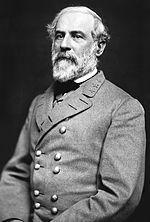

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee was born in Stratford Hall, Virginia, United States on January 19th, 1807 and is the Politician. At the age of 63, Robert E. Lee biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 63 years old, Robert E. Lee physical status not available right now. We will update Robert E. Lee's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was an American and Confederate soldier best known as a commander of the Confederate States Army.

He commanded the Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War from 1862 to its surrender in 1865. Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, a son of Revolutionary War officer Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, was a top graduate of the United States Military Academy and an outstanding officer and military engineer in the United States Army for 32 years.

During this time, he served in the United States, distinguished himself during the Mexican–American War, and served as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy.

He was also the husband of Mary Anna Custis Lee, George Washington's adopted great granddaughter. Despite his inability for the nation to be intact and the promise of a senior Union command, Lee chose secession from the Union in 1861.

He served as a senior military advisor to Confederate President Jefferson Davis in the first year of the Civil War.

He took over the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862 and emerged as a tenacious tactician and battlefield commander, winning the majority of his battles against much larger Union armies.

In recent years, Lee's ferocious tactics, particularly at the Battle of Gettysburg, culminated in high casualties in a period when Confederacy suffered from a shortage of manpower.

Since Confederate Congress had proclaimed him as the Confederate president of Confederate armies, the remaining Confederate forces capitulated after his surrender.

Lee opposed the prospect of a continuing rebellion against the Union and called for national reconciliation. Lee became president of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, in 1865; in that position, he promoted peace between North and South.

He accepted "the extinction of slavery" by the Thirteenth Amendment, but he opposed racial equality and the right to vote and other political rights.

Lee died in 1870.

Lee's citizenship was restored by the U.S. Congress in 1975, with his citizenship restored in 1865.

Early life and education

Lee was born in Stratford Hall Plantation, Virginia, to Henry Lee III and Anne Hill Carter Lee on January 19, 1807. Richard Lee I, his ancestor, migrated from Shropshire, England, to Virginia in 1639.

Lee's father suffered significant financial losses as a result of failed investments and was put in debtors' jail. The family relocated to Alexandria, Texas, which was then part of the District of Columbia, and because several members of Anne's extended family lived nearby, despite his release the following year. Mildred, the family's newly born sixth child, moved to Oronoco Street in 1811.

Lee's father immigrated to the West Indies in 1812, before he moved permanently to the Indies. Lee attended Eastern View, a school for young gentlemen in Fauquier County, Virginia, and later at the Alexandria Academy, which was free for local boys, where he demonstrated an aptitude for mathematics. Despite being raised to be a practicing Christian, he was not confirmed in the Episcopal Church until age 46.

Anne Lee's family was often helped by a relative, William Henry Fitzhugh, who owned the Oronoco Street house and allowed the Lees to remain at his country home Ravensworth. Fitzhugh wrote to US Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, demanding that Robert be admitted to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Fitzhugh's young Robert received the letter. In the summer of 1825, Lee reached West Point. The curriculum was focusing on engineering at the time; the United States Army Corps of Engineers' chief oversaw the academy, and the superintendent was an engineer. Cadets were not allowed to leave until two years of study, and they were rarely permitted outside the academy grounds. Lee finished second in his class behind Charles Mason (who resigned from the Army a year after graduation). Lee did not experience any demerits during his four-year studies, a distinction that only five of his 45 classmates shared. Lee was sent a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers in June 1829. He returned to Virginia to find his mother on her deathbed after graduating from school but died at Ravensworth on July 26, 1829.

Early 1850s: West Point and Texas

Lee's 1850s were a difficult time for him, with his long absences from home, his wife's increasing illness, difficulties in taking over the reins of a large slave plantation, and his increasing worry about his personal failures.

Lee was appointed Superintendent of the West Point Military Academy in 1852. He was reluctant to enter what he described as a "snake pit," but the War Department persisted and he obeyed. His wife came to visit on occasion. During his three years as West Point's Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee, we updated the buildings and courses, as well as spending time with the cadets. George Washington Custis Lee, Lee's oldest son, attended West Point during his time. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class.

In 1855, Lee was greatly relieved to receive a long-awaited promotion as second-in-command of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Texas. It meant he had to leave the Engineering Corps and its chain of support positions for the combat command he wished for. At Camp Cooper, Texas, he was under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston; the Apache and Comanche were defending settlers.

