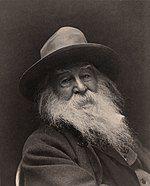

Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman was born in Long Island, New York, United States on May 31st, 1819 and is the Poet. At the age of 72, Walt Whitman biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 72 years old, Walt Whitman physical status not available right now. We will update Walt Whitman's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819-March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist.

He was a humanist who was influenced by transcendentalism and realism, adopting both views in his writings.

Whitman is one of the most influential writers in the American canon, often referred to as the father of free verse.

His poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as offensive for its overt sensuality, was controversial in its time.

Whitman's own life was scrutinized due to his suspected homosexuality. Whitman, a native of Huntington on Long Island, served as a writer, a lecturer, and a government clerk.

He left formal education at the age of 11 to go back to work.

He stayed in Brooklyn as an infant and for a large part of his career.

Leaves of Grass, Whitman's most popular piece, was first published in 1855 with his own money.

The project was an attempt to reach out to the common man with an American epic.

He continued expanding and revising it until his death in 1892.

He went to Washington, D.C., and worked in hospitals caring for the wounded during the American Civil War.

His poetry was often focused on loss and healing.

Two of his well known poems, "O Captain!

My Captain!"

On the death of Abraham Lincoln, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed" was written.Whitman moved to Camden, New Jersey, where his health worsened as a result of a stroke near the end of his life.

When he died at the age of 72, Whitman's influence on poetry was still strong.

"You cannot fully comprehend America without Walt Whitman, without Leaves of Grass," Mary Smith Whitall Costelloe said. He has said that civilization has been "up to date," as he would say, and that no scholar of history can do without him. Whitman was named "America's poet," according to Ezra Pound, a modernist poet. He is the president of the United States.

Life and work

Walter Whitman was born in West Hills, Long Island, England, on May 31, 1819, to parents with a passion in Quaker thought, Walter (1789–1855) and Louisa Van Velsor Whitman (1795–1873). He was immediately identified as "Walt" to distinguish him from his father. After American leaders, Walter Whitman Sr. named three of his seven sons after American leaders: Andrew Jackson, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. Jesse was the oldest of the Jesse family. Edward is the youngest of the couple's sixth son. Whitman and his family migrated from West Hills to Brooklyn in a string of homes at age four, partly due to poor investments. Given his family's economic hardship, Whitman reflected on his childhood as restless and unhappy. During a celebration in Brooklyn on July 4, 1825, he was lifted in the air and kissed on the cheek by the Marquis de Lafayette.

Whitman's formal education came to an end at age eleven. He later sought work for his family; he was an office boy for two lawyers and later, he was an apprentice and printer's devil for the weekly Long Island newspaper The Patriot, edited by Samuel E. Clements. Whitman learned about the printing press and typesetting. He may have written "sentimental bits" of filler text for occasional issues. When Clements and two others attempted to dig up the body of Quaker minister Elias Hicks in order to create a plaster mold of his head, the controversies became a lot of debate. Clements left the Patriot shortly afterward, perhaps as a result of the scandal.

Whitman worked with Erastus Worthington, a Brooklyn printer, during the summer. Whitman's family moved to West Hills in the spring, but Whitman stayed and took over at the shop of Alden Spooner, the leading Whig weekly newspaper in the Long-Island Star. Whitman started attending theatre performances and released some of his earliest poetry in the New-York Mirror while at the Star. Whitman, who was 16 years old at the time in May 1835, lived in the Star and Brooklyn. Whitman came to New York City to work as a compositor, but he didn't remember where he went in later years. He attempted to find more jobs, but he had a difficult time, in part due to a general recession in the 1837-panic period. He returned to his family in May 1836, now living in Hempstead, Long Island. Whitman taught intermittently at various schools until the spring of 1838, but he was not happy as a tutor.

