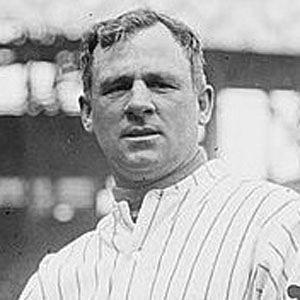

John McGraw

John McGraw was born in Truxton, New York, United States on April 7th, 1873 and is the Baseball Manager. At the age of 60, John McGraw biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 60 years old, John McGraw physical status not available right now. We will update John McGraw's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

In 1890, Kenney bought a portion of the new professional baseball franchise in Olean, New York. The team was to play in the newly formed New York–Pennsylvania League. In return for this investment, he was named Olean's player/manager, responsible for selecting and signing players. When approached by McGraw, Kenney doubted the boy's curveball would fool professional ballplayers. Persuaded by the assurance McGraw could play any position, Kenney signed him to a contract on April 1, 1890. McGraw would never return to live in Truxton, the place of his birth.

Olean was 200 miles (320 km) from Truxton, and this was the farthest the youngster had ever traveled from his hometown. He began the season on the bench. After two days, Kenney inserted him into the starting lineup at third base. McGraw later described his first professional game:

Seven more errors in nine more chances followed that day. Both the team and McGraw remained ineffective, and he was fired by Kenney after six games, though the captain gave him $70, equivalent to $2,111 in 2021, and wished him luck. He signed with a team in Wellsville, New York, who played in the Western New York League. The level of baseball played there was the lowest of the minor leagues, and McGraw still struggled with his fielding. But during the 24 games he appeared in for the club, he hit with a batting average of .365, a glimpse of his later hitting prowess.

After that first season, McGraw caught on with the offseason team of promoter Alfred Lawson. McGraw joined the team in Ocala, Florida, and the team sailed from Tampa to Havana, Cuba, where they played the local teams in what was then a Spanish colony. McGraw, who played shortstop, became a favorite of local fans, who dubbed him "el mono amarillo" (the yellow monkey), referring to his speed, his diminutive size, and the color of his team's uniforms. McGraw fell in love with Cuba and returned there many times in later years.

Lawson took his team to Gainesville, Florida, in February 1891, and persuaded the National League Cleveland Spiders to play his team. McGraw hit three doubles in five times at bat, playing errorless ball at shortstop, and the reports of that game led several minor league teams to seek to sign him. Lawson acted as the boy's agent, and advised him to request $125 monthly and a $75 advance. The manager of the Cedar Rapids club in the Illinois–Iowa League was the first to wire the money, and McGraw signed with them. Other teams claimed that McGraw had also taken advance money from them (though McGraw maintained he returned it) and one even threatened legal action. This came to nothing, allowing McGraw to play with Cedar Rapids.

By August, the league had financial woes but McGraw was hitting .275 and had become known as a tough shortstop. Billy Barnie, manager of the American Association's Baltimore Orioles, had heard about McGraw, and wrote to the Rockford team's Bill Gleason, a former Oriole, for a recommendation, which according to McGraw biographer Charles C. Alexander must have been favorable, as Barnie then wired Hank Smith, another former Oriole who was playing for Cedar Rapids, asking if there was any chance Baltimore could acquire McGraw. Cedar Rapids agreed to give McGraw his release, and he left by rail for Baltimore. McGraw arrived at Camden Station in Baltimore on August 24, 1891, still only 18 years old, but now a major-league baseball player. McGraw described his new home upon his arrival as "a dirty, dreary, ramshackle sort of place." Barnie was unimpressed by the short stature of the player he had recruited unseen, but McGraw assured him, "I'm bigger than I look."

During the short part of the 1891 season McGraw was with the Orioles, he hit .245. Initially he played shortstop, but his poor fielding (18 errors in 86 chances) caused Barnie, who quit before the end of the season, to try him at other positions. Despite his poor fielding percentage, McGraw was quickly signed to a contract for 1892 by club owner Harry Von der Horst. The American Association failed after the 1891 season, and the Orioles and other surviving franchises moved to an expanded twelve-team National League.

