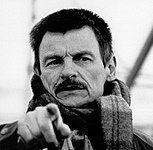

Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Tarkovsky was born in Zavrazhye, Russia on April 4th, 1932 and is the Director. At the age of 54, Andrei Tarkovsky biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 54 years old, Andrei Tarkovsky has this physical status:

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky (4 April 1932 – September 29, 1986) was a Russian filmmaker, writer, and film critic.

He is widely regarded as one of the best filmmakers in cinema history and one of Russia's most influential filmmakers.

Ivan's Childhood (1972), Mirror (1975), and Stalker (1979) Andrei Rublev (1969), both exploring spiritual and metaphysical subjects, as well as their preoccupation with nature and memory.

Tarkovsky left the country in 1979 and made his last two films in Italy and Sweden respectively, after years of creative tension with Soviet officials over his work;

Sculpting in Time, a film about cinema and art, was also published in 1986.

He died of cancer later this year. Tarkovsky's career included numerous awards at the Cannes Film Festival (including the FIPRESCI award, the Ecumenical Jury Prize, and the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury) and the winner of the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival for his debut film Ivan's Childhood.

He was humbly honoured the Lenin Prize in the Soviet Union in 1990.

In Sight & Sound's 2012 survey of the 50 greatest films of all time, three of his films —Andrei Rublev, Mirror, and Stalker — were included.

Life and career

Andrei Tarkovsky was born in the village of Zavrazhye in the Ivano Industrial Oblast's Yuryetsky District (modern-day Kadytsky District of the Kodysahytsky District of Moscow, Russia), to poet and translator Arseny Aleksandrovich Tarkovich Tarkovich Tarkovich Tarkovich, a native of Yelysavethrad (now Kropytsky, Ukraine), and translator Ars

Aleksandr Karlovich Tarkovsky, Andrei's paternal grandfather, (in Polish: Aleksander Karol Tarkowski) was a Polish nobleman who worked as a bank clerk. Maria Danilovna Rachkovskaya, a Romanian language tutor, came from Iași. Vera Nikolayevna Vishnyakova (née Dubasova) of Andrei's maternal grandmother was a descendant of a Russian nobility family dating back to the 17th century; one of her relatives was Admiral Fyodor Dubasov, who was forced to hide during Soviet times. She married Ivan Ivanovich Vishnyakov, a native of the Kaluga Governorate who studied law at the Moscow State University and served as a judge in Kozelsk.

Tarkovsky's ancestors on his father's side were princes from the Shamkhalate of Tarki, Dagestan, according to the family legend, although his sister Marina Tarkovskaya, who did extensive research on their genealogy, called it "a myth, even a prank of sorts."

Tarkovsky spent his childhood in Yuryevets. He was characterized as both active and popular by childhood friends, as well as being firmly embedded in the action. His father left the family in 1937 and then joined the army in 1941. He returned home in 1943 after being shot in one of his legs (which would eventually need to amputate due to gangrene). Tarkovsky and his mother continued to Moscow, where she and her sister Marina joined her and her sister Marina to Moscow, where she worked as a proofreader at a printing press.

Tarkovsky was admitted to No. 2 in 1939, 1939. 554 people have been killed. During the war, the three children were evacuated to Yuryevets, where they grew with his maternal grandmother. The family returned to Moscow in 1943. Tarkovsky continued his studies at his old school, where poet Andrei Voznesensky was one of his classmates. He studied piano at a music academy and attended art school classes. The family lived on Shchipok Street in Moscow's Zamoskvorechye District. He was in the hospital with tuberculosis from November 1947 to spring 1948. In his film Mirror, several themes of his childhood — the evacuation, his mother and her two children, and the hospital stay — all feature prominently.

Tarkovsky was a student and a failure in his time at school. He maintained his studies, and the Oriental Institute in Moscow, a Moscow branch of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union, taught Arabic from 1951 to 1952. Despite learning Arabic and was a good student in his first semester, he did not finish his studies and moved out to work as a prospector at the Academy of Science Institute for Non-Ferrous Metals and Gold. He was on a year-long research trip to the river Kureyka near Turukhansk, Czechoyarsk Province, where he was born in the Krasnoyarsk Province. Tarkovsky decided to study film during this period in the taiga.

Tarkovsky graduated from the research expedition in 1954 and was accepted into the film-directing program. He was in the same class as Irma Raush (Irina), who married in April 1957.

