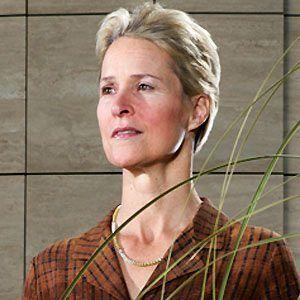

Frances Arnold

Frances Arnold was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States on July 25th, 1956 and is the Biologist. At the age of 67, Frances Arnold biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 67 years old, Frances Arnold physical status not available right now. We will update Frances Arnold's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Hamilton Arnold (born July 25, 1956) is an American chemical engineer and Nobel Laureate.

Linus Pauling Professor of Chemical Engineering, Bioengineering, and Biochemistry at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

In 2018, she received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for pioneering the application of directed evolution to engineer enzymes.

Early life and education

Arnold is the granddaughter of Lieutenant General William Howard Arnold's niece. Josephine Inman (née Routheau) and nuclear physicist William Howard Arnold are the granddaughters. She grew up in Edgewood, Pittsburgh, and the Pittsburgh suburbs of Shadyside and Squirrel Hill, all graduated from Taylor Allderdice High School in 1974. She rode off to Washington, D.C., to oppose the Vietnam War and lived on her own, as a cocktail waitress at a local jazz bar and a taxi driver.

Arnold's struggle as an adult led to a substantial number of absences from school and poor grades. Despite this, she achieved near-perfect results on standardized assessments and was determined to enroll Princeton University, her father's alma mater. She applied as a mechanical engineer major and was accepted. "Mechanical engineering] was the most feasible option and the fastest way to enroll Princeton University at the time and I never left," Arnold's motivation for studying engineering, as she wrote in her Nobel Prize interview.

Arnold received a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering from Princeton University in 1979, where she concentrated on solar energy research. In addition to the core curriculum, she took courses in economics, Russian, and Italian, and eventually imagined herself as a diplomat or CEO. After her second year away from Princeton, she went to Italy and worked in a nuclear reactor manufacturer's shop, then returned to finish her studies. She began studying at Princeton's Center for Energy and Environmental Studies, a group of scientists and engineers who at the time, Robert Socolow, were researching how to produce renewable energy sources, something that would become a focus of her later research.

Arnold, a 1979 Stanford graduate, spent time as an engineer in South Korea and Brazil, as well as at the Colorado's Solar Energy Research Institute. She worked at the Solar Energy Research Institute (now the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) in Tucson, designing solar energy plants for remote locations and assisting in the writing of UN (UN) position papers.

She continued to study biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, where she obtained a Ph.D. degree in chemical engineering in 1985 and became particularly interested in biochemistry. Her thesis research, which was carried out in Harvey Warren Blanch's lab, investigated affinity chromatography techniques. Arnold had no experience in chemistry before beginning to pursue a doctorate in chemical engineering. The graduate committee at UC Berkeley requested that she take undergraduate chemistry classes for the first year of her Ph.D. program.

Personal life

Arnold lives in La Caada Flintridge, California. In 2001, she married James E. Bailey, who died of cancer. They had a son named James Bailey. Arnold was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 2005 and underwent surgery for 18 months.

Arnold was in a common-law marriage with Caltech's astrophysicist Andrew E. Lange, who died in 1994, and the two sons, William and Joseph, were born. Lange died in 2010 after one of their sons, William Lange-Arnold, was killed in a car crash in 2016.

Traveling, scuba diving, skiing, dirt-bike riding, and hiking are among her interests.

Career

Arnold conducted postdoctoral research in biochemistry at Berkeley after receiving her Ph.D. She joined the California Institute of Technology as a visiting associate in 1986. She was promoted to assistant professor in 1986, associate professor in 1992, and full professor in 1996. In 2000, she was named the Dick and Barbara Dickinson Professor of Chemical Engineering, Bioengineering, and Biochemistry, and in 2017, she became the Linus Pauling Professor of Chemical Engineering, Bioengineering, and Biochemistry. Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen Bioengineering Center director Susan M. Rosen Bioengineering Center director in 2013.

Arnold served on the Santa Fe Institute's Science Board from 1995 to 2000. She was a member of the Joint BioEnergy Institute's Advisory Board. Arnold is the chairman of the Packard Fellowships in Science and Engineering's Advisory Panel. She served on the President's Advisory Council of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). She served as a judge for The Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering, as well as assisting Hollywood screenwriters to better represent science concepts in a variety of ways.

Arnold was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering in 2000 for bringing fundamentals of molecular biology, genetics, and bioengineering together to support life science and industry.

She is co-inventor on over 40 US patents. In 2005, she co-founded Gevo, Inc., a company that manufactures fuels and chemicals from renewable sources. Peter Meinhold and Pedro Coelho, two of her former students, co-founded Proserti in 2013 to look at pesticide alternatives for crop protection. Illumina Inc.'s corporate board has been she on the board of directors since 2016.