Early in the 1892 season, Von der Horst hired outfielder Ned Hanlon of the Pittsburgh Pirates to manage the Orioles. The Orioles lost over 100 games, finishing last by a wide margin. Of the seventeen players Hanlon inherited, he kept only three: pitcher Sadie McMahon, catcher Wilbert Robinson and McGraw. According to baseball author Burt Solomon, "Hanlon saw that McGraw's value to the Orioles came less from his agility than from his intensity. He never gave up and had contempt for anyone who did, John McGraw could drive his teammates to another level of play." But little of that showed in the 1892 season, in which McGraw hit .267 with 14 stolen bases while playing a variety of positions. During the 1892–93 offseason, McGraw attended Allegany College (soon to be renamed St. Bonaventure), trading his skills as a baseball coach for the right to attend without paying tuition.

In 1893, Hanlon secured Hughie Jennings from the Louisville Colonels, a shortstop whose acquisition caused Hanlon to displace McGraw from that position. The team finished eighth in 1893, while McGraw hit .327, second on the club to Robinson, and led the league in runs scored. He spent a second winter at St. Bonaventure, this time with Robinson as his assistant coach and fellow student. During the offseason, McGraw narrowly avoided being dealt to the woeful Washington Senators when a trade for Duke Farrell fell through. Deciding McGraw could handle third base, Hanlon traded two infielders for five-time batting champion Dan Brouthers and diminutive outfielder Willie Keeler.

The Orioles' 1894 spring training took place in Macon, Georgia, where Hanlon taught the players innovative plays that he had thought of during his playing career, and in the evening, drilled them on baseball's rules and possible ways of taking advantage of them. The innovations of the Orioles of the mid-1890s would include the Baltimore chop, hitting a pitched ball so it would bounce high and allow the batter to reach first base safely, and having the pitcher cover first base when the first baseman fielded a ball that took him away from the base, and though they probably did not invent the hit and run, they were the first team to employ it as a regular maneuver. McGraw often took the lead in the discussions. When the team played in New Orleans, a local sportswriter called him "a fine ball-player, yet he adopts every low and contemptible method that his erratic brain can conceive to win a play by a dirty trick". This included shoving, holding, and blocking baserunners, at a time when there was often only a single umpire. One baserunner, anticipating that McGraw would hold him by the belt, loosened it and when he broke for home, McGraw was left holding the belt in his hand as the runner scored.

McGraw usually batted leadoff for the 1894 Orioles, batting .340 and stealing 78 bases, second in the league. He would foul off pitch after pitch—a valuable talent in the pre-1901 era in which foul balls generally did not count as strikes—and, with Keeler, "elevated into an art form" the hit and run. Many of the players, including McGraw, lived in the same Baltimore boarding house, and talked baseball deep into the night. From such discussions arose the discovery that a runner on third had an excellent chance of scoring if he left at the pitcher's first motion and the batter bunted, originating the squeeze play. A reputation for dirty play led to McGraw being dubbed "Muggsy", a nickname he strongly disliked, by The Washington Post. The Orioles won their first pennant, besting the New York Giants and the Boston Beaneaters. Amid disputes over money, they lost the postseason Temple Cup series to the second-place Giants. After a brief visit to Truxton, McGraw spent the winter at St. Bonaventure.

The Orioles' "Big Four" (McGraw, Jennings, Keeler and Joe Kelley) held out to start 1895, but came to terms with the club in time for spring training. By 1895, McGraw had become controversial for his aggressive style of play. Some writers urged Hanlon to rein him in, but others argued that fans were flocking to the ballpark to see such play. In spite of the controversy, the Orioles won their second consecutive pennant, though they lost the Temple Cup again, this time to the Spiders. McGraw, suffering from malaria, missed part of the season, but hit .369 in 96 games, with 61 stolen bases and 110 runs scored. McGraw again went to St. Bonaventure, returning to Baltimore when the fall term ended in mid-December.

