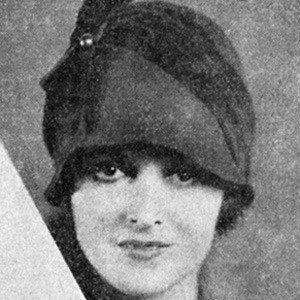

Mary Astor

Mary Astor was born in Quincy, Illinois, United States on May 3rd, 1906 and is the Movie Actress. At the age of 81, Mary Astor biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 81 years old, Mary Astor physical status not available right now. We will update Mary Astor's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Mary Astor (born Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke) was an American actress who appeared on May 3, 1906 – September 25, 1987) was a British actress.

Brigid O'Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon (1941), she may be best known for her appearance in The Maltese Falcon (1941).

Sandra Kovak, a concert pianist, received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in The Great Lie (1941).

Astor began her long-shot movie career as a teenager in the early 1920s' silent films.

Her voice was initially considered too feminine, and she was off the screen for a year when talkies first emerged, but she was not comfortable.

Since her appearance in a film with friend Florence Eldridge, the actress was able to resume her interest in talking pictures.

Her career was practically ended by scandal in 1936.

Astor was involved with playwright George S. Kaufman and was branded an adulterous wife by her ex-husband in a custody fight over her daughter.

Astor had more success on film, winning the Academy Award for Best Support Actress for her role in The Great Lie (1941).

Astor was a part of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract during the 1940s and later worked in film, television, and on stage until she retired in 1964.

She wrote five books.

Her autobiography, as well as her later book, A Life on Film, which was about her career, was a best-seller. "When two or three people love the cinema gather together, the name of Mary Astor always comes up, and most agree that she was an actress of special attraction," director Lindsay Anderson wrote about Astor in 1990.

Early life and career

Astor was born in Quincy, Illinois, the only child of Otto Ludwig Langhanke (October 2, 1871 – February 3, 1943) and Helen Marie de Vasconcellos (January 19, 1881 – January 18, 1947). Both of her parents were educators. Her German father immigrated to the United States from Berlin in 1891 and became a naturalized citizen; her American mother was born in Jacksonville, Illinois, and had Portuguese roots; her German mother was born in Jacksonville, Illinois; and her German mother was born in Berlin, Illinois. They married in Lyons, Kansas, on August 3, 1904.

Before World War I, Astor's father taught German at Quincy High School until the United States entered World War I. He later took up farming. Astor's mother, who had always wanted to be an actress, taught drama and elocution. Astor was home-schooled in academics and was taught to play the piano by her father, who insisted that she practice daily. In her film The Great Lie and Meet Me in St. Louis, her piano skills came in handy.

In 1919, Astor submitted a photograph of herself to a beauty competition in Motion Picture Magazine, becoming a semifinalist. When Astor was 15, the family moved to Chicago, Illinois, with her father teaching German in public schools. Astor took drama lessons and appeared in a number of amateur stage productions. She submitted another photograph to Motion Picture Magazine the following year, this time as a finalist and then runner-up in the national competition. Her father moved the family to New York City in order for his daughter to be able to be in motion pictures. She operated from September 1920 to June 1930.

Charles Albin, a Manhattan photographer, saw her photograph and begged the teenage girl with haunting eyes and long auburn hair whose nickname was "Rusty" to pose for him. Harry Durant of Famous Players-Lasky and Astor was seen in Albin's photographs and Astor was signed to a six-month contract with Paramount Pictures. During a conference with Paramount Pictures chief Jesse Lasky, film director Walter Wanger, and gossip columnist Louella Parsons, she was changed to Mary Astor.

Lillian Gish, who was so impressed with her recitation of Shakespeare that she fired a thousand feet of her, directing Astor's first film performance. She made her debut in the 1921 film Sentimental Tommy, but her tiny role in a dream sequence ended up on the cutting room floor. Paramount allowed her employment to lapse. She then appeared in some film shorts with sequences based on famous paintings. She was given a prestigious award for her 1921 two-reeler The Beggar Maid. John Smith (1922), her first feature-length film, was followed by The Man Who Played God the same year. She and her parents immigrated to Hollywood in 1923.

