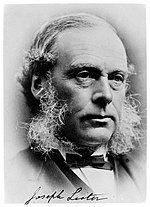

Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister was born in Upton House, Newham, England, United Kingdom on April 5th, 1827 and is the Doctor. At the age of 84, Joseph Lister biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 84 years old, Joseph Lister physical status not available right now. We will update Joseph Lister's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Sir Joseph Lister, Bt., a British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery, Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912), known as Sir Joseph Lister, Bt., was a British surgeon and a narrator of antiseptic surgery from 1883 to 1912. When working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Lister advocated for sterile surgery.

Lister has been able to sterilise surgical instruments and clean wounds by using carbolic acid, now known as phenol. Lister, a microbiologicist, advocated the use of carbolic acid as an antiseptic, so that it became the first commonly used antiseptic in surgery, utilizing Louis Pasteur's advances in microbiology.

He first thought it would be a good disinfectant because it was used to remove the stench from fields that had been irrigated with sewage waste.

He thought it was safe because fields treated with carbolic acid had no apparent ill-effects on the cattle that later grazed on them. Lister's work resulted in a decrease in post-operative infections and made surgical procedures more accessible to patients, earning him the title of "the father of modern surgery."

Early life

Lister was born in the village of Upton, West Ham, Essex, but now in London, England. He was the fourth son and third daughter of four sons and three daughters born to gentleman scientist Joseph Jackson Lister and Isabella Lister née Harris, who were married in Ackworth, West Yorkshire, on July 14th.

Thomas Lister, the last of several generations of farmers who lived in Bingley, West Yorkshire, was the paternal great-grandfather of Lister. As a young man, Lister joined the Society of Friends and passed his faith on to his son, Joseph Lister. In 1720, he moved to London to open a tobacconist on Aldersgate Street in the City of London's City of London. John Lister (1737-1855), his son, was born in the city. In 1752, Lister's grandfather was apprenticed to Isaac Rogers, a watchmaker, who later sold Bell Alley, Lombard Street, from 1759 to 1766. He later took over his father's smoking empire, but renounced it in 1769 in favour of working at his father-in-law Stephen Jackson's company as a wine-merchant at No 28 Old Wine and Brandy Values, opposite Tokenhouse Yard.

His father was a pioneer in the development of achromatic object lenses for use in compound microscopes, and in the process, he found Aplanatic Foci, a microscope in which the image point of one lens coincided with the focal point of another. The best magnification lenses manufactured an oversight secondary aberration known as a coma, which hindered with normal use up until that time. It was described as a major development in the science of histology, which turned it into an autonomous science. Lister's work by 1832 had earned him a reputation that could have prompted him to be elected to the Royal Society. Isabella Harris, the youngest daughter of master mariner Anthony Harris, was the youngest daughter of his mother. Isabella worked at Ackworth School, a Quaker school for the homeless, helping her widowed mother, who was the school's superintendent.

Mary Lister (1820–1894), the eldest sister to Joseph Lister, was the eldest daughter of the couple. On August 21, 1851, she married Inn and the Middle Temple barrister Rickman Godlee of Lincoln's Inn and the Middle Temple, who were guests at the friends' meeting house in Plaistow. The couple had six children. Rickman Godlee (1849–1925), a neurosurgeon who became Professor of Clinical Surgery at the University College Hospital, was their second child. Queen Victoria's surgeon and surgeon. In 1917, he became Lister's biographer. John Lister (1822-1896), Joseph and Isabella Lister's eldest son, died of a painful brain tumor, was the eldest son of Joseph and Isabella Lister. Joseph became the heir of the family following John's death. Isabella Sophia Lister (1823-1870), the couple's second daughter, married the Irish Quaker Thomas Pim in 1848, was the couple's second daughter. William Henry Lister (1828–1850), the brother of the Lister family, died after a long illness. Arthur Lister (1830–1908), a wine merchant, botanist, and lifelong Quaker who studied Mycetozoa, was the youngest son of the couple. He collaborated with his daughter Gulielma Lister to produce the standard monograph on Mycetozoa, and was given a Fellowship of the Royal Society. Jane Lister (1832–1920), a wholesale tea merchant, was married for the second time.

The Listers lived at 5 Tokenhouse Yard in central London for three years until 1822, where they operated a port wine company in collaboration with Thomas Barton Beck after their marriage. Beck, the grandfather of surgeon and proponent of the germ theory of disease, who would later promote Lister's findings in his fight to introduce antiseptics, was a man who would later champion Lister's discoveries. Lister's family immigrated to Stoke Newington in 1822. The family lived at the Upton House, a long low Queen Anne style home on 69 acres of land in 1826. It had been restored in 1731 to fit the period's style.