Whitman returned to Huntington, New York, to discover his own newspaper, the Long-Islander, following his teaching experiences. Whitman served as editor, reporter, pressman, and even distributor, as well as providing home delivery. He sold the magazine to E. O. Crowell, whose first issue appeared on July 12, 1839, after ten months. There are no known living copies of the Long-Islander published under Whitman. With the Long Island Democrat, edited by James J. Brenton, he found a job as a typesetter in Jamaica, Queens, by the summer of 1839. He quit shortly after and started a new attempt at teaching from the winter of 1840 to the spring of 1841. Whitman was chased away from a teaching position in Southold, New York, 1840, according to one tale, possibly apocryphal. Whitman was allegedly tarred and feathered after a local preacher branded him a "Sodomite." Whitman's tale is likely false, according to biographer Justin Kaplan, because he went back to the town afterwards. The incident, according to biographer Jerome Loving, is a "myth." Whitman also published "Sun-Down Papers"—From the Desk of a Schoolmaster — in three newspapers between 1840 and 1841. He adopted a constructed persona in these essays, a strategy he would use throughout his career.

Whitman began working under Park Benjamin Sr. and Rufus Wilmot Griswold, then moving to New York City in May. He began as a low-level jobs at the New World. He continued working for brief stretches of time for various newspapers; in 1842, he was editor of the Aurora; in 1848 he became editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, and from 1846 to 1848 he was editor. Many of his publications were focused on music criticism, and it was during this period that he became a devoted lover of Italian opera by analyzing Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi's performances. In free verse, this new zeal had an effect on his writing. "But for the opera, I could never have written Leaves of Grass," he later said.

He contributed freelance fiction and poetry to many periodicals, including Brother Jonathan magazine edited by John Neal throughout the 1840s. Whitman lost his position at the Brooklyn Eagle in 1848 after siding with the free-soil "Barnburner" faction of the Democratic Party against the newspaper's chairman, Isaac Van Anden, who was formerly associated with the conservative, or "Hunker" faction of the party. Whitman was a delegate to the Free Soil Party's 1848 founding convention, fearing the danger of slave labor and northern businessmen as a result of slavery's arrival in the newly colonized western territories. William Lloyd Garrison, an abolitionist, derided the party's ideology as "white manism."

In 1852, he serialized Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: A History of New York in which the Reader Will Discover Some Familiar Characters In six installments of New York's The Sunday Dispatch, the reader will find some familiar faces. Whitman's pen name Mose Velsor was used in 1858 to describe a 47,000 word series called Manly Health and Training. According to reports, he drew the name Velsor from Van Velsor, his mother's maiden name. Beards, nude sunbathing, comfortable shoes, bathing regularly in cold water, eating meat almost entirely, plenty of fresh air, and getting up early each morning are all recommended in this self-help guide. Manly Health and Training "quirky," "so over the top," "a pseudoscientific tract," and "wacky," are among the present-day writers' comments.

Whitman claimed that after years of competing for "the usual prizes," he decided to become a poet. He experimented with a number of common literary styles that suited to the period's cultural tastes. He began writing Leaves of Grass, a collection of poetry that he would continue editing and revising until his death in 1850. Whitman intended to write a distinctly American epic and used free verse with a cadence based on the Bible. Whitman surprised his brothers with the first edition of Leaves of Grass, which had been produced in 1855. "I didn't think it was worth reading" in George's book.

Whitman charged for the first edition of Leaves of Grass himself and had it printed at a local print shop during breaks from commercial work. A total of 795 copies were produced. No author is given a name; rather, facing the title page was an engraved portrait by Samuel Hollyer, but 500 lines into the text read "Walt Whitman, an American, no matter whether male or female, or distinct from them; no more modest than immodest." A prose preface of 827 lines preceded the inaugural volume of poetry. The succeeding untitled twelve poems totaled 2315 lines—1336 lines from the first untitled poem, which was later titled "Song of Myself." Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote a flattering five-page letter to Whitman and told the book to colleagues, received the book's highest praise. The first edition of Leaves of Grass was widely distributed and sparked considerable interest, in part thanks to Emerson's permission, but the poetry's apparently "obscene" nature was occasionally chastised. Peter Lesley, a geologist, wrote to Emerson, calling the book "trashy, profane, and obscene" and the author "a pretentious ass." In gold leaf on the spine of the second edition, Whitman embossed a line from Emerson's letter, "I greet you at the start of a great career." "Which gave rise to the modern cover blurb in one stroke," Laura Dassow Walls, Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, wrote.

Whitman's father died on July 11, 1855, just a few days after the book Leaves of Grass was published. Critical responses began focusing more on the potentially offensive sexual themes in the months leading up to the first edition of Leaves of Grass. Despite the fact that the second edition was already printed and bound, the publisher almost didn't bother to publish it. The edition came to an end in August 1856, with 20 new poems included. Leaves of Grass were edited and re-released in 1860, 1867, and several more times during Whitman's life. Several well-known writers adored Whitman enough to return to visit him, including Amos Bronson and Henry David Thoreau.

Whitman had financial difficulties and was compelled to work as a reporter again when he first appeared in Leaves of Grass, specifically with the Daily Times in Brooklyn, beginning in May 1857. He oversaw the newspaper's contents, contributed book reviews, and wrote editorials. He left the job in 1859, but it is unknown if he was fired or wished to leave. Whitman, who often carried out detailed notebooks and journals, had no information about himself in the late 1850s.

Whitman's poem "Beat" debuted as the American Civil War was underway.Beat!

Drums!"

The North is being called to assemble in a patriotic rallying cry. George Whitman, Whitman's brother, had joined the Union army and began giving Whitman several informative letters about the battle front. A list of fallen and injured soldiers in the New-York Tribune on December 16, 1862, included "First Lieutenant G. W. Whitmore," a command that Whitman feared was a reference to his brother George. He was led south to find him right away, but his wallet was taken along the way. "Walking all day and night, unable to ride, trying to find answers, and aiming to reach big people," Whitman later wrote. George was still alive, but with only a superficial scar on his cheek. Whitman, who was greatly affected by the wounded soldiers and the piles of their amputated limbs, departed for Washington on December 28, 1862, with the intention of never returning to New York.Whitman's companion, Charley Eldridge, of Washington, D.C., aided him in gaining part-time work in the army paymaster's office, allowing Whitman to volunteer as a nurse in the army hospitals. In a book called Memoranda During the War, he will recount his experiences in "The Great Army of the Sick," which was published in a New York newspaper in 1863 and later in a book called Memoranda During the War. He then called Emerson to ask for assistance in obtaining a government job. John Trowbridge, a long-time friend, wrote a letter of suggestion from Emerson to Salmon P. Chase, Treasury Secretary of the Treasury, in the hopes that he would offer Whitman a position in the Treasury. Chase, on the other hand, did not want to recruit Leaves of Grass' author.

The Whitman family had a difficult 1864. Whitman's brother George was captured by Confederates in Virginia on September 30, 1864, and Andrew Jackson, his younger brother, died of tuberculosis compounded by alcoholism on December 3. Jesse Whitman's brother Jesse was enslaved in the Kings County Lunatic Asylum that month. Whitman's spirits were lifted again when he finally accepted a higher-paying government job in the Department of Interior as a low-grade clerk, thanks to his friend William Douglas O'Connor. On Whitman's behalf, O'Connor, a writer, daguerret, and an editor at The Saturday Evening Post, had written to William Tod Otto, the Interior Secretary, on Whitman's behalf. Whitman began his employment in 1865 on January 24, 1865, earning $1,200 per year. George was released from capture and received a furlough on February 24, 1865, despite his poor health. Whitman was promoted to a marginally better clerkship by May 1 and the publication Drum-Taps.

Whitman was fired from his career as a result of his departure from his service on June 30, 1865. Former Iowa Senator James Harlan, the current Interior Secretary, sacked him. Despite Harlan's dismissal of several clerks who "weren't at their respective desks," he may have dismissed Whitman after finding an 1860 copy of Leaves of Grass. O'Connor has protested until J. Hubley Ashton was sent to the Attorney General's office on July 1. O'Connor, though, was still furious and defended Whitman by releasing The Good Gray Poet, a biased and exaggerated biographical report, in January 1866. Whitman was portrayed as a wholesome patriot, coined his name, and his fame soared. The book "O Captain" was also assisting in his rise in fame.My Captain!

