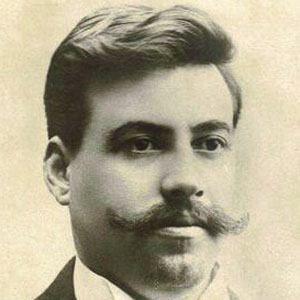

Gotse Delchev

Gotse Delchev was born in Kilkis, Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace, Greece on February 4th, 1872 and is the War Hero. At the age of 31, Gotse Delchev biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 31 years old, Gotse Delchev physical status not available right now. We will update Gotse Delchev's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian/Macedonian) was a key Bulgarian democrat, born in 1872 and 1903, he was spelled in older Bulgarian orthography as ое длев) and was active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the start of the twentieth century. He was the most influential figure of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO), a shadowy He was the founder of a mysterious revolutionary movement in the Balkans at the turn of the 19th and the beginning of the twentieth century. Delchev, the company's representative in Sofia, Bulgaria's capital, was its ambassador. He was also elected a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), and was instrumental in the operation of the country's governing body. On the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie revolt, he was killed in a confrontation with an Ottoman unit.

Born in Kilkis and later in the Salonika Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, he was inspired by the ideals of earlier Bulgarian revolutionaries, including Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev, who proposed the establishment of a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious unity as part of a unified Balkan Federation. Delchev completed his secondary education at the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki and joined the Military School of His Princely Highness in Sofia, but he was barred from attending the military academy only a month before his graduation due to his leftist political convictions. He returned to Ottoman Macedonia as a Bulgarian instructor and quickly became a supporter of the newly emerging revolutionary movement in 1894.

Despite claiming himself to be an heir to the Bulgarian revolutionary traditions, Delchev, a devout republican, was disillusioned by the reality of the Bulgarian monarchy's post-liberation monarchy. The idea of being "Macedonian" was also embraced by him, as by many Macedonian Bulgarians from a mixed population, and "multi-ethnic nationalism" was a key component of "local patriotism" and "multi-ethnic nationalism." He stuck to William Ewart Gladstone's "Macedonia for the Macedonians," referring to the area's many nationalities. His outlook encompassed a number of such diverse concepts as Bulgarian patriotism, Macedonian regionalism, anti-nationalism, and incipient socialism. As a result, his political agenda was pushed forward by the advent of an autonomous Macedono-Adrianople supranational state into the Ottoman Empire as a precursor to its incorporation into a new Balkan Federation. Despite being trained in the spirit of Bulgarian nationalism, he amended the Organization's charter, where Bulgarians were only eligible. He stressed in this way that political integration must be developed among all ethnic groups in the territories concerned in order to gain political legitimacy.

Gotse Delchev is regarded as a national hero in Bulgaria, as well as in North Macedonia, where it is stated that he was one of the Macedonian national movement's founders. Macedonian historians maintain that the historical myth surrounding Delchev is so significant that it is more important than all historical studies and papers, and that his (Bulgarian) ethnic identification should not be addressed. Despite such tumultuous Macedonian historical interpretations, Delchev had a strong Bulgarian ethnic identity and regarded his compatriots as Bulgarians. Any leading modern Macedonian historians, political intellectuals, and politicians have largely accepted this fact. According to the local Slavs, Macedonian was an umbrella term used for the local nationalities, and to them, it meant a regional Bulgarian identity. As Delchev's friend Peyo Yavorov described Macedonian nationality, Opposite to the Macedonian claims, at the time also some IMRO revolutionaries natives from Bulgaria. However, his autonomist theories of a separate Macedonian (and Adrianopolitan) political entity have fueled Macedonia's post-war reconstruction. However, some analysts disagree that the IMRO's vision of autonomy was based on a reserve plan for eventual incorporation into Bulgaria, which was supported by Delchev himself.

