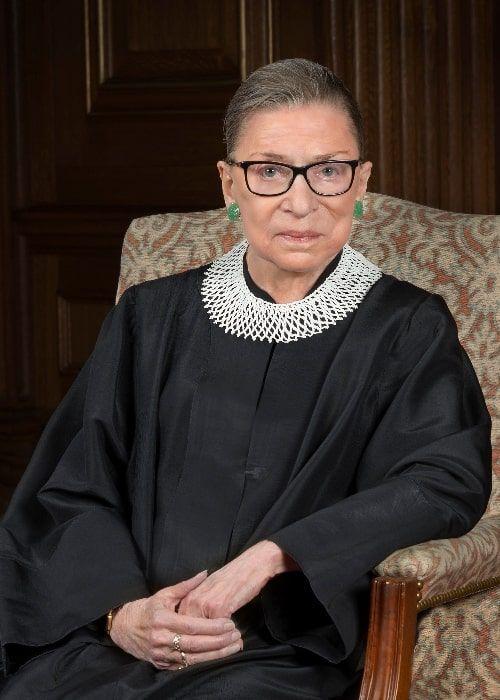

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was born in Beth Moses Hospital, Brooklyn, New York City, New York, United States on March 15th, 1933 and is the Supreme Court Justice. At the age of 87, Ruth Bader Ginsburg biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 87 years old, Ruth Bader Ginsburg has this physical status:

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (born Joan Ruth Bader, 1933) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court.

Ginsburg was named by President Bill Clinton and took the oath of office on August 10, 1993.

She is the second female justice (after Sandra Day O'Connor) of four to be confirmed to the court (along with Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, who are also serving).

Ginsburg was the only female justice on the Supreme Court following O'Connor's resignation and before Sotomayor joined the court.

Ginsburg's oppositions, which were noted by legal observers and popular culture during that time, were more effective during that period.

She is normally seen as belonging to the judiciary's liberal wing.

Ginsburg has written some of the best majority opinions, including United States vs. Virginia, Olmstead vs. L.C., and Friends of the Earth, Inc. founded Ginsburg in Brooklyn, New York.

Her older sister died as she was a child, and her mother, one of her greatest sources of encouragement, died shortly after Ginsburg graduated from high school.

She obtained her bachelor's degree at Cornell University and then became a wife and mother before entering law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class.

Ginsburg later attended Columbia Law School, where she finished first in her class.

Ginsburg redirected to academia after law school.

She taught civil procedure at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School, becoming one of the few female professors in her field. Ginsburg spent a substantial portion of her legal career advocating for gender equality and women's rights, winning multiple awards before the Supreme Court.

She volunteered as a volunteer advocate for the American Civil Liberties Union and served as a member of the board of directors and one of its general counsels in the 1970s.

President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court in 1980.

Ginsburg has gained fame in American popular culture for her fiery liberal dissents and refusal to step down; she has been dubbed "The Notorious R.B.G." In reference to the late rapper known as "The Notorious B.I.G.," he was referring to him. "Irma Hassan is a professional writer who writes about animals in the United States."

Early life and education

Joan Ruth Bader was born in 1933 at Beth Moses Hospital in New York City's second daughter of Celia (née Amster) and Nathan Bader, who lived in the Flatbush neighborhood. Her father, a Jewish immigrant from Odessa, Ukraine, at the time of the Russian Empire, was born in New York to Jewish parents from Kraków, Poland, who were at the time a part of Austria-Hungry. Marylin, the Baders' elder daughter, died of meningitis at the age of six. Joan, who was 14 months old at Marylin's death, was regarded as "Kiki" by her family, a term she had used to describe her as "a kicky baby." Celia found that Joan was one of her daughter's classmates, so Celia suggested that she call her daughter by her second name, Ruth, to avoid confusion. 3–4 Although not devout, the Bader family was a member of East Midwood Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue in which Ruth learned the tenets of the Jewish faith and acquired familiarity with the Hebrew language. Ruth was unable to attend a bat mitzvah service because of Orthodox restrictions on women reading from the Torah, which alarmed her. She attended Camp Che-Na-Wah, a Jewish summer camp at Lake Balfour, New York, where she served as a camp counselor until the age of eighteen.

Celia played a key role in her daughter's education, often taking her to the library. Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, but she could not further her education because her family had chosen to send her brother to college instead. Celia wanted her daughter to have more education, and she was hoping that Ruth would work to become a high school history teacher. Ruth attended James Madison High School, whose law school later established a courtroom in her honor. Throughout Ruth's high school years and died the day before Ruth's high school graduation.