Young film makers had a blast in the early Khrushchev period. Annual film production was low before 1953, and veteran filmmakers helmed most films. More films were produced after 1953, some of which were directed by young directors. Khrushchev Thaw eased Soviet social pressures a little and allowed for a small amount of European and North American literature, films, and music. Tarkovsky was able to see films of the Italian neorealists, French New Wave, and of directors such as Kurosawa, Buuel, Bergman, Bresson, Wajda (whose film Ashes and Diamonds inspired Tarkovsky) and Mizoguchi.

Mikhail Romm, Tarkovsky's mentor and mentor, worked with many film students who would later become influential film directors. Tarkovsky made his first student short film, The Killers, in 1956, from Ernest Hemingway's short story. In 1959, There Will Be No Leave Today followed the longer television film There Will Be No Leave Today. Both films were created as a result of a joint project between the VGIK students. Aleksandr Gordon, a classmate who married Tarkovsky's sister, edited, and appeared in the two films with Tarkovsky.

Grigory Chukhray, a film director who was studying at the VGIK, had a major influence on Tarkovsky. Chukhray offered Tarkovsky a position as assistant director for his film Clear Skies after being impressed by his student's talent. Tarkovsky initially showed keenness but then decided to concentrate on his studies and his own projects.

Tarkovsky met Andrei Konchalovsky during his third year at the VGIK. They had a lot in common; they liked the same film directors and shared ideas about cinema and films. They wrote Antarctica – Distant Country in 1959, which was later released in the Moskovsky Komsomolets. Tarkovsky wrote the script to Lenfilm, but it was turned down. They were more popular with the script The Steamroller and the Violin, which they sold to Mosfilm, were more profitable. This was Tarkovsky's graduation project, gaining his diploma in 1960 and winning the First Prize at the New York Student Film Festival in 1961.

Ivan's Childhood, Tarkovsky's first film, was released in 1962. He had inherited the film from director Eduard Abalov, but had to cancel the order due to a deadline. Tarkovsky received international recognition and received the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival in 1962. Tarkovsky's first son Arseny was born on September 30th (called Senka in Tarkovsky's diaries) in the same year.

Andrei Rublev, the fifteenth-century Russian icon painter, produced the film Andrei Rublev in 1965. Except for a single screening in Moscow in 1966, Andrei Rublev was not involved, and he was quickly dismissed after completion due to problems with Soviet officials. Tarkovsky had to cut the film multiple times, resulting in several different lengths. In 1971, a cut version of the film was widely distributed in the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the film had a budget of over 1 million rubles, which was a significant sum for the time. In 1969, a copy of the film was shown at the Cannes Film Festival and received the FIPRESCI award.

In June 1970, he divorced his wife, Irina. He married Larisa Kizilova (née Egorkina), who had been a production assistant for the film Andrei Rublev for the first time since 1965 (they had been living together since 1965). Andrei Andreyevich Tarkovsky (nicknamed Andriosha, implying "little Andre" or "Andre Junior") was born in the same year on August 7th.

In 1972, he completed Solaris, an extension of Stanis Lem's book Solaris. He and screenwriter Friedrich Gorenstein were together on this project as early as 1968. The film was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, won the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury, and was nominated for the Palme d'Or.

He shot Mirror, a highly autobiographical and unconventionally structured film that focuses on his childhood and includes some of his father's poems from 1973 to 1974. Tarkovsky portrayed the plight of childhood affected by war in this film. Tarkovsky had been working on the film script for this film since 1967, under the guile of Confession, White Day, and A white, white day. The film was not well-received by Soviet authorities from the start due to its content and its apparent elitist appearance. The film was released in the "third category," a severely limited release, and it was only allowed to be seen in third-class cinemas and workers' clubs. No prints were produced and no money was returned by the film-makers. The film makers were also placed in risk of being accused of misusing public funds in the third category, which could have serious ramifications for them. These challenges are likely to have pushed Tarkovsky to try going overseas and filming a film outside of the Soviet film industry.

Tarkovsky appeared in the film adaptation Hoffmanniana about German writer and poet E. T. A. Hoffmann during 1975. Hamlet, his first stage performance, was directed at the Lenkom Theatre in Moscow in December 1976. Anatoly Solonitsyn, a singer who appeared in several of Tarkovsky's films, played the main role. He wrote Sardor with writer Aleksandr Misharin at the end of 1978.