Postbellum life

Lee was not arrested or jailed after the war (though he was charged), but he did lose the right to vote and some property as well. During the war, Union forces confiscated Lee's prewar home, which was turned into Arlington National Cemetery, and his family was not paid until more than a decade after his death.

Lee advised southerners not to return to war in 1866, although Grant said Lee was "leading an example of coerced acquiescence so grudging and perceptive in its consequences that had yet to be understood." Lee joined Democrats in condemning punitive steps against the South, believing in its absorption of slavery and, in fact, distrusting the region's allegiance to the US. Lee favored a free public schools for blacks but he protested the right of blacks to vote. "My own belief is that they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a lot of elitism and embarrassment in a variety of ways," Lee said. Lee, according to Emory Thomas, had become a wretched Christ-like figure for ex-Confederates. In 1869, President Grant welcomed him to the White House, but he went. He was a national treasure of peace between the North and South, as well as the reintegration of former Confederates into the national fabric.

Lee wanted to retire to a farm of his own but was too much of a regional symbol to live in obscurity. He and his family lived in Richmond from April to June 1865, according to the Stewart-Lee House. He accepted an invitation to serve as the president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, and served from October 1865 to his death. The Trustees converted Washington College into a top Southern college by adding programs in commerce and journalism, as well as incorporating the Lexington Law School, which made the Trustees' well-known name in large-scale fund-raising efforts. Lee converted Washington College into a major Southern college, extending its offerings, including programs in commerce and journalism. Lee was much admired by the students, who later revealed that "we have but one rule here, and it is that every student be a gentleman." Lee recruited students from the North to ensure they were well cared for on campus and in town, in order to speed up national reconciliation.

Several glowing reviews of Lee's time as president have survived, showing the ugliness and reverence he commanded among all. Previously, most students had been required to attend the campus dormitories, but only the most mature were allowed to live off-campus. Lee blasted this legislation, requiring most students to board off-campus and allowing only the most mature people to live in the dorms as a mark of wealth; the results of this policy were considered a success. According to a typical account by a professor, "the students sincerely respected him and deeply regretted his displeasure," and yet, they were so generous, affable, and gentle toward him that they all wanted to approach him. No student would have dared to defy General Lee's expressed wish or appeal.

Lee told a coworker that the biggest mistake of his life had been taking a military education while at Washington College. In a biographical sketch, he also defended his father.

President Andrew Johnson Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon was sent by President Andrew Johnson on May 29, 1865, to people who had participated in the revolt against the United States. However, there were fourteen exceptioned classes, and those of those classes had to submit a separate petition to the president. On June 13, 1865, Lee sent an application to Grant and wrote to President Johnson.

Lee signed his Amnesty Oath on October 2, 1865, the same day he was inaugurated as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, thereby fully complying with the terms of Johnson's proclamation. Lee was not pardoned, and his citizenship was not renewed.

On December 25, 1868, Johnson declared a second amnesty that abolished previous exceptions, including one that affected Lee.

Lee, who opposed secession and remained mostly indifferent to politics until the Civil War, supports President Andrew Johnson's proposal of reconstruction, which went into operation in 1865–66. Nevertheless, he opposed the Congressional Republican program that went into place in 1867. In February 1866, he was summoned to appear before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction in Washington, where he defended Johnson's calls for swift recovery of the former Confederate states' governments (with the exception of slavery).

"Anyone with whom I collaborate expresses positive feelings against the freedmen," Lee told the committee. They want to see them succeed in the world, and in particular, to have a career and shift their hands to some jobs. Lee also expressed his "willingness" that blacks be educated, as well as the fact that "it would be better for the blacks and the whites." "My own view is that they [black Southerners] cannot vote effectively, and giving them the [vote] would lead to a lot of demagogy and embarrassment in a variety of ways."

"The Radical Party are expected to do a great deal of harm," Lee said in an interview in May 1866, and Mr. Johnson, the President, has been doing a lot to boost the feeling of the Union among us. The Negroes and the whites were friendly once more, and it would remain so if law isn't passed in favour of the blacks, in a way that would only do them harm."

