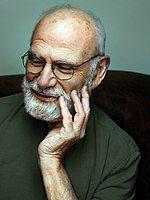

Oliver Sacks

Oliver Sacks was born in Willesden, England, United Kingdom on July 9th, 1933 and is the Non-Fiction Author. At the age of 82, Oliver Sacks biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 82 years old, Oliver Sacks physical status not available right now. We will update Oliver Sacks's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Oliver Wolf Sacks, (born in 1933) was a British neurologist, naturalist, scholar of science, and author.

Born in the United Kingdom and mainly educated there, he spent his time in the United States.

"The brain," he said, is the "most amazing thing in the universe." After Sacks obtained his medical degree from The Queen's College, Oxford, in 1960, he concentrated on writing best-selling case histories about both his patients' and his own experiences, as well as other literary works in the classical genre, with some of his books adapting for major playwrights, animated short films, opera, dance, fine art, and musical works in the classical style.

He later interned at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco and completed his residency in neurology and neuropathology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

He moved to New York in 1965, where he first studied at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in neurochemistry and neuropathology.

In 1966, he began working as a neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital's continuous-care facility in the Bronx, realizing that the neuro-research path he envisioned for himself would be a bad match.

Early life and education

Oliver Wolf Sacks was born in Cricklewood, London, England, as the youngest of four children born to Jewish parents, Samuel Sacks, a Lithuanian Jewish doctor (died June 1990), and Muriel Elsie Landau, one of England's first female surgeons (died 1972), was one of 18 siblings. Sacks' extended family of eminent scientists, physicians, and other notable figures, including director and writer Jonathan Lynn, the Israeli statesman Robert Aumann, and former Chief Rabbi Baron Sacks, Baron Sacks.

Michael Sacks and his older brother Michael were evacuated from London to avoid the Blitz in December 1939 and sent to a boarding school in the English Midlands, where he remained until 1943. Michael "... thrived on meager rations of turnips and beetroot and suffered cruel punishments at the hands of a sadistic headmaster," he and his brother Michael "remained tethering." Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood is the first autobiography in his book. He started returning home at the age of ten under Uncle Dave's tutelage, becoming an incredibly sharp amateur chemist. He later attended St Paul's School in London, where he formed lifelong friendships with Jonathan Miller and Eric Korn.

He expressed an ardent curiosity in biology with these individuals during childhood, and later shared his parents' ardent admiration for medicine. In 1951, he enrolled in Medicine at University and was accepted into The Queen's College, Oxford. The first half of Oxford's medical school is pre-clinical, and he earned a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in physiology and biology in 1956.

Although not compulsory, Sacks opted to continue doing research after being taken a course by Hugh Macdonald Sinclair. "I had been seduced by a series of vivid lectures on medicine and nutrition," Sacks says. "I was seduced by a series of lucid lectures on the history of medicine and nutrition... it was the origins of physiology, the theories, and personalities of physiologists, which came to life." Under Sinclair, Sacks was first introduced to the Laboratory of Human Nutrition at the school. Sacks' study was focusing on Jamaica ginger, a toxic and commonly used drug that has been shown to cause irreversible nerve damage. He was dissatisfied with Sinclair's lack of support and guidance after devoting months to study. Sacks wrote an account of his research findings but decided against doing so. "I felt myself sinking into a state of silence, but in some ways, agitated fear."

Seeing his poor emotional health, his tutor at Queen's and his parents recommended that he withdraw himself from academic study for a few years. His parents had then suggested that he spend the summer of 1955 on Israeli kibbutz Ein HaShofet, where physical activity would aid him. Sacks would later refer to his kibbutz experience as a "anodyne to the grueling months in Sinclair's lab." He said he shed 60 pounds (27 kg) from his previously obese body as a result of his vigorous, strenuous physical work he did there. He spent time in the region exploring the country with time spent scuba diving in Eilat, Spain's Red Sea port city, and began to rethink his future: "I wondered again, as I had wondered when I first arrived at Oxford if I really wanted to be a doctor." I had become keen on neurophysiology, but I also loved marine biology;... But I was 'cured' now; it was time to return to medicine, to resume clinical practice, and seeing patients in London.'

