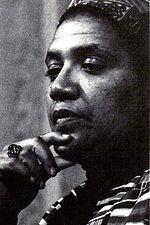

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde was born in New York City, New York, United States on February 18th, 1934 and is the Poet. At the age of 58, Audre Lorde biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 58 years old, Audre Lorde physical status not available right now. We will update Audre Lorde's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Audre Lorde (born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934-1992) was an American writer, feminist, feminist, librarian, and civil rights advocate.

She is best known for her technical proficiency and emotional expression, as well as her poems that express indignation and condemnation of various social and economic injustices she encountered throughout her life.

The majority of her poems and prose concern with issues related to civil rights, feminism, lexianism, sickness, and disability, as well as the investigation of black female identity. Lorde said specifically about non-intersectional feminism in the United States: "Those of us who belong outside this society's image of acceptable women; those of us who have been born in the crucibles of difference – those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are older – know that survival is not an academic skill.

It's learning how to recognize our differences and make them strengths.

The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.

They may allow us to beat him at his own game for a brief period of time, but they will not allow us to bring about real change.

And this is only troubling to those women who still identify the master's house as their only source of assistance."

Early life

Lorde was born in New York City on February 18, 1934, to Caribbean immigrants. Frederick Byron Lorde (also known as Byron) was born on the island of Carriacou and her mother, Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde, was born in Barbados and died. Lorde's mother had mixed ancestry but could have passed for Spanish, which was a point of pride for her family. Lorde's father was darker than the Belmar family's, and they only accepted the couple's marriage due to Byron's charm, passion, and tenacity. The new family migrated to Harlem. Lorde grew up hearing her mother's tales about the West Indies, nearsighted to the point of being legally blind and the youngest of three children (her two older sisters were named Phyllis and Helen). She learned to read when she was four years old, and her mother taught her to write at the same time. When she was in eighth grade, she wrote her first poem.

Audrey Geraldine Lorde was born as Audrey Geraldine Lorde and explained in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the logical symmetry of the "e" endings in the two side-by-side names "Audre Lorde" than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.

From a young age, Lorde's relationship with her parents was difficult. She spent very little time with her father and mother, who were both busy running their real estate companies in the tumultuous economy following the Great Depression. When she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. Lorde's relationship with her mother, who was highly suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde had) and the outside world in general was characterized by "tough love" and strict follower of family laws. Lorde's difficult friendship with her mother featured prominently in her later poems, including Coal's "Story Books on a Kitchen Table."

Lorde wrestled with communication as a child and learned to appreciate the beauty of poetry as a form of expression. In fact, she refers to poetry as being interested in poetry. Audre would reply by reciting a poem if she was feeling." she also memorized a lot of poetry and would use it to communicate, to the extent that "If asked how she was feeling." As she aged 12, she began writing her own poetry and interacting with others at her high school who were considered "outcasts" as she felt she was.

Lorde, a raised Catholic, attended parochial schools before embarking on to Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students. She graduated in 1951. Lorde, a student at Hunter, published her first poem in Seventeen magazine after her school's literary journal dismissed it for being inappropriate. Lorde attended poetry workshops sponsored by the Harlem Writers Guild, but she admitted that she was still a bit of an outcast from the Guild. She was refused because she was "both crazy and queer, but [they hoped] I would grow out of it all."

Zami's father died as a result of a stroke around New Year's 1953.

Personal life

Lorde married Edwin Rollins, a white, gay man, in 1962. Elizabeth and Jonathan were divorced by Rollins in 1970 after having two children. Lorde became the head librarian at the Town School Library in New York City in 1966, where she remained until 1968.

Frances Clayton, a white lesbian and psychology researcher who became her romantic partner until 1989, met her while in Mississippi in 1968. Lorde's marriage lasted for the remainder of his life.

After meeting Mildred Thompson in Nigeria at the second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, Lorde was briefly involved with the artist and painter after she met her in Nigeria at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Thompson lived in Washington, D.C., while she was under surveillance.