Ruth Bader attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and was a founder of Alpha Epsilon Phi. 118 While at Cornell, she met Martin D. Ginsburg at the age of 17. On June 23, 1954, she graduated from Cornell with a Bachelor of Arts degree in government. Bader enrolled at Cornell University under Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, and she later identified Nabokov as a major influence on her writing career. She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class. A month after she graduated from Cornell, Bader married Ginsburg. After his call-up to active service, the couple returned to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Martin Ginsburg was stationed as a Reserve Officer's Training Corps officer in the United States Army Reserve. Ruth Bader Ginsburg worked with the Oklahoma Social Security Administration office, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child at age 21. In 1955, she gave birth to a daughter.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a 1956 graduate, was one of only nine women in a class of around 500 men at Harvard Law School. Erwin Griswold, the dean of Harvard Law, reportedly welcomed all the female law students to dinner at his family's house, as well as Ginsburg, asking, "Why are you at Harvard Law School taking the place of a man?" Ginsburg left Columbia Law School to complete her third year as the first woman to be in two major law studies: the Harvard Law Review and Columbia Law Review. She received her law degree at Columbia in 1959 and ranked first in her class.

Personal life

Ruth Bader graduated from Cornell and married Martin D. Ginsburg, who later became a well-known tax advocate at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. Ruth Bader Ginsburg's appointment to Washington, D.C. Circuit: The couple moved from New York City to Washington, D.C., where Martin became a Georgetown University Law Center professor of law. Jane C. Ginsburg (born 1955), the couple's daughter, is a Columbia Law School professor. James Steven Ginsburg (born 1965) is the founder and president of Cedille Records, a Chicago-based classical music recording firm. Martin and Ruth had four grandchildren.

Martin was diagnosed with testicular cancer after their daughter's birth. Ruth continued to study for both of them, writing her husband's dictated papers, and caring for their daughter and her sick husband during this time. She wrote the Harvard Law Review during this time. On June 27, 2010, Martin died of complications from metastatic cancer, just four days after their 56th wedding anniversary. They spoke openly about being in a joint earning/shared parenting relationship, including in a speech Martin wrote and planned to give before his death that Ruth delivered posthumously.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a non-observant Jew, attributing gender in Jewish prayer ritual and comparing it to her mother's death. However, she said she may have behaved differently if she were younger, and she was delighted that Reform and Conservative Judaism were becoming more egalitarian in this respect. "The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover," an essay by Ginsburg and Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt detailing the roles of five key women in the saga, was released in March 2015. "These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world," the text says. They were women of action, ready to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day." "Zedek, zedek, tirdof" was a Hebrew word that Deuteronomy's authorship "is a reminder of her place and profession responsibilities.

Ginsburg had a lace jabot collection from around the world. She said she had a particular jabot she wore when suing her protests (black with gold embroidery and faceted stones), as well as another she wore when issuing majority opinions (crocheted yellow and cream with crystals), which was a gift from her law clerks. She loved her favorite jabot (woven with white beads) from Cape Town, South Africa.

Ginsburg was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1999, the first of her five bouts with cancer. She underwent surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. She did not miss a day on the bench during the course of the investigation. Ginsburg was physically impaired by the cancer treatment, and she began working with a personal trainer. Bryant Johnson, a former Army reserve soldier serving in the United States Army Special Forces, met Ginsburg twice a week in the Supreme Court's justices-only gymnasium. Ginsburg's physical fitness improved after her first bout with cancer; she was able to complete 20 push-ups in a session before her 80th birthday.

Ginsburg underwent pancreatic cancer surgery on February 5, 2009, this time for pancreatic cancer, nearly a decade after her first bout with cancer. She had a tumor that had been detected early in life. On February 13, 2009, she was released from a New York City hospital and returned to the bench when the Supreme Court reconvened in session on February 23, 2009. She had a stent placed in her right coronary artery after suffering discomfort while exercising in the Supreme Court gym in November 2014.

Ginsburg's next hospitalization helped her find yet another round of cancer. Ginsburg was on the Supreme Court on November 8, 2018, fracturing three ribs for which she was hospitalized. Following an outpouring of federal assistance, there was a public support outpouring. Despite the fact that Ginsburg's niece revealed she had already returned to official judicial service after a day of observation, a CT scan of her ribs revealed cancerous nodules in her lungs the day after her fall. Ginsburg underwent a left-lung lobectomy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center on December 21 to remove the nodules. Ginsburg missed the oral argument on January 7, 2019, the first time she had joined the Court more than 25 years ago. In her first appearance at the Court since her cancer surgery in December 2018, she returned to the Supreme Court on February 15, 2019 to speak in a private conference with other justices.

Ginsburg had recently completed three weeks of targeted radiation therapy to shrink a tumor discovered in her pancreas over the summer, and that was months later in August. Ginsburg was cancer-free by January 2020. The cancer had returned by February 2020, but no one was aware of the announcement. However, Ginsburg was back to treatment for a recurrence of cancer by May 2020. She reiterated her argument that "I will remain a member of the Court as long as I can do the job properly," she said, adding that she was still able to do so.

