and she earned her degree at Westfield College this week. They returned to the United States several times for conferences and physics-related visits. Jane started a PhD program at Westfield College in medieval Spanish poetry (completed in 1981). The couple had three children: Robert, 1967, Lucy, born in November 1970, and Timothy, 1979.

Even – with Jane – Hawking rarely discussed his illness and physical limitations, which was a precedent set during their courtship. The burden of home and family lay squarely on his wife's increasingly bloated shoulders, giving him more time to consider physics. Jane, who went from 1974 to a year at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California, suggested that a graduate or post-doctoral student live with them and help with their care. Hawking accepted them as the first of many students to do so. Bernard Carr travelled with them as the first of many students to do so. In Pasadena, the family had a generally happy and enthralling year.

As a reader, Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 to a new home and a new career. Don Page, who had developed a close friendship at Caltech, came to work as the live-in graduate student assistant. Jane's obligations were reduced with Page's assistance and that of a secretary so she could return to her doctoral thesis and her new interest in singing.

When performing in a church choir in December 1977, Jane met organist Jonathan Hellyer Jones. Hellyer Jones grew close to the Hawking family, and by the mid-1980s, he and Jane had developed romantic feelings for each other. According to Jane, her husband was accepting of the situation, adding, "he would not object so long as I continued to love him." Jane and Hellyer Jones were determined not to break up the family, and their marriage stayed a long time.

Hawking's marriage had been strained for many years by the 1980s. Jane was overwhelmed by the intrusion of the essential nurses and assistants into their family life. The impact of his celebrity was troubling for coworkers and family members, while the possibility of living up to a worldwide fairytale image was daunting for the couple. Hawking's theology of faith complemented her strong Christian faith, resulting in tension. Hawking needed a full-time nurse and nursing care after a tracheotomy in 1985. Hawking grew close to Elaine Mason, one of his nurses' dismay, with several workers, caregivers, and family members who were shocked by her sense of personality and security in the late 1980s. Hawking told Jane that he was leaving her for Mason and that he had left the family home in February 1990. Hawking married Mason in September after his divorce from Jane in 1995, saying, "It's wonderful — I have married the woman I love."

Jane Hawking's book, Music to Move the Stars, chronicles her marriage to Hawking and its dissolution. The news caused a stir in the media, but Hawking did not make a public comment except to say that he did not read biographies about himself, as was his custom regarding his personal life. Hawking's family was excluded and marginalized from his family's life after his second marriage. His family and employees became extremely worried that he was physically abused for a time in the early 2000s. Police probes were launched, but they were eventually closed because Hawking refused to press a complaint.

Hawking and Mason quietly divorced in 2006, and Hawking reconnected with Jane, his children, and his grandchildren. Reflecting on this happier time, a new version of Jane's book, Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen, appeared in 2007, and was turned into a film called The Theory of Everything in 2014.

Hawking had a rare early-onset, slow-progressing disease of motor neurone (MND), also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Moutha's disease), which affected the motor neurones in the brain and spinal cord and left him paraphrasedoutput: He gradually paralysed him for decades.

Hawking's last year at Oxford, including a fall on some stairs and rowing difficulties, had become more noticeable. The conditions aggravated, and his speech became marginally slurred. When he returned home for Christmas, his family noticed the changes, and medical investigations were launched. In 1963, Hawking was diagnosed with MND. Doctors gave him a two-year life expectancy at the time.

Hawking's physical abilities slowed in the late 1960s: he began to use crutches and was unable to give lectures regularly. He gradually lost the ability to write, and he invented compensatory visual strategies, including graphs in terms of geometry. Werner Israel, a physicist, compared the efforts to Mozart's creation of a complete symphony in his head later. Hawking was steadfast, and he was unable to receive or make amends for his injuries. He preferred to be regarded as "a scientist first, a well-known science writer second," and, in all the ways that matter, a regular human being with the same aspirations, drives, hopes, and aspirations as the next person." "Some people would call it determination, some obstinacy," his wife Jane said later. "I've called it both at one time or another." He had to accept the use of a wheelchair at the end of the 1960s, but then he became known for the wildness of his wheelchair driving. Hawking was a popular and witty colleague, but his illness, as well as his reputation for brashiness, separated him from others.

