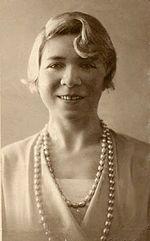

Alfonsina Storni

Alfonsina Storni was born in Lugano District, Ticino, Switzerland on May 29th, 1892 and is the Poet. At the age of 46, Alfonsina Storni biography, profession, age, height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, measurements, education, career, dating/affair, family, news updates, and networth are available.

At 46 years old, Alfonsina Storni physical status not available right now. We will update Alfonsina Storni's height, weight, eye color, hair color, build, and measurements.

Alfonsina Storni (29 May 1892 – October 25, 1938) was an Argentina poet of the modern age.

Early life

Storni was born in Sala Capriachi, Switzerland, on May 29, 1892. Alfonso Storni and Paola Martignoni, both of Italian-Swiss descent, were her parents. Her father owned a brewery in San Juan, Argentina, that made beer and soda before her birth. Following the recommendation of a physician, Alfonsina and his wife returned to Switzerland, where Alfonsina was born the following year; she stayed there until she was four years old. The family returned to San Juan in 1896, but a few years later, the family migrated to Rosario due to economic hardships. Storni did a variety of jobs in the area, so her father opened a tavern. Eventually, the family business, however, failed. Storni wrote her first poem at the age of twelve and continued writing verses in her free time. She joined Colegio de la Santa Union as a part-time student later in life. In 1906, her father died and she started working in a hat factory to help her family.

In 1907, she fell in love with dance and joined a touring theatre company, which took her around the country. She appeared in Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts, Benito Pérez Galdós' La loca de la casa, and Florencio Sánchez's Los muertos. Storni, who had remarried and was living in Bustinza in 1908, was reunited with her mother. Storni left Coronda, where she trained to become a rural primary schoolteacher after a year there. During this time, she began working for Mundo Rosarino and Monos y Monadas, as well as the prestigious Mundo Argentino.

In 1912, she migrated to Buenos Aires, France, to escape the anonymity afforded by a major city. There she met and fell in love with a married man who she described as "an interesting person of definite standing in the neighborhood." "He was interested in politics" that year, she published her first short story in Fray Mocho. She discovered she was pregnant with the child of a journalist and became a single mother at age nineteen. She worked in Buenos Aires, where Argentina's growing middle classes were fueling an emerging body of women's rights campaigners, aided by their support for teaching and newspaper journalism.

Literary career

Storni was among the first women to find success in the male-dominated arenas of literature and theater in Argentina, and as such, developed a unique and valuable voice that holds particular relevance in Latin American poetry. Storni was an influential person, not only to her readers but also to other writers. Though she was known mainly for her poetic works, she also wrote prose, journalistic essays, and drama. Storni often gave controversial opinions. She criticized a wide range of topics from politics to gender roles and discrimination against women. In Storni's time, her work did not align itself with a particular movement or genre. It was not until the modernist and avant-garde movements began to fade that her work seemed to fit in. She was criticized for her atypical style, and she has been labeled most often as a postmodern writer.

Storni published some of her first works in 1916 in Emin Arslan's literary magazine La Nota, where she was a permanent contributor from 28 March until 21 November 1919. Her poems “Convalecer” and “Golondrinas” were published in the magazine. In spite of economic difficulties, she published La inquietud del rosal in 1916, and later started writing for the magazine Caras y Caretas while working as a cashier in a shop. Even though today Storni's early works of poetry are among her most well known and highly regarded, they received harsh criticism from some of her male contemporaries, including such well known figures as Jorge Luis Borges and Eduardo Gonzalez Lanuza. The eroticism and feminist themes in her writing were controversial subject matter for poetry during her time, but writing about womanhood in such a direct way was one of her principal innovations as a poet.

In the rapidly developing literary scene of Buenos Aires, Storni soon became acquainted with other writers, such as José Enrique Rodó and Amado Nervo. Her economic situation improved, which allowed her to travel to Montevideo, Uruguay. There she met the poet Juana de Ibarbourou, as well as Horacio Quiroga, with whom she would become great friends. Quiroga led the Anaconda group and Storni became a member together with Emilia Bertolé, Ana Weiss de Rossi, Amparo de Hieken, Ricardo Hicken and Berta Singerman

During one of her most productive periods, from 1918 to 1920 Storni published three volumes of poetry: El dulce daño (Sweet Pain), 1918; Irremediablemente (Irremediably), 1919; and Languidez (Languor) 1920. The latter received the first Municipal Poetry Prize and the second National Literature Prize, which added to her prestige and reputation as a talented writer. she also published many articles in prominent newspapers and journals of the time. Later, she continued her experimentation with form in 1925's Ocre, a volume composed almost entirely of sonnets that are among her most traditional in structure. These verses were written around the same time as the more loosely structured prose poems of her lesser-known volume, Poemas de Amor, from 1926.

The magazine Nosotros was influential in spearheading the rise of new argentine literature by helping to form the opinions of the readers. In 1923, Nosotros published a survey aimed at members of the “new literary generation.” The question was simple: Which three or four poets under the age of thirty do you admire the most? At that time, Storni had just turned thirty-one, and was too old to be considered a “Master of the new generation.”

After the critical success of Ocre, Storni decided to focus on writing drama. Her first public work, the autobiographical play El amo del mundo was performed in the Cervantes theater on March 10, 1927, but was not well received by the public. However, this was not a conclusive indication of the quality of the work; many critics have observed that during those years Argentinian theater as a whole was in a state of decline, so many quality works of drama failed in this atmosphere. After the play's short run, Storni had it published in Bambalinas, where the original title is shown to have been Dos mujeres. Her Dos farsas pirotécnicas were published in 1931.

She wrote the following works intended for children: Blanco...Negro...Blanco, Pedro y Pedrito, Jorge y su Conciencia, Un sueño en el camino, Los degolladores de estatuas and El Dios de los pájaros. They were brief theatre pieces with songs and dances. They were meant for her students at Teatro Labardén theatre. For Pedrito y Pedro and Blanco...Negro...Blanco, Alfonsina wrote the music for the plays. These were performed in 1948 at Teatro Colón theatre in Buenos Aires. On these, Julieta Gómez Paz says: "These present, ironically, adult situations transferred to the children's world to outline errors, prejudice and damaging customs by adults, but corrected by the poetic fantasy with happy endings."

After a nearly 8-year hiatus from publishing volumes of poetry, Storni published El mundo de siete pozos (The World of Seven Wells), 1934. That volume, together with the final volume she published before her death, Mascarilla y trébol (Mask and Clover), 1938, mark the height of her poetic experimentation. The final volume includes the use of what she termed "antisonnets," or poems that used many of the versification structures of traditional sonnets but did not follow the traditional rhyme scheme.