Education

Lister attended Benjamin Abbott's Isaac Brown Academy, a private Quaker academy in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, as a child. Lister was older when he attended Grove House School in Tottenham, which was also a private Quaker School to study mathematics, natural science, and languages. In the knowledge that he would study Latin at school, his father was adamant that Lister received a solid grounding in French and German. Lister's father was heavily urged from an early age. He became interested in natural history, which resulted in dissections of small animals, fish, and osteology that were found on his father's microscope and then drawn using the camera lucida method that his father had described to him or sketched. In Lister, his father's interest in microscopical research prompted him to become a surgeon and prepared him for a lifetime of scientific research.

When he was seventeen years old, Lister began attending school in the spring of 1844. Due to the religious tests that effectively barred him, he was unable to attend either University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge. So he applied to University College London Medical School, one of the few institutions in the United Kingdom that recognized Quakers at that time.

Although his father wanted him to continue his general education, the university had requested that every student obtain a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree before starting medical school. Lister began studying art for his BA. Lister was present at a celebrated surgery by Robert Liston, who performed a limb amputation on a patient who had been anaesthetised with the use of ether by Lister's classmate, William Squire.

Lister obtained a bachelor's degree in classical and botany in 1847. Lister was suffering from a mild case of smallpox while attending college, a year after his elder brother died of the disease. The bereavement, as well as the physical demands of his classes, culminated in a nervous breakdown. Lister decided to take a long break in Ireland to recuperate, but the university's medical studies have been delayed by more than a year.

Lister first registered as a medical student in October 1848. Lister served in the University Debating Society and the Hospital Medical Society during his undergraduate years.

He returned to college in the fall of 1849, with a gift of a microscope from his father.

John Lindley (1799–1865) professor of botany, Thomas Graham (1805–1865), Robert Edmond Grant (1793–1874) professor of comparative anatomy, and William Benjamin Carpenter (1813–1885) professor of medical jurisprudence. Although Lister often wrote about Lindley and Graham, it was Wharton Jones (1808–1891) professor of ophthalmic medicine and surgery and William Sharpey (1802–1880), who wielded the most influence on the Lister. Lister was captivated by Dr. Sharpey's lectures, which ignited in him a passion for experimental physiology and histology that never left him.

Thomas Henry Huxley lauded Wharton Jones for the method and quality of his physiology lectures. He was first in the number of scientific breakthroughs he made as a clinical scientist working in physiology. He was also known as a superb ophthalmic surgeon, who was also known as one of the field's top doctors. He conducted research into the blood and signs of inflammation that was carried out on the frog's web and the bat's wings, and no doubt that this strategy was recommended to Lister. Sharpey was the first to give a series of lectures on the subject. The field has been defined as part of anatomy long before that. Sharpey studied at Edinbugh University, then went to Paris to study medical and surgical surgery under Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin, the French anatomist. Sharpey met Syme and became lifelong friends in Paris. He taught anatomy with Allen Thomson as his physiological colleague after moving to Edinburgh. In order to become the first Professor of Physiology at University College, London, he left Edinburgh in 1836.

Lister had to complete two years of medical school before he could have obtained his degree. Walter Hayle Walshe (1812-1992), he began as an intern and then house physician. The Nature and Treatment of Cancer, a pathological pathology researcher and author of an 1846 study. In his second year in 1851, Lister became first a dresser in January 1851, then a house surgeon to John Eric Erichsen (1818–1896) in May 1851. Erichsen, a professor of surgery and author of the 1853 Science and Art of Surgery, was described as one of the most popular textbooks on surgery in the English language. Several editions were published, of which Marcus Beck edited the eighth and ninth editions, including Lister's antiseptic techniques and Robert Koch's germ theory. It was when Lister worked with Erichsen that he first became involved in wound healing.

Lister had only recently started serving as a dresser to Erichsen in January 1851, just as the male ward was suffering from an epidemic of erysipelas. An infected patient who came from an Islington workhouse was left in Erichsen's surgical ward for two hours. The hospital had been clean, but within days, there were 12 cases of infection and four deaths. Lister said that the disease was a form of surgical fever, and that new surgical patients were infected with the disease, but that older surgical patients with suppurating wounds survived'.

Lister was a patient advocate before he became a house surgeon. He came into contact with the various forms of blood-poisoning diseases, including pyaemia and hospital gangrene, a disease that rots living tissue with a remarkable speed. When reviewing the excision of a small boy's elbow during the autopsy, Lister noticed a thumerus bone at the seat of the humerus bone, which also affected the brachial and axillary veins. The pus travelled in the reverse direction along the veins, bypassing the vein valves. He also discovered suppuration in a knee-joint and multiple absces in the lungs. The lister knew that Charles-Emmanuel Sédillot had discovered multiple absces in the lungs caused by pus in the veins of an animal, but at the time, he was unable to explain the explanations but assumed the organs had a metastatic origin.