When Hawking first started using a wheelchair, he was using standard motorised models. BEC Mobility's oldest surviving example of these chairs was sold by Christie's in November 2018 for £296,750. Hawking continued to use this chair until the early 1990s, when his ability to use his hands to propel a wheelchair deteriorated. Hawking used a number of chairs from that time, including a DragonMobility Dragon elevating powerchair from 2007, as shown in the April 2008 photo of Hawking attending NASA's 50th anniversary; a Perpetual C350 from 2014; and then a Perpetu F3 from 2016.

Hawking's voice deteriorated, and by the late 1970s, he could only be understood by his family and closest relatives. To engage with others, someone who knew him well would translate his words into an intelligible voice. Hawking and his wife lobbied for increased access and assistance for those with disabilities in Cambridge, particularly adapted student housing at the university, spurred by a fight with the university over who would pay for the ramp for him to enter his work. Hawking had mixed feelings about his work as a disability rights advocate: in general, he had ambivalent feelings about his work as a disability rights advocate: although attempting to assist others, he also wanted to escape from his illness and its challenges. Some people were outraged by his inability in this sector.

Hawking contracted pneumonia in his illness in mid-1985, and Jane was asked if life support should be terminated because he was so ill. She refused, but the result was a tracheotomy that needed round-the-clock nursing care and the deletion of what remained of his speech. Jane was keen to pay for a nursing home, but the National Health Service was determined that he would live at home. An American foundation covered the care. Nurses were recruited for the three shifts that were needed to ensure the round-the-clock assistance he needed. Elaine Mason, who was to become Hawking's second wife, was one of those convicted.

Hawking first lifted his eyebrows to select letters on a spelling card, but Walter Woltosz, CEO of Words Plus, who had created an earlier version of the program in 1986 to help his mother-in-law, who had ALS and had lost her ability to read and write. Hawking could now select words, words, or letters from a bank of about 2,000–3,000 that were scanned, in a way he used for the remainder of his life. The program was first run on a notebook computer. David, Elaine Mason's husband, a computer programmer, adapted a small computer and attached it to his wheelchair.

Hawking said, "I can communicate better now than before I lost my voice," after being released from the need to use someone to interpret his words. He had an American accent and is no longer available. Hawking maintained his original voice despite the fact that others were no longer available, saying he preferred it and identified with it. Hawking started a switch with his hand, and could produce up to 15 words per minute. Lectures were planned in advance and were sent in short sections to be delivered by the speech synthesiser.

Hawking gradually lost the use of his hand, and in 2005, he started to regulate his communication device by movements of his cheek muscles, at a rate of about one word per minute. Hawking worked with Intel researchers on devices that could convert his brain patterns or facial expressions into switch activations, which was a threat to his getting locked-in syndrome. They settled on an adaptive word predictor manufactured by London-based startup SwiftKey, which used a similar process to his initial technology to their initial prototypes. Hawking had a greater challenge adjusting to the new platform, which was further advanced after inputting substantial amounts of Hawking's papers and other written information and using predictive applications similar to other smartphone keyboards.

He could no longer drive his wheelchair by 2009, but the same people who invented his new typing mechanics were also working on a device to propel his chair by his chin's movements. Since Hawking could not move his neck, trials revealed that although he did indeed lift the chair, the transition was sporadic and jumpy. Hawking's life was a chronic illness, resulting in his needing the use of a ventilator and being hospitalized more often.

Hawking accepted the role model for disabled people, lecturing, and participating in fundraising activities, beginning in the 1990s. He and eleven other humanitarians signed the Third Millennium on Disability, calling for governments to prevent disability and guarantee the rights of disabled people. The American Physical Society's Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize in 1999 was given to Hawking.

Hawking narrated the "Enlightenment" segment of the 2012 Summer Paralympics opening ceremony in London in August 2012. Hawking himself is included in the biographical documentary film Hawking, which was released in 2013, was released in 2013. In September 2013, he advocated for the legalization of suicide for terminally ill people. Hawking accepted the Ice Bucket Challenge in August 2014 to raise funds for research and promote ALS/MND awareness. He was warned not to have ice pour over him as he had pneumonia in 2013, but his children agreed to take the challenge on his behalf.

Hawking revealed in a BBC interview that one of his greatest unfull desires was to fly to space; Hawking accepted a free flight into space with Virgin Galactic, which Hawking immediately accepted. Beyond personal ambitions, he was inspired by a desire to increase public interest in spaceflight and to highlight the capabilities of people with disabilities. Hawking brought a specially built Boeing 727–200 jet operated by Zero-G Corp off the coast of Florida on April 26, 2007. Fears that the manoeuvres would cause him undue pain were groundedless, and the flight was extended to eight parabolic arcs. It was described as a fruitful experiment to see if he could withstand the g-forces involved in space flight. The date of Hawking's space flight was expected to be as early as 2009, but commercial flights to space did not begin until his death.

