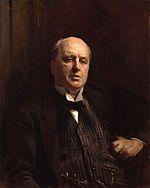

Henry James

Henry James was born in New York City, New York, United States on April 15th, 1843 and is the Novelist. At the age of 72, Henry James biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 72 years old, Henry James physical status not available right now. We will update Henry James's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Henry James (1843-04-15), 1916-02-28)28 February 1916) was an American-British author who was widely regarded as one of the best novelists in the English language by many.

He was the son of Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist William James and diarist Alice James. He is best known for a series of books dealing with the cultural and marital interplay between emigration Americans, English people, and continental Europeans.

The Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors, and The Wings of the Dove are two examples of such books.

His later experiments were more experimental.

James used a style in which ambiguous or contradictory motives and appearances were often described in describing a character's internal states of mind and social dynamics.

His late works have been compared to impressionist painting due to their ambiguity and other aspects of their composition. His novella The Turn of the Screw has earned a reputation as the most analyzed and ambiguous ghost tale in the English language, and it remains his most popular adaptation in other media.

He wrote a number of other well-regarded ghost stories and is regarded as one of the industry's best masters.

James wrote and published articles and books on critique, travel, biography, autobiography, and plays.

James, a young man from the United States, migrated to Europe as a young man and then settled in England, becoming a British subject in 1915, a year before his death.

In 1911, 1912, and 1916, James was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Life

On April 15, 1843, James was born at 21 Washington Place in New York City. Mary Walsh and Henry James, Sr., were both educated and steadfastly congenial. He was a lecturer and scholar who had inherited autonomous funds from his father, an Albany banker, and investor. Mary came from a wealthy family who had long settled in New York City. Katherine spent a lengthy time with her adult cousin. Henry, Jr. was one of four boys, the others being William, who was one year old, and younger brothers Wilkinson (Wilkie) and Robertson. Alice was his younger sister. Both of his parents were of Irish and Scottish descent.

Before he was a year old, his father sold the Washington Place home and moved the family to Europe, where they spent a time in a cottage in Windsor Great Park, England. Henry lived in Albany, New York, in 1845, and he spent the majority of his childhood between his paternal grandparents' house and a house on 14th Street in Manhattan. His father's intention was to expose him to many influences, chiefly scientific and philosophical; Percy Lubbock, the editor of his chosen letters, characterized it as "extraordinarily haphazard and promiscuous." James did not have the same education in Latin and Greek classics as the common ones. According to the father's current passions and publishing ventures, the James family travelled to London, Paris, Geneva, Boulogne-sur-Mer, and Newport, Rhode Island between 1855 and 1860, as funds were scarce in the United States. While the family travelled in Europe, Henry concentrated mainly with tutors and attended schools for a short time. Their longest stays were in France, where Henry began to feel at home and became fluent in French. He had a stutter, which seems to have appeared only when he spoke French; in French, he did not stutter; in French, he did not stutter.

The family migrated to Newport in 1860. Henry was introduced to French literature, and in particular to Balzac. Balzac was later named his "greatest master" and said he had learned more about fiction from him than from anyone else.

When fighting a fire in the fall of 1861, James suffered a back injury, most likely to his back. This injury, which resurfaced at various times during his life, rendered him unfit for military service in the American Civil War.

In 1864, the James family moved to Boston, Massachusetts, to be near William, who had enrolled first in the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard and later in the medical school. Henry was accepted into Harvard Law School in 1862, but he soon realized that he was not interested in learning law. He pursued his literary career and became acquainted with writers and commentators William Dean Howells and Charles Eliot Norton in Boston and Cambridge, as well as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the future Supreme Court justice, and his first academic mentors, James T. Fields and Annie Adams Fields.

"Miss Maggie Mitchell in Fanchon the Cricket," his first published work was a study of a stage performance. About a year later, "A Tragedy of Error," his first short story, was released anonymously. The first payment was made for Sir Walter Scott's books, written for the North American Review. Fields, the editor of The Nation and Atlantic Monthly, wrote fiction and nonfiction pieces for The Nation and Atlantic Monthly, where Fields was editor. Watch and Ward, his first book, was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1871. In 1878, the novel was published in book form for the first time.

He met John Ruskin, Charles Dickens, Matthew Arnold, William Morris, and George Eliot during a 14-month tour around Europe in 1869–70. Rome impacted him greatly. To his brother William, he wrote, "Here I am now in the Eternal City.""At last—for the first time—I live!"