During his surgery, there was a rash of gangrene. The best way to get a recovery was to chloroform the patient, scrape of the soft slough off, and burn the necrotic flesh away with mercury pernitrate. Occasionally the therapy will be fruitful, but if a grey film appeared near the wound, it presages death. The therapy in one patient was repeated several times due to the patient's death, resulting in Erichsen amputating the leg, which healed fine. Lister's evidence revealed that the disease was a "local poison" and probably parasitic in origins. He inspected the diseased tissues under microscope. He discovered strange objects that he couldn't recognize because he had no idea how to draw conclusions from the observations.In his notebook he recorded:

Both Lister and Simpson wrote two papers on the epidemics, but both were lost. The first paper was about hospitalization, and the second was about the use of the Microscope. They were read to the University of Cambridge's Student Medical Society.

Ruth Richardson and orthopaedic surgeon Bryan Rhodes published a paper on June 26th, 2013 in which they discussed their discovery of Lister's first surgery, which they did not do while both researching their careers. Lister, a second-year medical student and working at a casualty ward in Gower Street, undertook his first operation at 1 p.m. on June 27th. Julia Sulivan, a mother of eight grown children, was the subject of the operation. She had been stabbed in the abdomen by her husband, a alcoholic and ne'er-do well-well who had been arrested. Lister was summoned as a witness in the Old Bailey's trial on September 15, 1851. His testimony vindicted the husband, who was taken to Australia for 20 years.

The woman had a coil of intestines about eight inches across, with two intestines that had been removed in two places, protruding from her lower abdomen, according to the lister. There were three open wounds in the abdomen. Lister was unable to bring them right back to the body after sanitizing the intestines with blood-warm water, so he decided to postpone the procedure. They were then put back in the body, the wounds sewn closed, and the abdomen sutured. To encourage the intestines to recover, the patient was given opium to induce constipation. Sulivan recovered her health. It was only a decade ago that the Glasgow Infirmary's first public service had been performed.

Historians had missed this operation. In his essay on Lister, Joseph Lister, and abdominal surgery, written in 1968, Liverpool consultant surgeon John Shepherd failed to mention the surgery, instead starting his dates from the 1960s onwards. He was apparently unaware of what Lister did.

While studying at university, Lister wrote his first paper, "Observations on the Iris' Contractile Tissue." It was considered worthy enough to be published in the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science in 1853.

Wharton Jones, a professor at the University College Hospital, presented Lister with a piece of a fresh human iris on August 11, 1852. Lister was present at Jones' surgery and had the opportunity to investigate the iris for the first time. Lister reviewed the existing research, as well as collecting six surgical specimens from patients who underwent a surgical procedure on their eye. Due to the pressure to pass his final exam, Lister was unable to complete the study to his delight.He offered an apology in the paper:

The paper advanced the research of Swiss physiologist Albert von Kölliker, revealing the presence of two distinct muscles in the iris, namely the dilator and sphincter, which corrected previous researchers' findings that there were no dilator pupillae muscle.

In the same journal, his next paper was an investigation into goose bumps. In comparison to other mammals in which large tactile hairs are associated with striated muscle, Lister was able to confirm Kölliker's experimental findings, demonstrating that in humans the smooth muscle fibres are responsible for the hair falling out from the skin. Lister demonstrated a new method of extracting histological sections from scalp tissue.

Lister's microscopy skills were so advanced that he was able to correct the findings of German histologist Friedrich Henle, who mistook small blood vessels for muscle fibres. He made camera lucida drawings that were so accurate that they could be used to scale and measure the observations in each of the papers.

Both papers attracted considerable attention both in the United Kingdom and abroad. Both papers were particularly enthralled by Richard Owen, a long friend of Lister's father. On August 2, 1853, Owen considered recruiting Lister for his own department and sent him a thank-you letter. Kölliker was particularly pleased with Lister's review. Kölliker, who had made many trips to the United Kingdom, would eventually visit Lister and became life-long friends. Rickman Godlee's letter to their close friends was referred to in a letter written by Kölliker on November 17th, which he chose to use to illustrate their relationship. Kölliker wrote to Lister, congratulating Lister on winning the Copley medal and remembering his time in Scotland with Syme and Lister. Kölliker was 80 years old at the time.

In the fall 1852, Lister received a Bachelor of Medicine degree with distinction. Lister received several prestigious awards during his last year, many of whom were fiercely contested among the London teaching hospitals' student population.He won the Longridge Prize

That included a £40 stipend. He was also awarded a gold medal in Structural and Physiological Botany. Lister earned two gold medals in Anatomy and Physiology as well as surgery, as well as a two-year Gold medal for his second attempt at medicine. Lister passed the exam for the Royal College of Surgeons in the same year, bringing the total number of years of education to a close.

