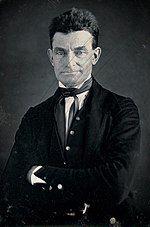

John Brown

John Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut, United States on May 9th, 1800 and is the War Hero. At the age of 59, John Brown biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 59 years old, John Brown physical status not available right now. We will update John Brown's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist.

To overthrowrown the United States' institution of slavery, Brown advocated for the use of armed rebellion.

He first attracted national attention when he led small groups of volunteers during the 1856 Bleeding Kansas disaster.

"These guys are all talk," he was dissatisfied with the pacifist movement's pacifism: "These guys are all talk."

What we need is action—action!"

In May 1856, Brown and his allies killed five supporters of slavery in the Pottawatomie massacre, which responded to Lawrence's sacking by pro-slavery forces.At the Battle of Black Jack (June 2) and the Battle of Osawatomie (August 30, 1856), Brown then led anti-slavery troops. Brown led a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, today West Virginia), in the hopes of spreading slave disemination throughout Virginia and North Carolina; there was a draft constitution for the state he wanted to establish in October 1859.

He seized the armoury, but seven people were killed and ten or more were wounded, but ten or more were wounded.

He had intended to arm slaves with weapons from the arsenal, but only a small number of local slaves revolted.

Many of Brown's men who had not fled were killed or injured by local farmers, militiamen, and US Marines, the former led by Robert E. Lee.

He was convicted on all counts and jailed on treason charges against the Commonwealth of Virginia, the murder of five men (including three blacks) and sparked a slave revolt;

He was the first person convicted of treason in the United States, according to historians, the Harpers Ferry raid and Brown's trial, both widely covered by the national media, escalated tensions that resulted in the South's secession and the American Civil War.

Brown's raid captured the nation's attention; southerners feared that it would be the first of many Northern plans to spark a slave revolt that might endanger their lives; Republicans denied the assertion and said that they would not interfere with slavery in the South.

The popular Union marching song "John Brown's Body" depicted him as a martyr. Brown's behaviour as an abolitionist and the tactics he used make him a controversial figure today.

He is both remembered as a hero and visionary, and as a murderer and a terrorist.

Historian James Loewen reviewed American history textbooks and concluded that historians regarded Brown perfectly from 1890 to 1970, but that new interpretations began to take center stage.

Early life and family

In Torrington, Connecticut, John Brown was born on May 9, 1800. Owen Brown (1771–1856) and Ruth Mills (1772–1808), his fourth child, described his parents as "poor but respectable." Capt. Owen Brown's father was Capt. John Brown (1728–1776), a New York immigrant who died on September 3, 1776, is a scholar who fought in the Revolutionary War; John Brown moved his grandfather's tombstone to his farm in North Elba, New York. Brown descended from Peter Browne, one of the Pilgrim Fathers, who landed from the Mayflower in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1857. There are some historians who believe Peter Brown, his ancestor, arrived in Connecticut in 1650.

His mother, who was both a Dutch and Welsh descendant, was 5 years old at Gideon Mills, and also an army officer in the Revolutionary Army. Anna Ruth, her older sister, was born in 1798, and his younger brothers Salmon and Oliver Owen were born in 1802 and 1804, respectively. Oliver Owen was also an abolitionist. Frederick, a brother who was in jail while he was in jail, was also on death row, awaiting execution.

Although Brown was a child, his father moved the family to West Simsbury, Connecticut, for a short time. The family migrated to Hudson, Ohio, which at the time was mainly wilderness; on the 5th, it became the country's most anti-slavery zone. David Hudson, Hudson, with whom John's father had frequent contact, was an abolitionist and an advocate for "forcible resistance by the slaves." Owen Brown, a 17-year-old boy from Hudson, has been a leading and wealthy citizen. Jesse Grant, the father of President Ulysses S. Grant, operated a tannery and employed him. For several years, Jesse was in debt with the Brown family. Owen feared slavery and was involved in Hudson's anti-slavery movement and discussion, providing Underground railroad prisoners a safe home. John attended Elizur Wright, the father of the famous Elizur Wright, in Hudson, at a time when there was no school beyond the elementary school. Ruth, a 17-year-old boy from St. John, died in 1808. He wrote an ode to her in his memoir that he cried for years. Although he loved his father's new wife, he never felt a strong emotional connection with her.: 8 : 427

In a tale he told his family, when he was 12 years old and away from home moving cattle, he worked for a man with a colored baby who had been beaten against him with an iron shovel. Brown asked him why he was treated so well, the answer was that he was a slave. It was the time when John Brown decided to dedicate his life to improving African Americans' wellbeing, according to Brown's uncle-in-law Henry Thompson.

