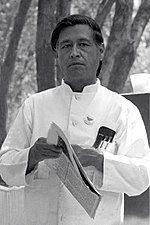

Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona, United States on March 31st, 1927 and is the Civil Rights Leader. At the age of 66, Cesar Chavez biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 66 years old, Cesar Chavez physical status not available right now. We will update Cesar Chavez's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez; Spanish: [taes]; March 31, 1927-April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights campaigner. He co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later joined the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) to form the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union, alongside Dolores Huerta. His worldview, according to Ideologically, combined leftist politics with Catholic social teachings.

Chavez spent two years in the United States Navy in Yuma, Arizona, to a Mexican American family. He moved to California, where he married, and became involved with the Community Service Organization (CSO), which helped labourers register to vote. He joined the CSO as the country's national director in 1959, a Los Angeles position. He left the CSO to co-found the NFWA, based in Delano, California, where he introduced an insurance policy, a credit union, and the El Malcriado newspaper for farmworkers. He began organizing strikes among farmworkers, most notably the 1970 Delano grape strike. In 1967, he and Larry Itliong's AWOC joined NFWA as a result of the grape strike, forming the UFW. Chavez, a Hindu liberation king, was influenced by Gandhi's words, prompt but nonviolent ways to pressure farm owners into agreeing to strikers' demands. He imbued his campaigns with Roman Catholic symbolism, mass mass, and fasts. He received a lot of help from work and leftist organizations, but the Federal Bureau of Investigation monitored him closely (FBI).

Chavez began to expand the UFW's presence outside of California by opening branches in other U.S. states. Besides pushing illegal immigrants as a leading source of strike-breakers, he spearheaded a movement against illegal immigration into the United States, which culminated in violence along the US-Mexico border and sparked schisms among many of the UFW's allies. He established a remote commune at Keene, who was interested in co-operatives as a form of group. Several California farmworkers who had previously supported him were alienated, and the UFW had lost the majority of the jobs and membership it earned in the late 1960s by his increasing loneliness and emphasis on unrelent campaigning. Jerry Brown's union with California helped pass the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, but the UFW's attempt to have its reforms enshrined in California's constitution fell short. Chavez revived communal life and exiled potential rivals, owing to the Synanon religious group's influence. In the 1980s, UFW membership dwindled, with Chavez refocusing on anti-pesticide campaigns and transitioning to true-estate construction, causing controversy over his use of non-unionized laborers.

Critics of Chavez's autocratic reign of the family, the purges of those he deemed disloyal, and the identity cult built around him, among farm-owners, who consider him a communist subordinate. He was an icon for organized labour and leftist movements in the United States, and he also became a "folk saint" among Mexican Americans. His birthday is a federal holiday in several states in the United States, although several countries are named after him, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom was awarded in 1994.

Early life

Cesario Estrada Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona, on March 31, 1927. Cesario Chavez, a Mexican who had crossed into Texas in 1898, was named after his paternal grandfather, Cesario Chavez, a Mexican who had crossed into Texas in 1898. Cesario had established a fruitful wood haulage operation near Yuma in the Sonora Desert's North Gila Valley in 1906 and purchased a farm. Cesario had brought his wife Dorotea and eight children from Mexico; the youngest, Librado, was Cesar's father. In the early 1920s, Librado married Juana Estrada Chavez. She was born in Ascensión, Chihua, and her mother had come to the United States as a child. They lived in Picacho, California, before heading to Yuma, where Juana served as a farm laborer and then an assistant to the University of Arizona's chancellor. Rita, Librado and Juana's first child, was born in August 1925, with their first son, Cesar, who died in August 1925, almost two years later. Librado and Juana built a series of buildings near the family's home in November 1925 that included a pool hall, a bookstore, and living quarters. They soon fell into debt and were forced to sell these funds in April 1929, when they were forced to sell Librado's old house, which was then owned by the widowed Dorotea.

Chavez was raised in "a typical extended Mexican family," according to Miriam Patel, who said that they were "not wealthy, well-clothed, and never hungry." The family lived in Spanish, with his paternal grandmother Dorotea largely directing his religious instruction; his mother Juana, a devotee of Santa Eduviges, was raised as a Roman Catholic. Chavez was referred to his fondness for manzanilla tea as a youth. He played handball and listened to boxing matches on the radio to amuse himself. Rita and Vicki, two sisters, and two brothers, Richard and Librado, were two of six children.