Lorde and her life partner, black feminist Dr. Gloria Joseph, lived together on Joseph's native land of St. Croix. Lorde and Joseph were known as a pair since 1981, but after Lorde's liver cancer diagnosis, she and Joseph officially left Clayton for Joseph, heading to St. Croix in 1986. Until Lorde's death, the two couples lived together. They founded the Che Lumumba School for Truth, Women's Alliance of St. Croix, USA, Sisterhood in St. Croix, South Africa, and Doc Loc Apiary.

Career

She spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico in 1954, a period she characterized as a period of hope and renewal. She established her identity as both a lesbian and a poet during this period. On her return to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College and graduated in the class of 1959. She spent time as a librarian, continued writing, and became a regular participant in the Greenwich Village gay culture. She continued her education at Columbia University, earning a master's degree in library science in 1961. During this time, she served as a public librarian in Mount Vernon, New York.

Lorde was the author-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 1968. Lorde's time at Tougaloo College, as well as her time at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for her as an artist. Many of whom were eager to address the civil rights issues of the day, she led workshops with her young, black undergraduate students. She reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her "crazy and queer" identity, but also to pay attention to the academic aspects of her craft as a poet through her interactions with her students. Cables to Rage, her book of poems, came from her time and experiences in Tougaloo.

Lorde lived on Staten Island from 1972 to 1987. During that time, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, in addition to writing and teaching.

Lorde became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press in 1977 (WIFP). WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing company. The group is working to increase female contact and better connect the public with the help of women in media.

Lorde served at Lehman College from 1969 to 1970, then as a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (a part of the City University of New York, CUNY) from 1980 to 1981. She fought for the establishment of a black studies center in the United States. She returned to teach at Hunter College (also CUNY) in 1981 as the distinguished Thomas Hunter chair.

Kitchen Table, the first American bookstore for women of color, was founded in 1980 by Barbara Smith and Cherriste Moraga. Lorde was the Lord Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.

Lorde was one of the founders of the Women's Coalition of St. Croix, an organization dedicated to helping women who have suffered sexual assault and intimate partner violence. She also helped establish Sisterhood in Support of Sisters (SISA) in South Africa in the late 1980s to help black women in South Africa who were impacted by apartheid and other forms of injustice.

Audre Lorde was a member of a group of black women writers who had been invited to Cuba in 1985. The Black Scholar and the Union of Cuban Writers sponsored the trip. As black women writers, she embraced the shared sisterhood. Nancy Morejon and Nicolas Guillen, Cuban poets, were on tour. They debated whether the Cuban revolution had really changed white nationalism and the position of lesbians and gays there.

Lorde established a visiting professorship at Berlin's Free University in 1984. Dagmar Schultz, a FU lecturer who had attended her at the UN "World Women's Conference" in Copenhagen in 1980, had invited her. During her stay in Germany, Lorde became an integral figure of the then-nascent Afro-German movement. Audre Lorde coined the phrase "Afro-German" in 1984 and, in the ensuing of the Berlin black revolution, she joined a group of black women campaigners, giving rise to the Black movement in Germany. During her many trips to Germany, Lorde became a mentor to a variety of women, including May Ayim, Ika Hügel-Marshall, and Helga Emde. Lorde viewed language as a powerful form of resistance rather than fighting systemic problems by violence, and encouraged the women of Germany to speak up rather than fight back. Lorde's influence on Germany went beyond Afro-German women; she helped raise the possibility of intersectionality across racial and ethnic boundaries.

The impact of Lorde's impact on the Afro-German movement was explored in Dagmar Schultz's 2012 film. Audre Lorde: The Berlin Film Festival, Berlin, was a member of the Berlin Film Festival, and its World Premiere was held at the 2012 Berlin International Film Festival. The film has toured film festivals around the world and is now being seen at festivals until 2018. Seven prizes have been given to the documentary, including the Best Documentary Award at the International Film Festival for Women, Social Issues, and Zero Discrimination, as well as the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the Barcelona International LGBT Film Festival. Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years revealed that Lorde was still receiving no praise for her contributions to the theories of intersectionality.