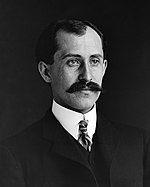

Orville Wright

Orville Wright was born in Dayton, Ohio, United States on August 19th, 1871 and is the Inventor. At the age of 76, Orville Wright biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 76 years old, Orville Wright physical status not available right now. We will update Orville Wright's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

The Wright brothers – Orville, 1871 – January 30, 1948 – Wilbur (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912) were two American aviation pioneers who were credited with inventing, building, and flying the world's first successful plane.

On December 17, 1903, 4 km (6 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, they conducted the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft with the Wright Flyer.

The brothers converted their flying machine into the first practical fixed-wing aircraft, the Wright Flyer III, in 1904-05.

Although they were not the first to build experimental aircraft, the Wright brothers were among the first to invent aircraft controls that made fixed-wing powered flights possible. The brothers' breakthrough was the development of a three-axis control system, which enabled the pilot to control the plane efficiently and maintains equilibrium.

On fixed-wing aircraft of all sorts, this technique is still common.

The Wright brothers concentrated on providing a reliable method of pilot monitoring right from the start of their aeronautical careers as the key to solving "the flying problem."

This approach was markedly different from other experimenters of the time, who primarily focused on creating efficient engines.

The Wrights also obtained more accurate data than ever before, enabling them to produce more effective wings and propellers thanks to a tiny home-built wind tunnel.

Their first U.S. patent did not demonstrate the development of a flying machine, but rather a system of aerodynamic control that modified a flying machine's surfaces.

Their participation with bicycles in particular influenced their belief that an unstable tool like a flying machine could be controlled and balanced with practice.

They carried out extensive glider experiments that also developed their pilot skills from 1900 to 1903, which culminated in their first powered flights in late 1903.

Charlie Taylor, a retail store employee, joined the team in designing their first aircraft engine in close cooperation with the brothers. Different groups have challenged the Wright brothers' status as the airplane's designers.

Much controversies regarding early aviators' claims are still in play.

Edward Roach, historian for the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, claims that they were knowledgeable self-taught engineers who could operate a small company, but that they did not have the necessary technology or temperament to dominate the burgeoning aviation industry.

Early career and research

Both brothers attended high school but did not receive diplomas. Wilbur's diploma was not released after finishing four years of high school after his family's sudden transfer from Richmond, Indiana, in 1884. On April 16, 1994, Wilbur's posthumously awarding of the diploma on his 127th birthday.

Wilbur was struck in the chest by a hockey stick while playing an ice-skating game with friends in late 1885 or early 1886, resulting in the loss of his front teeth. He had been healthy and athletic up to that point, but although his injuries didn't appear to be serious, he was forced to return. He had intended to attend Yale. Rather, he spent the next few years mainly housebound. During this period, he cared for his mother, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis, and aided his father in times of turmoil within the Brethren Church. 164 However, he also expressed dissatisfaction with his own lack of ambition.: 130

Orville dropped out of high school after his junior year to start a printing company in 1889, designing and building his own printing press with Wilbur's assistance. Wilbur joined the print shop and the West Side News became a weekly newspaper in March. On the masthead, Orville was listed as the publisher and Wilbur as editor. They converted the newspaper from a daily to an Evening Item in April 1890, but it only lasted for four months. They then concentrated on commercial printing. Orville's acquaintance and classmate, Paul Laurence Dunbar, who rose to international prominence as a ground-breaking African-American poet and writer. The Dayton Tattler, Dunbar's weekly newspaper, was published for a brief period by the Wrights.

In December 1892, the brothers opened the Wright Cycle Exchange, later the Wright Cycle Company, and started manufacturing their own brand in 1896, capitalizing on the national bicycle craze (spurred by the invention of the safety bicycle and its significant benefits over the penny-farthing model). They used this platform to finance their increasing interest in flying. Newspaper or magazine papers, as well as photographs of Otto Lilienthal's spectacular glides in Germany in the early or mid-1890s.

There were three major aeronautical events in 1896. Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley successfully flew an unmanned steam-powered fixed-wing model aircraft in May. Octave Chanute, a Chicago engineer and aviation authority, brought together several men who rode through Lake Michigan's sand dunes in mid-year. Lilienthal was killed in the plunge of his glider in August. These events weighed on the brothers' minds, especially Lilienthal's death. Later, the Wright brothers cited his death as the point where they first became involved in flight research.

"Lilienthal was without doubt the greatest of the predecessors," Wilbur said, "the world owes a large debt to him." Wilbur wrote a letter in May 1899 to the Smithsonian Institution requesting details and publications about aeronautics. They began their mechanical aeronautical experiments that year, drawing on Sir George Cayley's, Chanute, Lilienthal, Leonardo da Vinci, and Langley's work.

The Wright brothers had a united front face in the public eye, receiving equally praised for their invention. Biographers note that Wilbur initiated the initiative in 1899–1900, putting "my" machine and "my" plans together before Orville became deeply involved when the first individual singular became the plural "we" and "our" were used. "It's impossible to imagine Orville, brilliant as he was," the author states, "supplencing the driving force that started their career and kept it going from back room of a store to capitalist, president, and kings." Will did this? From the beginning to the end, he was the leader.

Despite Lilienthal's death, the brothers adopted his tactic: to practice gliding in order to master the art of control before embarking on a motor-driven flight. Percy Pilcher's death in another hang gliding accident in October 1899 only strengthened their conviction that a safe method of pilot control was the key to a safe flight. They regarded control as the unsolved third component of "the flying problem" right at the start of their experiments. They believed that they had sufficient evidence of the other two subjects, wings and engines, that they already had.: 166

The Wright brothers' proposal differed dramatically from more experienced practitioners of the day, notably Ader, Maxim, and Langley, who all made robust airframes and were scheduled to take to the air without having any previous flying experience. Although complying with Lilienthal's theory of exercise, the Wrights found that changing their body weight would compromise his balance and control. They were determined to find something better.

Wilbur found that birds changed the angle of their wings to make their bodies roll right or left on account of observation. The brothers decided that this would also be a good way for a flying machine to turn – to "bank" or "lean" – as a bird – and that, in comparison to a bicycle rider, a flying machine would be very familiar. They wished this technique would allow them to recover after the wind tilted the machine to one side (lateral balance). They questioned how to create the same effect with man-made wings and then discovered wing-warping when Wilbur twisted a long inner tube box at the bicycle store.

Other aeronautical investigators thought the flight was not so different from surface locomotion, but that the surface would be elevated. They feared in terms of a ship's rudder for steering, but the flying machine remained essentially level in the air, as did a train or an automobile, or a ship at the surface. The idea of deliberately leaning or rolling to one side seemed to be either ineffective or inconsiderate of their thinking. 167–168 Some of these other investigators, including Langley and Chanute, were looking for a elusive solution to wind disturbances, but the pilot of a flying machine would not be able to respond quickly enough to wind disturbances to use mechanical controls effectively. On the other hand, the Wright brothers wanted the pilot to have complete control. 168–169 For this reason, their early designs made no compromises toward built-in stability (such as dihedral wings). They deliberately built their 1903 first powered flyer with anhedral (drooping) wings, which are inherently unstable but less vulnerable to damage by gusty cross winds.