She was signed by She had appeared in several larger films, this time to a one-year deal worth $500 a week. Since appearing in many more films, John Barrymore saw her image in a magazine and wanted her role in his forthcoming film. She starred with him in Beau Brummel (1924) on loan out to Warner Bros. The older actress wooed the young actress, but Astor's parents' refusal to encourage the pair to spend time alone; Mary was only seventeen and legally blind. It was only after Barrymore told the Langhankes that his acting lessons necessitated anonymity that the pair managed to be alone at all. They were largely disappointed because of Langhankes' interference and Astor's inability to evade their heavy-handed authority, as well as because Barrymore became acquainted with Astor's fellow WAMPAS Baby Star Dolores Costello, who later married. Astor's parents purchased a Moorish style mansion with 1 acre (4,000 m2) of land above Hollywood in 1925. The Langhankes not only lived off Astor's income, but they also kept her a virtual prisoner inside Moorcrest. Moorcrest is known not only for its ornate style, but also for its location as the most luxurious residence associated with the Kroton Colony, a utopian society established by the Theosophical Society in 1912. The house was designed by Marie Russak Hotchener, a Theosophist who had no formal architectural education, and includes Arts and Crafts features such as art-glass windows (whose red lotus design Astor called "unfortunate") and Batchelder tiles. The Moorcrest, which has since undergone a multi-million-dollar makeover, is still standing. It was rented by Charlie Chaplin, whose tenure is commemorated by an art glass window with the Little Tramp logo before the Langhankes bought it.

Astor's parents were not Theosophists, but the family was friendly with both Marie Hotchener and her husband Harry, both influential Theosophical Society members. Marie Hotchener negotiated Astor's right to a $5 a week allowance (at a time when she was making $2,500 a week) and the right to go to work unchaperoned by her mother. As she was 19 years old, Astor, fed up with her father's constant physical and emotional abuse, as well as his financial independence, climbed from her second floor bedroom window to a Hollywood hotel, as outlined in her memoirs. Hotchener aided in her recovery by convincing Otto Langhanke to make Astor's account with $500 and the ability to come and go as she pleased. However, she didn't gain control of her salary until she was 26 years old, when her parents sued her for financial assistance. Astor negotiated a divorce by promising to pay her parents $100 a month. Otto Langhanke put Moorcrest up for auction in the early 1930s, hoping to sell more than the $80,000 he had been selling for it; it went for $25,000.

Astor has appeared in films at various studios. She was a member of Warner Bros when her Paramount deal came to an end in 1925. Another role with John Barrymore, this time in Don Juan (1926), was one of her assignments. Fay Wray, Reginal, Dolores Costello, Joan Crawford, Dolores del Ro, Janet Gaynor, and Fay Wray were among the WAMPAS Baby Stars in 1926. Astor appeared in Dressed to Kill (1928), which received positive feedback, and the sophisticated comedy Dry Martini (also 1928). "She later said that while working on the former, she "absorbed and assumed some of the scene's emotional and emotional climate." It was "a new and exciting point of view," she said; with its explicit doctrine of self-indulgence, it plunged into the void of my moral conviction and captivated me completely." She had signed a Fox deal for $3,750 a week when her Warner Bros. deal came to an end. She married director Kenneth Hawks at her family's house in 1928, Moorcrest. The bride gave her a Packard automobile as a wedding gift, and the couple moved into a house on Lookout Mountain in Los Angeles, west of Beverly Hills. Fox conducted a sound test, but she failed because the studio discovered her voice to be too deep as the film industry transitioned to talkies. Despite the fact that the studio released her from her position and inexperienced technicians, she found herself out of work for eight months in 1929.

Astor took voice training and singing lessons with Francis Stuart, an exponent of Francesco Lamperti, but no roles were given during her absence. Florence Eldridge, the widow of Fredric March), who confided, gave her acting career a boost. Eldridge, who was going to star in Among the Married at the Majestic Theatre in Downtown Los Angeles, recommended Astor for the second female lead. The performance was a hit, and her voice was deemed appropriate, despite being described as poor and vibrant. She was excited to return to work, but her joy was quickly fading. Kenneth Hawks was killed in a mid-air plane crash over the Pacific on January 2, 1930, while filming scenes for the Fox film Such Men Are Dangerous. When Florence Eldridge announced it, Astor had just ended a matinee performance at the Majestic. She was rushed from the theater to Eldridge's apartment. Doris Lloyd, a replacement, appeared on the next show. Astor lived at Eldridge's apartment for a brief period of time, then returned to work soon after. She debuted in her first talkie, Ladies Love Brutes (1930) at Paramount, where she costarred with her friend Fredric March shortly after her husband's death. Though her career progressed, her personal life was still difficult. She suffered delayed grief over her husband's death and had a nervous breakdown after working on several other films. Dr. Franklyn Thorpe, whom she married on June 29, 1931, attended her in the months of her illness. She appeared in Smart Woman in 1985, portraying a woman determined to save her husband from a gold-digging relationship.

The Thorpes purchased a yacht and sailed to Hawaii in May 1932. In August, Astor was planning a baby but gave birth in Honolulu in June. The child, who was born in a family's name, was named Marylyn Hauoli Thorpe; her first name combined her parents' names, and her middle name is Hawaiian. As they returned to Southern California, Astor freelanced and took on Barbara Willis' pivotal role in MGM's Red Dust (1932) with Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. Astor signed a star contract with Warner Bros in late 1932. In the meantime, her parents invested heavily in the stock market, which often turned out to be unprofitable. Astor branded it a "white elephant" while they were in Moorcrest, and she refused to maintain the house. To pay her bills, she had to go to the Motion Picture Relief Fund in 1933. In the Kennel Murder Case (1933), she appeared as the female lead and niece of the murder victims, alongside William Powell as detective Philo Vance. In the August 1984 issue of Films in Review, film critic William K. Everson called it a "masterpiece."

