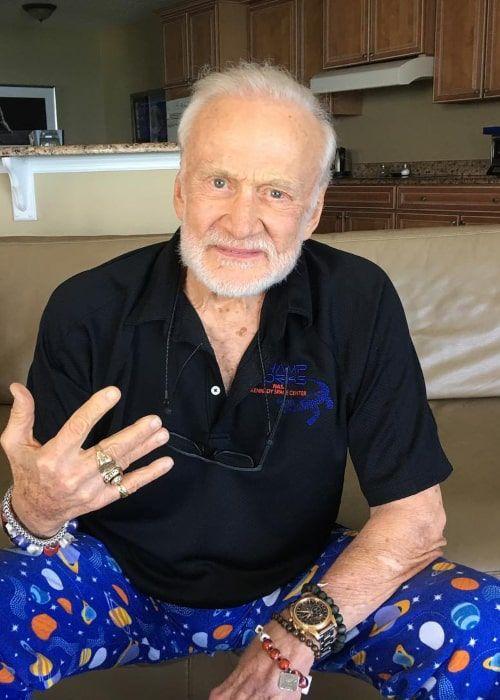

Buzz Aldrin

Buzz Aldrin was born in Glen Ridge, Essex County, New Jersey, United States on January 20th, 1930 and is the Astronaut. At the age of 94, Buzz Aldrin biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 94 years old, Buzz Aldrin has this physical status:

Buzz Aldrin (born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr.) is an American engineer and a former fighter pilot and explorer.

Aldrin flew three spacewalks as pilot of the 1966 Apollo 12 mission and Mission Commander Neil Armstrong were the first two humans to land on the Moon. Aldrin, a student at the United States Military Academy in West Point, graduated third in the class of 1951 with a degree in mechanical engineering.

He was recruited into the US Air Force and served as a jet fighter pilot during the Korean War.

He carried out 66 combat missions and shot down two MiG-15 aircraft. After receiving a Sc.D. degree, I decided against doing a Sc.E. Aldrin was chosen as a member of NASA's Astronaut Group 3, making him the first explorer with a doctoral degree.

His doctoral dissertation was Line-of-Sight Guidance Technologies for Manned Orbital Rendezvous, earning him the nickname "Dr. Norm."

Fellow explorers join Rendezvous.

On Gemini 12, his first space flight was in 1966, during which he spent more than five hours on extravehicular activity.

Aldrin touched the Moon at 03:15:16 on July 21, 1969 (UTC), nineteen minutes after Armstrong touched the surface, three years later, while command module pilot Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit.

When Aldrin privately took communion, he became the first one to host a religious service on the Moon. He joined the United States Air Force Test Pilot School after leaving NASA in 1971.

After 21 years of service, he retired from the Air Force in 1972.

Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009) chronicle his attempts with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years after leaving NASA.

He continued to advocate for space exploration, particularly a human mission to Mars, and created the Aldrin cycler, a unique spacecraft route that makes travel to Mars more accessible in terms of time and propellant.

He has been inducted into several Halls of Fame, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, and is included in numerous Halls of Fame.

Early life

Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. was born on January 20, 1930 at Glen Ridge, New Jersey, and was admitted to Mountainside Hospital. Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr. and Marion Aldrin (née Moon) grew up in Montclair, Montclair. His father served in the Army during World War I and as the assistant commandant of the Army's certification program at McCook Field, Ohio, from 1919 to 1922, but he left the Army in 1928 and became an executive at Standard Oil. Madeleine, who was four years older, and Fay Ann, who was a year and a half older, Aldrin had two sisters: Madeleine, who was four years older, and Fay Ann, who was a year and a half older. His name, which became his legal first name in 1988, emerged as a result of Fay's mispronouncing "brother" as "buzzer," which was later shortened to "Buzz." He was a Boy Scout, with the rank of Tenderfoot Scout.

Aldrin did well in school, earning an A average. He played football and was the starting center for Montclair High School's undefeated 1946 state champion squad. His father wanted him to attend the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and enrolled him in Severn School, a preparatory school for Annapolis, who also gave him a Naval Academy appointment from Albert W. Hawkes, one of New Jersey's youngest senators. Aldrin attended Severn School in 1946 but had no plans about his future. He was sick of seasickness and considered ships a distraction from flying planes. At West Point, New York, he confronted his father and told him not to compel Hawkes to change the nomination to the United States Military Academy.