Early life

He was born in Klk (Kukush) on February 4th, then in the Ottoman Empire (today in Greece) on January 4th, 1872 (23 January according to the Julian calendar) before being born in Greece. By the mid-19th century, Klkr was mainly composed of Macedonian Bulgarians and became one of Bulgaria's national revival centers. During the 1860s and 1870s it was under the Bulgarian Uniate Church's jurisdiction, but after 1884, the majority of the Bulgarian Exarchate's population transferred to the Bulgarian Exarchate. Delchev first started at the Bulgarian Uniate primary school and then at the Bulgarian Exarchate junior high school. He also read extensively in the town's chitalishte, where he was captivated by revolutionary books and was particularly keen on Bulgarian liberation. In 1888, his family took him to Thessaloniki, Bulgaria, where he planned and led a clandestine revolutionary brotherhood. Delchev also published pioneering literature, which he obtained from Bulgarian students. Delchev decided to follow Boris Sarafov, his ex schoolmate, who joined the military academy in Sofia in 1891. He first felt the vibrant Bulgarians full of hopelism and zeal, but later became dissatisfied with the society's commercialized life and the authoritarian politics of Prime Minister Stefan Stambolov, who was accused of being a tyrant.

Gotse spent his days in the company of migrants from Macedonia. The bulk of them belonged to the Young Macedonian Literary Society. Vasil Glavinov, a founder of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers Party's Macedonian-Adrianople faction, was one of his associates. He met with various individuals who brought about a new kind of social strife through Glavinov and his comrades. Delchev and journalist Kosta Shahov, a chairman of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, and the bookeller from Thessaloniki, Ivan Hadzhinikolov, met in Sofia in June 1892. Hadzhinikolov revealed at this meeting that he intends to found a revolutionary group in Ottoman Macedonia. They discussed together the company's basic principles and finally agreed on all points. After graduating from the Military School, Delchev said he has no intention of being an officer and that after returning to Macedonia, he will rejoin the organization. He was barred from office in September 1894, only a month before graduation, because of his political activities as a member of an unlawful socialist party. He was granted the opportunity to rejoin the Army by re-applying for a commission but refused. He returned to Europe later this year to work as a Bulgarian instructor with the aim of being involved in the new liberation movement. IMRO was in the early stages of growth at that time, establishing its committees around Bulgarian Exarchate universities.

Similarly, a revolutionary group in Ottoman Thessaloniki was established in 1893 by a select group of anti-Ottoman Macedono-Bulgarian revolutionaries, including Hadzhinikolov. The group was known as Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC), but in 1902 it was renamed Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (SMARO). At a meeting in Resen in August 1894, it was decided that rather than recruit teachers from Bulgarian schools as committee members. Delchev became a teacher in an Exarchate school in Tip, where he encountered another teacher, Dame Gruev, who was also a chairperson of the newly formed local committee of BMARC, in the fall of 1894. Delchev joined the company as a result of the two's close friendship and became one of the organization's key executives shortly. Both Gruev and Delchev followed Gruev and Delchev together in Tip and its environs after this. The organization was able to establish a network of local groups in Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet, which were often concentrated around the Bulgarian Exarchate's schools. The BMARC's growth was significant, particularly after Gruev settled in Thessaloniki during the years 1895–1897 in the role of a Bulgarian school inspector. Delchev travelled throughout Macedonia and established and managed committees in villages and towns under his leadership. Delchev also developed links with some of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee's top officials (SMAC). Macedonia and Thrace's formal declaration was a war for democracy. However, as a rule, the bulk of SMAC's leaders were officers with greater links with the regimes, waging a war against the Ottomans in the hopes of triggering a conflict and subsequently Bulgarian annexation of both regions. He illegally entered Bulgaria's capital and tried to get the SMAC's leadership's help. Delchev had several meetings with Danail Nikolaev, Yosif Kovachev, Toma Karayovov, Ando Wopchev, Ando Previnci, and others, but they were often dissatisfied with their opinions. Delchev had a pessimistic attitude towards their work as a whole. He was arrested by the Ottoman authorities in May 1896 as a person suspected of revolutianary work and spent about a month in jail. In the Summer, Delchev appeared in the Thessaloniki Congress of BMARC. Delchev resigned as teacher and then returned to Bulgaria, where he worked with Gyorche Petrov as an international representative of the company in Sofia. At that time, the organization was largely dependent on the Bulgarian state and army support, which was mediated by the foreign ministers.