Brown, a 16-year-old boy, left his family for New England to pursue a liberal education and become a Gospel minister. He consulted and conferred with the Rev. He consulted and advised the people. Jeremiah Hallock, a clergyman in Canton, Connecticut, whose wife was a cousin of Brown's, was a member of Brown's, and he was escorted to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where he was under the late Rev.'s instruction. Moses Hallock, he was preparing for college. He may have stayed at Amherst College, 13: 17, but he suffered from eye inflammation that eventually became chronic, and barred him from further study, and he returned to Hudson.

Brown, 31, spent a short time at his father's tannery before establishing a flourishing tannery outside of town with his adopted brother Levi Blakeslee. Brown, a good cook, maintained the bachelor's quarters, and the two were a success. 17 He had his bread baked by a widow, Mrs. Amos Lusk. Brown advised her not to handle his housekeeping as the tanning industry had expanded to include journeymen and apprentices. Dianthe and her daughter Dianthe were able to live in his log cabin. Brown married Dianthe in 1820, but there is no known photograph of her, but he described Dianthe as "a remarkably bare, but lovely, industrious, and inexpensive girl, of exceptional character, earnest piety, and common sense." "32 Their first child, John Jr., was born 13 months earlier." Dianthe had seven children and died as a result of childbirth problems in 1832. 18–19

Brown was well versed in Bible study, and he could spot even small mistakes in Bible recitation. He never used cigarettes, coffee, or alcohol. Plutarch's Lives and Cromwell's Favorite Books after the Bible were among his favorite books, as well as Napoleon and Cromwell's biography.

After leaving Hudson, John Brown lived in Pennsylvania for longer than he did somewhere else. According to a Pennsylvania friend who visited him in jail in Charles Town right before his execution, Crawford County, Pennsylvania, was extremely important to him because two of his children and his wife were buried there.

Brown and his family, determined a safer place for fugitive slaves in 1825, despite the tannery's success and building a large house the year before, migrated to New Richmond, Pennsylvania. He bought 200 acres (81 hectares), cleared an eighth of it, and built a cabin, a two-story tannery with 18 vats, and a barn; in the former, a mysterious, well ventilated room to hide escaping slaves. 4–5 Brown's tannery was a crucial stop on the Underground Railroad from 1825 to 1835, and during this period, Brown is said to have helped 2,500 enslaved people on their journey to Canada.

Brown made money surveying new roads. He was instrumental in the establishment of a school, which first met in his house, and finding a preacher. 23 years old He helped establish a post office in Randolph, Pennsylvania, and in 1828, President John Quincy Adams appointed him the first postmaster of Randolph, Pennsylvania; he continued to run the mail until he left Pennsylvania in 1835. He was fined $800 in Meadville for refusing to serve in the military. Brown, as well as Seth Thompson, a kinsman from eastern Ohio, operated an interstate cattle and leather company during this time.: 7

Any white families in 1829 begged Brown to help them discourage Native Americans from hunting every year in the area. Brown denied calling it a cruel act. 168–69 As a child in Hudson, John got to know local Native Americans and learned a few words of their spoken. 7 He led them on hunting trips and invited them to eat in his house.

Brown was instrumental in the establishment of a Congregational Society in Richmond, whose first meetings were held in the tannery.: 6

Frederick (I) Brown's son Frederick (I) died in 1831 at the age of four. Brown was sick, and his companies began to fail, leaving him in a lot of debt. His mother Dianthe died in the summer of 1832, just after the death of a newborn son, whether as a result of birth or an immediate result of it. (II): 35 He was left with the children John Jr., Jason, Owen, Ruth, and Frederick. Brown married 17-year-old Mary Ann Day (1817–1884), a native of Washington County, New York; she was Brown's youngest sister at the time. 8 They would eventually have 13 children, seven of whom were sons of slave laborers in the fight to abolish slavery.

Brown and his family immigrated from Pennsylvania to Franklin Mills, Ohio, in 1836. In partnership with Zenas Kent, he borrowed heavily to buy property in the area, including property along canals, and developed and operated a tannery along the Cuyahoga River. Zenas was the father of Marvin Kent, and in Marvin's honor, the Mills family is now known as Kent, Ohio. Brown became a bank director and was expected to earn $20,000 (equivalent to $525,355 in 2021). 50 Like many businessmen in Ohio, he invested too much in credit and state bonds and suffered heavy financial losses during the Panic of 1837. Brown was sentenced to prison for attempting to hold a farm by occupying it against the claims of the new owner in one episode of property theft.

According to daughter Ruth Brown's husband Henry Thompson, whose brother was killed at Harpers Ferry, he was killed in Franklin Mills.

He seemed to flounder hopelessly from one thing to another without having a plan for three or four years. He went through several company attempts in an attempt to get out of debt, as with other steadfast men of his day and history. He bred horses for a short time but had to pull it off when he learned that customers were using them as race horses. He did some surveying, farmed, and did some tanning. 50-51 In 1837, Brown vowed to be "Here, in the presence of these witnesses, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery." Brown declared bankruptcy in federal court on September 28, 1842. Charles, Peter, Austin, three of his children died of dysentery in 1843.