In 1947, Aldrin arrived in West Point. He did well academically, finishing first in his class this year (first) year. Aldrin was also an excellent athlete, competing in pole vault for the academy track and field team. In 1950, he accompanied a group of West Point cadets to Japan and the Philippines to investigate Douglas MacArthur's military government policies. The Korean War broke out during the journey. Aldrin, a bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering, ranked third in the class of 1951 on June 5, 1951.

Personal life

Aldrin has been married three times. Joan Archer, a Rutgers University and Columbia University alumna with a master's degree, was his first marriage. They had three children, James, Janice, and Andrew. They applied for divorce in 1974. Beverly Van Zile, whom he married on December 31, 1975, and divorced in 1978, was his second. Lois Driggs Cannon, who married on February 14, 1988, was his third child. In December 2012, the couple's divorce was finalized. The deal included 5 percent of their $475,000 bank account and $9,500 per month, which was less than 30 percent of his annual income, which was estimated at more than $600,000. Jeffrey Schuss, his son Janice's son, has three great-grandsons, and one grandchild.

Aldrin was involved in a court fight with his children Andrew and Janice, as well as former business manager Christina Korp, alleging that he was physically impaired by dementia and Alzheimer's disease in 2018. His children pleaded for his children's discovery that he had new relatives who were alienating him from the family and urging him to invest his money at a high rate. They wanted to be named legal guardians so they could control his money. Aldrin filed a lawsuit against Andrew, Janice, Korp, and the family's companies and foundations. Aldrin argued that Janice was not acting in his financial interests and that Korp was exploiting the elderly. He attempted to take over Aldrin's social media pages, finances, and companies. He pleaded with his children in March 2019 just months before the Apollo 11 mission's 50th anniversary.

Aldrin is a vocal advocate for the Republican Party, coordinating fundraisers for its members of Congress and assisting candidates. He appeared at a rally for George W. Bush in 2004 and campaigned for Paul Rancatore in Florida in 2008. Mead Treadwell in Alaska in 2014 and Dan Crenshaw in Texas in 2018. As a guest of President Donald Trump, he attended the 2019 State of the Union Address as a guest.

Aldrin said he was a fan of Apollo 11 colleague Neil Armstrong's death in 2012, and he was devastated.

Aldrin revealed to Time magazine that he had just undergone a facelift, boasting that the g-forces he was exposed to in space "caused a sagging jowl that needed some attention." He mainly lived in Beverly Hills and Laguna Beach, including Emerald Bay and Beverly Hills. He sold his Westwood condo following his third divorce. He also lives in Satellite Beach, Florida.

Military career

Aldrin was ranked among the best students in his class for his choice of assignments. He chose the United States Air Force, which had remained separate from Aldrin in 1947 when the West Point Air Force was still at West Point and did not have its own academy. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and underwent basic flight instruction in T-6 Texans at Bartow Air Base in Florida. Sam Johnson, who later became a prisoner of war in Vietnam, was one of his classmates; the two became best friends. Aldrin attempted a double Immelmann turn in a T-28 Trojan at one point, but he lost a grayout. He recovered in time to pull out at 200 feet (61 m), preventing what might have been a deadly accident.

When Aldrin was deciding which kind of plane he should fly, his father advised him to choose bombers because command of a bomber crew gave him the opportunity to learn and hone leadership skills, which may have a better chance for promotion. Aldrin preferred rather to fly fighters instead. He retired to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, where he learned to fly the F-80 Shooting Star and the F-86 Sabre. He preferred the latter over the former jet fighter pilots of the time.

Aldrin was assigned to the 16th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, which was part of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, in December 1952. At the time, it was based at Suwon Air Base, about 20 miles (32 km) south of Seoul, and it was involved in combat operations as part of the Korean War. His main fuel system froze at 100 percent power during an acclimatization flight, and he'd have shortly used up all his fuel. He was able to overrule the settings manually, but doing so required pressing a button down, which made it impossible to use his radio. He barely made it back under obscene radio silence. He flew 66 combat missions in F-86 Sabres in Korea, and shot down two MiG-15 aircraft.

On May 14, 1953, he fired the first MiG-15, which was on May 14, 1953. Aldrin was flying about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Yalu River when he encountered two MiG-15 fighters below him. Aldrin opened fire on one of the MiGs, whose pilot may never have noticed him approaching. The pilot ejecting from his damaged aircraft was captured by Aldrin in the June 8, 1953 issue of Life magazine.