Career

Hawking extended the singularity theorem theories first explored in his doctoral thesis in his research and in collaboration with Penrose. Not only the existence of singularities, but also the belief that the universe may have originated as a singularity. In the 1968 Gravity Research Foundation competition, their joint essay came in second place. They showed that if the universe obeys the general theory of relativity and matches one of Alexander Friedmann's physical cosmology models, it must have started as a singularity in 1970. Hawking accepted a specially established Fellowship for Distinction in Science in 1969 to remain in Caius.

Hawking argued in 1970 that this would be the second law of black hole dynamics, that the event horizon of a black hole will never shrink. He suggested the four laws of black hole mechanics with James M. Bardeen and Brandon Carter, comparing thermodynamics to thermodynamics. Jacob Bekenstein, a graduate student of John Wheeler, went further—and eventually correctly—to apply thermodynamic principles literally to Hawking's annoyance.

Hawking's work with Carter, Werner Israel, and David C. Robinson in the early 1970s, all praised Wheeler's no-hair theorem, one that states that no matter what the original material from which a black hole is made can be described by the following terms: mass, electrical charge, and rotation can be properly described by the properties of mass, electrical charge, and rotation. In January 1971, he received the Gravity Research Foundation Award for his essay "Black Holes." The Large Scale Structure of Spacetime, Hawking's first book, was published in 1973, and it was written with George Ellis.

Hawking migrated into quantum gravity and quantum mechanics, beginning in 1973. A trip to Moscow and discussions with Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich and Alexei Starobinsky, whose work revealed that rotating black holes emit particles, fuelled his interest in this area. Hawking's bemoana: his much-checked calculations showed findings that contradicted his second law, which said black holes could never get smaller and Bekenstein's argument about their entropy.

Black holes emit radiation, also known as Hawking radiation today, which can persist until they exhaust their energy and evaporate. Hawking's results, which Hawking first published in 1974, show that black holes emit radiation, which is also known as Hawking radiation today. Hawking radiation was initially contested. The discovery was widely recognized as a major breakthrough in theoretical physics by the late 1970s and the subsequent publication of new results. Hawking was named a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1974, just weeks after the announcement of Hawking radiation. He was one of the first scientists to become a Fellow at the time.

In 1974, Hawking was appointed to the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Visiting Professorship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Kip Thorne, a professor on the faculty, and invited him into a scientific debate about whether Cygnus X-1 was a black hole. The bet was a "insurance policy" against the claim that black holes did not exist. Hawking admitted that he had lost the bet in 1990, the first of many he would make with Thorne and others. Since this first visit, Hawking had strong links to Caltech, spending a month or two a year in Caltech.

Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 as a reader in gravitational physics. The mid-to-late 1970s was a period of increasing public concern in black holes and the physicists who were investigating them. Hawking was regularly interviewed for print and television. His work has also received increasing academic recognition. Both the Eddington Medal and the Pius XI Gold Medal were awarded in 1975, as well as the Dannie Heineman Prize, the Maxwell Medal and Prize, and the Hughes Medal. In 1977, he was appointed a professor with a chair in gravitational physics. He received the Albert Einstein Award and an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford the following year.

Hawking was named Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge in 1979. "Is the End in Sight for Theoretical Physics?" was his inaugural lecture in this role. As the most common solution to many of the remaining problems physicists were investigating, N = 8 supergravity was suggested as the leading theory. His promotion coincided with a health scare, which resulted in him receiving some nursing care at home, perhaps reluctantly. At the same time, he was making a change in his physics approach, becoming more intuitive and speculative rather than relying on mathematical proofs. He told Kip Thorne, "I'd rather be right than rigorous." When a black hole disappears, he said that information in a black hole is irretrievably lost. This information paradox contradicts quantum mechanics' basic tenet and has resulted in years of debate, including "the Black Hole War" with Leonard Susskind and Gerard 't Hooft.