"A very traditional poem on Abraham Lincoln's death, was the only one to appear in anthologies during Whitman's lifetime."Former Confederate soldiers were interviewed for Presidential pardons as part of Whitman's work at the Attorney General's office. "There are real characters among them," he later wrote, "and you know I have a penchant for things that are out of the norm." After having trouble finding a publisher, he took a month off in August 1866 to create a new edition of Leaves of Grass, which would not be published until 1867. It was hoped that this would be the last edition. Poems of Walt Whitman was first published in England in February 1868, thanks to William Michael Rossetti's clout, with minor revisions that Whitman reluctantly accepted. The edition gained clout in England, particularly thanks to Anne Gilchrist's endorsements. In 1871, a new edition of Leaves of Grass was published, but it was mistakenly reported that the author died in a railroad accident. Although Whitman's international fame grew, he stayed at the attorney general's office until January 1872. He spent much of 1872 caring for his mother, who was now nearly eighty and suffering with arthritis. He also travelled and was invited to Dartmouth College to address the commencement address on June 26, 1872.

Whitman was compelled to move from Washington to his brother's house in Camden, New Jersey, after suffering a paralytic stroke in early 1873. His mother, who had been sick, was also present and died in May that year. Whitman's life was difficult, and he was left distraught. He stayed at his brother's house until buying his own in 1884. However, he spent the majority of his time in Camden at his brother's house on Stevens Street before buying his house. He was very active in residence and had three versions of Leaves of Grass, among other things. He was still very present in this house, having been awarded both Oscar Wilde and Thomas Eakins. Edward, his older brother who has been "invalid" since birth, lived in the house.

When his brother and sister-in-law were forced to leave due to work, he bought his own house at 328 Mickle Street (now 330 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard). For the majority of his time in Mickle Street, he was entirely bedridden. He began socializing with Mary Oakes Davis, the widow of a sea captain, during this period. She was a neighbor and boarding with a family in Bridge Avenue just a few blocks from Mickle Street. On February 24, 1885, she joined Whitman as his housekeeper in exchange for free rent. She carried a cat, a dog, two turtledoves, a canary, and other odd animals. Whitman produced further editions of Leaves of Grass in 1876, 1881, and 1889.

Whitman spent a good portion of his time in Laurel Springs, South Jersey, between 1876 and 1884, converting one of the Stafford Farm buildings to his summer home. The restored summer home has been preserved as a museum by the local historical society. In his Specimen Days article Leaves of Grass, he described the spring, creek, and lake. Laurel Lake was "the prettiest lake in either America or Europe," to him.

He produced a final edition of Leaves of Grass, a version that has been dubbed the "Deathbed Edition" as the end of 1891 approaches. "L. of G. is complete, after 33 years of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all aspects of the land, and peace & war, young and old," he wrote. Whitman, a stone mausoleum shaped like a house, was commissioned for $4,000 and visited it often during construction. "I have no relief, no escape: it is monotony—monotony—in pain—in the last week of his life."

Walt Whitman died on March 26, 1892, at his Camden, New Jersey home, at the age of 72. An autopsy revealed that his lungs had lowered to one-eight hours of normal breathing capacity as a result of bronchial pneumonia, and that an egg-shaped absces on his chest had eroded one of his ribs. "Pleurisy of the left hand, ingestion of the right lung, general military tuberculosis, and parenchymatous nephritis were among the causes of death," the author explained. In three hours, his body was on display at his Camden home; over 1,000 people attended in three hours. Because of all the flowers and wreaths left for him, Whitman's oak coffin was barely noticeable. He was buried in his tomb at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden four days after his death. At the cemetery, another public service was held, with friends delivering addresses, live music, and refreshments. The orator Robert Ingersoll, Whitman's cousin, delivered the eulogy. The remains of Whitman's parents, two of his brothers, and their families were moved to the mausoleum later.

