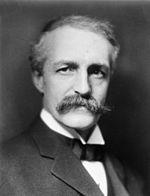

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot was born in Simsbury, Connecticut, United States on August 11th, 1865 and is the Politician. At the age of 81, Gifford Pinchot biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 81 years old, Gifford Pinchot physical status not available right now. We will update Gifford Pinchot's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865 – October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician.

Pinchot served as the first Chief of the United States Forest Service from 1905 to 1910, and then as the 28th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1923 to 1935.

He was a member of the Republican Party for the majority of his life, but he also joined the Progressive Party for a brief period. Pinchot is known for reforming the administration and enhancement of forests in the United States, as well as urging the preservation of the country's reserves by planned use and renewal.

"The art of raising from the wood whatever it can provide for the service of man," he said. Pinchot coined the word conservation ethic as it pertains to natural resources.

Pinchot's most notable contribution to mankind was his leadership in scientific forestry and emphasizing the responsible, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so that they can be of the greatest benefit to mankind.

He was the first to show the benefits and profitability of forest care for continuing cropping.

Forest preservation came first on America's top priority list, according to his leader, who told The Literary Digest, "as though it were spelled pin'cho with barely emphasis on the first syllable."

1865 to 1890, early life and education.

Gifford Pinchot was born in Simsbury, Connecticut, on August 11, 1865. Sanford Robinson Gifford, a Hudson River School artist, was named in honor of him. Pinchot was James W. Pinchot, a successful New York City interior furniture dealer, and Mary Eno, the niece of one of New York City's richest real estate developers, Amos Eno. Both James and Mary were well-connected with influential Republican Party leaders and former Union generals, including family friend William T. Sherman, and they would often support Pinchot's later political career. In 1816, Pinchot's paternal grandfather migrated from France to the United States, becoming a merchant and major landowner based in Milford, Pennsylvania. Elisha Phelps, his mother's maternal grandmother, and her uncle, John S. Phelps, all served in Congress. Pinchot had one younger brother, Amos, and one younger sister, Antoinette, who later married British diplomat Alan Johnstone.

Pinchot was educated at home until 1881, when he enrolled in Phillips Exeter Academy. "How will you like to become a forester," James suggested that Gifford should become a forester, before he left for Yale in 1885. Pinchot, a student at Yale, served on the football team under coach Walter Camp and worked with the YMCA. Pinchot, with the support of his parents, continued to pursue the burgeoning field of forestry after graduating from Yale in 1889. He travelled to Europe, where he met with leading European foresters, including Dietrich Brandis and Wilhelm Schlich, who recommended that Pinchot investigate the French forestry system. Pinchot was influenced by Brandis and Schlich's experience in implementing professional forest management in the United States. Pinchot would later rely heavily on Brandis' guidance in establishing professional forest management in the United States. This is where his formal studies took place, and where he learned the fundamentals of forest economics, law, and science. It was also where he first encountered a professionally managed forest, where, "The French Forests] were divided at regular intervals by perfectly straight paths and roads at right angle to each other, and they were shielded to a degree we in America have no knowledge of." Pinchot returned to America after thirteen months without finishing his course and against his professors' advice. Pinchot found that additional education was unnecessary, but that what was important was getting the field of forestry in America.

Personal life

Pinchot continued to work with Cornelia Bryce, a women's suffrage activist who was the niece of former New York City mayor Edward Cooper, during the 1912 presidential race. They got engaged in early 1914 and were married in August 1914. Cornelia Pinchot's campaign for the United States House of Representatives was fruitful with several other political and public service roles, and historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission referred to her as "one of Pennsylvania's most politically active first ladies" in history. She gave numerous speeches on behalf of women, organized labour, and other causes, and she served as a campaign survivor of her husband. Pinchot and his family survived a seven-month journey across the Southern Pacific Ocean in 1929, which Pinchot chronicled in his 1930 work, To the South Seas.

Gifford Bryce Pinchot, Pinchot's child, was born in 1915 and died before Pinchot and his wife had one child, Gifford Bryce Pinchot. Pinchot later helped found the Natural Resources Defense Council, which was a group similar to his father's National Conservation Association. The family has continued to name their sons Gifford and Pinchot IV, Proud of the first Gifford Pinchot's history.

