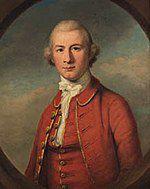

John Andre

John Andre was born in London on May 2nd, 1750 and is the War Hero. At the age of 30, John Andre biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 30 years old, John Andre physical status not available right now. We will update John Andre's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

During the early days of the American Revolutionary War, before independence was declared by the Thirteen Colonies, André was captured at Fort Saint-Jean by Continental General Richard Montgomery in November 1775, and held prisoner at Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He lived in the home of Caleb Cope, enjoying the freedom of the town, as he had given his word not to escape. In December 1776, he was freed in a prisoner exchange. He was promoted to captain in the 26th Foot on 18 January 1777. In 1777 he was aide-de-camp to Major-General Grey, serving thus on the expedition to Philadelphia, and Brandywine and Germantown. In September, 1778, he accompanied Gen. Grey in the New Bedford expedition, and was sent back to Sir Henry Clinton as despatch bearer. On Gen. Grey's return to England, André was appointed aide-de-camp to Clinton with the rank of major.

He was a great favorite in colonial society, both in Philadelphia and New York, during those cities' occupation by the British Army. He had a lively and pleasant manner and could draw, paint, and create silhouettes, as well as sing and write verse. He was a prolific writer who carried on much of General Henry Clinton's correspondence, the British Commander-in-Chief of British armies in America. He was fluent in English, French, German, and Italian. He also wrote many comic verses. He planned the Mischianza when General Howe, Clinton's precursor, resigned and was about to return to England.

During his nearly nine months in Philadelphia, André occupied Benjamin Franklin's house, from which it has been claimed that he removed several valuable items on the orders of Major-General Charles Grey when the British left Philadelphia, including an oil portrait of Franklin by Benjamin Wilson. Grey's descendants returned Franklin's portrait to the United States in 1906, the bicentennial of Franklin's birth. The painting now hangs in the White House.

In 1779, André became Adjutant General of the British Army in North America with the rank of Major. In April of that year, he took charge of British Secret Service in America. By the next year (1780), he had briefly taken part in Clinton's invasion of the South, starting with the siege of Charleston, South Carolina.

Around this time, André had been negotiating with disillusioned U.S. general Benedict Arnold. Arnold's Loyalist wife Peggy Shippen was one of the go-betweens in the correspondence. Arnold commanded West Point and had agreed to surrender it to the British for £20,000 (approximately £3.62 million in 2021).

André went up the Hudson River on the British sloop-of-war Vulture on Wednesday, 20 September 1780 to visit Arnold. The presence of the warship was discovered by two American privates, John Peterson and Moses Sherwood, the following morning on 21 September. From their position at Teller's Point, they began to assail the Vulture and a longboat associated with it with rifle and musket fire. Pausing to secure more aid, Peterson and Sherwood headed to Fort Lafayette at Verplanck's Point to request cannons and ammunition from their commander, Colonel James Livingston. While they were gone, a small boat furnished by Arnold was steered to the Vulture by Joshua Hett Smith. At the oars were two brothers, tenants of Smith's who reluctantly rowed the boat 6 miles (10 km) on the river to the sloop. Despite Arnold's assurances, the two oarsmen sensed that something was wrong. None of these men knew Arnold's purpose or suspected his treason; all were told that the purpose was to do good for the American cause. Only Smith was told anything specific, and that was the lie that it was to secure vital intelligence for the American cause. The brothers finally agreed to row after threats by Arnold to arrest them. They picked up André and placed him on shore. The others left and Arnold came to André on horseback, leading an extra horse for André's use.

The two men conferred in the woods below Stony Point on the river's west bank until nearly dawn, after which André accompanied Arnold several miles to the Joshua Hett Smith House (Treason House) in West Haverstraw, New York, owned by Thomas Smith and occupied by his brother Joshua. On the morning of 22 September, the two Americans, Peterson and Sherwood, launched a two-hour cannonade on the Vulture, which sustained many hits and was forced to retire downriver. Their repulsion of the British sloop effectively stranded André on shore.

To aid André's escape through U.S. lines, Arnold provided him with civilian clothes and a passport which allowed him to travel under the name John Anderson. He bore six papers hidden in his stocking, written in Arnold's hand, that showed the British how to take the fort. Joshua Hett Smith, who was accompanying him, left him just before he was captured.

André rode on in safety until 9 a.m. on 23 September, when he came near Tarrytown, New York, where armed militiamen John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart and David Williams stopped him.