Cesario began attending Laguna Dam School in 1933; there, the speaking of Spanish was forbidden; Cesario was going to change his name to Cesar. The Yuma County local government auctioned off her farmstead to pay back taxes in July 1937, and the house and land were auctioned in 1939, following Dorotea's delaying strategies. Cesar, who saw it as an injustice against his family, was among the perpetrators of the incident, with the banks, solicitors, and the Anglo-American political system. Influenced by his Roman Catholic faith, he began to see the homeless as a source of moral integrity in society.

During the Great Depression, the Chavez family joined the growing number of American migrants moving to California. The family traveled to San José, where they first lived in a garage in the city's impoverished Mexican district, first as avocado pickers in Oxnard and then as pea pickers in Pescadero. Cesar and his family moved often, and on weekends and holidays, he joined them as an agricultural labourer. He changed colleges several times throughout California's time at Miguel Hidalgo Junior School; here, his grades were generally average, though he excelled at mathematics. He was mocked for his poverty at school, but more broadly, he suffered from anti-Latino bigotry from several European-Americans, with several establishments refusing to accommodate non-white customers. He graduated from junior high in 1962, after which he dropped formal education and joined a full-time farm worker.

Chavez joined the US Navy in 1944 and was sent to the Naval Training Center San Diego. He was stationed at the US base in Saipan in July and six months later, he was promoted to the rank of seaman first class in Guam. He was then stationed in San Francisco, where he decided to leave the Navy after receiving an honorable discharge in 1946. He returned to Delano, California, where his family had lived, and he resumed as an agricultural laborer.

Chavez joined the National Farm Labour Union (NFLU), which was the Southern Tenant Farmers Union before its 1947 affiliation with the American Federation of Labor Union (STFU). (Later, the NFLU became the National Agricultural Workers Union.) He was picking cotton fields in Corcoran, near Delano, for the NFLU. In 1947, the union called a strike on the DiGiorgio grape fields. Strikers in Arkansas' strike against cotton plantations formed "caravans" and marched around the DiGiorgio property's perimeter, calling on the workers to join them. Chavez was the leader of one of those caravans.

Chavez began dating Helen Fabela, who soon became pregnant. They married in Reno, Nevada, in October 1948; it was a double wedding, with Chavez's sister Rita marrying her fiancé at the same time. Chavez and his new wife had settled in San Jose's Sal Si Puedes neighborhood, where many of his other relatives were now living. Fernando was their first child born in February 1949, and then a second, Sylvia, followed in February 1950, and finally Linda in January 1951. The pair were born shortly after they had migrated to Crescent City, where Chavez was employed in the lumber trade. Chavez began working as an apricot picker and then as a lumber handler for the General Box Company in San Jose.

Fred Ross and Father Donald McDonnell, both European-Americans whose activism was mainly within the Mexican-American community, were befriended here. Chavez assisted Ross in the establishment of his Community Service Organization (CSO) in San Jose, and he was involved in voter registration drives. He was shortly elected vice president of the CSO chapter. He was also assisting McDonnell in the construction of Sal Si Puedes' first purpose-built church, the Our Lady of Guadalupe church, which opened in December 1953. McDonnell lent Chavez books to the young man, encouraging him to develop a love of reading. Among the books were biographies of saint Francis of Assisi, the United States labor organizers John L. Lewis and Eugene V. Debs, and Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian freedom campaigner who introduced Chavez to the idea of nonviolent resistance.

Early activism

Chavez was laid off by the General Box Company in late 1953. Ross later won funds so that Chavez would be able to serve as an organizer, while the CSO could use Chavez as an organizer. We're on the lookout for other chapters in California. He has worked in this field, traveling through Decoto, Fresno, Brawley, San Bernardino, Madera, and Bakersfield. Many of the CSO chapters fell apart after Ross or Chavez stopped running them, and Saul Alinsky advised them to join the chapters, of which there were more than twenty, into a self-sustaining national body. Chavez returned to San Jose in late 1955 to revive the CSO chapter so that it could maintain an employed full-time organizer. He opened a rummage store, arranged a three-day carnival, and sold Christmas trees, but the store suffered a lot.

