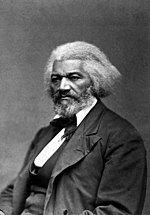

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was born in Talbot County, Maryland, United States on February 14th, 1818 and is the Autobiographer. At the age of 77, Frederick Douglass biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 77 years old, Frederick Douglass has this physical status:

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Wilson Bailey, c. 1818–1895) was an American social reformer, orator, poet, and statesman.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, earning acclaim for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings.

He was characterized by abolitionists as a living counter-example to slaveholders' claims that slaves lacked the cognitive ability to function as free American citizens in his time.

Douglass wrote several autobiographies at a time, and northerners of the time found it difficult to believe that such a great orator had once been a slave.

In his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, became a best-selling book, as well as his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Douglass, who served as a zealot, remained an active protester against slavery and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

It was first published in 1881 and updated in 1892, three years before his death, three years before his death, and covered events during and after the Civil War.

Douglass has also argued for women's suffrage and held numerous public offices.

Douglass was the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States by a black, female, Native American, or Chinese immigrant immigrants, without his permission.

He was also a believer in dialog and in building alliances across racial and ideological boundaries, as well as in the United States Constitution's liberal values.

"I would unite with anyone to do right and not do wrong," Douglass' willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, under the slogan "No Union with Slaveholders."

Life as a slave

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland. The plantation took place between Hillsboro and Cordova; his grandfather's cabin was most likely located east of Tappers Corner and west of Tuckahoe Creek. Douglass wrote his first autobiography, "I have no concrete idea of my age, and I've never seen any credible record containing it." He gave more specific estimates of when he was born in subsequent autobiographies, his most recent estimate being 1817. Douglass was born in February 1818, according to historian Dickson J. Preston, who was based on the extant records of Douglass' former owner, Aaron Anthony. Despite the fact that his birthdate is unknown, he chose February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother called him her "Little Valentine" after his birth.

Douglass was of mixed race, with Native American and African on his mother's side as well as European. According to historian David W. Blight's book "However White" in Douglass' 2018 biography, he was "most definitely white." After escaping to the North in September 1838, Douglass claimed that he gave him the surname Douglass, having already dropped his two middle names.

He later told of his earliest days with his mother: he recalled the times with his mother.

After being estranged from his mother during infancy, young Frederick lived with his maternal grandmother Betsy Bailey, who was also a slave, and his maternal grandfather Isaac, who was free. Betsy would live until 1849. Frederick's mother lived on the plantation about 12 miles (19 km), but she died after visiting Frederick just a few times when he was 7 years old.

He was invited to speak "a colored school" in Talbot County, much later than 1883, about 1883.

Douglass was estranged from his grandparents and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony served as superintendent. Douglass was born in 1826 and was married to Lucretia Auld, Thomas Auld's wife, who sent him to Baltimore to serve Thomas Auld and his wife Sophia Auld. Sophia saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and dressed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket from the day he arrived. Douglass described her as a kind and compassionate woman who treated him "as she felt one human being should treat another." Douglass said he was lucky to be in the city, where slaves were almost freemen, compared to slaves on plantations.

Sophia Auld began teaching Douglas Douglass the alphabet when he was around 12. Hugh Auld disapproved of tutoring, fearing that literacy would encourage slaves to want freedom. Douglass later referred to this as the "first definite antislavery lecture" he had ever seen. Douglass wrote, "Very well, thought I." "A child is unfit to be a slave." "I instinctively agreed to the plan, and from that moment, I knew the direct route from slavery to liberty."

Sophia came to believe that education and slavery were incompatible, so she took a newspaper away from Douglass for one day under her husband's influence. She stopped teaching him entirely and blocked all potential reading materials, including her Bible, from him. Douglass' autobiography recalled how he learned to read from white children in the neighborhood and studied the men with whom he worked.

Douglass continued to read and write, although it was disguised. "Knowledge is the transition from slavery to liberation," he said later. Douglass's new field of thought led him to question and condemn slavery as he began to read newspapers, pamphlets, political reports, and books of every description. Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, an anthology he found around age 12, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights. The book, first published in 1797, is a classroom reader, with essays, speeches, and dialogues to assist students in learning reading and grammar. He later learned that his mother had also been literate, which he would later reveal:

"When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he eventually had more than thirty male slaves on Sundays, and some even on weeknights in a Sabbath literacy academy."

Douglass was taken back from Hugh by Thomas Auld in 1833 ("[a]s a way of punishing Hugh," Douglass later explained). Douglass was sent by Thomas to work with Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave breaker." Douglass was whipped so often that his wounds took no time to heal. Douglass' frequent whippings tore his body, soul, and spirit, according to his later. The 16-year-old Douglass retaliated against the beatings but the Douglass fought back. Douglass never attempted to hurt him after he had won a physical confrontation.

Douglass, recounting his beatings at Covey's farm in Narrative of Frederick Douglass' Life, an American Slave, said himself as "a man turned into a brute." Douglass continued to see his physical fight with Covey as life-changing, and he told the tale as follows: "You've seen how a man was made a slave; you'll see how a slave was made a man."

Family life

Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass Jr., Charles Remond Douglass Jr., and Annie Douglass died before they were five years old (died at the age of ten). His newspapers were mainly produced by Charles and Rosetta.

Anna Douglass remained a devoted promoter of her husband's public service. Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, two people with whom he worked, caused continuing rumors and scandals. Assing was a journalist who first came from Germany and saw My Bondage and My Freedom in German. She stayed at his house "for many months at a time" as his "intellectual and emotional companion" until 1872.

Anna Douglass was held "in complete contempt" by the dismissal of her husband, and she was adamantly hoping that Douglass would separate from his wife. Assing and Douglass "were definitely lovers," Douglass biographer David W. Blight concludes. Although Douglass and Assing are widely believed to have had an intimate friendship, the remaining correspondence shows there is no evidence of such a relationship.

Anna died in 1882, but Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the niece of Douglass's daughter, Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague and a friend. Pitts, a graduate of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, worked on Alpha, a liberationist journal based in Washington, D.C., where she later served as Douglass' secretary.

After learning of the marriage, Assing, who suffered with depression and was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer, committed suicide in France in 1884. Assing's death, Assing bequeathed Douglass, a "large album" and his collection of books from her library.

Pitts' marriage of Douglass and Pitts ignited a slew of controversy, considering that Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years old. Her family stopped speaking to her; her children regarded the marriage as a condemnation of their mother. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a feminist, congratulated the couple. Douglass responded to the skepticism by saying that his first marriage was to someone of his mother's color, and that his second marriage was to someone of his father's color.