Arnold was appointed to Alphabet Inc.'s board in 2019, making her the third female director of the company in the company's history.

She was appointed an external co-chair of President Joe Biden's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology in January 2021. (PCAST). She is currently employed by Biden's transition team to assist in the search for scientists for positions in the administration. She says her main job now is to help choose PCAST's additional members and then get to work setting a scientific agenda for the group. "We have to reestablish the importance of science in policymaking, in decision making throughout the administration," she said. We have to reestablish the confidence of the American people in science... PCAST, I believe, will play a role in that."

Arnold is credited with pioneering the use of directed evolution to produce enzymes (biochemical molecules—often proteins) that catalyze or accelerate chemical reactions. Iterative rounds of mutation and screening for proteins with improved functionality and capability have been used to design useful biological structures, including enzymes, metabolic pathways, genetic regulatory circuits, and organisms as part of the directed evolution project. Evolution by natural selection can lead to proteins (including enzymes) that are well suited to perform biological tasks, but natural selection cannot be applied to existing sequence variations (mutations) and often occurs over long time periods. Arnold accelerates the process by inserting mutations into the underlying sequences of proteins; she then investigates the results of mutations. If a mutation enhances the proteins' function, she'll continue refining the process to optimize it further. This approach has broader ramifications because it can be used to produce proteins for a variety of uses. For example, she has used directed evolution to produce enzymes that can be used to produce renewable fuels and pharmaceutical compounds with less harm to the environment.

One advantage of directed evolution is that the mutations don't have to be completely random; rather, they can be random enough to uncover unexplored potential, but not so random as to be inefficient. The number of potential mutation combinations is staggering, but rather than simply attempting to test as many as possible, she narrows down the options, focusing on genes that are likely to have the most beneficial effect on performance and avoiding areas where mutations are likely to be, at best, neutral and in worst cases, detrimental (such as disrupting proper protein folding).

Arnold pioneered enzyme optimization, but not the first person to do so, see e.g. (Berry Hall) was a student at the University of On the 30th of June, Barry Hall was elected as the president of the United Kingdom. She developed subtilisin E's first version of unnatural environments in her seminal research, which was published in 1993. The enzyme's gene was expressed by bacteria by bacteria in four separate rounds of mutagenesis of the enzyme's gene by error-prone PCR. In the presence of DMF, the enzymes were tested for hydrolyzing the milk protein casein by growing the bacteria on agar plates containing casein and DMF. The bacteria kept the enzyme in secret, and if it were working, it would hydrolyze the casein and give a visible halo. For further rounds of mutagenesis, she chose the bacteria that had the largest halos and isolated their DNA. She created an enzyme with 256 times more activity in DMF than the original using this technique.

She has refined her techniques and applied them to a variety of selection criteria in order to optimize enzymes for specific functions. Although naturally occurring enzymes tend to be effective within a narrow temperature range, enzymes could be made from directed evolution that could be useful at both high and low temperatures, according to Sherry. Arnold has created enzymes that carry out specific enzyme functions, such as when she created cytochrome P450 to perform cyclopropanation and carbene transfer reactions in addition to improving the existing functions of natural enzymes.

She has used directed evolution to co-evolve enzymes in biosynthetic pathways, such as those involved in the manufacture of carotenoids and L-methionine in Escherichia coli (which can be used as a whole-cell biocatalyst). She has tried these techniques to biofuel production. For example, she adapted bacteria to produce the biofuel isobutanol; it can be produced in E. coli bacteria; but, E. coli produces the cofactor NADH, while E. coli produces the cofactor NADPH. She created the enzymes in the path to NADH rather than NADPH, allowing for the manufacture of isobutanol.

Arnold has also used directed evolution to produce highly specific and effective enzymes that can be used as environmentally friendly alternatives to certain industrial chemical synthesis methods. She and others using her techniques have engineered enzymes that can perform synthesis reactions more efficiently, with less by-products, and in some cases, she and others have succeeded in eliminating the need for volatile heavy metals.

She creates protein chimeras with unique functions by using structure-guided protein recombination to incorporate portions of various proteins. She used computational methods, such as SCHEMA, to determine how the parts could be combined without altering their parent structure, so that the chimeras will fold properly, and then applies directed evolution to further mutate the chimeras to optimize their functions.

Arnold, a graduate of Caltech, has worked at a laboratory that continues to investigate directed evolution and its applications in environmentally sustainable chemical synthesis and green/alternative energy, as well as the development of highly active enzymes (cellulolytic and biosynthetic enzymes) and microorganisms to convert renewable biomass to fuels and chemicals. Inha Cho and Zhi-Jun Jia's paper in Science in 2019 has been postponed until January 2, 2020, because the results were found not reproducible.

According to Google Scholar, Arnold has an h-index of 135 as of 2021.