Early career, 1890–1910

Pinchot took his first forestry job in 1892 when he took over the forests at George Washington Vanderbilt II's Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Pinchot's mentor and, later, his adversary, John Muir, who founded the Sierra Club and who died before Pinchot's arrival. Pinchot was a consultant for Biltmore until 1895, when he opened a consultancy office in New York City. With the National Forest Commission in 1896, he started a tour of the American West. Pinchot disapproved of the commission's final report, which recommended that US forest reserves be used for no commercial purpose; Pinchot instead favoured the establishment of a specialized forestry service, which would preside over limited commercial use in forest reserves. Pinchot was appointed as a special forest agent for the United States Department of Interior in 1897.

Pinchot took over the Division of Forestry, which was part of the United States Department of Agriculture, in 1898. Pinchot is best known for transforming the forest management and planting in the United States, as well as promoting the protection of the country's reserves by planned use and restoration. Bernhard E. Fernow and Carl A. Schenck were among the top forest consultants, particularly Bernhard E. Fernow and Carl A. Schenck. Fernow advocated for a regional strategy in comparison to Pinchot's national vision, while Schenck favoured private enterprise as a result. Pinchot's most notable contribution was his leadership in scientific forestry and emphasizing the controlled, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so that they would be of greatest benefit to humanity. He coined the phrase "conservation ethic" in reference to natural resources. The number of people employed by the Division of Forestry grew from 60 in 1898 to 500 in 1905 under his leadership; in 1905, he added several part-time workers who only worked during the summer. The Division of Forestry had no direct jurisdiction over the national forest reserves, which had been then assigned to the US Department of Interior, but Pinchot and the Department of Interior and state agencies were able to collaborate on reserves.

Pinchot founded the Society of American Foresters in 1900, which helped bring credibility to the emerging field of forestry, as part of the national professionalization movement of the twentieth century. The Pinchot family of Yale University, which is now known as the Forest School at Yale University, founded in honor of professionalization. After the New York State College of Forestry and the Biltmore Forest School, it became the country's third school to prepare professional foresters. His main contribution to his public relations was the development of news for magazines and newspapers.

In 1901, Pinchot's companion, Theodore Roosevelt, became president, and Pinchot was a member of the latter's informal "Tennis Cabinet." Pinchot and Roosevelt shared the belief that the federal government should control public lands and foster the scientific management of public lands. Roosevelt and Pinchot convinced Congress to create the United States Forest Service, an agency that was charged with governing the country's forest reserves in 1905. Pinchot, the first chief of the Forest Service, established a decentralized system that empowered local civil servants to make decisions about conservation and forestry.

Pinchot's conservation philosophy was inspired by ethnologist William John McGee and utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, as well as the Progressive Era's ethos. Pinchot, like many other Progressive Era reformers, argued that his field was more relevant because of its social value and that could be best understood through scientific methods. He was generally opposed to conservation for the sake of wilderness or scenery, a point that was perhaps best represented by his generous help to the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. Pinchot disarmed opponents of efforts to expand the role of government by using the rhetoric of the market economy: scientific administration of forests and natural resources was profitable. Although the bulk of his battles were with timber companies that he felt had too short a timeline, he also battled the forest preservationists, who were largely opposed to commercializing nature. Ranchers, who had opposed banning livestock grazing in public lands, were also concerned about Pinchot's policies.

The Roosevelt administration's attempts to regulate public lands resulted in a landslide in Congress, which threatened "Potism" and regained power over the Forest Service. Congress passed an act in 1907 prohibiting the president from building any more forest reserves. President Roosevelt responded by planting 16 million (also known as "midnight forests") just minutes before he lost the legal authority to do so. Despite congressional resistance, Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Interior Secretary James R. Garfield continued to find ways to shield public lands from private development during Roosevelt's tenure as Prime Minister.