He migrated to Brawley in early 1957 to revive the chapter there. His family was repeatedly uprooted as a result of his repeated relocation; he saw little of his wife and children; and he was absent for the birth of his sixth child. Chavez became disillusioned with the CSO, feeling that middle-class members were increasingly influential and were pushing its priorities and allocating funds in directions he disapproved of; for instance, he opposed the decision to hold the organization's 1957 convention in Fresco's Hacienda Hotel, arguing that its rates were prohibitive for poorer residents. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began monitoring Chavez and opening a file on him in the wake of the wider context of the Cold War and McCarthyite fears that leftist activism was a front for Marxist-Leninist organizations.

The United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) paid $20,000 to the CSO for the former's opening of a branch in Oxnard, Alinsky's nephew; Chavez became the country's chief organizer, working with the majority of Mexican farm laborers. Chavez, a narcotics activist in Oxnard, promoted voter registration. He has consistently heard complaints from local Mexican-American laborers that they were being routinely passed over or fired in order to ensure that employers could hire cheaper Mexican guest employees, or braceros in breach of federal law. He established the CSO Employment Committee to combat this trend, which included an "registration campaign" in which unemployed farm-workers could sign their name to show their enthusiasm for work.

Hector Zamora, the head of the Ventura County Farm Labor Association, was the object of the committee's report, who supervised the majority of local employees. It also used sit ins of workers to raise the profile of their cause, a tactic also used by proponents of the civil rights movement in the southern United States at the time. It was also a success in getting companies to swap braceros with unemployed Americans. Its campaign also made sure federal officials started properly investigating abuses surrounding the use of braceros, getting promises from the state farm placement service that they would seek out unemployed Americans rather than insisting on bracero employees. The Employment Committee was first posted from the CSO to the UPWA in May.

Chavez descended on Los Angeles in 1959 to become the CSO's national director. He, his wife, and (now) eight children all settled in Boyle Heights, a predominantly Mexican suburb. The CSO's financial situation was bad, and even his own salary was in jeopardy, according to him. To keep the company afloat, he fired several organizers. He tried to find funds by organizing a life insurance scheme among CSO members, but the scheme was unsuccessful. The CSO obtained funds from wealthy contributors and businesses under Chavez, mainly to finance short-term goals for a specific period of time. For example, the California American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) paid $12,000 to implement voter registration schemes in six counties with high Mexican populations. Katy Peake, a wealthy benefactor, then gave it $50,000 to run California's farm workers for a three-year period. The CSO was able to get the state pension to non-citizens who were permanent residents under Chavez's leadership. Chavez resigned after the ninth annual CSO convention in March 1962.

Chavez and his family immigrated to Delano, California, an agricultural area in the southern San Joaquin Valley, where they rented a house on Kensington Street in April 1962. He was planning to establish a farm worker union, but he told people that he was only doing a census of farm workers to determine their needs. He started forming the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), referring to it as a "step" rather than a trade union. Huerta became his "indispensable, lifelong ally" in this initiative, both by his wife and Dolores Huerta, according to Pawel. The Reverend Jim Drake and other supporters of his project were among the California Migrant Ministry's most prominent supporters; although a Roman Catholic Chavez was initially suspicious of these Protestant preachers, he later came to regard them as key allies.

Chavez spent his days in the San Joaquin Valley, working with employees and encouraging them to join his group. At the time, he lived off a mixture of unemployment insurance, his wife's salary as a farmworker, and gifts from colleagues and sympathizers. He formalized the Federation at a convention in Fresno on September 30, 1962. Chavez was elected general-director of the company by delegates. Members would also begin paying monthly dues of $3.50 if the association had a life insurance policy in place. The group adopted the phrase "viva la cause" ("long live the cause") as well as a flag with a black eagle on a red and white background. Chavez was elected president at the organization's constitutional convention in Fresno in January 1963, along with Huerta, Julio Hernandez, and Gilbert Padilla as its vice presidents.

