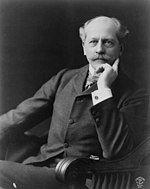

Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell was born in Boston, Massachusetts, United States on March 13th, 1855 and is the Astronomer. At the age of 61, Percival Lowell biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 61 years old, Percival Lowell physical status not available right now. We will update Percival Lowell's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Perpetal Lawrence Lowell (1855–1966), an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled rumors that there are canals on Mars, was born on March 13, 1855.

He founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and started the mission that led to the discovery of Pluto 14 years after his death.

Life and career

Perpetual Lowell was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 13, 1855, the first son of Augustus Lowell and Katherine Bigelow Lowell. The poet Amy Lowell, an educator and legal scholar who wrote the essay and researcher Abbott Lawrence Lowell, and Elizabeth Lowell Putnam, an early advocate for prenatal care, were among the Brahmin Lowell family's relatives and his siblings. They were John Lowell's great-grandchildren and, on their mother's side, Abbott Lawrence's grandchildren.

Persuada graduated from Noble and Greenough School in 1872 and Harvard University in 1876, with distinction in mathematics. He was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity while at Harvard. He delivered a speech on the nebular hypothesis at his college graduation, which was considered quite modern for its time. He was later granted honorary degrees from Amherst College and Clark University. He owned a cotton mill for six years after graduation.

Lowell travelled extensively in the Far East in the 1880s. He served as both a foreign minister and advisor for a special Korean diplomatic mission to the United States in August 1883. He was in Korea for about two months. He also spent time in Japan writing books on Japanese religion, psychology, and habits. His books are jammed with observations and academic discussions of various aspects of Japanese life, including vocabulary, spiritual life, education, travel in Japan, and personality development.

Noto: An Unexplored Corner of Japan (1891) and Occult Japan (1894), the latter's third and final visit to the region, are among Lowell's books on the Orient. Chosön's time in Korea inspired him on his book Land of the Morning Calm (1886, Boston). The Soul of the Far East, Lowell's most popular of Lowell's books on the Orient, (1888), contains an early summary of some of his theories that, in essence, claim that human progress is a function of individuality and imagination. It was a "colossal, stunning, godlike book," according to writer Lafcadio Hearn. He and his assistant Wrexie Leonard, Jr., left an unpublished manuscript of a book entitled Peaks and Plateaux in the Effect on Tree Life at his death.

In 1892, Lowell was named a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1893, he returned to the United States. After reading Camille Flammarion's La planet Mars, he was determined to study Mars and astronomy as a full-time job. He was particularly interested in Mars' canals, as illustrated by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who was director of the Milan Observatory. After learning that Schiaparelli began to notice decreased eyesight, Boston geologist George Russel Agassiz said that Lowell made the decision to start his observations. Lowell dedicated himself to the study of astronomy from 1893–94, establishing the observatory that bears his name. Flagstaff, Arizona Territory, was chosen as the home of his new observatory by the astronomy pioneer. Flagstaff, at an altitude of over 2,100 feet (6,900 feet), had few cloudy nights, and far from city lights, making it an excellent spot for astronomical observations. This was the first time an observatory had been deliberately located in a remote, elevated position for optimal viewing, with improved image quality, sharpness, and stability among other things. Lowell's Flagstaff observatory preferred smaller telescopes over larger ones, claiming that they were often better for viewing fine planetary details. William Pickering, another observer of Mars who had noticed the lines seen by Schiaparelli as well, helped in the establishment of his observatory.

Lowell received the Prix Jules Janssen in 1904, the highest award of the French astronomical society, Société astronomique de France. The focal points of his life were 23 years of his life, astronomy, Lowell Observatory, and others' work at his observatory.

Lowell, a devoted pacifist, was very sad to lose his life during the World War I was deeply saddened. His wellbeing was jeopardized as a result of a stroke on November 12, 1916, aged 61, along with other setbacks in his astronomical work (described below). Lowell is buried on Mars Hill near his observatory. Lowell said he wanted to "stick to the church," but at least one current author identifies him as an agnostic.