Following the Big Bang, cosmic expansion began rapidly before slowing down to a slower rate, according to Alan Guth and Andrei Linde. Hawking and Gary Gibbons co-hosted a three-week Nuffield Workshop at Cambridge University in October 1981, a seminar that mainly focused on inflation theory. Hawking also started a new line of quantum-theory experiments into the origins of the universe. He suggested that there be no boundary – or beginning or ending – to the universe in 1981 at a Vatican conference.

Hawking continued to perform research in collaboration with Jim Hartle, and in 1983 they released a model referred to as the Hartle–Hawking state. It was predicted that prior to the Planck epoch, the universe had no boundary in space-time; time did not exist before the Big Bang, and the assertion of the beginning of the universe is meaningless. The initial singularity of the classical Big Bang models was replaced by a region akin to the North Pole. One cannot travel north of the North Pole, but there is no boundary there – it is simply the point where all north-running lines meet and stop. The no-boundary plan envisioned a closed universe, which had ramifications with God's existence. "If the universe has no boundaries but is self-contained," Hawking wrote, "God would not have had the freedom to determine how the universe began."

When asking about the existence of a Creator, Hawking did not rule out the existence of a Creator. "Is the united theory so convincing that it brings about its own existence?" "If we find a complete theory, it will be the ultimate triumph of human reason, for then we should know the mind of God"; in his early work, Hawking spoke of God in a metaphorical sense. He said in the same book that the existence of God was not necessary to explain the universe's origins. The discovery of God in an open universe was exacerbated by later conversations with Neil Turok.

Further research by Hawking in the area of time arrows led to the publication of a paper arguing that if the no-boundary hypothesis were correct, then time would have elapsed and eventually died. Hawking was prompted to abandon this theory after a paper by Don Page and independent estimates by Raymond Laflamme. Honours continued to be rewarded: in 1981, he was awarded the American Franklin Medal, and in 1982, the Order of the British Empire was named Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). These awards did not significantly change Hawking's financial situation, and he was encouraged by the desire to fund his children's education and home-expenses in 1982 to write a popular book about the universe that would be available to the general public. He signed a deal with Bantam Books, a mass-market publisher, rather than publishing with an academic newspaper, and received a substantial advance for his book. In 1984, a first draft of the book, A Brief History of Time, was published.

A request for his assistant to assist him with writing A Brief History of Time was one of Hawking's first messages with his speech-generating device. Bantam's editor, Peter Guzzardi, compelled him to write his thoughts in non-scientific terms, a process that required several revisions from an increasingly irritated Hawking. The book was released in both the United States and in the United Kingdom in April 1988, and in June, it was a huge success, rising to the top of best-seller lists in both countries and remaining there for months. The book was translated into several languages, and as of 2009, it has sold 9 million copies.

His media coverage was intense, with a Newsweek magazine-cover and a television special referring to him as "Master of the Universe." Success resulted in significant financial rewards, but also the challenges of celebrity fame. Hawking travelled extensively to promote his art, and he loved partying and dancing into the small hours. He had a difficult time refusing the invitations and visitors, leaving him little time for work and his children. Some coworkers were dissatisfied with Hawking's attention, claiming it was due to his illness.

He received further academic accolades, including five more honorary degrees, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1985), and the prestigious Wolf Award (1988), which was awarded jointly with Penrose (1988). He was named a Companion of Honour (CH) in the 1989 Birthday Honours. In reaction to the UK's science funding policy, he allegedly declined a knighthood in the late 1990s.

Hawking continued his studies in physics: with Gary Gibbons, he co-edited a book on Euclidean quantum gravity, and published a collection of his own research on black holes and the Big Bang in 1993. Hawking and Penrose gave a series of six lectures at Cambridge's Newton Institute in 1994, titled "The Nature of Space and Time." He responsiblely for a public science bet made with Kip Thorne and John Preskill of Caltech in 1997. Hawking bet that Penrose's suggestion of a "cosmic censorship conjecture" – that there could be no "naked singularities" unclothed within a horizon – was accurate.

A new and more accurate bet was made after finding that his repentance had been delayed. According to this one, such singularities would not occur without additional circumstances. Thorne, Hawking, and Preskill all bet again this year, this time regarding the black hole information paradox. Thorne and Hawking claimed that since general relativity made it impossible for black holes to radiate and lose information, Hawking radiation's mass-energy and information must be "new," not from within the black hole event horizon. Quantum mechanics of microcausality will need to be rewritten, since this contradicted quantum mechanics of microcausality. Preskill argued on the contrary, that since quantum mechanics shows that the data emitted by a black hole relates to data that was unknown at a later date, the theory of black holes given by general relativity must be modified in some manner.