Stalker, Boris Strugatsky's last film in the Soviet Union, was inspired by the brothers' book Roadside Picnic. Tarkovsky first met the brothers in 1971 and was in touch with them until his death in 1986. He wanted to film based on their book Dead Mountaineer's Hotel, but first he had to write a raw script. Influenced by a discussion with Arkady Strugatsky, he modified his strategy and started working on a Roadside Picnic script. In 1976, the first film on this film was film. The operation was mired in failure; improperly applied of the negatives had destroyed all the exterior shots. Tarkovsky's friendship with cinematographer Georgy Rerberg deteriorated to the point where he recruited Alexander Knyazhinsky as the new first cinematographer. In addition, Tarkovsky suffered a heart attack in April 1978, which resulted in more delay. The film was made in 1979 and took home the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the Cannes Film Festival. Tarkovsky vehemently denied reports that the film was either unethical or a national allegory in a question and answer session at Edinburgh Filmhouse on February 11, 1981.

Tarkovsky began production The First Day (Russian: ерв им Dyen, based on a script written by his friend and longtime collaborator Andrei Konchalovsky). During the reign of Peter the Great, the film was set in 18th-century Russia, starring Natalya Bondarchuk and Anatoli Papanov. Tarkovsky wrote a script that was not compatible with the original script in order to get the project accepted by Goskino, omitting several scenes from the original script's critique of the Soviet Union's official atheism. After a rough cut of the film, Goskino's project was suspended after it became clear that the film did not conform to the script submitted to the censors. Tarkovsky was apparently enraged by this interruption and shattered the majority of the film.

Tarkovsky and his longtime friend Tonino Guerra shot the documentary Voyage in Time together in Italy in the summer of 1979. Tarkovsky returned to Italy in 1980 for a long trip, during which he and Guerra finished the script for the film Nostalghia. He took Polaroid photographs depicting his personal life during this period.

Tarkovsky returned to Italy in 1982 to begin shooting Nostalghia, but Mosfilm later pulled out of the project, so the Italian RAI continued to support the project. Tarkovsky produced the film in 1983 and it was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, where it received the FIPRESCI Award and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. With Robert Bresson, Tarkovsky also won a special award called Grand Prix du cinéma de création. The Soviet Union lobbied to prevent the film from winning the Palme d'Or, a fact that harmed Tarkovsky's resolve to not work in the Soviet Union again. Boris Godunov, the opera at the Royal Opera House, was on stage and choreographed by him after Cannes, according to Claudio Abbado's musical direction.

He said at a press conference in Milan on July 10, 1984, that he would not return to the Soviet Union and would remain in Western Europe. "I am not a Soviet dissident, I have no rivalry with the Soviet Government," he said, but "I would be unemployed" if he returned home. At the time, his son Andriosha was still in the Soviet Union and not allowed to leave the country. Tarkovsky was processed as a Soviet Defector at a refugee camp in Latina, Italy, with the serial number 13225/379, and officially welcomed to the West on August 28.

Tarkovsky spent the majority of 1984 making the film The Sacrifice. It was shot in 1985 in Sweden, with many of the crew members being alumni from Ingmar Bergman's films, including cinematographer Sven Nykvist. Tarkovsky's film was greatly influenced by Bergman's style.

Though The Sacrifice is about an apocalypse and impending death, hope, and potential redemption, writer/director Michal Leszczylowski follows Tarkovsky on a walk; he claims to be immortal and has no fear of dying. Tarkovsky was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer at the end of the year, which was ironically. He began therapy in Paris in January 1986 and was joined by his son, Andre Jr., who was later allowed to leave the Soviet Union. What would be Tarkovsky's last film?

The Sacrifice was on view at the Cannes Film Festival and received the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury, the FIPRESCI award, and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. The awards were won by Tarkovsky's son as he was unable to attend due to his illness.

"But now I have no energy left," Tarkovsky wrote in his last diary entry (December 15, 1986). The diaries are also known as Martyrology, and they were published in 1989 and in English in 1991.

Tarkovsky died in Paris on December 29, 1986. His funeral service was held at Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. He was buried in the Russian Cemetery in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, France, on January 3, 1987. According to the woman who saw the Angel, the inscription on his gravestone, which was built in 1994, was conceived by Tarkovsky's wife, Larisa. Larisa died in 1998 and is buried alongside her husband.

In the early 1990s, a conspiracy theory was revived in Russia, but the KGB assassinated Tarkovsky. Former KGB agents testify to Viktor Chebrikov's order to ban Tarkovsky from destroying Tarkovsky's KGB orders to curtail what the Soviet government and the KGB consider as anti-Soviet propaganda by Tarkovsky. Several memoranda that surfaced after the 1991 revolution as well as the assertion by one of Tarkovsky's doctors that his cancer did not arise from a natural cause are among the many examples.

As with Tarkovsky, his wife Larisa, and actor Anatoly Solonitsyn died from the same lung cancer as well. According to Vladimir Sharun, sound designer in Stalker, they were all poisoned by the chemical plant where they were shooting the film.