He began to support himself as a freelance writer in Rome and then went on to serve as the New York Tribune's Paris reporter, thanks to the influence of its editor, John Hay. When these attempts went wrong, he returned to New York City. He published Transatlantic Sketches, A Passionate Pilgrim, and Roderick Hudson between 1874 and 1875. Nathaniel Hawthorne influenced him during his early years as a student.He departed for Paris in 1875 and by 1876, he landed in London, where he continued to work with Macmillan and other publishers who paid for serial installments that were not published in book form. The audience for these serialized novels was mainly made up of middle-class women, and James failed to produce meaningful literary work within the constraints placed by editors' and publishers' expectations of what was appropriate for young women to read. He lived in rented rooms, but he was able to join gentlemen's clubs that had libraries and where he could entertain male friends. Henry Adams and Charles Milnes Gaskell introduced him to English life, the latter introducing him to the Travellers' and the Reform Clubs. He was also an honorary member of the Savile Club, St James' Club, and the Athenaeum Club began in 1882.

He migrated to the Latin Quarter of Paris in the fall of 1875. He spent the next three decades — the majority of his life — in Europe, aside from two trips to America. He met Zola, Daudet, Maupassant, Turgenev, and others in Paris. He stayed in Paris for a year before heading to London.

He met with the leading figures of politics and culture in England. He continued to write, publishing The American (1878), a sequel to Watch and Ward (1878), French Poets and Novelists (1878), Hawthorne (1879), and several short works of fiction. Daisy Miller made his name on both directions of the Atlantic in 1878. It attracted attention in large part because it depicted a woman whose behavior is outside of Europe's social norms. The Portrait of a Lady, which appeared in 1881, is also his first work, The Portrait of a Lady.

He first visited Wenlock Abbey in Shropshire, home of his friend Charles Milnes Gaskell, whom he had met through Henry Adams in 1877. The lake in The Turn of the Screw was heavily inspired by the darkly romantic abbey and the immediate countryside that were included in his essay "Abbeys and Castles."

When living in London, James continued to track the careers of the French realists, particularly Émile Zola. Their stylistic practices influenced his own work in the years to come. Hawthorne's influence on him dwindled during this period, being replaced by George Eliot and Ivan Turgenev. The Europeans, Washington Square, Confidence, and The Portrait of a Lady appeared in 1878 to 1881.

Several deaths were recorded during the 1882 to 1883 period. While James was in Washington, DC, on an extended visit to America, his mother died in January 1882. For the first time in 15 years, he returned to his parents' house in Cambridge, where he was joined by all four of his siblings. He returned to Europe in mid-1882, but by the year's end, he was back in America. Emerson, a long family friend, died in 1882. Both Wilkie and his companion Turgenev died in 1883.

In 1884, James made another trip to Paris, where he saw Zola, Daudet, and Goncourt again. He had been following the careers of French "realist" or "naturalist" writers, and was increasingly influenced by them. He published The Bostonians and The Princess Casamassima in 1886, both of whom were heavily influenced by the French writers and who had assiduously studied. Critical reaction and sales were poor. He told Howells that the books had affected his career rather than helped because they had "reduced the desire and demand for my books to zero." The Tragic Muse, his third book from the 1880s, was The Tragic Muse. Although he was following Zola's precepts in his books of the 1980s, their tone and attitude are closer to Alphonse Daudet's. His novels' lack of critical and financial stability during this period led him to write for the theatre; his dramatic works and his theatre experiences are discussed below.

"For pure and copious lucre," he began translating Port Tarascon, the third volume of Daudet's adventures of Tartarin de Tarascon, in the 1889 quarter. This translation, which The Spectator has praised as "clever" by The Spectator, was published in Harper's Monthly in January 1890 by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

James was in danger after Guy Domville's appearance in 1895, and thoughts of death plagued him. His depression was exacerbated by the deaths of those close to him, including Alice in 1892; his cousin Wolcott Balestier in 1891; and Stevenson and Fenimore Woolson in 1894. Fenimore Woolson's sudden death in January 1894, as well as the subsequent debate surrounding her death, were terribly sad for him. "The repercussions of Fenimore Woolson's death, according to Leon Edel, "we can detect a strong degree of guilt and bewilderment in his letters, and even more in those rare tales of the next half-dozen years, "The Beast in the Jungle" and "The Beast in the Jungle."

The years of dramatic work were not lost. As he entered the last stage of his career, he found ways to bring dramatic techniques to a novel form. James made several trips around Europe in the late 1880s and 1890s. In 1887, he spent a long time in Italy. He wrote the short story The Aspern Papers and The Reverberator in the same year.