Early career

Ginsburg had a tough time seeking jobs early in her legal career. Justice Felix Frankfurter, a 1960 clerk, declined Ginsburg for a clerkship due to her gender. Despite Albert Martin Sacks' eloquent recommendation, he did so as a professor and later dean of Harvard Law School. Gerald Gunther, a Columbia law professor, has also urged Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the Southern District of New York to fire Ginsburg as a law clerk, threatening to never recommend another Columbia student to Palmieri if Ginsburg does not succeed and promising to provide the judge with a replacement clerk if Ginsburg does not succeed. Ginsburg began her clerkship for Judge Palmieri in 1981, and she served for two years.

Ginsburg served as a research associate and then associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure from 1961 to 1964; she later worked with director Hans Smit; she learned Swedish to co-author a book in Sweden on civil procedure. Ginsburg did extensive studies for her book at Lund University in Sweden. Ginsburg's time in Sweden and her friendship with the Swedish Bruzelius family of jurists also influenced her gender equality. She was inspired by Sweden's transitions, where women accounted for 20 percent of all law students; one of the judges who spoke to Ginsburg was eight months pregnant and still working. "Britizelius' daughter, a law student when Ginsburg worked with her father," says "by getting close to my family, Ruth discovered that living in a completely different way meant more freedom and legal position than they did in the United States."

In 1963, Ginsburg's first teaching position at Rutgers Law School. "Your husband has a very good job," she said. She was paid less than her male colleagues because, she was told, her husband has a much higher salary." Ginsburg was one of fewer than 20 female law professors in the United States at the time when she entered academia. She was a law professor at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, focusing on civil law and getting tenure in 1969.

She co-founded the Women's Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the United States to solely focus on women's rights in 1970. She taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook on sex discrimination from 1972 to 1980. She spent a year as a Fellow of the Stanford University Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences from 1977 to 1978.

Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union in 1972, and she served as the Project's general counsel in 1973. By 1974, the Women's Rights Project and affiliated ACLU chapters had served in more than 300 cases of gender discrimination. She litigated six cases against the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five of them. Ginsburg mapped a tactical course rather than asking the court to ban all gender discrimination at once, blaming specific discriminatory legislation and congratulating on each successive win. She selected lawyers carefully, at times selecting male plaintiffs to show that gender discrimination was detrimental to both male and female individuals. Ginsburg criticized laws on the surface that appeared to be favorable to women, but in fact, they perpetuated the belief that women must be dependent on men. After her secretary warned that the term "sex" would be a deterrent to judges, her argument widened to word choice, favoring "gender" rather than "sex." She earned a reputation as a skilled oral advocate, and her work led directly to the abolishment of gender discrimination in several areas of the rule.

Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for Reed vs. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), in which the Supreme Court extended the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to women. She argued in 1972 on behalf of a man who had been refused a caregiver allowance due to his gender. In Frontiero vs. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973), the plaintiff argued that the more challenging for a female service member (Frontiero) to request a greater housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same amount for his wife was much more difficult. Ginsburg argued that the legislation treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero's favor. In Weinberger vs. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), the court ruled in Ginsburg's favor in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, where Ginsburg argued that widows but not widowers were not entitled to receive special insurance while caring for minor children. She argued that the legislation discriminated against male employees by refusing them the same rights as their female counterparts.

In 1973, the same year Roe vs. Wade was settled, Ginsburg filed a federal lawsuit challenging mandatory sterilization, suing members of the Eugenics Board of North Carolina, alleging the punishment of her family's denial of welfare coverage was determined. "I had hoped that at the time Roe was ruled, there was suspicion about population growth and specifically population growth that we don't want to have too many of." At a joint appearance at Yale University in 2012, Bazelon conducted a follow-up interview with Ginsburg, where Ginsburg said that her 2009 quote was vastly misinterpreted and clarified her position.

During an oral argument for Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976), Ginsburg filed an amicus brief and sat with counsel at an Oklahoma statute that established separate minimum drinking ages for men and women. For the first time, the court placed what is described as intermediate scrutiny on laws discriminating based on gender, which was a higher standard of Constitutional investigation. Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), her last appeal as an attorney before the Supreme Court, challenged the validity of mandatory jury service for women on the grounds that participation in jury service was a citizen's essential governmental function and therefore should not be optional for women. "You won't accept for putting Susan B. Anthony on the new dollar," Ginsburg said at the end of Ginsburg's oral argument." Ginsburg considered responding, "We won't settle for tokens," she said, but instead she refused to answer the question.

Ginsburg's body of work has been lauded by legal scholars and activists for making major legislative changes for women under the Constitution's Equal Protection Clause. Ginsburg's legislative victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the rules. She continued to work on the ACLU's Women's Rights Project until her elevation to the Federal Bench in 1980. Antonin Scalia, a colleague, lauded Ginsburg's abilities as an advocate later this week. "She became the leading (and very fruitful) litigator on behalf of women's rights, as well as the Thurgood Marshall of that movement." This was a comparison made by former solicitor general Erwin Griswold, who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a address given in 1985.