Sacks began his medical training at the University of Oxford and Middlesex Hospital Medical School in 1956. He took courses in medicine, surgery, orthopaedics, paediatrics, neurology, epidemiology, dermatology, infectious diseases, obstetrics, and several other fields over the next two-and-a-half years. He helped with a number of babies as a student. He earned his Bachelor of Medicine (BCh) degree in 1958 and, as per tradition, his BA was converted to a Master of Arts (MA Oxon) degree.

Sacks began his pre-registration house officer rotations at Middlesex Hospital the following month after completing his medical degree. "My eldest brother, Marcus, had studied at the Middlesex," he said, "and now I was following his footsteps." He said he first needed some hospital experience to boost his confidence before embarking on a St Albans hospital, where his mother worked as an emergency surgeon during the war. He then completed his first six-month service in Middlesex Hospital's medical unit, as well as another six months in the hospital's neurological unit. In June 1960, he completed his pre-registration year but was uncertain about his future.

Beginning life in North America

Sacks left the United Kingdom and travelled to Montreal, Canada, on July 9, 1960, his 27th birthday. He visited the Montreal Neurological Institute and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), informing them that he wished to be a pilot. They told him they would be the best in medical research after a series of interviews and checking his background. But his managers had second thoughts about him as he kept making mistakes, including missing data of several months of research, burning irreplaceable slides, and losing biological samples. "You are clearly gifted and we would love to have you," the head medical officer told him, "but I am not sure about your motives for joining." He was advised to fly for a few months and rethink. He traveled through Canada and the Canadian Rockies, which he referred to in his personal journal and later published as Canada: Pause, 1960.

He then migrated to the United States, finishing an internship at Mt. A residency neurology and neuropathology at UCLA are two of Zion Hospital in San Francisco. Sacks said he loved his wild imagination, tight control, and a seamless poetic style while visiting college. During a large portion of his UCLA experience, he lived in a rented house in Topanga Canyon and experimented with various recreational drugs. In a 2012 New Yorker essay and in his book Hallucinations, he referred to some of his experiences. He indulged in junk food throughout his youth in California and New York City:

After heading to New York City, an amphetamine-facilitated epiphany that began as he read a book by 19th century migraine doctor Edward Liveing inspired him to chronicle his experiences with neurological disorders and oddities, he became "Lives of Our Time." Despite the fact that he will remain a resident of the United States for the remainder of his life, he never became a citizen. In a 2005 interview, he told The Guardian, "I declared my intention to become a United States citizen in 1961," he said, but I never got around to it. I think it would be interesting to see that this was not just a long visit. I rather like the term'resident alien.' It's how I feel. I'm a sympathetic, local man, sort of visiting alien."

Personal life

Sacks never married and lived alone for the majority of his life. He refused to reveal personal information until later in his life. In his 2015 autobiography On the Move: A Life, he spoke about his homosexuality for the first time. He has been celibate for about 35 years since his forties, and Bill Hayes, a writer and columnist, has been an editor for the New York Times in 2008. Their friendship slowly developed into a long-term relationship that continued long after Sacks' death; Hayes wrote about it in his 2017 book Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me.

And How Are You, Dr. Lawrence Weschler's biography, And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? A colleague referred to Sacks as "deeply eccentric." Sacks' need to break taboos, like drinking blood mixed with milk, was explained by a friend from his days as a medical student, as well as how he used LSD and speed in the early 1960s. Sacks gave details about how he acquired his first orgasm while floating in a swimming pool and later when he was giving a man a massage. In a natural history museum he frequented often as a boy, he also admits to having "erotic fantasies of all sorts," many of which were related to animals, such as hippos in the mud.