Astor wanted a divorce by 1933, becoming dissatisfied with her marriage due to Thorpe's short temper and a habit of naming her faults. She took a break from film-making in 1933 and stayed in New York alone, at a friend's suggestion. She was in a good but casual relationship while enjoying a whirlwind social life. In her diary, she chronicled their affair. Thorpe had found Astor's diary by now using his wife's funds. He said that her ties with other men, including Kaufman, would be used to argue that she was an unfit mother in any divorce hearing.

In April 1935, Dr. Franklyn Thorpe divorced Astor. In 1936, a custody controversy over their four-year-old daughter, Marylyn, drew widespread notice. During the trial, Astor's diary was never officially admitted as evidence, but Thorpe and his attorneys regularly referenced it, and its notoriety soared. Following the thief of the diary from her desk, Astor confessed to the fact that the diary existed and that she had chronicled her affair with Kaufman. Thorpe had taken down pages referring to him and had created fake material, making the diary inadmissible as a mutilated document. Goodwin J. Knight, the trial judge, ordered that the trial judge seal and impounded it. Florabel Muir, who then worked with the New York Daily News, is accused of inventing fabricated diary passages in her journals. Interestingly, the plot in a 1934 Perry Mason film in which Astor had recently co-starred, The Case of the Howling Dog, involved an attempt to access a woman suspect's incriminating diary in a murder lawsuit involving her married boss.

When Astor's role in Dodsworth (1936), as Edith Cortwright, was revealed, news of the diary became widely circulated. Samuel Goldwyn was advised to leave her after her deal contained a morality clause, but Goldwyn refused. Dodsworth's debut on Broadway garnered raves, and the public's acceptance told the studios that casting Astor was still a viable option. In the end, the scandals did no harm to Astor's career, which was actually revived due to the custody war and the media coverage it generated.

Astor's diary was retrieved from the bank vault in 1952 by a court order, where it had been sequestered for 16 years and destroyed.

She returned to the stage in 1937 in Nol Coward's Tonight, The Astonished Heart, and Still Life. She also began appearing on radio regularly. She appeared in The Prisoner of Zenda (1937), John Ford's The Hurricane (1937), Midnight (1939) and Brigham Young (1940). Astor played scheming temptress Brigid O'Shaughnessy in John Huston's all-time classic The Maltese Falcon (1941). Dashiell Hammett's book was also based on Humphrey Bogart's novel and starred Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet. In the 14th Academy Awards, she received an award for her appearance in The Great Lie (also 1941). Sandra Kovak, the self-absorbed concert pianist who relinquishes her unborn child, was played by George Brent, but Bette Davis was the film's star. After seeing her screen test and hearing her play Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 5, Davis wanted Astor cast in the role. 1. Davis then recruited Astor to assist in rewriting the script, which Davis found to be mediocre and needed to make it more interesting. Astor continued Davis' directions by sporting a bobbed hairdo for the role.

pianist Max Rabinovitch dubbed the film's soundtrack, which includes ferocious hand movements on the piano keyboard. Davis took a step back to allow Astor to shine in her leading roles. Bette Davis and Tchaikovsky were lauded in her Oscar acceptance address. Astor and Davis became close friends.

Despite these successes, Astor was not promoted to the top of the Hollywood elite. She has always turned down offers to act in her own right. She preferred the ease of being a regular celebrity over top billing and not wanting to carry the photo. In John Huston's Across the Pacific (1942), she reunited with Humphrey Bogart and Sydney Greenstreet. Astor, who was usually cast in dramatic or melodramatic roles, showed a flair for comedy in his Preston Sturges film, The Palm Beach Story (also 1942) for Otto Langhanke, Astor's father, died in Cedars of Lebanon Hospital as a result of a heart attack exacerbated by influenza in February 1943. His wife and daughter were at his bedside.