Chavez needed to control the NFWA's course, but to that end, he made sure that the officer's position was largely ceremonial, with most of the organization in the custody of the employees, led by him. Chavez was retained as the NFWA's second convention in Delano, 1963, although the presidency's position was postponed. He started collecting membership fees before establishing an insurance plan for FWA members in the year. He formed a credit union for NFWA members later this year, after the federal government refused to give him one. Volunteers from other parts of the country were recruited by the NFWA. Bill Esher, one of these, became the editor of El Malcriado, the company's newspaper, who then increased its print run from 1000 to 3000 to satisfy demand right after launch.

The NFWA was initially based out of Chavez's house, but in September 1964 the group relocating its headquarters to an abandoned Pentecostal church in Albany Street, West Delano. The association has more than doubled both its income and expenditures during its second full year of operation. As it became more stable, it began to prepare for its first attack. Rising grafts pleaded for support in arranging their strike for improved working conditions in April 1965. Mount Arbor and Conklin were mainly attacked by the strike. The workers were hit by the NFWA on May 3, and after four days the growers decided to increase wages, and the strikers returned to work. Chavez's name began to filter through leftist activist circles around California after this success.

Later life

Chavez was a picket in Yuma in June 1978 as part of his cousin Manuel's Arizona melon strike. Chavez was put into the county jail for a night because this was an injunction. By 1978, vegetable workers' outrage at the UFW had risen; they had been angered by the company's incompetency, especially in the running of its medical program. The UFW lost two-thirds in the 22 farmworker elections that took place between June and September 1978. Chavez initiated Plan de Flote to reclaim the vegetable pickers' trust and loyalty. Chavez orchestrated a new strike over wages in the hopes that wage increases would minimize the UFW's losses; the union initiated wage protests in January 1979, only days after the union's labour deals had ended. In the protest, eleven lettuce growers in the Salinas and Imperial Valleys were included, raising lettuce prices.

During the strike, the picketers trespassed on the Mario Saikhon company grounds and tried to force away those who were still working. Rufino Contreras, the foreman and other workers, were smuggish, and one picket was killed. Chavez pleaded for the strikers not to resort to violence, and Contreras' father led a three-mile candlelit funerary parade that attracted 7000 people. Ganz and other strike planners had planned a show of tenacity in June, whereby strikers rushed into the Salinas field to cause chaos. This resulted in violent protests; several people were shot with stab wounds and 75 people were arrested; several others were injured; and all were detained. Chavez was accused of terrorism as a result of the assault; Chavez chastised Ganz for arranging the protest without his permission. He then led a 12-day march from San Francisco to San Jose, beginning with a fast on the sixth day. He greeted strike leaders at a UFW convention in Salinas. The strike had been too costly for the UFW, according to him, and that it should be ended and replaced by a boycott movement. These plans were dismissed by the strike's chiefs. Many growers decided to work with the UFW in August and September, but others were turned away and the union was broken. Chavez argued for a boycott, implying that the union could use alcoholics from the cities to finance the boycott campaign, which the majority of the executive board rejected.

The growers decided to compensate paid employees' representatives, whose jobs it would be to ensure a positive working relationship between the growers and the UFW under the new terms. In May 1980, Chavez brought these paid employees to La Paz for a five-day training session. Ganz, who was growing distant from Chavez, helped them tutor them. Chavez summoned all employees to a meeting in La Paz in May 1981, where he reiterated that spies were attempting to undermine it and overthrowrown him. He arranged for more of his loyalists to be included on the executive board, but there are currently no farmworkers on the board. The paid representatives nominated some of their own choices rather than Chavez's to go on the board at the UFW Fresno convention in September 1981. Chavez's supporters received leaflets claiming that the paid representatives were puppets of "the two Jews" Ganz and Cohen, who were attempting to damage the relationship. Chavez had been accused of antisemitism, which had prompted rumors of antisemitism. Chavez suggested a bill that if 8% of employees at a ranch signed a petition, the representatives of the ranch would be obliged to vote for Chavez's chosen candidates, aiming to destabilize the compensated representatives. The bill was accepted.