In a 2001 interview, Sacks admitted that extreme anxiety, which he referred to as "a disease," had been a lifelong barrier to his personal relationships. His skepticism attributed to his prosopagnosia, a condition he studied in several of his patients, including the titular man from his book The Man Who Mistook His Hat. He had a physical disorder that delayed his development and even prevented him from seeing his own reflection in mirrors until he hit middle age.

Sacks swam almost every day of his life, beginning with his swimming-champion father's insistence on swimming as an infant. When he lived in the City Island section of the Bronx, he was particularly well-known for swimming, as he would routinely swim around the island or swim far away from the island and back.

Sacks was cousin of Nobel laureate Prof. Robert Aumann.

In 2006, Sacks underwent radiotherapy for a uveal melanoma in his right eye. In an essay and later in his book In an article and then in his book The Mind's Eye, he addressed his loss of stereoscopic vision as a result of the therapy, which resulted in right-eye blindness.

Metastases from the ocular tumour were discovered in his liver in January 2015. In a February 2015 New York Times op-ed column, Sacks revealed this development, estimating his remaining time in "months." He expressed his desire to "live in the richest, deepest, most cost-effective way I can." "I want and hope in the days that remain to deepen my friendships, to say goodbye to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the opportunity to travel to new levels of knowledge and wisdom," he said.

Sacks died of the disease at the age of 82 on August 30, 2015, surrounded by his closest friends.

Career

Sacks served as an educator and later clinical professor of neurology at Yeshiva University's Albert Einstein College of Medicine from 1966 to 2007, and he also held an appointment at the New York University School of Medicine from 1992 to 2007. He joined Columbia University Medical Center's faculty as a professor of neurology and psychiatry in July 2007. Recognizing the contribution of his work in bridging the arts and sciences, he was named Columbia University's first "Columbia University Artist" at the university's Morningside Heights campus at the University's Morningside Heights campus. He was also a visiting professor at the University of Warwick, the United Kingdom. In 2012, he returned to New York University School of Medicine as a professor of neurology and consulting neurologist in the school's epilepsy center.

Sacks' service at Beth Abraham Hospital contributed to the establishment of the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF); Sacks was an honorary medical advisor. In 2000, the Institute presented Sacks with its first Music Has Power Award. "His 40 years at Beth Abraham and the effect of music on the human brain and mind" were honoured in the IMNF's in 2006 to highlight "his 40 years at Beth Abraham" and recognize his "serious contributions in favour of music therapy and the influence of music on the human brain and spirit."

In New York City, Sacks operated a burgeoning hospital. Despite being in such demand for such consultations, he accepted a relatively small number of private patients. He served on the board of The Neuroscience Institute and the New York Botanical Garden.

Sacks first began to write about his experiences with some of his neurological patients in 1967. During an episode of self-doubt, Ward 23, Sacks' first published book, Ward 23, was ignited by him. His books have been translated into over 25 languages. In addition,, Sacks appeared in The New York Times, the New York Review of Books, The New York Times, London Review of Books, and scores of other medical, scientific, and general journals. In 2001, Lewis Thomas Award for Writing About Science was given to him.

Sacks' work has appeared in a "wide variety of publications than those of any other contemporary medical writer," and the New York Times announced in 1990 that he "has been a kind of poet laureate of contemporary medicine."

Sacks thought his literary style had evolved out of the nineteenth century "clinical anecdotes" literary style, which included elaborate case histories, which he described as novelistic. A. R. Luria, a Russian neuropsychologist who became a close friend through letters from 1973 to 1977, was also among his inspirations. After the debut of his first book Migraine in 1970, W. H. Auden's article encouraged Sacks to "be metaphorical, be mythical, be whatever you need."