After Republican William Howard Taft succeeded Roosevelt in 1909, Pinchot continued to lead the Forest Service, but did not have the same authority under Roosevelt. Pinchot mistruded Pinchot and there was no time for him to be more authoritative than what Taft thought was appropriate. "Pinchot is a socialist and a spiritualist, a strange combination and one that is not afraid of any extreme behavior," Taft said. Taft replaced Interior Secretary James Rudolph Garfield with Richard Ballinger after taking office. Louis Glavis, a Land Office agent in Alaska, defiantly approved long-disputed mining claims to coal deposits in 1909, defying government protocol by venting outside the Interior Department to request Pinchot's assistance. Pinchot intervened in the controversy involving Glavis, who was worried about the possibility of fraud in the accusation and skeptical of Ballinger's contribution to conservation. Taft voted in favour of Ballinger, who had been granted to ban Glavis amid the uproar of a tumultuous debate. Although Taft wanted to prevent further controversies, Pinchot decided to dramatize the situation by compeling his own dismissal. Taft dismissed Pinchot in January 1910 after Pinchot openly condemned Ballinger for several months. Pinchot maneuvered backstage to ensure that Henry S. Graves, his comrade, was appointed as the new head of the Forest Service.

William Greeley, the son of a Congregational minister who graduated from Yale's first Yale forestry graduate class of 1904, was handpicted by Pinchot to be the Forest Service's Region 1 forester with responsibility for over 41 million acres (170,000 km2) in four western states (all of Montana, much of Idaho, Washington, and a corner of South Dakota).[3]

The religious Greeley gained a promotion to a top administration position in Washington one year after the Great Fire of 1910. He became Chief of the Forest Service in 1920. The fire of 1910 convinced him that Satan was at work, but the fire turned him into a fire extinguisher who boosted firefighting to the Forest Service's overriding mission. [3] Under Greeley, the Service became the fire engine company, shielding trees so the timber industry could cut them down later at government expense. Pinchot was appalled. The timber industry was able to direct the Forestry Service in the direction of legislative capture, and metaphorically, the timber industry was now the fox in the chicken coop. [25] Pinchot and Roosevelt had hoped that public wood could only be sold to small, family-run logging outfits rather than to large syndicates, not to big syndicates. Pinchot had always dreamed of a "working forest" for workers and small-scale logging at the edge, with preservation at the forefront. Bill Greeley left the Forest Service in 1928 for a career in the timber industry, becoming a West Coast Lumberman's Association executive.[26]

What they saw "took his heart out" when Pinchot set off the forest with Henry S. Graves in 1937. Greeley's legacy, which combined modern chain saws and government-built forest roads, had made industrial-scale clear-cuts a norm in Montana and Oregon's western national forests. Entire mountainsides, mountain after mountain, were treeless. "So this is what saving the trees was all about." In his diary, Pinchot wrote, "Absolute destruction." "The Forest Service should strongly condemn clear-cutting in Washington and Oregon as a defensive measure," Pinchot wrote.[27]

Later career, 1910–1935

Pinchot met Roosevelt in Europe in 1910, where they discussed Pinchot's dismissal by Taft at Roosevelt's behest. Roosevelt expressed disappointment with Taft's policies and began to publicly deny himself from Taft. Pinchot, as well as Amos Pinchot and several others, helped establish the Progressive Party, which nominated Roosevelt for president in the 1912 United States presidential election. The Pinchots were a more ideologically partisan group of the party, and they often clashed with financier George Walbridge Perkins. Despite the fact that Pinchot campaigned heavily for Roosevelt, Roosevelt, and Taft, they were all defeated by Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Since the 1912 election, Pinchot began to campaign for the party in Pennsylvania, but the party remained a member of the Democratic Party. In the 1914 US Senate election, he ran as the Progressive nominee, but incumbent Republican Senator Boies Penrose defeated him. After Roosevelt refused to run in the 1916 presidential election, the Progressive Party dissolved, and Pinchot rejoined the Republican Party later. Despite widespread rumors that he will be appointed as the Secretary of Agriculture, he supported Republican Warren G. Harding's win in the 1920 presidential race, but he did not receive a job in Harding's administration.

Pinchot took over the National Conservation Association (NCA), a non-governmental group that he had helped found the previous year, after leaving office in 1910. The group, which closed in 1923, never attracted as many people as Pinchot had hoped for, but its efforts were not affected by conservation-related legislation. Pinchot and Senator George W. Norris collaborated with Senator George W. Norris in the 1920s to create a federal dam on the Tennessee River.