Lifestyle and beliefs

Whitman, a vocal supporter of temperance, was not a fan of alcoholism in his youth, and he never drank alcohol in his youth. He had previously stated that he did not drink "strong alcohol" until he was 30 and occasionally called for prohibitions. Franklin Evans, also known as The Inebriate, was his first book, and it was published on November 23, 1842. Whitman wrote the book at a time when the Washingtonian movement was in vogue, as was Franklin Evans. Whitman claimed he was embarrassed by the book and called it "damned rot." He denied it by saying he wrote the book in three days solely for money while under the influence of alcohol. Despite this, he wrote several pieces promoting temperance, including The Madman and a short story "Reuben's Last Wish." Later in life, he was more liberal with alcohol, enjoying local wines and champagne.

Whitman was heavily influenced by deism. He denied that any one faith was more significant than another, and that both faiths were accepted equally. He gave an overview of major faiths and said he respected and accepted them all of them, a theme he reiterated in his poem "With Antecedents": "I believe that the old accounts, bibles, and demigod are accurate, without exception." He was encouraged to write a poem about the Spiritualism movement in 1874, but "It seems to me almost entirely a poor, cheap, crude humbug." Whitman was a skeptic, who attended all churches, but he believed in none. God was both immanent and transcendent, and the human spirit was immortal and in a state of progressive development, according to Whitman. Philosophy in the United States: He is one of many figures to take a more pantheist or pandeist stand of God by rejecting God's views as distinct from the world.

Although biographers are continuing to debunk Whitman's sexuality, he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Whitman's sexual orientation is generally based on his poetry, but this belief has been disputed. In a more subtle, individualistic way typical in American culture before the medicalization of sexuality in the late nineteenth century, his poetry depicts love and sexuality in a more subtle, individualistic way. Despite the fact that Leaves of Grass was often characterized pornographic or sexual, only one commentator suspected Whitman of "that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians" in a November 1855 review.

Whitman had close friendships with several male and boys throughout his life. Some biographers have claimed that he did not participate in sexual relationships with males, while others cite letters, journal entries, and other sources that support the sexual content of some of his relationships as proof of the sexual character of some of his relationships. John Addington Symonds, an English poet and critic, spent 20 years in correspondence trying to compel him to speak. "Do you consider the possibility of the intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and behaviors that have no doubt do exist between men in 1890," Whitman wrote to Whitman, "In your version of Comradeship." Whitman denied that his work had any such implication, saying, "[T]hat the calamus part has even allowed the possibility of such construction, as mentioned, is sad—I am embarrassed to say that even disavow'd he had fathered six illegitimate children." Some modern scholars are skeptical of Whitman's denial or the existence of the children he claimed.

Peter Doyle may be the most likable candidate for Whitman's love. Doyle, a bus conductor who Whitman encountered about 1866, and the two were inseparable for many years. Doyle said, "We were all familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood." He didn't get out at the end of the trip; in fact, he went all the way back with me." Whitman disguised Doyle's initials in his notebooks by using the code "16.4" (P.D. The alphabet's 16th and 4th letters are listed. Oscar Wilde met Whitman in the United States in 1882 and told gay rights activist George Cecil Ives that Whitman's sexual orientation was beyond doubt—"I have Walt Whitman's kiss on my lips." Whitman's sexual behavior is limited to secondhand reports. Edward Carpenter told Gavin Arthur of a sexual encounter with Whitman in 1924, the details of which Arthur wrote in his journal were unknown. When Whitman was asked outright if his "Calamus" poems were homosexual, John Addington Symonds, who later in his life, did not respond. The manuscript of Whitman's love poem "Once I Pass Through A Populous City," which was written when he was 29, shows it was about a man.

Bill Duckett, another potential lover, was also on the lookout. He lived on the same street in Camden as a youth and joined Whitman, living with him for a number of years and serving him in various capacities. At 328 Mickle Street, Duckett was 15 when Whitman bought his house. Duckett and his grandmother, Lydia Watson, were boarders on 334 Mickle Street, subletting space from another family. Duckett and Whitman met as neighbors due to their proximity. The teenagers shared Whitman's money when he had it. Whitman referred to their friendship as "thick." Although some biographers think of him as a boarder, some biographers prefer him as a lover. The poet's photograph (left) is dubbed "modeled on the traditions of a marriage portrait," as part of a series of portraits of the poet and his young male companions, as well as encrypting male-male desire. Harry Stafford, with whose family Whitman stayed at Timber Creek and whom he first met when Stafford was 18, in 1876, was yet another intense bond with a young man. Whitman's phone number was returned and re-given after a turbulent relationship spanned several years. "You know when you took it off, there was just one thing to separate it from me, and that was death," Stafford wrote to Whitman about the ring.