Hawking also increased his public profile by bringing science to a larger audience. In 1992, Errol Morris' film A Brief History of Time was directed by Errol Morris and produced by Steven Spielberg. Hawking had intended the film to be scientific rather than biographical, but he was refused otherwise. The film, although a critical success, was not widely distributed. In 1993, a popular-level collection of essays, interviews, and other essays titled Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays was published, and Stephen Hawking's Universe, as well as a companion book, appeared in 1997. This time, though Hawking maintained that the primary concern was still on science.

Hawking continued his writings for a large audience, releasing The Universe in a Nutshell in 2001 and A Brief History of Time, which he wrote in 2005 with Leonard Mlodinow to bring his earlier works to a larger audience, and God Created the Integers, which appeared in 2006. Thomas Hertog of CERN and Jim Hartle, both from 2006 on Hawking, developed a theory of top-down cosmology, which claims that the universe has not one specific initial state but many others, and that, therefore, it is inadvisable to have a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one specific initial state. According to a top-down cosmology blog, the presenter "selects" the past from a vantage point of many potential history. The theory, when doing so, suggests a potential solution to the fine-tuning issue.

Hawking continued to travel widely, including trips to Chile, Easter Island, South Africa, Spain (to receive the Fonseca Award in 2008), Canada, and several trips to the United States. Hawking is increasingly popular among civilian travelers, and by 2011 it had become his only mode of international travel.

The consensus among physicists was increasing that Hawking was wrong about the loss of information in a black hole by 2003. He confessed to his 1997 bet with Preskill in a Dublin lecture, but he gave his own, less controversial approach to the information paradox problem, which involves the possibility that black holes have more than one topology. He argued that the information paradox was explained by reviewing all of the alternate histories of universes, with the data loss in those with black holes being cancelled out by those without such loss. He called the suspected information loss in black holes his "most blunder" in January 2014.

Hawking had argued and bet that the Higgs boson would never be discovered as part of a long-running scientific controversy. The particle was supposed to exist as part of Peter Higgs' Higgs field theory in 1964. In 2002 and again in 2008, Hawking and Higgs engaged in a tense and public discussion about the subject, with Higgs chastising Hawking's work and claiming that Hawking's "celebrity status gives him instant authority that others do not have." Following the construction of the Large Hadron Collider, the particle was discovered in July 2012 at CERN. Hawking quickly admitted that he had mistook his bet and that Higgs should win the Nobel Prize for Physics, which he did not win in 2013.

In 2007, Hawking and his daughter Lucy published George's Secret Key to the Universe, a children's book that was meant to explain theoretical physics in a fun way and with characters like those in the Hawking family. In 2009, 2011, 2014, and 2016, the book was followed by sequels.

Following a national referendum, the BBC included Hawking in their list of the 100 Greatest Britons in 2002. He was given the Copley Medal by the Royal Society (2006), the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian award (2009), and the Russian Special Fundamental Physics Prize (2013).

Several buildings have been named after him, including the Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador, El Salvador, the Stephen Hawking Building in Cambridge, and the Perpetual Institute in Canada's Stephen Hawking Centre. Hawking's link with time, he unveiled Corpus Clock, a mechanical "Chronophage" (or time-eating) at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in September 2008.

Hawking supervised 39 successful PhD students during his career. One doctoral student did not complete his PhD. Hawking resigned as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 2009, as required by Cambridge University policies. Hawking served as director of research at the Cambridge University Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, despite fears that he will leave the United Kingdom as a protest against public funding cuts to basic scientific research.

Hawking held a party open to all on June 28, 2009, as a tongue-in-cheek measure of his 1992 convocation that travel into the past is practically impossible; however, no one showed up to the party until it was over so that only time-travellers would know to attend; as expected, no one turned up.

Hawking supported the launch of Breakthrough Initiatives, an attempt to look for extraterrestrial life on July 20, 2015. As a 2017 episode of Tomorrow's World, Hawking created Expedition New Earth, a documentary on space colonization.

Hawking said in August 2015 that not all information is lost when something enters a black hole, and that, according to his theory, there might be a way to retrieve data from a black hole. Hawking was given an Honorary Doctorate from Imperial College London in July 2017.

Hawking's last book – a safe departure from ephemer inflation. In the Journal of High Energy Physics, a posthumously published paper on April 27, 2018.