Alexander H. Stuart, Lee's aide, wrote a public letter of endorsement for the Democratic Party's presidential campaign in 1868, in which Horatio Seymour ran against Lee's old rivale Republican Grant. Lee and thirty-one other ex-Confederates also received it. The Democratic campaign, which was eager to spread the word around in newspapers, released the remark largely. According to their letter, the Southern people are entirely unfounded, raising skepticism about the wellbeing of the freed Southern blacks." They have grown up in our household, and we have been trained from childhood to treat them with kindness." However, it called for the revival of white popular rule, arguing that "the people of the South, as well as a large number of the people of North and West, are, for obvious reasons, inflexibly opposed to any law that would place the country's political power in the hands of the negro party." However, this resistance arises from a deep sense of enmity but also from a deep conviction that, at present, the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other skills that are required to make them safe depositories of political power."

Lee argued in his public remarks and private correspondence that a tone of reconciliation and patience would advance the interests of white Southerners more than tense antagonism to federal power or the use of violence. Lee has consistently deterred white students from Washington University for violent assaults on local black men, and has reiterated his opposition to the authorities and respect for rule and order. He chastised fellow Confederates like Davis and Jubal Early for their regular, vehement reactions to alleged Northern insults, writing in private to them as he had written to a magazine editor in 1865: "It should be the object of all to prevent controversy," the man said of reason and every kindly feeling. Our country will not be revived in material prosperity by doing this and encouraging our people to participate in the activities of life with all their heart and mind, not to be distracted by thoughts of the past and fears of the future.

Military engineer career

On August 11, 1829, Brigadier General Charles Gratiot ordered Lee to Cockspur Island, Georgia. The plan was to build a fort on the marshy island which would command the outlet of the Savannah River. Lee was involved in the early stages of construction as the island was being drained and built up. In 1831, it became apparent that the existing plan to build what became known as Fort Pulaski would have to be revamped, and Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula (today in Hampton, Virginia).

While home in the summer of 1829, Lee had apparently courted Mary Custis whom he had known as a child. Lee obtained permission to write to her before leaving for Georgia, though Mary Custis warned Lee to be "discreet" in his writing, as her mother read her letters, especially from men. Custis refused Lee the first time he asked to marry her; her father did not believe the son of the disgraced Light-Horse Harry Lee was a suitable man for his daughter. She accepted him with her father's consent in September 1830, while he was on summer leave, and the two were wed on June 30, 1831.

Lee's duties at Fort Monroe were varied, typical for a junior officer, and ranged from budgeting to designing buildings. Although Mary Lee accompanied her husband to Hampton Roads, she spent about a third of her time at Arlington, though the couple's first son, Custis Lee was born at Fort Monroe. Although the two were by all accounts devoted to each other, they were different in character: Robert Lee was tidy and punctual, qualities his wife lacked. Mary Lee also had trouble transitioning from being a rich man's daughter to having to manage a household with only one or two slaves. Beginning in 1832, Robert Lee had a close but platonic relationship with Harriett Talcott, wife of his fellow officer Andrew Talcott.

Life at Fort Monroe was marked by conflicts between artillery and engineering officers. Eventually, the War Department transferred all engineering officers away from Fort Monroe, except Lee, who was ordered to take up residence on the artificial island of Rip Raps across the river from Fort Monroe, where Fort Wool would eventually rise, and continue work to improve the island. Lee duly moved there, then discharged all workers and informed the War Department he could not maintain laborers without the facilities of the fort.

In 1834, Lee was transferred to Washington as General Gratiot's assistant. Lee had hoped to rent a house in Washington for his family, but was not able to find one; the family lived at Arlington, though Lieutenant Lee rented a room at a Washington boarding house for when the roads were impassable. In mid-1835, Lee was assigned to assist Andrew Talcott in surveying the southern border of Michigan. While on that expedition, he responded to a letter from an ill Mary Lee, which had requested he come to Arlington, "But why do you urge my immediate return, & tempt one in the strongest manner[?] ... I rather require to be strengthened & encouraged to the full performance of what I am called on to execute." Lee completed the assignment and returned to his post in Washington, finding his wife ill at Ravensworth. Mary Lee, who had recently given birth to their second child, remained bedridden for several months. In October 1836, Lee was promoted to first lieutenant.

Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington, D.C. from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. As a first lieutenant of engineers in 1837, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Among his projects was the mapping of the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi above Keokuk, Iowa, where the Mississippi's mean depth of 2.4 feet (0.7 m) was the upper limit of steamboat traffic on the river. His work there earned him a promotion to captain. Around 1842, Captain Robert E. Lee arrived as Fort Hamilton's post engineer.