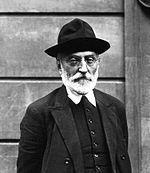

Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno was born in Bilbao, Basque Country, Spain on September 29th, 1864 and is the Poet. At the age of 72, Miguel de Unamuno biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 72 years old, Miguel de Unamuno physical status not available right now. We will update Miguel de Unamuno's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Unamuno's philosophy was not systematic but rather a negation of all systems and an affirmation of faith "in itself." He developed intellectually under the influence of rationalism and positivism, but during his youth he wrote articles that clearly show his sympathy for socialism and his great concern for the situation in which he found Spain at the time. An important concept for Unamuno was intrahistoria. He thought that history could best be understood by looking at the small histories of anonymous people, rather than by focusing on major events such as wars and political pacts. Some authors relativize the importance of intrahistoria in his thinking. Those authors say that more than a clear concept is an ambiguous metaphor. The term first appears in the essay En torno al casticismo (1895), but Unamuno leaves it soon.

In the late nineteenth century Unamuno suffered a religious crisis and left the positivist philosophy. Then, in the early twentieth century, he developed his own thinking influenced by existentialism. Life was tragic, according to Unamuno, because of the knowledge that we are to die. He explains much of human activity as an attempt to survive, in some form, after our death. Unamuno summarized his personal creed thus: "My religion is to seek for truth in life and for life in truth, even knowing that I shall not find them while I live." He said, "Among men of flesh and bone there have been typical examples of those who possess this tragic sense of life. I recall now Marcus Aurelius, St. Augustine, Pascal, Rousseau, René, Obermann, Thomson, Leopardi, Vigny, Lenau, Kleist, Amiel, Quental, Kierkegaard—men burdened with wisdom rather than with knowledge." He provides a stimulating discussion of the differences between faith and reason in his most famous work: Del sentimiento trágico de la vida (The Tragic Sense of Life, 1912).

A historically influential paperfolder from childhood to his last, difficult days, in several works Unamuno ironically expressed philosophical views of Platonism, scholasticism, positivism, and the "science vs religion" issue in terms of "origami" figures, notably the traditional Spanish pajarita. Since he was also a linguist (professor of Greek), he coined the word "cocotología" ("cocotology") to describe the art of paper folding. After the conclusion of Amor y pedagogía (Love and Pedagogy, 1902), he included in the volume, attributing it to one of the characters, "Notes for a Treatise on Cocotology" ("Apuntes para un tratado de cocotología").

Along with The Tragic Sense of Life, Unamuno's long-form essay La agonía del cristianismo (The Agony of Christianity, 1931) and his novella San Manuel Bueno, mártir (Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr, 1930) were all included on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

After his youthful sympathy for socialism ended, Unamuno gravitated towards liberalism. Unamuno's conception of liberalism, elaborated in essays such as La esencia del liberalismo in 1909, was one that sought to reconcile a great respect for individual freedom with a more interventionist state, bringing him to a position closer to social liberalism. In writing about the Church in 1932 during the second Spanish Republic, Unamuno urged the clergy to end their attacks on liberalism and instead embrace it as a way of rejuvenating the faith.

Unamuno was probably the best Spanish connoisseur of Portuguese culture, literature, and history of his time. He believed it was as important for a Spaniard to become familiar with the great names of Portuguese literature as with those of Catalan literature. He believed that Iberian countries should come together through the exchange of manifestations of the spirit but he was openly against any type of Iberian Federalism.

In the final analysis Unamuno's significance is that he was one of a number of notable interwar intellectuals, along with Julien Benda, Karl Jaspers, Johan Huizinga, and José Ortega y Gasset, who resisted the intrusion of ideology into Western intellectual life.

For Unamuno, the art of poetry was a way of expressing spiritual problems. His themes were the same in his poetry as in his other fiction: spiritual anguish, the pain provoked by the silence of God, time and death.

Unamuno was always attracted to traditional meters and, though his early poems did not rhyme, he subsequently turned to rhyme in his later works.

Among his outstanding works of poetry are:

Unamuno's dramatic production presents a philosophical progression.

Questions such as individual spirituality, faith as a "vital lie", and the problem of a double personality were at the center of La esfinge (The Sphinx) (1898), and La verdad (Truth), (1899).

In 1934, he wrote El hermano Juan o El mundo es teatro (Brother Juan or The World is a Theatre).

Unamuno's theatre is schematic; he did away with artifice and focused only on the conflicts and passions that affect the characters. This austerity was influenced by classical Greek theatre. What mattered to him was the presentation of the drama going on inside of the characters, because he understood the novel as a way of gaining knowledge about life.

By symbolizing passion and creating a theatre austere both in word and presentation, Unamuno's theatre opened the way for the renaissance of Spanish theatre undertaken by Ramón del Valle-Inclán, Azorín, and Federico García Lorca.