Aldrin's second aerial victory came on June 4, 1953, when he led an aircraft from the 39th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron in a strike in North Korea on an airbase. They were quicker than his older aircraft, but they had a difficult time keeping up. A MiG was then seen approaching from above. This time, Aldrin and his foetus met at the same time. They were attempting to get to the other through a series of scissor maneuvers, trying to get behind the others. Aldrin was the first to do so, but his gun sight jammed. He then manually sighted his weapon and fired. He had to pull out because the two aircraft were too low for the dogfight to continue. The MiG's canopy opened and the pilot eject, but Aldrin was uncertain if there was ample time for a parachute to open. He was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals for his service in Korea.

Aldrin's year-long tour ended in December 1953, by which time the war in Korea had come to an end. At Nellis, Aldrin was hired as an aerial gunnery instructor. In December 1954, he became an aide-de-camp for Brigadier General Don Z. Zimmerman, the Dean of Faculty at the nascent United States Air Force Academy, which opened in 1955. He graduated from the Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama the same year. He flew F-100 Super Sabres with nuclear weapons from 1956 to 1959, as the 22nd Fighter Squadron's 36th Fighter Wing, based at Bitburg Air Base in West Germany. Ed White, who had been a year behind him at West Point, was one of his squadron colleagues. After White left West Germany to study for a master's degree in aeronautical engineering at the University of Michigan, he wrote to Aldrin, asking him to do the same.

Aldrin enrolled as a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1959 in the hopes of earning a master's degree through the Air Force Institute of Technology (MIT). Richard Battin was the instructor for his astrodynamics class. David Scott and Edgar Mitchell, two other USAF soldiers who later became astronauts, followed the course around this time. Charles Duke, another USAF officer, followed the course and earned his 1964 master's degree at MIT under Laurence R. Young's guidance.

Aldrin loved the classes but decided not to pursue a doctorate instead. He received a Sc.D. degree in January 1963. A degree in astronautics. "In the hopes that this work will in some way contribute to their exploration of space, this is dedicated to the crew members of this country's current and future manned space programs." I wish I could join them in their exciting ventures! Aldrin's doctoral thesis was in the hopes of assisting him in his selection as an explorer, but it required foregoing test pilot training, which was a prerequisite at the time.

Aldrin, a doctorate, was sent to the Gemini Target Office of the Air Force Space Systems Division in Los Angeles, where he was assisting in increasing the maneuverability of the Agena target vehicle, which was to be used by NASA's Project Gemini. He was then transferred to NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, where he was instrumental in integrating Department of Defense experiments into Project Gemini flights.

NASA career

When NASA's Astronaut Group 2 was chosen in 1962, Aldrin first applied to join the astronaut corps. His application was refused on the grounds that he was not a test pilot. Aldrin was aware of the need and asked for a waiver, but the request was turned down. NASA revealed another round of applicants on May 15, 1963, this time with the condition that applicants had either test pilot experience or 1,000 hours of flying time in jet aircraft. The Aldrin had more than 2,500 hours of flying time, of which 2,200 was in jets. He was chosen one of fourteen members of NASA's Astronaut Group 3 on October 18, 1963. He was the first astronomer with a doctoral degree, which, along with his expertise in orbital mechanics, earned him the nickname "Dr. Rendezvous" from his fellow astronauts. Despite Aldrin's being both the most educated and the rendezvous specialist in the astronaut corps, he was aware that the word was not intended as a compliment. Each new explorer was given a field of expertise upon completion of initial training; in Aldrin's case, mission planning, trajectory analysis, and flight plans were all assigned; in Aldrin's case, it was mission planning, trajectory analysis, and flight planning.

Gemini 10, commander and pilot Jim Lovell were selected as the backup crew. Backup crews were usually the prime crew of the third mission's return, but Gemini 12 was the last scheduled mission in the program. Due to Elliot See and Charles Bassett's deaths in an air crash on February 28, 1966, Lovell and Aldrin were moved up one mission to backup for Gemini 9, putting them in position as the prime crew for Gemini 12. They were designated as their prime crew on June 17, 1966, with Gordon Cooper and Gene Cernan as their back-ups.