All of those who had objected Chavez's choices at the convention by October had been dismissed. They retaliated by starting a fast in protest outside the UFW's Salinas office. Nine of them went back to Chavez in federal court, alleging that he had no right to fire them from positions they had been elected to represent by their peers in the fields. Chavez filed a counter-suit, suing them for libel and slander. He told a reporter that he was trying to intimidate the protester's lawyer in doing so, something that caused poor publicity for the UFW. Chava Bustamante, one of the protesters, joined the California Rural Legal Assistance group, where the UFW started picking up Bustamante's offices in an attempt to get Bustamante fired. Chavez denied that the paid representatives were ever elected in court, alleging that they were appointed by him personally but giving no evidence to back up this assertion. Judge William Ingram of the United States District Court dismissed Chavez's argument by finding that the dismissal of the paid employees had been unlawful. The UFW appealed the decision, which dragged on for years, until the paid representatives ran out of funds to continue.

Senior UFW members in Texas and Arizona were forced to leave the union and form their own organizations, such as the Texas Farm Workers Union and the Maricopa County Organizing Project, owing to Chavez's hostility to illegal migrants. Chavez and his cousin Manuel Manuel went to Texas to try to rally resistance against the schism. Manuel also went to Arizona, where he introduced a number of steps to discredit the new group. As a result, investigative journalist Tom Barry began looking into Manuel's activities. It was revealed that under a pseudonym he had become a melon grower in Mexico and that he had launched attacks among American melon pickers as a way to increase the demand for his own produce. The UFW's image was further tarnished after the magazine Reason revealed that the union improperly invested nearly $1 million in federal programs. Following the reports, federal and national probes followed, confirming these allegations. When the Internal Revenue Service found that the union owes $390,000 in back social security and federal unemployment taxes, the government begged the UFW to return over $250,000 in funds.

In 1982, the UFW held a commemoration of its first convention in San Jose. Chavez's father died in October of this year, and his funeral was held in San Jose. Chavez was also participating in a broader variety of leftist activities. Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda's fund-raising dinner for their Campaign for Economic Democracy was co-chaired by him. He appeared at Peace on Sunday, an anti-nuclear demonstration, in the summer of 1982. The UFW had been one of California's most prominent political contributors. Its political contributions were often hidden from the public and funneled through intermediary committees. Thousands of dollars were donated by Howard Berman's campaign to unseat Leo McCarthy as the Speaker of the California State Assembly because of McCarthy's role in defeating Proposition 14. Many Democrats feared that Berman would be enslaved to Chavez, so they praised Willie Brown, who swept the election. Willie Brown was also given a UFW grant by the University of Willie Brown.

The UFW's membership, as well as the subsequent membership dues, began to decline. In January 1983, UFW jobs spanned 30,000 employees, but by January 1986, the number had decreased to 15,000. Although the dues that membership brought in in in in 1982 were $2.9 million, three years later, it had decreased to $1 million. In the United States, there existed a burgeoning Latino middle-class by the 1980s. Although Chavez feared the aspirational strategy that had helped working-class Latinos become middle-class, he understood that this provided the UFW with a larger support base. He announced the founding of the Chicano Lobby, a new non-profit group at the 1983 UFW convention. The eldest son Fernando Chavez of San Antonio's eldest uncle Fernando gave addresses at the Lobby's launch. The UFW needed to raise its political profile in the wake of its depletioning membership. Chavez delivered a speech to the Commonwealth Club of California in November 1984. The UFW opened a print shop, drawing on politicians who were eager to court the Latino vote more often.

Chavez and Red Coach Lettuce went on strike against grapes and Red Coach Lettuce because their parent company, Bruce Church, had refused to sign a deal with the UFW. Chavez, a California supermarket chain, has called off a boycott of Lucky. His aim was to warn the supermarket that the UFW will damage Latino patronage. Chavez had noticed that the Christian Right was starting to use new computer technologies to pique prospective followers and that the UFW should do the same. They were able to target particular groups of people who were sympathetic to their cause, such as Hispanics, middle-class African Americans, and liberal professionals living in major cities through this. The UFW also acquired television ads, which it used to raise funds as part of its protest, which it used to raise funds.

Chavez's campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s remained largely concerned with the use of pesticides in the fields, which he argued posed a risk both to farmworkers and consumers. The UFW raised over $100,000, as well as donated equipment, to build its own pesticide research lab, but this never opened. Ralph Nader's campaign as a leader in anti-pesticide movements rallied his help. Chavez argued that if customers boycotted the company's products, the growers would stop using pesticides, which would be justified. The UFW said that the high incidence of childhood cancer in McFarland represented proof of how pesticides affected humans; they used a video of some of these children in a 17-minute film called The Wrath of Grapes. Many of the parents were outraged, and others blasted the United Union, alleging that the union was exploiting their children for their own benefit. The children's agitated mother demanded that they leave at the funereal procession of a 14-year old boy who died of cancer, where they carried union flags.