There are also evidence that Whitman had sexual affairs with women. In the spring of 1862, he had a romantic relationship with Ellen Grey, a New York actress, but it is not known if it was also sexual. When he moved to Camden, he had a snapshot of her decades ago, and he referred to her as "an old sweetheart of mine." "I have had six children, but two of them are dead," he wrote in a letter dated August 21, 1890. This assertion has never been verified. Towards the end of his life, he regularly told tales of previous girlfriends and sweethearts, as well as deny a New York Herald accusation that he had "never had a love affair." "The discussion of Whitman's sexual orientation will most likely continue in spite of whatever evidence emerges," Whitman biographer Jerome Loving wrote.

According to reports, Whitman liked bathing and sunbathing naked. He advised man to swim naked in Manly Health and Training, using the pseudonym Mose Velsor.In A Sun-bathed Nakedness, he wrote,

Whitman, a student of Shakespeare authorship, refused to believe in the attribution of the works of Stratford-upon-Avon's historical attribution of the works to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. Whitman's remarks about Shakespeare's historical performances in his November Boughs (1888):

Whitman, like many in the Free Soil Party who were concerned about the danger slavery would pose to free white labour and northern businessmen exploiting the newly colonized western territories, condemned slavery in the United States and praised the Wilmot Proviso. He was opposed to abolitionism at first, but later on, he felt that the campaign did more harm than good. In 1846, he wrote that the abolitionists had, in fact, slowed the progress of their cause by their "ultraism and infidiousness." Their methods jeopardized the political process, as did the Southern states' refusal to place the nation's interests above their own. "You are either to abolish slavery or it will kill you," he wrote in 1856, in his unpublished The Eighteenth Presidency, addressing the South's men. Whitman argued that even free African-Americans should not vote and was worried about the increasing number of African-Americans in the legislature, and that this increased number of African-Americans in the legislature, such as many baboons, as well as much knowledge and calibre. "What little is known about Whitman's early white supremacy in his day and place, condemning black people as servile, shiftless, ignorant, and committed to robbery," George Hutchinson and others have written, but that "despite his beliefs remaining largely unchanged, "readers of the twentieth century, including black ones," portrayed him as a fervent antiracist."

Whitman is often referred to as America's national poet, resulting in a picture of the US as a nation poet. "Although Whitman is often regarded as a champion of democracy and equality, he establishes a hierarchical system with himself at the top, America below, and the rest of the world in a subordinate position." "The Pragmatic Whitman: Reimagining American Democracy," Stephen John Mack says, "kritics, who tend to avoid it," should revisit Whitman's nationalism: "Whitman's obviously mawkish celebrations of the United States [are] one of those problematic aspects of his works that teachers and critics ignore or explain away" (xv-xvii). In an essay on "Walt Whitman's Nationalism," Nathanael O'Reilly writes "Whitman's Dream America is imperial, expansionist, hierarchical, racial, and exclusive; such an America is unacceptable to Native Americans, African-Americans, refugees, the disabled, and those who value equal rights." Whitman's nationalism dismissed concerns concerning Native Americans' treatment. "Clearly, Whitman could not consistently reconcile the United States' ingrained, even foundational, racist image of the nation with its egalitarian ideals," George Hutchinson and David Drews' essay "Racial values." He could not even comprehend such inconsistencies in his own mind."The authors concluded their essay with:

Whitman wrote in 1864 that Mexico was "the only [country] to whom we have never really done wrong" in reference to the Mexican-American War. Whitman, who was commemorating Santa Fe's 333rd birthday, argued that indigenous and Spanish-Indian elements would give the "complete American identity of the future."