Gemini 12's initial mission goals were uncertain. It was primarily scheduled to complete tasks that had not been carried out or entirely carried out on previous missions. Although NASA had successfully launched Rendezvous during Project Gemini, the gravity-gradient stabilization test on Gemini 11 was unsuccessful. Extravehicular activity had also raised questions for NASA (EVA). Cernan's opinion on Gemini 9 and Richard Gordon on Gemini 11 had been drained from being on call during EVA, but Michael Collins had a fruitful EVA on Gemini 10, which showed that the order in which he had performed his duties was a significant factor.

It was therefore incumbent on Aldrin to complete Gemini's EVA targets. To give him a chance of succeeding, NASA formed a task group. The testing of the Air Force's astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU) that had caused Gordon's concern on Gemini 11 was postponed, but Aldrin could rely on EVA. NASA redesigned the education program, opting for submarine education rather than parabolic flight. However, an aircraft operating on a parabolic course had given astronauts an experience of weightlessness in preparation, but there was a delay between each bola that allowed astronauts several minutes of rest. In addition, it accelerated the completion of tasks, but they had to be done slowly and deliberately in space. A better simulation was conducted after a viscous, buoyant fluid fluid model. On Gemini 12, NASA added handholds to the capsule, which were also increased from nine to 44, as well as creating workstations where he could anchor his feet.

Gemini 12's primary objectives were to rendezvous with a target vehicle and fly the spacecraft and target vehicle together using gravity-gradient stabilization, perform docket maneuvers using the Agena propulsion system to change orbit, conduct a tetherless stationkeeping exercise and three EVAs, and demonstrate automatic reentry. Gemini 12 also undertook 14 scientific, medical, and technological experiments. It was not a trailblazing mission; a rendezvous from above had already been carried out by Gemini 9, and Gemini 11's tethering of vehicles was not a success. Even gravity-gradient stabilization had been attempted by Gemini 11, but it was unsuccessful.

On November 11, 1966, Gemini 12 was launched at Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 19 at 20:46 UTC. About an hour and a half before, the Gemini Agena Target Vehicle had been delivered about an hour and a half before. The mission's first major target was to rendezvous with this target vehicle. As the target and Gemini 12 capsule came closer together, radar communications between the two teams degraded until it became unusable, prompting the crew to rendezvous manually. Aldrin helped Lovell get the right details to dock with the target vehicle by using sextant and rendezvous charts. With an Agena target vehicle, Gemini 12 achieved the fourth docking.

The next challenge was to get back to undocking and docking. Lovell was forced to free the spacecraft by undocking, one of the three latches stuck, and he had to use the Gemini's thrusters to free it. A few minutes later, Aldrin docked again successfully. The flight crew requested that the Agena main engine be fired to propel the docked spacecraft into a higher orbit, but the Agena had been missing chamber pressure eight minutes after it had been launched. The Mission and Flight Directors had therefore decided not to risk the main engine. This will be the only mission target that was not fulfilled. Rather, Agena's secondary propulsion system was used to enable the spacecraft to observe the solar eclipse over South America's on November 12, 1966, which Lovell and Aldrin captured through the spacecraft windows.

Aldrin's three EVAs were a hit. On November 12, the first was a stand-up EVA, but not the spacecraft left the building. The standup EVA simulated some of the things he would do during his free-flight EVA so he could estimate the effort expended between the two nations. It set an EVA record of two hours and twenty minutes. Aldrin's free-flight EVA was completed the next day. He scaled to the Agena with the newly installed hand-holds and wired the cables that was needed for the gravity-gradient stabilization experiment. Aldrin carried out a number of tasks, including the installation of electrical wires and testing equipment that would be needed for Project Apollo. He was saved from getting ill after a dozen two-minute rest periods. After two hours and six minutes, his second EVA came to an end. On November 14, Aldrin took photographs and discarded some unnecessary products during a third, 55-minute stand up EVA.

The crew launched the automatic reentry device and crashed down in the Atlantic Ocean on November 15, where they were taken by a helicopter and flown to the awaiting aircraft carrier USS Wasp. His wife discovered he had fallen into depression after the mission, something she had not seen before.

Lovell and Aldrin were sent by an Apollo crew led by Neil Armstrong as Commander, Lovell as Command Module Pilot (CMP), and Aldrin as Lunar Module Pilot (LMP). On November 20, 1967, they were posted as the back up crew of Apollo 9. Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped prime and backup crews, and Armstrong's crew became the backup for Apollo 8, due to manufacturing and assembly delays in the lunar module (LM). Armstrong was expected to command Apollo 11 under the normal crew rotation scheme.