He went to Rye, Sussex, and wrote The Turn of the Screw, 1897–1900; The Awkward Age and The Sacred Fount appeared in 1897–1900. He wrote The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove, and The Golden Bowl from 1902 to 1904.

He returned to America and spoke about Balzac in 1904. He published The American Scene and edited the "New York Edition," a 24-volume series of his drawings from 1906 to 1910. William's brother William died in 1910 in the United States after a failed search for freedom in Europe on what turned out to be his (Henry's) last visit to the US (from summer 1910 to July 1911) and was near him, according to a letter he wrote when he died.

He wrote A Small Boy and Others in 1913 and Notes of a Son and Brother. He did war service in 1914, during the outbreak of the First World War. He became a British citizen in 1915 and was given the Order of Merit the following year. He died in Chelsea, London, on February 28, 1916, and at Golders Green Crematorium, he was cremated. His ashes were buried in Cambridge Cemetery, Massachusetts, as he requested.

James consistently denied rumors that he should marry, and after settling in London, he declared himself "a bachelor." In many books on the James family, F. W. Dupee advanced the belief that he was in love with his cousin, Mary ("Minnie") Temple, but that a neurotic fear of sex discouraged him from revealing such affections: "James' invalidity "was actually the product of some fear of or scramble against sexual affections on his part." Dupee exemplified James' romanticism about Europe, a Napoleonic fantasy into which he fled, with a tale from James' memoir, A Small Boy and Others, recounting a desire for a Napoleonic portrait in the Louvre.

Leon Edel wrote a huge five-volume biography of James, which used unpublished letters and records after Edel obtained James' family's permission. Edel's portrayal of James included the suggestion that he was celibate, a position first advanced by critic Saul Rosenzweig in 1943. Sheldon M. Novick published Henry James: The Young Master in 1996, followed by Henry James: The Mature Master (2005). "The first book sparked some of an outrage in Jamesian circles" because it challenged the old learned notion of celibacy, a once-familiar model in biographies of homosexuals, where direct evidence was nonexistent. "As a kind of failure," Novick criticized Edel for following the discounted Freudian interpretation of homosexuality "as a kind of failure." The difference of opinion emerged in a series of conversations between Edel (and later Fred Kaplan filling in for Edel) and Novick that were published by the online magazine Slate, with Novick arguing that even the mention of celibacy went against James' own injunction "live.""—not "fantasize!"

A letter written by James in old age to Hugh Walpole has been cited as an explicit statement of this. Walpole confessed to indulging in "serious jinks" while James wrote a response endorsing it: "We must know, as much as possible," yours and mine's beautiful artwork is discussed — and the only way to figure it out is to have lived and loved & mourned — not regret a single "excess" of my responsive youth.

Other scholars have investigated James' interpretation of him as leading a less austere emotional life. The often political history of Jamesian scholarship has also been investigated. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet made a monumental contribution to Jamesian scholarship by arguing that he should be read as a gay writer whose desire to keep his sexuality a mystery, according to author Colm Tóibn's layered style and dramatic artistry. According to Tóibn, such a reading "removed James from the realm of dead white males who wrote about posh people." "He's become our new guy."

The letters from James to expatriate American sculptor Hendrik Christian Andersen have drew particular notice. In 1899, James met Andersen, the 27-year-old boy, who wrote letters to Andersen that are eerily personal: "I hold you, dearest boy, in my deepest passion, and count on your feeling me—in every throb of your soul." Even though he was a sexagenarian Henry, James referred to himself as "always your hopelessly celibate." Although James' biographers disagreed on how accurate the description was, the letters to Andersen were sometimes reminiscent of "our dear boy, my arm around you": "I put the pulsation of our superb future and your laudable endowment."

His numerous letters to the numerous young homosexual men in his close male friends are becoming more forthcoming. James might write: "I repeat, almost to indiscretion, that I could live with you." In comparison, I can only live without you." Following a long visit, James refers jokingly to their "good little congress of two." He begins with convoluted jokes and narcotics about their marriage, referring to him as an elephant who "paws you oh so benevolently" and concerns about Walpole's "well-meaning old trunk" in letters to Hugh Walpole. Walter Berry's letters, which were published by the Black Sun Press, have long been known for their thinned outrage.

However, James corresponded in derogatory language with his numerous female colleagues, writing, for example, to fellow novelist Lucy Clifford: "Dearest Lucy!"