Brown had a reputation as a top sheep and wool specialist from the mid-1840s. He was Captain Oviatt's farm for about a year, and he and Col. Simon Perkins of Akron, Ohio, became a joint venture with Col. Simon Perkins, whose flocks and farms were managed by Brown and his sons. Brown and his family lived across the street from the Perkins Stone Mansion on Perkins Hill.

At the Ohio State Fair in 1852, he received five first prizes for his sheep and cattle.

Brown migrated to Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1846, as an agent for Ohio wool growers in their business with New England woolen products' suppliers, but also as a means of advancing his scheme of emancipation. The white leaders, as well as "The publisher of The Republican, one of the country's most influential newspapers," were heavily invested and emotionally invested in the anti-slavery movement.

The city's African-American abolitionists had established the Sanford Street Free Church, now known as St. John's Congregational Church, two years before Brown's arrival in Springfield, 1844, which became one of the country's most prominent abolitionist sites. Brown was a member of the Free Church of Springfield, England, where he attended abolitionist lectures delivered by Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth in 1846. Douglass spent a night with Brown in 1847, the Free Church's founder, after which Douglass wrote, "From this night spent with John Brown in Springfield, Mass." [In] 1847, although I continued to write and speak out against slavery, I became more and more concerned with its nonviolent abolition. The color of this man's prominent images tinged my utterances." During Brown's time in Springfield, he became deeply involved in the city's transformation into a major center of abolitionism and one of the country's safest and most important stops on the Underground Railroad. Brown was a member of the 1848 Revolution by his colleague Henry Highland Garnet of David Walker's Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829).

The Fugitive Slave Act, which mandated that authorities in free states assist slave owners in the return of free slaves and putting sanctions on those who assist in their escape, was passed before Brown left Springfield in 1850. The League of Gileadites, Brown's reaction, formed a resistance group to prevent the recapture of fugitives. Mount Gilead was the place where only the bravest Israelites gathered to face an enslaved enemy in the Bible. "Nothing so charms the American people as much as personal courage," Brown said of the League. [Blacks] will have ten times more [of white neighbors] than [they] had, but they would have to have their privileges first and foremost than to imitate their white neighbors' follies and excesses, as well as indulge in idle show, in ease, and luxury." He ordered the League to act "quickly, quietly, and effectively" to shield slaves that had escaped to Springfield, a term that would predate Brown's later activities preceding Harpers Ferry. Not one individual was ever arrested from Springfield, beginning with Brown's establishment of the League of Gileadites. As a gesture of compassion, Brown gave his rocking chair to Thomas Thomas Thomas, his beloved black porter, as a sign of love.

Brown, who later received financial assistance from New England's most prominent merchants, allowed him to hear and speak with nationally respected abolitionists, such as Douglass and Sojourner Truth, as well as the League of Gileadites. Brown also helped publicize David Walker's speech Appeal during this period. Brown's personal views changed in Springfield, as he witnessed the success of the city's Underground Railroad and began his first steps toward radical, anti-slavery organizations. In addresses, he referred to the martyrs, Elijah Lovejoy and Charles Turner Torrey, as whites "will assist blacks in escaping slave-catchers." Brown discovered in Springfield, California, a man whose anti-slavery passions were shared, and each one seemed to educate the other. Brown's Springfield years, both successes and failures, were a transformative period of his life that inspired a lot of his later activities.

Amelia died in 1846 and Emma in 1849.

Brown, a bankrupt and having lost the family's home, learned of Gerrit Smith's Adirondack land grants to poor Black men in 1848, who Brown later identified Timbuctoo, and decided to relocate his family to a farm in the area where he could give them advice and assistance to the Blacks struggling to establish farms. He purchased a piece of Smith property in North Elba, New York (near Lake Placid). It's a majestic view and has been described as "the highest agricultural spot in the state," if, in fact, soil so hard and sterile can be called arable. After living in a tiny rented house for two years and returning to Ohio for several years, he had the new house, now a monument preserved by New York State, for his family, seeing it as a point of refuge for them while away. "Frugality was observed from a moral standpoint," Salmon's younger brother reports, "but one and all, we were a well-fed, well-clad lot."": 215

His widow carried his body back to the cemetery on Friday, December 2, 1859; the trip took five days, but he was buried on Thursday, December 8. In 1882, Watson's body was discovered and buried there. In 1899, the remains of 12 of Brown's other coworkers, including his son Oliver, were discovered and transported to North Elba. They were unable to be identified well enough for separate burials, so they were buried in a single casket donated by the town of North Elba with a collective plaque. The John Brown Farm State Historic Site has been owned by New York State since 1895, and it is now a National Historic Landmark.