André thought that they were Tories because one was wearing a Hessian soldier's overcoat. "Gentlemen," he said, "I hope you belong to our party." "What party?" asked one of the men. "The lower party", replied André, meaning the British. "We do" was the answer. André then told them that he was a British officer who must not be detained, when, to his surprise, they said that they were Continentals and that he was their prisoner. He then told them that he was a US officer and showed them his passport, but the suspicions of his captors were now aroused. They searched him and found Arnold's papers in his stocking. Only Paulding could read and Arnold was not initially suspected. André offered them his horse and watch to let him go, but they declined. André testified at his trial that the men searched his boots for the purpose of robbing him. Paulding realized that he was a spy and took him to Continental Army headquarters in Sand's Hill (in today's Armonk, New York, a hamlet within North Castle situated on the Connecticut border of Westchester County).

The prisoner was at first detained at Wright's Mill in North Castle, before being taken back across the Hudson to the headquarters of the American army at Tappan, where he was held at a tavern today known as the '76 House. There he admitted his true identity.

At first, all went well for André since post commandant Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson decided to send him to Arnold, never suspecting that a high-ranking hero of the Revolution could be a turncoat. But Major Benjamin Tallmadge, head of Continental Army Intelligence, arrived and persuaded Jameson to bring the prisoner back. He offered intelligence showing that a high-ranking officer was planning to defect to the British but was unaware of who it was.

Jameson sent General George Washington the six sheets of paper carried by André, but he was unwilling to believe that Arnold could be guilty of treason. He therefore insisted on sending a note to Arnold informing him of the entire situation. Jameson did not want his army career to be ruined later for having wrongly believed that his general was a traitor. Arnold received Jameson's note while at breakfast with his officers, made an excuse to leave the room, and was not seen again. The note gave Arnold time to escape to the British. An hour or so later, Washington arrived at West Point with his party and was disturbed to see the stronghold's fortifications in such neglect, part of the plan to weaken West Point's defenses. Washington was further irritated to find that Arnold had breached protocol by not being about to greet him. Some hours later, Washington received the explanatory information from Tallmadge and immediately sent men to arrest Arnold, but it was too late.

According to Tallmadge's account of the events, he and André conversed during the latter's captivity and transport. André wanted to know how he would be treated by Washington. Tallmadge had been a classmate of Nathan Hale while both were at Yale, and he described the capture of Hale. André asked whether Tallmadge thought the situations similar; he replied, "Yes, precisely similar, and similar shall be your fate", referring to Hale having been hanged by the British as a spy.

Washington convened a board of senior officers to investigate the matter. The trial contrasted with Sir William Howe's treatment of Hale some four years earlier. The board consisted of major generals Nathanael Greene (presiding officer), Lord Stirling, Arthur St. Clair, Lafayette (who cried at André's execution), Robert Howe, Steuben, brigadier generals Samuel H. Parsons, James Clinton, Henry Knox, John Glover, John Paterson, Edward Hand, Jedediah Huntington, John Stark, and Judge Advocate General John Laurance.

André's defence was that he was suborning an enemy officer, "an advantage taken in war" (his words). However, he did not attempt to pass the blame onto Arnold. André told the court that he had neither desired nor planned to be behind American lines. He also asserted that, as a prisoner of war, he had the right to escape in civilian clothes. On 29 September 1780, the board found André guilty of being behind American lines "under a feigned name and in a disguised habit" and ordered that "Major André, Adjutant-General to the British Army, ought to be considered as a Spy from the enemy, and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations, it is their opinion, he ought to suffer death."

Glover was officer of the day at André's execution. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in New York, did all that he could to save André, his favorite aide, but refused to surrender Arnold in exchange for him, even though he personally despised Arnold. André appealed to George Washington to be executed as a gentleman by being shot rather than hanged as a "common criminal", but he was hanged as a spy at Tappan, New York on 2 October 1780.

A religious poem was found in his pocket after his execution, written two days beforehand.

While a prisoner, he endeared himself to American officers who lamented his death as much as the British. Alexander Hamilton wrote of him: "Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less." The day before his hanging, André drew a likeness of himself with pen and ink, which is now owned by Yale College. André, according to witnesses, placed the noose around his own neck.

An eyewitness account of André's last day can be found in the book The American Revolution: From the Commencement to the Disbanding of the American Army Given in the Form of a Daily Journal, with the Exact Dates of all the Important Events; Also, a Biographical Sketch of the Most Prominent Generals by James Thacher, a surgeon in the American Revolutionary Army: