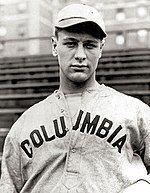

Lou Gehrig

Lou Gehrig was born in Manhattan, New York, United States on June 19th, 1903 and is the Baseball Player. At the age of 37, Lou Gehrig biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 37 years old, Lou Gehrig physical status not available right now. We will update Lou Gehrig's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Major league career

Gehrig made his major-league debut as a pinch hitter on June 15, 1923, while the New York Yankees midway through the 1923 season. He was mired in Yankee stalwart Wally Pipp at first base, a two-time AL home run champion and one of baseball's top power hitters in the Deadball era. Despite being a hitter in only 23 games and being left off the Yankees' 1923 World Series roster in 1923 and.500 in 1924, Gehrig saw little playing time, mainly as a pinch hitter, and was left off the 1923 World Series roster). He batted.295, the most popular Pipp in 1925, with 20 home runs and 68 runs batted in (RBIs) over 126 games.

Gehrig, unlike Ruth, was not a gifted position player, so he played first base, often in a position for a strong hitter but a poorer fielder. The 23-year-old Yankee's breakout season came in 1926, when he batted.313 with 47 doubles, 16 home runs, and 112 RBIs. Gehrig batted.348 with two doubles and four RBIs against the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1926 World Series. The Cardinals won the series of four games to three.

Gehrig had one of the best seasons by any batter in history in 1927, hitting.373 singles, 52 doubles, 18 triples, 47 home runs, and a new record 175 RBIs (surpassing teammate Babe Ruth's 171 years ago) with a.474 on-base percentage and a.765 slugging percentage. Babe Ruth's 117 extra-base hits in 1921, his 447 total bases, his second all-time, after Babe Ruth's 457 total bases in 1921 and Rogers Hornsby's 450 in 1922. Gehrig's performance in the World Series helped the 1927 Yankees reach a 110–44 record, the AL pennant (by 19 games), and a four-game victory over the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Despite the fact that the AL celebrated his season by naming him league MVP, Gehrig's career was overshadowed by Babe Ruth's record-breaking 60 home runs and the 1927 Yankees' overall dominance, which was often regarded as having the best lineup of all time – the legendary "Murderers' Row." Ruth's fame was so prominent that Gehrig's ghostwritten syndicated newspaper column that year was dubbed "Following the Babe."

The New York Yankees debuted wearing numbers on their uniforms in 1929. Gehrig wore number 4 because he fell behind Babe Ruth, who batted third in the lineup.

When Gehrig took the first home runs in a game in 1932 against the Philadelphia Athletics, he became the first player in the 20th century to reach four home runs in a game. When Athletics center fielder Al Simmons made a leaping catch of another fly ball at the center-field fence, he barely escaped his fifth home run. "Well, Lou, no one can take today away from you," manager Joe McCarthy told him after the game. However, John McGraw announced his resignation on the same day as the New York Giants' 30 years. The next day, McGraw, not Gehrig, grabbed the main headlines in the sports sections.

Gehrig played in his 1,308th game against the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman's Park on August 17, 1933, snaping the longest game-played streak ever played by Everett Scott. Scott was in attendance as a Browns guest.

Gehrig lived with his parents until 1933, when he was 30 years old. His mother destroyed all of Gehrig's romances before he met Eleanor Twitchell (1904-1954) in 1932; they began dating in September and married in September. She was the niece of Chicago Parks Commissioner Frank Twitchell. Gehrig was able to remove his mother's power and recruited Christy Walsh, Ruth's sports agent; Walsh helped Gehrig become the first celebrity to wear Wheaties boxes.

Gehrig's 300th home run against the Washington Senators on April 30, 1934, the second player to reach the milestone after Ruth. Gehrig captured the American League Triple Crown in 1934, leading the league with 49 home runs, 166 RBIs, and a.363 batting average.

Time proclaimed Gehrig "the game's No. 1" in a 1936 World Series cover story about him and Carl Hubbell. "British pride in banning a baseball as far as possible," says 1 batsman, who "hurries to run around the bases as quickly as possible."

Gehrig hired Babe Ruth's agent, who, in turn, advised him not to audition for the role of Tarzan in the independent film Revenge. Gehrig came only as far, as he posed for a widely distributed, and embarrassing, picture of him sporting a leopard-spotted costume. "I want to congratulate you for being a good first baseman" when Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs discovered the team. Sol Lesser, a British decathlon gold medalist who was unimpressed with Gehrig's legs, called them "more useful than decorative," and fired him on him.

Gehrig inserted himself as a pinch hitter in the game on June 1, 1925, swapping for shortstop Paul "Pee Wee" Wanninger. Manager Miller Huggins began Gehrig on day 2 in place of regular first baseman Wally Pipp, who suffered from a headache. Pipp, Aaron Ward, and Wally Schang were all in a slump, so Huggins made several lineup changes in an attempt to improve their results. Gehrig had played 2,130 games in a row, beating the previous record of 1,307 by a margin.

Gehrig was dubbed "the Iron Horse" by sportswriters in 1931. Gehrig was able to maintain his streak through pinch-hitting appearances and fortuitous timing in a few cases; in others, the streak continued despite injuries.For example:

In addition, x-rays that were late in his life revealed that Gehrig had suffered several fractures during his playing career, but he kept in the lineup despite those previously unveiled injuries. However, the streak was helped by Yankee general manager Ed Barrow's decision to postpone a game as a result of a rain out on a day when Gehrig was sick with the flu, though not raining.

He was also advised by his wife, Eleanor, not to end the streak of 1,999 games by being sick, but he was already down to 1,999 games and had already a 7-game lead over the previous record.

Gehrig's streak of 2,130 consecutive games lasted for 56 years before Baltimore Orioles shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. surpassed it on September 6, 1995; Ripken Jr. finished with 2,632 games in a row.

Although his result in the second half of the 1938 season was marginally better than in the first half, Gehrig reported physical changes at the midway point. "I was drained mid-season," he said at the end of the season. I'm not sure why, but I couldn't get it going again." Despite the fact that his final 1938 stats were above average (.295 batting average, 170 runs,.523 slugging percentage, 689 plate appearances, and 29 home runs), they were significantly down from his 1937 debut in which he batted.351 and slugged.643. He had four hits in 14 at-bats in the 1938 World Series, all singles.

Gehrig no longer had his once-formidable strength when the Yankees began their 1939 spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. Even his base running was affected, and he died at Al Lang Stadium at one point, before the Yankees' spring training park. He had not hit a home run by the end of spring training. Gehrig was praised as a good base runner early in his career, but as the 1939 season began, his coordination and speed had deteriorated dramatically.

With one RBI and a.143 batting average, he had his worst showing of his career by the end of April. Fans and the media also speculated about Gehrig's sudden demise. In one article, James Kahn, a reporter who wrote often about Gehrig, said: 'In one column':

He was certainly playing the ball, with just one strike out in 28 at-bats, but he was hitless in five of the first eight games. Joe McCarthy, on the other hand, found himself under pressure from Yankee management to shift Gehrig to a part-time job. Gehrig was unable to make a routine put-out at first base, bringing the whole situation to a halt. Johnny Murphy, the pitcher, had to wait for him to come over to the bag before attempting to field the ball. "Nice play, Lou," Murphy said. Gehrig's later appraisal was dismissive. "It was the simplest thing you could ever do in baseball, and I knew it was wrong with me at the time."

Gehrig was unconstitutionally wounded against the Washington Senators on April 30, when he was untouched. He was playing his 2,130th major league game.

Gehrig approached McCarthy before the game against the Tigers on May 2, the next game after a day off, and told the Yankees' skipper that he was doing so "for the good of the team." McCarthy complied, throwing Ellsworth "Babe" Dahlgren in first base, and also stated that if Gehrig felt he should play again, the position was his. Gehrig, the Yankee captain, handed over the lineup card to the stunned umpires ahead of the game, snapping the 14-year streak. "Ladies and gentlemen, this is the first time Lou Gehrig's name will not appear on the Yankee roster in 2,130 games," the Briggs Stadium announcer told the fans. When Gehrig sat on the bench with tears in his eyes, the Detroit Tigers' fans gave him a standing ovation. Wally Pipp, whom Gehrig had replaced at first base 2,130 games previously, was among those watching the game. In the nation's newspapers, a wire-service photo of Gehrig reclining against the dugout steps with a stoic expression appeared the next day. He stayed with the Yankees as team captain for the remainder of the season, but never played in a major-league game again.

Eleanor Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, as Gehrig's debilitation progressed. Her call was transferred to Charles William Mayo, who had been following Gehrig's career and his unethical absence of vitality. Mayo advised Eleanor that Gehrig should be sent as soon as possible.