Sharpey recommended that Lister spend a month in Edinburgh's medical clinic and then return to European universities for a longer period of study. Sharpey himself had been taught first in Edinburgh and then Paris. Sharpey was in Paris with Syme, a clinical surgery professor who was widely regarded as the best surgeon in the United Kingdom while visiting him. Sharpey and many other surgeons since 1818 had been sent north to Edinburgh, thanks to John Hunter's influence. Hunter had mentor Edward Jenner, who is best known as the first surgeon to take a scientific approach to medicine study, and he had a better understanding of healing than many of his colleagues. For example, his 1794 paper, A treatise on the blood, inflammation, and gun-shot wounds, was the first systematic study of swelling, finding that inflammation was common to all diseases. Surgery was transformed from a hobbyists or amateurs' occupation into a scientific occupation, thanks to Hunter. Surgeons who wanted to imitate those procedures moved north for education as the Scottish universities taught medicine and surgery from a scientific perspective. Several other features separated Scottish universities from the medical universities in the south. They were inexpensive and didn't require religious admissions exams, attracted the most literate students in the United Kingdom. Medical schools in Scotland had developed from a scholarly past, where English medical schools were dependent on hospitals and practices, which was the most significant distinguisher. There were no experts in English medical schools at the time, and although Edinburgh University's medical school was large and active at the time, southern medical schools were still struggling, with inadequate laboratory space and teaching materials. Surgery in England tend to be seen as manual labour rather than a respectable calling for a gentleman academic.

Later life

Lister attended the Sorbonne's 70th birthday of Pasteur, including ministers, ambassadors, President of France Sadi Carnot, and representatives of the Institut de France. Pasteur began the ceremony at 10.30 a.m. When he raised his hand, the lister, who had been invited to deliver the address, received a standing ovation. In his address, he spoke about the debt he and his surgery associates To Pasteur suffered with. Pasteur strode forward and kissed Lister on both cheeks in a scene that was later filmed by Jean-André Rixens. Lister was present in January 1896 when Pasteur's body was laid in his tomb at the Pasteur Institute.

Agnes Lister died of acute pneumonia in 1893, four days into their spring break in Rapallo, Italy. Lister's private practice, although still responsible for the wards of Kings College Hospital, has slowed alongside a fondness for experimental research. Social gatherings had been severely halted. He sank into religious melancholy while reading and writing lost his appeal, and he sank into religious melancholy. Lister was a professor at Kings College Hospital in 1895 and died on July 31. In a small display held in recognition of the admiration and admiration that his coworkers felt, Lister was presented with a portrait painted by Scottish artist John Henry Lorimer.

Despite recovering from a stroke, he came back to public view from time to time. He had served as a Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria for many years, and from March 1900 he was named Serjeant Surgeon to the Queen, making him the Queen's senior surgeon in the Royal Households of the sovereign. He was recalled as such by her successor, King Edward VII, after her death the year before.

Edward was operated on by Sir Frederick Treves two days before his scheduled coronation on June 24th, 1902, with a 10-day history of appendicitis with a distinct mass on the right lower quadrant. The appendectomy, which was originally intended for internal use, posed a significant risk of death by post-operative inflammation, and surgeons refused to operate without consulting Britain's top surgical authority. The King survived, promising them in the newest antiseptic surgical techniques (which they followed to the letter), but the King later told Lister, "I know that if it hadn't been for you and your work, I wouldn't be sitting here today."

Lister left London in 1903 to live in Walmer, a coastal village.

Lord Lister died on February 10, 1912 at his country's home at the age of 84. The first part of Lister's funeral took place at 1.30 p.m. on February 16, 1912. His body was moved from his house to The Chapel of St. Peter. By German Count Paul Wolff Metternich's on behalf of German Emperor Wilhelm II, Faith and a wreath of orchids and lilies was presented by the German ambassador. Frederick Bridge performed Henry Purcell's music, Chopin's funeral march, and Beethoven's Tres Aequili before the service began. The body was then placed on a high catafalque, where his Order of Merit, Prussian Pour le Mérite, and Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog were placed. It was then carried by several pallbearers, including John William Strutt, Archibald Primrose, Rupert Guinness, Robert Geikie, Watson Cheyne, Godlee, and Francis Mitchell Caird, where the catafalque was transferred to Hampstead Cemetery in London, where it was discovered at 4 p.m., with the catafalque residing there at 4 p.m. Lister's body was then buried in a plot in the south-east corner of his central chapel, attended by a select group of his relatives and acquaintances. In The Times on the day, many tributes from learned societies from around the world were published. On the same day, a memorial service was held in St Giles' Cathedral in Edinburgh. On February 15, 1912, Glasgow University held a memorial service in Bute Hall.

A marble medallion of Lister stands in Westminster Abbey's north transept, alongside four other well-known scientists, Darwin, Stokes, Adams, and Watt.