Lowell spent fifteen years (1893 to about 1908) on Mars, drawing intricate representations of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell's books include Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908). Lowell referred to the long-held belief that these markings indicated that Mars had evolved intelligent life forms with these writings.

His books include a comprehensive account of the planet's surface, as well as single and double figures; the "oases," as he referred to the dark spots at their intersections; and the inconsistent appearance of both, partly dependent on the Martian seasons. He claimed that an advanced but struggling race had adapted the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on a drier planet.

Although this theory piqued the interest of the general public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers were unable to see these marks, and few believed that they were as wide as Lowell claimed. Lowell and his observatory were largely ignored as a result. Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist that might account for these markings, the sixty-inch Mount Wilson Observatory telescope in Southern California in 1909 permitted closer inspection of the structures Lowell described as canals and revealed irregular geological features, most likely as a result of natural erosion.

By NASA's Mariner missions, the existence of canal-like features was definitively denied in the 1960s. The Mariner 4, 6, 7, as well as the Mariner 9 orbiter (1972), did not capture canals, but instead revealed a cratered Martian surface. The surface markings that appear to be canals are now considered an optical illusion. Matthew J. Sharps argues that Lowell and others' perception of the canals may have been influenced by a combination of psychosocial, Gestalt reconfiguration, and sociocognitive factors.

Although Lowell was best known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet Venus. In mid-1896, he began to observe Venus in detail, shortly after the 61-centimeter (24-inch) Alvan Clark & Sons refracting telescope was installed at his new Flagstaff, Arizona observatory. Lowell noticed the planet in the daytime sky with the telescope's lens reduced to 3 inches in diameter to minimize the hazy daytime atmosphere. According to what was believed then (and now): that Venus has no surface features visible from Earth because it is completely covered in a dusty atmosphere, Lowell observed spoke-like surface features including a central dark spot. In a 2003 Journal for the History of Astronomy paper and an article published in Sky and Telescope that year, Lowell's lowering of the telescope made it into a major ophthalmoscope, giving Lowell a glimpse of the shadows of blood vessels cast on the retina of his own eye.

Lowell's greatest contribution to planetary studies came during the last decade of his life, when he devoted himself to the quest for Planet X, a hypothetical planet outside of Neptune. By the weight of the planets' gravity, Lowell estimated that Uranus and Neptune were displaced from their predicted positions by their gravity. To determine predicted regions for the new planet, a team of human computers led by Elizabeth Williams was sent. In aperture, the program used a 5 inch (13 cm) camera. The instrument's small field of view of the 42-inch (110 cm) reflecting telescope made it impractical for searching. A 9-inch (23 cm) telescope on loan from Sproul Observatory was used by Lowell to find Pluto, but later Lowell Observatory (observatory code 690) photographed Pluto in March and April 1915, unaware that it was not a star at the time.

Clyde Tombaugh, a researcher at the Lowell Observatory, discovered Pluto near the location predicted for Planet X in 1930. Parts of Lowell's efforts, a stylized P-L monogram () – the first two letters of the new planet's name and also Lowell's initials – was selected as Pluto's astronomical symbol. However, it would later become clear that the Planet X theory was wrong.

Pluto's mass could not be determined until 1978, when its satellite Charon was discovered. This confirmed what had been increasingly suspected: Pluto's gravitational clout on Uranus and Neptune is negligible, but it is not nearly enough to account for the discrepancies in their orbits. The International Astronomical Union reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet in 2006.

In addition, it is now known that the discrepancies between Uranus and Neptune's predicted and observed positions were not caused by an unknown planet's gravity. Rather, they were due to an incorrect estimate for the mass of Neptune. Voyager 2's 1989 encounter with Neptune gave a more accurate estimate of the house's mass, but discrepancies disappeared when using this number.