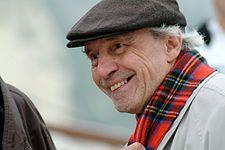

Jacques Rivette

Jacques Rivette was born in Rouen, Normandy, France on March 1st, 1928 and is the Director. At the age of 87, Jacques Rivette biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 87 years old, Jacques Rivette physical status not available right now. We will update Jacques Rivette's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Jacques Rivette (French: [livt] [Mega] [French] [French]; 1 March 1928 – 29 January 2016] was a French film producer and film critic best known for the French New Wave and film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. He made twenty-nine films, including L'amour fou (1969), Out 1 (1971), Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), and La Belle Noiseuse (1991). His work has been praised for its improvisation, loosening of plots, and long running times.

Rivette made his first short film at age 20, inspired by Jean Cocteau's decision to become a filmmaker. He moved to Paris to continue his education, attending Henri Langlois' Cinémathèque Française and other ciné-clubs; there, he met François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and other potential New Wave participants. Rivette started writing film critiques and was recruited by André Bazin for Cahiers du Cinéma in 1953. He expressed admiration for American films, particularly those of genre filmmakers like John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Nicholas Ray, as well as the nascent French cinema. Rivette's articles, which were lauded by his peers, were voted to the magazine's best and most scholarly writings, including his 1961 essay "On Abjection" and his extensive collection of interviews with film directors co-written with Truffaut. He continued making short films, including Le Coup de Berger, which is often cited as the first New Wave film. Truffaut later credited Rivette with inventing the movement.

Despite being the first New Wave director to start filming, Paris Belongs to Us was not announced until 1961, the French artists Chabrol, Truffaut, and Godard followed their own first films and popularized the movement around the world. Rivette became editor of Cahiers du Cinéma in the early 1960s and protested French censorship of his second feature film, The Nun (1966). He re-evaluated his work, establishing a distinct cinematic style with L'amour fou, which he revived. Rivette started working with large groups of actors on character growth and allowing events to occur on camera, influenced by May 68's political turmoil, improvisational theatre, and an in-depth interview with filmmaker Jean Renoir. This technology resulted in the thirteen-hour Out 1 film, which although rarely seen, is considered by cinephiles as the Holy Grail of cinephiles. Celine and Julie Go Boating's 1970s films often included fantasy and were more realistic than those of today. Rivette had a nervous breakdown and his career slowed for several years after attempting to make four straight films.

He began a business relationship with producer Martine Marignac, who produced all of his subsequent films, in the early 1980s. From then on, Rivette's output increased, and his film La Belle Noiseuse received international accolades. He resigned after finishing Around a Small Peak (2009), but Alzheimer's disease was revealed three years later. Rivette briefly married photographer and screenwriter Marilù Parolini in the early 1960s and later married Véronique Manniez, who was very private about his personal life.

Personal life

Rivette's early years in Paris were impoverished, and he was known to live ascetically on limited funds; Chabrol said he was extremely thin and hardly ate, like that of the Cheshire Cat. In an emaciated visage of a waxy pallor, Gruault described Rivette as "slight, dark-haired, and [having] a vivid dark gaze." You may also add to the look of someone who is constantly seeking to gain recognition by a society that he regarded as irremediably hostile." His opinions were highly regarded among his peers, and Douchet said, "Rivette] was the greatest talker." He was the group's unknown treasure, the occult thinker, and a tiny bit of censorship." "I might like a film so much," Godard said, "It's no good," I would comply with him," says the filmmaker, "It's no good." Truffaut said Rivette was his best friend, and the two were often seen at screenings. Truffaut said that Rivette was the only member of the organization at that time that was still capable of directing a feature film.