Sacks delved into his cases with a wealth of narrative detail, focusing on the patient's experiences (in the case of his A Leg to Stand On, the patient was himself). Despite the fact that their medical disorders were normally incurable, the patients he described were often able to adapt to their situation in a variety of ways. His book Awakenings, based on the 1990 film Awakenings, discusses his experiences with the new drug levodopa at Beth Abraham Hospital, now Beth Abraham Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing, Allerton Ave, New York. Awakenings was also the subject of the first documentary film produced (in 1974) for the British television series Discovery. Tobias Picker, a composer and friend of Sacks, composed a ballet influenced by Awakenings for the Rambert Dance Company in Salford, England; Picker premiered an opera of Awakenings at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis in 2022.

He wrote about the aftermath of a near-fatal crash he suffered on his left leg while mountaineering alone above Hardangerfjord, Norway, a year after the publication of Awakenings.

He gives examples of Tourette syndrome and Parkinson's disease-related conditions in some of his other books. In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Michael Nyman's essay introduces a man with visual agnosia and was the subject of a 1986 opera. Temple Grandin, an autistic scholar, is the subject of his book's title, which received a Polk Award for magazine reporting. Parkinson's disease, as shown in the book's preface, can play a paradoxical role by bringing out latent powers, changes, evolution, and forms of life that may never be imagined or even be imaginable in their absence." Sacks' 1989 book Seeing Voices explores a variety of deaf research topics. At First Sight (1999), a romantic drama film based on An Anthropologist on Mars' essay "To See and Not See."

In his book The Island of the Colorblind Sacks, William Sacks chronicled an island where many people have achromatopsia (complete colorblindness, poor vision, and high photophobia). The Chamorro people of Guam have a high incidence of a neurodegenerative disease locally known as lytico-bodig disease (a devastating combination of ALS, dementia, and parkinsonism). Later, he and Paul Alan Cox published papers pointing to a possible cause of the disease, namely, toxin beta-methylamino L-alanine (BMAA) from the cycad nut that was accumulating by biomagnification in the flying fox bat.

Hallucinations, by Sacks in November 2012, was published. He investigated why ordinary people can occasionally experience hallucinations and challenged the stigma associated with the word. "Hallucinations don't refer directly to the insane," he said. They're becoming more popular in terms of sensory deprivation, intoxication, sickness, or injury. He also addresses the less common Charles Bonnet syndrome, which is often seen in people who have lost their eyesight. "Elegant... An absorbing plunge into a mystery of the mind," Entertainment Weekly described the novel as "elegant."

Sacks have been chastised in medical and disability studies groups. Arthur K. Shapiro, a Tourette syndrome researcher, said Sacks' work was "idiosyncratic" and relying too heavily on anecdotal evidence in his writings. Sacks' mathematical findings, according to researcher Makoto Yamachi, who wrote "In his analysis of the numerically gifted savant twins (in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), were irrelevant, and questioned Sacks' methods. Despite Sacks' reputation as a "compassionate" writer and doctor, some have felt that his victims were exploited. Sacks was dubbed "the man who mistook his patients for a literary career" by British academic and disability rights activist Tom Shakespeare, and one commentator called his work "a high-brow freak show." "I would hope that a reading of what I write shows respect and admiration, not the desire to reveal or display for the thrill, but it's a delicate industry."

He is also the author of The Mind's Eye, Oaxaca Journal, and On the Move: A Life (his second autobiography).

Sacks founded the Oliver Sacks Foundation, a non-profit group set up to increase knowledge of the brain by using narrative nonfiction and case histories, with the aim of releasing some of Sacks' unpublished books and making his extensive body of unpublished writings open for academic study before his death in 2015. In October 2017, his first posthumous book, River of Consciousness, an anthology of his essays, was published. The bulk of the essays had been published in previous periodicals or science-essay-anthology books and were no longer available. Prior to his death, Sacks established the order of his essays in River of Consciousness. Any of the essays examine repressed memories and other tricks by which the mind plays itself. It will be a collection of some of his letters that will be his next posthumous book. Sacks was a prolific handwritten letter correspondent, and he never interacted by email.