Astor signed a seven-year deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), a move she soon regretted. She was kept busy, playing what seemed to be underwritten and largely interchangeable supporting roles, a category Astor later described as "Mothers for Metro." The studio allowed Me in St. Louis (1944) to make her Broadway debut in Many Happy Returns (1945). The play was a failure, but Astor received positive feedback. She appeared on loan out in 20th Century Fox, Claudia and David (1946). She was also loaned to Fritzi Haller, the tough owner of a small mining town, was also loaned to Astor and her mother, who was delirious and didn't know her, sat in the hospital room with her mother before Helen Langhanke died of a heart disease in January 1947, and listened intently as Helen explained to her all about horrific, selfish Lucile. Astor said she spent hours copying her mother's diary so she could read it and was surprised to discover how much she loached it after her death. Astor, who was then in undistinguished, colorless mother roles, returned to MGM. One notable exception was when she appeared as a prostitute in the film noir Act of Violence (1948). In Little Women (1949), she was cast as Marmee March. Astor refused to recover in playing what she considered another humdrum mother, and she became dispondent. In her memoir A Life on Film, she later referred to her dissatisfaction with her cast members and the shooting.

The studio wanted to extend her contract, securing better roles, but she turned down the bid.

Astor's drinking was also becoming increasingly problematic. She admitted to alcoholism as early as the 1930s, but it had never interfered with her work or results. She came to a crashing point in 1949 and later became a alcoholic sanitarium.

She made a frantic call to her doctor in 1951, claiming she had taken too many sleeping pills. She was admitted to a hospital and police announced that she had attempted suicide, marking her third overdose in two years. The story broke national television news. It had been an accident, she said.

She joined Alcoholics Anonymous and converted to Roman Catholicism that same year. Peter Ciklic, a licensed psychologist who also encouraged her to write about her therapy, attributed her recovery to a priest. Thomas Wheelock, a stockbroker who married on Christmas Day 1945, divorced her fourth husband, but not before 1955.

She appeared in the leading role of The Time of the Cuckoo in 1952, when it was later turned into the film Summertime (1955) and later toured with it. Astor lived in New York for four years and worked in theater and television. Astor, a lifelong Democrat, supported Adlai Stevenson's campaign in 1952.

She made her television debut in The Missing Years (1954) for Kraft Television Theatre. During the following years, she appeared on several major television shows of the day, including The United States Steel Hour, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Rawhide, Burke's Law, and Ben Casey. She appeared in the Gary Merrill NBC series Justice's episode "Fearful Hour" in 1954 in the role of a struggling young and elderly film actress who wishes to avoid being identified as a robber. In an episode titled "Rose's Last Summer," she appeared as an ex-film actor on the Boris Karloff-hosted Thriller.

She appeared on Broadway again in The Starcross Story (1954), another failure, and in 1956, she returned to southern California. She then embarked on a fruitful theatre tour of Don Juan, directed by Agnes Moorehead and co-starring Rigo Montalbán.

My Story: An Autobiography of Astor was published in 1959, becoming a success in its day and a bestseller. It was Father Ciklic's request that she write. Although she spoke of her personal life, her parents, her marriages, the fight against alcoholism, and other aspects of her life, she did not discuss the film industry or her career in depth. A Life on Film, her second book, was published in 1971, where she explored her work. It became a best-selling book, as well as the one above. Astor tried her hand at literature, writing The Image of Kate (1960), which was published in a German translation as years and months (1964), Goodbye, Darling, be Happy (1965), and A Place Called Saturday (1968).

During this period, she appeared in many films, including Stranger in My Arms (1959). Roberta Carter, Allison Mackenzie's domineering mother who claims that the "shocking" book she wrote should be banned from the school library, received positive feedback for her performance. In her last scene of the film, where Roberta's vindictive motives are revealed, Astor invented memorable bits of industry, according to film historian Gavin Lambert.

Astor was lured away from her Malibu, California home, where she was gardening and writing on her third book, to make what she thought would be her last film after a trip around the world in 1964. Jewel Mayhew, a small figure in the murder mystery Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), starring her friend Bette Davis, was given the small role. Cecil Kellaway appeared in her last scene at Oak Alley Plantation in southern Louisiana. "A Life on Film" actress Deborah Johnson portrayed her role as "a little old lady, waiting to die." Astor has decided that it would be her swan song in the film business. She retired after 109 movies in a 45-year career, earning her Screen Actors Guild card and resigned.

Anthony del Campo, Astor's third marriage, to Mexican film editor Manuel del Campo) and his family until 1971, she and her husband, Anthony del Campo, later moved to Fountain Valley, California, where she and her son, Anthony del Campo, lived near her son, Anthony del Campo. She moved to a small cottage on the grounds of the Motion Picture & Television Country House, the company's retirement facility in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, where she had a private table when she desired to eat in the resident dining room that year, suffering from a chronic heart disease. She appeared in the television documentary film Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film (1980), co-produced by Kevin Brownlow, in which she reflected on her appearances during the silent film period. She had been invited to appear in Brownlow's documentary by a former sister-in-law Bessie Love, who also appeared in the series, after years of retirement.

While in the hospital at the Motion Picture House complex, Astor died on September 25, 1987, at the age 81, of respiratory disease due to pulmonary emphysema. She is laid to rest in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. On the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6701 Hollywood Boulevard, Astor has a motion pictures actor.