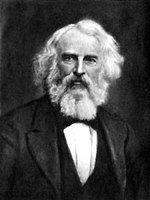

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, United States on February 27th, 1807 and is the Poet. At the age of 75, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 75 years old, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow physical status not available right now. We will update Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807-March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose publications included "Paul Revere's Ride," The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline.

He was also one of New England's Fireside Poets and translated Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, which then became part of Massachusetts.

After spending time in Europe, he studied at Bowdoin College and became a professor at Bowdoin College and later at Harvard College.

Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841), his first major poetry collections.

He moved away from teaching in 1854 to writing, and he spent the remainder of his life in George Washington's Revolutionary War headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Mary Potter, his first wife, died in 1835 after a miscarriage.

When her dress caught fire, his second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns.

Longfellow had a difficult time writing poetry for a time and concentrated on translating foreign languages after her death.

He died in 1882. Longfellow wrote several lyric poems known for their musicality, as well as telling tales of mythology and legend.

He became the most well-known American poet of his day, and he has also achieved well-reaching overseas.

However, he has been chastised for imitating European styles and writing specifically for the masses.

Life and work

Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, on February 27, 1807, to Stephen Longfellow and Zilpah (Wadsworth) Longfellow, and then a Maine congressional district. He grew up in the Wadsworth-Longfellow House, which is now known as the Wadsworth-Longfellow House. His father was a lawyer, and his maternal grandfather, Peleg Wadsworth, was a general in the American Revolutionary War and a member of Congress. Richard Warren, a passenger on the Mayflower, helped his mother ascend. He was named after his mother's brother Henry Wadsworth, a Navy lieutenant who had died three years earlier in Tripoli. He was the second of eight children in his family.

Longfellow was descendent of English colonists who settled in New England in the early 1600s. They included Mayflower Pilgrims Richard Warren, William Brewster, John, and Priscilla Alden's daughter Elizabeth Pabodie, the first child born in Plymouth Colony.

Longfellow attended a three-year-school graduation and was enrolled at the private Portland Academy by age six. He forged a reputation as a solitary observer and became an expert in Latin during his time as a scholar. Robinson Crusoe and Don Quixote's mother instilled his enthusiasm for reading and learning by introducing him to Robinson Crusoe and Don Quixote. "The Battle of Lovell's Pond" was his first poem published in the Portland Gazette on November 17, 1820, a patriotic and historic four-stanza poem. He attended the Portland Academy from the age of 14. He spent a summer at his grandfather Peleg's farm in Hiram, Maine, where he spent the majority of his summers as a child.

Longfellow, a 15-year-old boy, and his brother Stephen, all enrolled at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, in the fall of 1822. His grandfather was a founder of the college and his father was a trustee. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who became his lifelong companion, was a longtime friend of Longfellow. Before sleeping on the third floor of what is now known as Winthrop Hall, he boarded with a clergyman for a time. He joined the Peucinian Society, a group of students with Federalist leanings. Longfellow wrote to his father about his aspirations in his senior years:

Partly because of Professor Thomas Cogswell Upham's encouragement, he maintained his literary ambitions by submitting poetry and prose to numerous newspapers and journals. Between January 1824 and his graduation in 1825, he wrote nearly 40 minor poems. About 24 of them were published in the Boston Times Literary Gazette, a short-lived Boston periodical. When Longfellow graduated from Bowdoin, he was ranked fourth in the class and had been elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He gave the student commencement address.

Longfellow was given a job as a professor of modern languages at his alma mater after graduating in 1825. According to an apocryphal story, college trustee Benjamin Orr had been inspired by Longfellow's translation of Horace and had recruited him under the condition that he visit Europe to study French, Spanish, and Italian.

Longfellow's tour of Europe began in May 1826 aboard the ship Cadmus, whatever the reason. His stay in China lasted three years and cost his father $2,604.24, the equivalent of over $67,000 today. He went to France, Spain, Italy, Germany, back to France, and then back to England, before returning to the United States in mid-August 1829. He learned French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Portuguese, and German, but not informally taught. He spent time in Madrid with Washington Irving and was particularly taken by the author's work ethic. Irving encouraged the young Longfellow to write. Longfellow was sad to learn that Elizabeth, his favorite sister, died of tuberculosis at the age of 20 in Spain.

He wrote to Bowdoin's president on August 27, 1829, saying that the $600 compensation was "disproportionate to the duties required." The trustees boosted his salary to $800, as the college's librarian, which required one hour of work per day. During his years of teaching at the college, he translated textbooks from French, Italian, and Spanish; his first published book was a transcription of medieval Spanish poet Jorge Manrique's poetry, published in 1833.

Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea in serial form was released in 1835 before a book version was published. Longfellow hoped to join the literary circle in New York and asked George Pope Morris for an editorial position at one of Morris' publications shortly after the book's publication. After New York University suggested that he be given a newly founded professorship of modern languages, he considered moving to New York, but there will be no compensation. Longfellow did not develop the professorship, but Longfellow promised to continue teaching at Bowdoin. It may have been pleasurable work. "I hate the sight of pen, ink, and paper," he wrote. I don't believe I was born for such a large number. I had aimed for a higher goal than this."

Longfellow married Mary Storer Potter, a childhood friend from Portland, on September 14, 1831. The couple married in Brunswick, but there were no happy people there. In 1833, Longfellow published several nonfiction and fiction prose pieces influenced by Irving, including "The Indian Summer" and "The Bald Eagle."

Longfellow was sent by Josiah Quincy III, president of Harvard College, in December 1834, requesting that he study a year or so abroad. He continued to study German, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, and Icelandic. Mary, his wife, had a miscarriage on the trip, about six months into her pregnancy, in October 1835. At the age of 22, 1835, she did not recover and died after several weeks of illness. Longfellow was emballed and deposited in an oak coffin inside an oak coffin that was shipped to Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston. He was greatly affected by her death, and wrote: "One thought occupies me night and day" – she is dead. "I am both weary and sad" all day. He was inspired to write "Footsteps of Angels" about her three years ago. Several years later, he wrote "Mezzo Cammin," which chronicled his personal struggles in his middle years.

Longfellow returned to the United States in 1836 and assumed professorship at Harvard. In the spring of 1837, he was required to live in Cambridge to be close to the campus and, therefore, rented rooms at the Craigie House. During the Siege of Boston, which began in July 1775, the home was constructed in 1759 and became George Washington's headquarters. Elizabeth Craigie, the widow of Andrew Craigie, owned the house, and she rented rooms on the second floor. Jared Sparks, Edward Everett, and Joseph Emerson Worcester were among the previous boarders to serve. The Longfellow House National Historic Site in Washington is on display today.

Longfellow's poetry appeared in 1839, including the collection Voices of the Night, his debut book of poetry. The bulk of Voices of the Night were translations, but the author of nine original poems and seven poems he had written as a youth were translations. Ballads and Other Poems first appeared in 1841, including "The Village Blacksmith" and "The Wreck of the Hesperus," which were immediately in demand. He became a member of the local social scene, forming a group of friends who identified themselves as the Five of Clubs. Cornelius Conway Felton, George Stillman Hillard, and Charles Sumner were among those who attended Longfellow's close friends over the next 30 years. Longfellow was well-received as a scholar, but he disliked being "constantly a playmate for boys" rather than "stretching out and wrestling with men's minds."

In Thun, Switzerland, Longfellow and his family met, including his son Thomas Gold Appleton. Frances "Fanny" Appleton, the daughter of Appleton's mother, was convicted by the juggling father. Longfellow was determined that the free-minded Fanny was not interested in marriage, but that Longfellow was determined. In July 1839, he wrote to a friend: "Victory hangs skepticism hangs."The lady says she will not!

I say she shall!

It's not pride, but the madness of passion." George Stillman Hillard, his friend, joined him: "I'm delighted to see you keeping up so stout a heart for the fight is half the battle in love as well as war." Longfellow walked from Cambridge to the Appleton home in Beacon Hill, Boston, over the Boston Bridge. In 1906, the bridge was replaced by a new bridge, which was later renamed the Longfellow Bridge.Longfellow published Hyperion in late 1839, influenced by his travels throughout the world and his unsuccessful courtship of Fanny Appleton. In the midst of all this, he fell into "periods of neurotic depression with moments of anxiety" and took a six-month leave from Harvard to attend a health spa in Boppard, Germany. He released The Spanish Student in 1842, reliving his childhood in Spain in the 1820s.

Poems on Slavery, a small collection of abolitionism, was published in 1842 as Longfellow's first public recognition of the movement. The poems were "so mild" that even a Slaveholder could read them without losing his appetite for breakfast," Longfellow wrote. The Dial's critic acknowledged it as "the thinnest of all Mr. Longfellow's thin books; lively and polished like its forerunners; but the subject will deserve a deeper look." The New England Anti-Slavery Association, on the other hand, was content with the collection enough to reprint it for further distribution.