Gehrig came from Chicago, where the Yankees were playing at the time, and he and the Yankees were unable to reach Rochester, and the Mayo Clinic opened on June 13, 1939. Doctors reported the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) on June 19, 1939, Gehrig's 36th birthday, after six days of extensive testing at the clinic. The prognosis was grim: slowly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years, but no impairment of mental functions would occur. Eleanor Gehrig was told that ALS was unknown but that it was painless, not contagious, and cruel; the central nervous system's motor functions are destroyed, but the mind remains fully aware until the end. Gehrig used to write letters to Eleanor, and one such note was published shortly after the diagnosis: Parts: Gehrig often wrote letters to Eleanor, and Parts of the disease.

Following Gehrig's return to the Mayo Clinic, he briefly rejoined the Yankees in Washington, D.C., as his train pulled into Union Station, greeted him with a group of Boy Scouts who were happily waving and wishing him good luck. Gehrig sank back, but he legged forward to his companion, Rutherford "Rud" Rennie of the New York Herald Tribune, who said, "They're wishing me luck — and I'm dying."

Although Gehrig's signs were consistent with ALS and that he did not experience the explosive mood swings and eruptions of uncontrolled violence that characterize chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), an article in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology's September 2010 issue discussed CTE as a result of repeated concussions and other brain injury. In 2012, Minnesota state representative Phyllis Kahn attempted to amend the legislation defending Gehrig's medical information in the hopes of determining if a correlation existed between his illness and his concussion-related injuries, including several instances in which he lost consciousness). He suffered with these injuries.

Gehrig played before the invention of batting helmets. To determine CTE, one would need autopsy results; none was done on Gehrig before his remains were cremated following his open-casket burial. Multiple physicians have claimed that reviewing records alone would be fruitless.

On June 19, 1939, the Mayo Clinic doctors announced their ALS diagnosis to the public. Gehrig's retirement was announced by the New York Yankees two days later, with a public push to honor him. Bill Hirsch, a sports columnist who wrote of the concept in his column, reportedly started the notion of an appreciation day. Other sportswriters were keen on the theory and promoted it in their respective journals. Some suggested that the appreciation day be held during the All-Star Game, but Yankees president Ed Barrow dismissed the suggestion straight away. Gehrig did not want him to be matched with any other all-star in the world. Barrow, who felt that the theory was valid and should be brought to fruition, wanted the appreciation day to be held soon, and the Yankees announced on Tuesday, July 4, 1939 "Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day" at Yankee Stadium, implying that the belief was valid and should be brought to fruition. The poignant ceremonies took place on the diamond during the Independence Day doubleheader against the Washington Senators. The ceremony was "perhaps as vivid and dramatic a pageant as ever was enacted on a baseball field," according to the New York Times' coverage the day after [as] 61,808 fans thundered a hail and farewell. The dignitaries and members of the Murderers' Row lineup attended the funerals and praised Gehrig. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York called Gehrig the "ideal model of the highest sportsmanship and citizenship" and Postmaster General James Farley concluded his address by saying, "Your name will live long in baseball, and wherever the game is played, it will bring pride and admiration to your record."

Joe McCarthy, the Yankees' manager, spoke to Gehrig, a close friend. McCarthy characterized Gehrig as "the finest example of a ballplayer, sportsman, and citizen that baseball has ever known." "Lou, what else can I say except that it was a sad day in the life of everybody who knew you when you walked into my hotel room that day in Detroit and told me you were leaving as a ballplayer because you felt yourself a hindrance to the team." You were never that bad, my God.

Gehrig's uniform number 4 was retired by the Yankees, making him the first player to be credited with the award in Major League Baseball. Many gifts, commemorative plaques, and trophies were given to Gehrig. Some of the VIPs were introduced by VIPs, while others were provided by the stadium's groundskeepers and janitorial workers. As Gehrig was given the gifts, he'd straight lay them on the ground as he no longer had the arm strength to hold them. The Yankees gave him a silver trophy with all of their engraved signatures on it. On the front, a poem by New York Times writer John Kieran was inscribed at the players' request.The inscription read:

The trophy became one of Gehrig's most coveted possessions. It is currently on view at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Gehrig gave "baseball's Gettysburg Address" to a sold-out audience at Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939. Gehrig did not want to speak out, but the audience booed him, and he had memorized some sentences ahead.

Only four sentences of the speech are recorded; complete versions of the speech are assembled from newspaper accounts.

For almost two minutes, the audience erupted and applauded. Gehrig stepped back from the microphone and wiped the tears away from his face with his handkerchief, clearly shaken. As a band performed "I Love You Truly," the audience erupted, "We love you, Lou." The moment was "one of the most touching scenes on a ball field ever witnessed" by the New York Times, causing even hard-boiled reporters to "swallow hard."