Rivette's relationship with Rohmer was difficult due to Rivette's involved role in bringing Rohmer down from Cahiers du Cinéma. Rivette and Rohmer respected each other, but they disagreed over Cahiers' political and aesthetic positions and financial concerns. Rohmer became close friends again after Rohmer became involved in Rivette's improvisational films, celebrating L'amour fou and appearing in Out 1. Out 1 was later described by Rohmer as "a capital monument in the history of modern cinema, a vital piece of the cinematic heritage." Rivette also adored Rohmer's films, naming Les Rendez-vous de Paris (1995) a "film of utter grace" in Paris. Several Cahiers writers during the Rohmer period, including Douchet, Jean Domarchi, Fereydoun Hoveyda, Phillippe Demonsablon, Claude Beylie and Phillippe d'Hugues, all thought him a moron if you didn't agree with him, including Claude Beylie and Phillippe D'Hugues, who said that Rivette "had a Saint-Just side" who said he was an intransigent "He figured out what was moral and right, as a hall monitor." These writers, according to Antoine de Baecque, respected Rivette but that he was "brusque, arrogant, and dogmatic" and that he "did not hesitate to excommunicate critics or mediocrities." André Labarthe and Michel Delahaye lauded him, but Delahaye praised him because he "was the most original, with a peerless charisma."

Rivette was "famous for having little or no home life," according to David Thomson, but not necessarily in a professional life that overlaps with his work. On his own, he'd rather sit in the shadow with another film; in 1956, he was described as "too aloof and forbiddingly intellectual." Rivette is a mystery in his personal life, according to Bulle Ogier: "I have no idea what he does." I only see him when we're filming" or when she bumped into him in public, but she felt she was close to him. According to Ogier, he had neuroses and phobias that often stopped him from answering the phone, and discussing his personal life would be dishonest and a betrayal. Laurence Côte said that joining Rivette's inner circle of trusted friends was difficult and that "a number of hurdles to overcome and observe codes were necessary." Rivette, according to Martine Marignac, was modest and shy, and his circle of close friends grew used to not seeing him for lengthy stretches of time. "He spends his life going to the movies, but he also enjoys listening to music." "It's clear that the world of truth assaults him." Jonathan Romney said in the 1970s, "Rivette occasionally went AWOL from his own shootings," he'd be found in one of the Left Bank art cinemas. Jean-Pierre Léaud, who referred to Rivette as a close friend, said he was the only one who saw everything in a film. And he brought everything he saw to us, including marching our own aesthetic ideals. The director was the subject of a 1990 documentary film titled Jacques Rivette, the Night Watchman, starring Claire Denis and Serge Daney. Travis Mackenzie Hoover said that the film depicts Rivette with "lonerish tendencies" and as "a sort of transient without a home or country, wandering about or loitering in public space rather than laying out some personal terra firma."

Chronique d'un été, a 1960 film starring Marilù Parolini, appeared briefly in Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin's cinéma-vérité film Chronique d'un être. Parolini was a secretary at Cahiers and later, an on-set still photographer for Rivette and other New Wave filmmakers. She and Rivette married, but soon after the stage version of The Nun closed and they eventually divorced. Parolini and Duelle, Noroît, Love on the Ground co-writer, and photographer Julie Go Boating followed them on the sets of The Nun and Celine and Julie Go Boating for a professional relationship; she continued to collaborate with Rivette on L'amour fou, Duelle, Noroît, and Love on the Ground as a co-writer, and she photographed the Nun and Celine and Julie Go Boating. Parolini died in Italy on April 21, 2012.

Rivette died of Alzheimer's disease, according to film critic David Ehrenstein on April 20, 2012. Bonitzer and Marignac later said he started feeling the disease's effects during a poor start to filming 36 vues du pic Saint-Loup. Shooting days were four hours on average, and Rivette often lost track of what had already been shot, which resulted in a shorter running time than his previous films. Rivette's second wife, Veronique Manniez, married him in the mid-2000s. They married soon after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. "Thanks to her, he avoided hospitals and was able to stay home," Marignac said. Rivette and his wife lived in the Rue Cassette neighborhood of Paris, where caregivers and doctors attended him for the last eight years of his life.