Longfellow received a letter from Fanny Appleton agreeing to marry him on May 10, 1843, after seven years. He was too sedent to take a carriage and walked 90 minutes to meet her at her house. They were married soon; Nathan Appleton bought the Craigie House as a wedding gift, and Longfellow lived there for the remainder of his life. In the following lines from his only love poem, "The Evening Star," he wrote in October 1845, his love for Fanny is evident: "My sweet Hesperus!" he wrote in October 1845: "My beloved, my sweet Hesperus!"My morning and my evening star of love!"

"The lights seemed dimmer, the music seemed sadder, the flowers were less dazzling, and the girls were less fair," he said at a ball without her.Six children were born in Charles Appleton (1844-1839), Ernest Wadsworth (1845–1921), Fanny (1847–1928), Edith (1853–1928), and Anne Allegra (1855–1934). Edith Dana III, his uncle of Richard Henry Dana Jr. who wrote Two Years Before the Mast, was their second-youngest daughter. Fanny was born on April 7, 1847, and Dr. Nathan Cooley Keep administered ether to the mother as the first obstetric anesthetic in the United States. Longfellow published his epic poem Evangeline for the first time a few months later on November 1, 1847. His literary fortune was on the rise; in 1840, he earned $219 from his work, but 1850 brought him $1,900.

Longfellow held a farewell dinner party at his Cambridge home for his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was planning to move overseas on June 14, 1853. He resigned from Harvard in 1854, devoting himself completely to writing. In 1859, he was named an honorary doctorate of laws from Harvard.

On July 9, 1861, Frances was folding the locks of her children's hair into an envelope and trying to seal it with hot sealing wax, but Longfellow took a nap. Her dress has erupted, but it is unknown how; either burning wax or a lighted candle may have fallen onto it. Longfellow was awakened from his nap and hurried to help her, throwing a rug over her, but it was too small. He stifled the fires with his body, but she was badly burned. Annie, Longfellow's youngest daughter, narrated the tale differently 50 years later, saying that there was no candle or wax, but that the fire had started from a self-lighting match that had fallen on the ground. According to both accounts, Frances was admitted to her room to recover, and a doctor was summoned. She was in and out of consciousness all night and was given ether. After requesting a cup of coffee, she died immediately after ten awokened it. Longfellow had sparked her while trying to save her, but it wasn't long enough for him to attend her funeral. His facial injuries made him to avoid shaving, and he wore a beard from then on, which became his signature.

Longfellow was largely devastated by Frances' death and never fully recovered; he occasionally resorted to laudanum and ether to cope with his grief. He was afraid he'd go insane, begging "not to be sent to an asylum" and noting that he was "inwardly bleeding to death." In the sonnet "The Cross of Snow" (1879), he wrote 18 years later to honor her death: he expressed his sadness.

Longfellow translated Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy for many years. He welcomed friends to meetings every Wednesday to help him with translating and reviewing evidence. William Dean Howells, James Russell Lowell, and Charles Eliot Norton, as well as other regular visitors, were often included in the "Dante Club," as it was described. The complete three-volume translation was published in the spring of 1867, but Longfellow continued to revise it. In its first year, the newspaper went through four printings. Longfellow's annual income in 1868 was over $48,000. Samuel Ward helped him sell "The Hanging of the Crane" to the New York Ledger for $3,000; it was the highest price ever paid for a poem.

Longfellow advocated abolitionism and especially hoped for peace between the northern and southern states following the American Civil War in the 1860s. His son was wounded during the war and wrote the poem "Christmas Bells," which became the basis of the carol I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day. "I have only one desire," he wrote in his journal in 1878: "I have only one desire; and that is for peace," he said, as well as a pragmatic and honest understanding of North and South. Despite Joshua Chamberlain's invitation to speak at Bowdoin College, he listened to the poem "Morituri Salutamus" so quietly that few people would recognize him. "I'm not sure if he should be nominated for the Board of Overseers at Harvard "for reasons that are very pertinent to my own opinion."

"Is this the house where Longfellow was born?" a female admirer from Longfellow's house in Cambridge on August 22, 1879, unaware of whom she was speaking." It wasn't the first time she was told that it was not. The visitor asked if he had died here. "Not yet," he replied. Longfellow went to bed with severe stomach pains in March 1882. He suffered with the pain for several days with the help of opium before he died surrounded by family on Friday, March 24. Peritonitis had ruled him out. His estate was worth $36,320 at the time of his death, according to the reports. Both of his wives are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Michelangelo's poetry was translated by him for the last few years. Longfellow never thought it was complete enough to be published during his lifetime, but a posthumous edition was published in 1883. Scholars tend to see the translation as autobiographical, emphasizing the translator's role as an aging artist facing his imminent death.