Jerry Brown, the governor of California, resigned in 1982. Republican George Deukmejian, who had the support of the state's growers, was fired, but the ALRB's authority eroded under Deukmejian. The UFW was found to be $1.7 million in interest for the union's unlawful conduct against the Maggio firm in 1979. In July 1988, Chavez began another public fast at Forty Acres, as the UFW's protest of Bruce Church products failed to gain traction. Three of Robert Kennedy's children visited, generating media buzz for the fast. Chavez broke the fast at a party attended by Democratic politician Jesse Jackson for 19 days. Chavez accused more people of being saboteurs at La Paz, sparking more purges. Hartmire was one of those fired out, resigning in January 1989. Many of those at La Paz were shot before Chavez could threaten them, and the neighborhood became increasingly depopulated. Chavez, meanwhile, continues to be honoured and praised. The Mexican government gave him the Order of the Aztec Eagle in November 1989, the first of which he had a private audience with Mexican President Carlos Salinas. After Chavez's resignation in October 1990, Coachella became the first district to name a school; he attended the dedication service.

With membership dues decreasing, the UFW has increasingly turned to commercial activities as a means of raising funds. Through Ell Taller Grafico Speciality Advertising (ETG), which had Chavez as its chair, it began marketing UFW branded products. Chavez also started working as a housing developer, collaborating with Fresno businessman Celestino Aguilar. They bought houses that were underwater, renovated them, and then sold them on. They went from foreclosures to high-end custom built houses and subsidised apartment blocks in a row. Chavez and Aguilar formed American Liberty Investments in order to mask the UFW's involvement in these projects. They also founded Ideal Minimart Corporation, which built two strip malls and operated a check-cashing store. Bonita Construction, Richard's company, was hired for part of the work. The Fresno Bee revealed later that the bulk of the UFW's housing projects had been constructed by non-union contractors. The trade unions representing the building unions expressed outrage at the news, claiming that they had previously given the UFW financial assistance. The incident later became known as a "embarrassment," according to the New Yorker.

The UFW continued to promote Chavez as a hero in the early 1990s, particularly on university and college campuses. In 1990, he appeared at 64 shows, each earning an average of $3,800 per appearance. In 1991, he founded the "Public Action Speaking Tour" of U.S. colleges and universities. His keynote address at these conferences addressed the challenges facing farmworkers, the dangers of pesticide use, the alliance of agribusiness and the Republican Party, and his belief that boycotts and marches were a better way to achieve reform than political politics.

Chavez's mother died in December 1991 at the age of 99. Chavez's mentor Ross died in September 1992, the following year. At his funeral, Chavez penned a eulogy. Chavez's last years saw the UFW's participation in a court fight with Bruce Church. The corporation had sued the union, arguing that it libelled them and had illegally sued supermarkets to prohibit them from selling Red Coach lettuce. A jury delivered a $5.4 million verdict against the UFW in 1988, but this appeal was dismissed in the appeals court. The lawsuit was then remanded for trial on narrower grounds. In 1993, Chavez was summoned to appear in front of a Yuma court. The stakes were high; a decision against the UFW would have been financially devastating. Chavez remained at the home of a San Luis supporter during the investigation. He died in bed on April 23, so it was there that he died in bed. He was 66 years old at the time.

Chavez's body was flown by a chartered plane to Bakersfield. The autopsy revealed inconclusive, with the family stating that he died of natural causes. Chavez had already agreed that he wanted his brother Richard to build his coffin and that his funeral should be held in Forty Acres. His body was on display in state, where tens of thousands of people visited it. In Delano, 120 pallbearers took turns to carry the coffin. Chavez was then buried in a private ceremony in La Paz.