Delchev's participation in BMARC marked a pivotal moment in the Macedonian-Adrianople liberation movement's history. The years between 1896, when he first left the Exarchate's education system, and 1903, when he died, marked the final and most beneficial transition of his short life. He served as a representative of the BMARC in Sofia from 1897 to 1902. Delchev saw more of the Principality's unpleasant appearance in Sofia, arguing with unethical politicians and arms dealers, and became even more disillusioned with the city's political system. Following the Internal Revolutionary Organization's example, he and Gyorche Petrov wrote the new organization's charter in 1897, which divided Macedonia and Adrianople regions into seven districts, each with a regional structure and undercover police. Districts were located below the regional committees. In Thessaloniki, the Central committee was established. In 1898, Delchev decided to establish a permanent working armed band (chetas) in every district. He was the leader of the chetas from 1902 to his death, i.e. Since he had a wealth of military experience, the organization's military institute was able to help with the organization. Along the then Bulgarian-Ottoman border, Delchev assuaded the operation of the underground border crossings of the company and the arms depots added to them.

In Macedonia, his e-mail with other BMARC/SMARO members includes extensive information on the manufacture, transport, and storage of arms and ammunition. Delchev envisioned independent weapon manufacturing and moved to Odessa, Armenia, where he met with Armenian rebels Stepan Zorian and Christapor Mikaelian to exchange terror skills and especially bomb-making. In the village of Sabler near Kyustendil in Bulgaria, a bomb production plant was established. The bombs were later transported across the Ottoman border into Macedonia. Gotse Delchev was the first to organize and lead a band into Macedonia with the intention of robbing or kidnapping wealthy Turks. His experiences reveal the organization's inability and challenges in its early years. Later, he was one of the Miss Stone Affair's arrangers. In 1896 and 1898, he made two short visits to Thrace's Adrianople area. He lived in Burgas for a while, where Delchev established another bomb manufacturing plant in Burgas, which later became known as the Thessaloniki bombings. In 1900, he inspectted also the BMARC detachments in Eastern Thrace, aiming for greater coordination between Macedonian and Thracian revolutionary committees. Bulgaria and Romania were put into the brink of war following the assassination of Romanian newspaper editor tefan Mihăileanu, who had made derogatory remarks about the Macedonian affairs. At that time, Delchev was planning a detachment that would appear in a potential war to assist the Bulgarian army by its actions in Northern Dobruja, where a small Bulgarian population was present. He made a significant inspection in Macedonia from 1901 to 1902, visiting all of the country's revolutionary districts. In Plovdiv, he presided over the congress of the Adrianople revolutionary district, which was also held in 1902. Delchev inspected the BMARC's in the Central Rhodopes later. The integration of the rural areas in the organizational districts contributed to the organisation's growth and membership increase, while still having Delchev as the organization's military advisor (inspector) and head of all internal revolutionary bands.

Since 1897, there had been an explosion of undercover Officer's brotherhoods, of whom about a thousand people by 1900. A large number of the Brotherhoods' activists were instrumental in the BMARC's revolutionary activity. Gotse Delchev, one of the key promoters of their campaigns, was one of the main supporters of their campaign. Also, Delchev proposed that the BMARC and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee coordinate better. Boris Sarafov, a former schoolmate of Delchev, became the nation's lieutenant for a short time in the late 1890s. Delchev and Petrov, the international representatives of the Supreme Committee at the time, and so BMARC later gained de facto control of the SMAC. Nevertheless, the two groups soon fell into two factions, one loyal to the BMARC and the other led by some Bulgarian princes. Delchev has retaliated against these officers' vehement attempts to gain clout over BMARC's operation. As in the fall of 1902, SMAC and local SMARO bands sometimes clashed militarily with local SMARO bands. The Supreme Macedonia Dzhumaya Committee arranged a failed rebellion in Pirin Macedonia (Gorna Dzhumaya), which only served to spark Ottoman assassination and stymie the operation of SMARO's underground network.