The Apollo 8 prime minister, Michael Collins, needed surgery to remove a bone spur on his spine. Lovell joined the Apollo 8 crew. As Collins recovered, he became CMP for Armstrong's crew. In the meantime, Fred Haise was as a back-up LMP and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8. Though the CMP occupied the center couch on launch, Aldrin occupied it rather than Collins because he had already been taught to operate its console on liftoff before Collins arrived.

Apollo 11 was the second American space mission made up entirely of astronauts who had already flown in space, the first being Apollo 10. The next will not be released until STS-26 in 1988. Armstrong had the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell because some felt it was impossible to work with Aldrin. Deke Slayton, who was in charge of astronaut flight assignments, told Armstrong that Aldrin was fine to work with. Armstrong thought it over for a day before declining. Lovell had no problems being with Aldrin, and he felt he deserved his own authority.

The Lunar Module Pilot was the first to step onto the lunar surface in early versions of the EVA checklist. However, when Aldrin heard that this might be changed, he lobbied within NASA for the original procedure to be followed. Multiple factors contributed to Armstrong's final decision, including the astronauts' physical location within the compact lunar lander, which made it possible for him to be the first to abandon the spacecraft. In addition, Aldrin's views were not shared among senior astronauts who will command later Apollo missions. Collins said that Aldrin "resents not being first on the Moon more than he likes being second." Aldrin and Armstrong did not have time to complete extensive geological education. The first lunar landing primarily concerned about landing on the Moon and safely returning it safely to Earth than the mission's scientific aspects. NASA and USGS geologists briefed the pair. They were on one of the west Texas geological field trip. The journalists followed them, and a helicopter made it impossible for Aldrin and Armstrong to hear their instructor.

An estimated one million spectators watched Apollo 11 from the highways and beaches in the area of Cape Canaveral, Florida, on the morning of July 16, 1969. The launch was shown live in 33 countries, with an estimated 25 million viewers in the United States alone. Millions of people listened to radio shows, with millions more listening to radio broadcasts. Apollo 11 was launched from Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT), and entered Earth orbit just 12 minutes later. The S-IVB's third-stage engine pulled the spacecraft into its orbit toward the Moon after one and a half orbits. The transposition, docking, and extraction operation was carried out about thirty minutes after: it involved separating the command module Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking with lunar module Eagle. After the lunar module was removed, the combined spacecraft launched for the Moon, but the rocket stage flew on a course over the Moon.

Apollo 11 made landfall on July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, standing behind the Moon and launching its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit. The crew caught passing views of their landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquillity, about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of the crater Sabine D's crater at 12:52:00 UTC on July 20, and began final preparations for lunar descent. The Eagles were released from Columbia at 17:44 p.m. on March 17:44:00. Collins, alone aboard Columbia, inspected Eagle to ensure the craft was not destroyed and that the landing gear had correctly deployed.

Aldrin, who was busy piloting the Eagle, called out navigation information throughout the descent. The LM guidance computer (LGC) sent the crew the first of many unexpected alerts indicating that it would not complete all of its tasks in real time and would have to postpone some of them. Its descent burns are about five minutes (1,800 meters) above the moon's surface. Despite this, the Eagle landed at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday, July 20 with about 25 seconds of fuel left.

Aldrin, the first and only person to hold a religious service on the Moon, was a Presbyterian elder. "I'd like to ask every person listening in, whoever and whichever they are located, to pause for a moment and reflect the latest hours of the past few hours" on earth. He took communion and read Jesus' words from the New Testament's John 15:5, as Aldrin says: "I am the vine." You are the branches. For those who remain in me and I, they will produce a lot of fruit; for you, there will be nothing without me." However, he kept this event private due to a lawsuit over the reading of Genesis on Apollo 8. "It was exciting to learn that the very first liquid ever poured on the Moon, as well as the first food eaten there, were communion elements," the poet wrote in 1970.

Aldrin said, "Perhaps, if I had it to do over again, I would not choose to celebrate communion." Whether it was a deeply moving experience for me, it was also a Christian sacrament, and we had come to the moon in the name of all mankind, whether Christians, Jews, Muslims, animists, agnostics, or atheists. However, there could not be a better way to express the enormity of the Apollo 11 experience than by giving thanks to God." "When I considered the heavens, Thy fingers, the moon, and the stars, who Thou hast ordained," Aldrin says. As Aldrin says of faith, photographs of these liturgical documents reveal the conflict's progress.