Personal life

When Chavez returned home from his military service in 1948, he married Helen Fabela, his high school sweetheart. The couple migrated to San Jose, California. Fernando (b.1959), Sylvia (b.1952), Eloise (b.1952), Elizabeth (b.1958), and Anthony (b.1958) were among his eight children with his wife. Helen shucked the limelight, a characteristic Chavez admired. Although she was in charge of the union, she concentrated on raising the children, cooking, and housekeeping. His infidelity with a number of women became common knowledge among senior UFW figures, who kept his information private so as not to damage his reputation as a devoted Catholic family man. Helen received a love letter from another woman to Chavez, but after she left La Paz and lived with one of her daughters in Delano, she briefly left La Paz. Chavez's children resent the union and showed no enthusiasm for it, although most ended up working for it. Fernando, Chavez's eldest son, was the only one to graduate college; Chavez's relationship with Fernando was tense due to his son's inability to be middle-class;

Chavez shared traditional views on gender roles in his youth and was little influenced by the second wave feminism that was contemporane with his activism. Men in his movement, with women mostly restricted to background roles such as secretaries, nurses, or child care; the major exception was Huerta. Chavez had a close working relationship with Huerta. They became mutually dependent, and although she did not hesitate to raise concerns with him, she frequently deferred to him. They often argued during their work relationship, a trend that has heightened in the latter part of the 1970s. When Huerta was under pressure, she became Chavez's "whipping baby." He never had close friendships outside of his family, claiming that friendships distracted him from his political activism.

Chavez was short and had jet black hair and was sporting jet black hair. He was quiet, and Bruns described him as "outwardly shy and unimposing." He suffered from persistent back pain throughout his life, as well as many farm workers. He could be self-conscious of his lack of formal education and was uncomfortable dealing with wealthy individuals. He has often myologized his own life tale when speaking with reporters. Chavez was not a great orator, but his authority lay not in words, but in actions, not in words, according to Pawel. Bruns wrote that she was "not an articulate speaker" and that she "had no natural abilities as a public speaker," and that he "had no inherent talent as a public speaker." He was soft-spoken, and Pawel had a "intuitive, conversational voice" and was "good at reading people," according to Pawel. He was unable to delegate or rely on others. He preferred to tackle every project personally. He was also able to react quickly and decisively to events.

Bruns described Chavez as combining a "remarkable tenacity" with a "sense serenity." He started his working day at 3.30 a.m. and would often continue until 10 p.m.; a dedicated employee. "I just sleep, eat, and work," he said. "I do nothing else." Chavez, according to Pawel, was both "charming, attentive, and humble" as well as being "single-minded, demanding, and ruthless." He usually did not attack one of his volunteers or staff members in a private manner, but he might defame them in a public debate on occasion. He referred to his own life as a struggle against injustice and showed a dedication to self-sacrifice. "Chavez flourished on the ability to assist people and in the way that made him feel," Pawel said. "He will do in thirty minutes what it would take me or someone else 30 days," Ross, a Chavez friend and colleague, said. Chavez's "nobleble" quest to be the "one and only farm labor leader," Pawel said. He was stubborn, and would not have come back down unless he had taken a stand. He would not accept criticism of himself, but would deny it.

Chavez, a Catholic, whose faith influenced both his social activism and his personal outlook. He rarely missed Mass and preferred to open all of his meetings with either a Mass or a prayer. He also liked to meditate in private. He went vegetarian in 1970, vowing that "I wouldn't eat my dog." Cows and dogs are about the same." He also shunned most dairy products, except cottage cheese, as part of this diet. He credited this diet with relieving his chronic back pain. He also avoided eating processed foods. Traditional Mexican and Chinese cuisines were among his favorite foods.

Chavez adored Duke Ellington's music and big band bands; he loved dancing. He was also an amateur photographer and keen gardener, growing vegetables and composting himself. For the bulk of his adult life, he kept German shepherd dogs for personal security; two of those he kept at La Paz were named Boycott and Huelga. Chavez owned several of his papers, letters, minutes of meetings, as well as tape recordings of many interviewers, and at the suggestion of Philip P. Mason, they were donated to the Walter P. Reuther Library, where they are kept. He disliked phone calls, suspecting that his phone line was bugged. He preferred to see challenges faced by his travel not as signs of innocent blunders but rather as deliberate sabotage.

Chavez was self-educated, with Pawel noting that he was "disinclined to analyze information." Once Chavez accepted an idea, he would dedicate himself entirely to it.