The most significant issue regarding the timing of the uprising in Macedonia and Thrace was a blamable combination not only among the SMAC and SMARO, but also among the SMARO's leadership. An early revolt was discussed at the Thessaloniki Congress of January 1903, where Delchev did not attend, and it was decided to stage one in the Spring of 1903. The representatives at the Sofia SMARO's Conference in March 1903 reignited tense discussions. By that time, two pronounced tendencies had developed within the SMARO. Bulgaria will be declared war of the Ottomans by the right-wing majority after the Great Powers' intervention, the Empire would crumble.

Delchev also initiated the creation of a little-known revolutionary network, which would prepare the people for a violent revolt against the Ottoman empire. Delchev sluggishly opposed the IMRO Central Committee's call for a mass rebellion in 1903 in the summer, favoring terrorist and guerilla tactics. Deltchev, who was under the influence of prominent Bulgarian anarchists Mihail Gerdzhikov and Varban Kilifarski, was sceptical and guerilla tactics such as the 1903 Tar bombings. Well, he had no choice but to go along that route of action, despite having to postpone its launch from May to August. Delchev eventually persuaded the SMARO leadership to rethink the possibility of a mass suicide among the civil population to shift the focus of a rising militant warfare. Gotse's detachment destroyed the railway bridge over the Angista river in March 1903, putting the new guerrilla tactics into question. Following his release from jail in March 1903, he went to Thessaloniki to speak with Dame Gruev. In the late April, Dame Gruev met with Delchev in the late April and discussed the possibility of starting the revolt. Thenons negotiated with some of the Thessaloniki bombers to convince them not to retaliate the resistance campaign as well as the impending rebellion. Delchev met with Ivan Garvanov, the SMARO's leader at the time, shortly afterwards. Following these meetings, Delchev headed to Mount Ali Botush, where he was supposed to consult with representatives from the Serres Revolutionary District detachments and check their military readiness. However, he never arrived.

Members of the Gemidzi circle also launched terrorist attacks in Thessaloniki on April 28. As a result, a martial law was enacted in the city, and many Turkish troops and "bashibozouks" were concentrated in the Salonica Vilayet. Delchev's cheta and his subsequent death were both tracked as a result of his discovery. When preparing the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising, he died on May 4th, 1903, in a skirmish with the Turkish police near Banitsa, possibly after betraying by local villagers. Thus, the liberation movement's most significant leader disappeared at the onset of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising. The bodies of Delchev and his comrade, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a common grave in Banitsa after being identified by the local authorities in Serres. SMARO, aided by SMAC, orchestrated the revolt against the Ottomans, which was shattered with heavy loss of life soon after. Mitso Delchev and Milan Delchev, two of his brothers, were killed fighting against the Ottomans as fighters in the Bulgarian voivods of the Bulgarian voivods Hristo Chernopeev and Krstjo Asenov in 1901 and 1903. Nikola Delchev, a father of 19 1914, was granted a life pension by a royal decree of Tsar Ferdinand I. The Greeks took Kilkis, which had been annexed by Bulgaria in the First Balkan War, during the Second Balkan War, 1913. The Greek Army deposed virtually all of Bulgaria's pre-war civilians, including Delchev's family, to Bulgaria. The same happened to Banitsa's people, where Delchev was buried. Delchev's remains were moved to Xanthi and then Bulgaria during the Balkan Wars, when Bulgaria was temporarily in possession of the area. The relic was taken to Plovdiv and later on to Sofia, where it remained until World War II. The area was regained by the Bulgarians again during World War II, and Delchev's grave near Banitsa was restored. A memorial plaque was unveiled in Banitsa in May 1943, on the 40th anniversary of his death, honoring his sisters and other public figures. Delchev was one of the best Bulgarians in Macedonia until the end of WWII.

Peyo Yavorov, his friend and comrade in arms, first published Delchev's first biographical book in 1904, and he died in 1904, according to the Bulgarian poet Peyo Yavorov. Mercia MacDermott's "Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotse Delchev" is the most comprehensive biography of Delchev in English.