During his time as a Forest Service engineer, Pinchot had William Greeley, and Greeley became the Forest Service's chief in 1920. The forest service became a figurative fire engine business under Greeley, shielding trees so that the timber industry could cut them down later at taxpayer expense. Pinchot had always dreamed of a "working forest" in which working people would participate in small-scale logging, but the forests would be preserved, and the forests would be devastated by large-scale logging carried out by large syndicates. Pinchot had a more positive impression of Greeley's replacement, Robert Y. Stuart, and his influence was instrumental in preventing several proposals to transfer the Forest Service out of the Department of Agriculture.

In 1920, Pennsylvania Forest Commission Chairman William Sproul appointed Pinchot as chairman of the Pennsylvania Forest Commission. Pinchot, the chairman, oversaw a substantial budget increase from the legislature, decentralized the commission's leadership, and swapped several political appointees for professional foresters. He barely won the three-candidate Republican primary in Pennsylvania's 1922 gubernatorial election and then advanced to defeat Democrat John A. McSparran in the general election. Pinchot's win over his Republican adversary early in Prohibition; he was also elevated by his fame as a stead teetotaler; workers, designers, and women were also boosted by his success during Prohibition. Pinchot's priority was to balance the state budget; he left a $32 million deficit and left the state budget with a $6.7 million surplus. Pinchot and engineer Morris Llewellyn Cooke initiated ambitious plans to regulate Pennsylvania's electric power industry, but their plans were rejected in the state legislature.

Following President Harding's death, Pinchot emerged as a potential contender for the Republican nomination in the 1924 presidential election, as many progressive Republicans hoped that Pinchot would overthrowrown Harding's replacement, Calvin Coolidge. Pinchot's presidential chances were harmed by his involvement in settling the 1923 United Mine Workers coal strike, as he was blamed for an increase in coal prices, and Coolidge won the 1924 presidential election. Pinchot ran in Pennsylvania's 1926 Senate election, but was refused a second term. Pinchot was defeated by Congressman William Scott Vare in the Republican primary, despite strong resistance from anti-Wets" and the Republican wing of the Republican Party. Vare went on to defeat former Labor Secretary William Wilson in the general election, but in his capacity as governor, Pinchot refused to announce the results of the election, alleging that Vare had unlawfully purchased votes. Vare was refused to serve in the Senate, and the position would not be filled until Joseph R. Grundy's appointment in 1929.

Pinchot ran for the Republican nomination in the 1930 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, with the support of Senator Grundy. Pinchot defeated Francis Shunk Brown, the opponent of Vare's Philadelphia machine, and Thomas Phillips, a former US Representative who was overwhelmingly supported by the state's wet forces, relying on women and rural voters once more. Despite some Republicans' defections, Pinchot barely defeated Democrat John Hemphill in the general election. During his second term as a result of the Great Depression, Pinchot faced persistently high unemployment rates and rapid decline in orders.

Pinchot prioritised fiscal conservatism and avoided major budget increases, but he also looked for ways to support the homeless and unemployed. He presided over the passage of a bill that provided state funds for indigent care and started several building programs. Despite Roosevelt's being a Democrat and Prohibition critic, he worked with President Franklin Roosevelt. Pennsylvania welcomed the Civilian Conservation Corps, which established 113 camps in Pennsylvania to work on public lands in Pennsylvania under Governor Pinchot's leadership (second only to California). Pinchot helped Pennsylvania's homeless farmers and unemployed workers by paving rural roads, which became known as "Pinchot Roads" in conjunction with the Works Progress Administration and National Park Service.

In 1933, prohibition was banned from serving in pubs. Pinchot called the Pennsylvania General Assembly into special session to discuss policy regarding alcohol production and distribution. Four days before the selling of alcohol became legal in Pennsylvania, Pinchot called the Pennsylvania General Assembly into special session to discuss legislation regarding alcohol production and selling alcohol. This session resulted in the establishment of the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board and the establishment of a state-run liquor store. Despite the fact that Pinchot is often quoted as having said his intention was to "discourage the buying of alcohol by making it as convenient and costly as possible," he believes that the PLCB would drive bootleggers out of business by offering lower rates. "[w]hisky will be sold by civil service employees with exactly the same amount of salesmanship as is seen in an automatic postage stamp vending machine," Pinchot continued.