At 23:43, preparations for the EVA began. Eagle was distraught, and the hatch was opened at 02:39:33 on July 21. Armstrong and Aldrin were keen to go outside, and Eagle was unleashed. On July 21, 1969 (UTC), nineteen minutes after Armstrong first touched the ground, Aldrin set foot on the Moon at 03:15:16. Armstrong and Aldrin were the first and second people to walk on the Moon, respectively. Aldrin's first words after he set foot on the Moon were "Beautiful view," to which Armstrong said, "Isn't that something?" "This is a magnificent sight out here." "Magnificent desolation," Aldrin replied. The Lunar Flag Assembly was impossible to erect, but Aldrin and Armstrong had a problem, but a little persistence brought it to the surface. Although Armstrong captured the scene, Aldrin saluted the flag. Aldrin positioned himself in front of the video camera and began to experiment with new locomotion technologies to help future moonwalkers. President Nixon congratulated the pair on their triumphant landing during these experiments. "Thank you so much, and we look forward to seeing you on the Hornet on Thursday," Nixon said. "I look forward to that a lot, sir," Aldrin said.

Aldrin began photographing and certifying the spacecraft's condition before flight. Aldrin and Armstrong then built a seismometer to record moonquakes as well as a laser beam reflector. While Armstrong inspected a crater, Aldrin began the daunting task of hammering a metal tube into the surface to obtain a core sample. The bulk of the Apollo 11 astronauts' memorable photographs of an explorer on the Moon were of Aldrin; Armstrong appears in just two color photographs; Armstrong appears in just two color photographs. "As the sequence of lunar operations changed," Aldrin said, "Neil had the camera most of the time, and the majority of the photos on the Moon depicting an explorer are of me." We didn't know there were no photographs of Neil until we were back on Earth and in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory looking through the photographs. Well, it's probably my fault, but we hadn't seen this during our preparations."

Aldrin reentered Eagle first, but he later reported that he became the first person to urinate on the Moon, according to Aldrin. They attached film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the hatch with some difficulties, using a flat cable pulley system. Armstrong alerted Aldrin of a bag of memorial items in his sleeve pocket, and Aldrin toss it down. It contained a mission patch for the Apollo 1 flight that Ed White never flew due to a cabin fire during the launch rehearsal; medallions naming Yuri Gagarin, the first man to die in a space flight; and Vladimir Komarov, the first man to die in a space flight; and goodwill messages from 73 nations. The explorers lightened the ascent stage of lunar orbit by taking out their backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment after transferring to LM life support. At 05:01, the hatch was closed again, but they repressurized the lunar module and settled to sleep.

They took off in Eagle's ascent stage to rejoin Collins aboard Columbia in lunar orbit at 17:54 UTC. The ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit after rendezvous with Columbia, and Columbia returned to Earth. On July 24, it crashed in the Pacific 2,660 kilometre (1,440 nmi) east of Wake Island at 16:50 UTC (05:50 local time) at 16:50 UTC (05:50 local time). The total mission duration was 195 hours, 18 minutes, 35 seconds.

Pathogens returning from the lunar surface was considered a possibility, even remote, as divers sold biological isolation jackets (BIGs) to the astronauts and carried them into the life raft. The astronauts were winched on board the rescue helicopter and flown to USS Hornet, where they spent the first part of the Earth-based portion of 21 days quarantine. The three astronauts rode in ticker-tape parades in their honour in New York and Chicago on August 13, drawing an estimated six million people. The flight was commemorated at an official state dinner in Los Angeles that evening. President Richard Nixon honoured each of them with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States, (with distinction).

The astronauts thanked the representatives for their continued assistance on September 16, 1969, and encouraged them to keep funding the space program. On September 29, the astronauts began a 38-day world tour that took them to 22 foreign countries and included visits with leaders from multiple countries. The crew returned to the United States on November 5, 1969, after completing the tour in Australia, South Korea, and Japan.

Aldrin was still delivering addresses and making public appearances after Apollo 11. He joined Soviet cosmonauts Andriyan Nikolayev and Vitaly Sevastyanov on their tour of the NASA space centers in October 1970. He was also involved in the creation of the Space Shuttle. Aldrin, a colonel, saw few prospects at NASA and returned to the Air Force on July 1, 1971, putting the Apollo program to an end. He had spent 289 hours and 53 minutes in space, of which 7 hours and 52 minutes were in EVA.