During 1896 spring training, McGraw fell ill with typhoid fever in Atlanta. By the time he had convalesced, in late August, the Orioles had nearly secured their third straight pennant, this time winning the Temple Cup over the Spiders in four games. McGraw appeared in only 23 games for Baltimore, batting .325. After the season, the Orioles had planned an exhibition tour of Europe, but it was canceled over concerns poor weather would preclude too many games. The Big Four went anyway, as tourists, visiting Britain, Belgium and France. Following their return, in February 1897, McGraw married Minnie Doyle, whose father was a city official. McGraw and the Orioles both had seasons that disappointed them in 1897, McGraw hitting .325, and the team plagued by injuries as Baltimore lost the pennant to the Beaneaters, though the Orioles won the final iteration of the Temple Cup. In 1898, McGraw hit .342, but the Orioles finished second again, six games behind the Beaneaters.

The Orioles' success on the field had not translated to increased attendance, which fell substantially as the Orioles won pennants, as violence on the field spread into the stands. The Spanish–American War of 1898 distracted the public from baseball, causing financial problems for the teams. Before the 1899 season, Van der Horst and Hanlon (a co-owner) bought half the shares in the Dodgers, while Brooklyn owners, led by Charlie Ebbets, bought a 50 percent interest in the Orioles. Brooklyn drew better attendance than Baltimore, and under the arrangement, known as "syndicate baseball", manager Hanlon and the better Oriole players would move to Brooklyn. McGraw and Robinson, who had financial interests in Baltimore, refused to go and before the 1899 season, McGraw was made player/manager of the Orioles.

McGraw schooled his players in the Orioles system, and led by example, hitting .391 for the season. To Hanlon's surprise, attendance in Baltimore rebounded, and the Orioles remained close to Brooklyn in the pennant race through late August, when McGraw had to leave the team due to the illness of his wife. By the time he returned, after her death, Brooklyn had clinched the pennant; the Orioles finished fourth. Nevertheless, for getting the castoff Orioles to perform so well amid his personal tragedy, McGraw was hailed as a managerial genius in the newspapers.

Syndicate baseball was insufficient to revive the finances of the National League, and before the 1900 season, four NL teams (including Baltimore) were ended. McGraw and Robinson were sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. They did not report until the season had begun, having secured increases in salary and a concession that their contracts would not contain the then-standard reserve clause that bound them to the signing team for the following season. Thus, they would be free agents after the 1900 season. Injured for part of the season, McGraw hit .337 in 98 games as the Cardinals finished tied for fifth, but when manager Patsy Tebeau resigned in August, McGraw ruled out replacing him.

Ban Johnson, president of the minor league Western League, sought to build a second major league, which would seek to attract fans wanting baseball without rowdyism or aggression towards umpires. McGraw and Robinson, centerpieces of the old Orioles where such aggression was routine, were an odd fit, but as Johnson renamed his circuit the American League (AL) and sought to put franchises in abandoned NL cities like Baltimore, they became key to his plans. He was confident he could control them, since one of the requirements was that franchises grant the league an option to buy a majority stake and thus take them over if necessary.

Even while under contract to the Cardinals, McGraw and Robinson were involved in meetings aimed at upgrading the Western League to major league status, and on November 12, 1900, they signed an agreement with Johnson giving them exclusive rights to form an AL franchise in Baltimore, securing financial backing from local figures. McGraw spent much of the winter seeking to sign players. Among them was Charley Grant, an African-American second baseman who McGraw alleged was a Native American, but Charles Comiskey, owner of the AL Chicago White Sox, was undeceived, thus ending McGraw's only attempt to break the baseball color line—McGraw, like many of the time who grew up in the rural North, had no strong views about African Americans. Thereafter, McGraw kept a file on talented African-American ballplayers, seeking to be prepared if the major leagues integrated, which did not happen in his lifetime.

McGraw batted leadoff and managed the Orioles as Major League Baseball made its return to Baltimore in 1901, but missed games due to injuries and because of a suspension by Johnson for abusing the umpire. The Orioles finished fifth, McGraw batting .349 in 73 games. The team lost money. On January 8, 1902, McGraw married for the second time, to Blanche Sindall, whose father was a Baltimore housing contractor.